A Scientific Guide to Filter Selection for Underwater Biofluorescence Imaging in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select and implement optical filters for underwater biofluorescence photography.

A Scientific Guide to Filter Selection for Underwater Biofluorescence Imaging in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select and implement optical filters for underwater biofluorescence photography. It covers the foundational principles of fluorescence excitation and emission, details the components of a standardized imaging system, offers protocols for troubleshooting and image optimization, and outlines validation methods to ensure data reproducibility. By bridging the gap between photographic technique and scientific application, this guide aims to enhance the reliability of fluorescence-based data acquisition for in vivo models and environmental monitoring in aquatic environments.

Principles of Underwater Biofluorescence: From Light Absorption to Scientific Insight

In the study of optical phenomena in nature and their applications in biomedical and environmental research, accurately distinguishing between biofluorescence, bioluminescence, and reflectance is fundamental. While all three involve light interaction with biological materials, their underlying mechanisms and experimental requirements differ significantly. For researchers, particularly those investigating underwater biofluorescence or employing these phenomena in drug development, understanding these distinctions is crucial for proper experimental design, especially in filter selection and imaging protocol development.

Biofluorescence and bioluminescence are often conflated due to their light-emitting properties, yet they represent distinct processes with different biological functions and methodological requirements. Similarly, reflectance imaging, which captures ambient light bouncing off surfaces, requires fundamentally different instrumentation and interpretation. This guide provides detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to differentiate these phenomena, with particular emphasis on filter-based separation techniques essential for accurate data collection in underwater and laboratory settings.

Defining the Core Phenomena

Core Definitions and Distinctions

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Optical Biological Phenomena

| Feature | Biofluorescence | Bioluminescence | Reflectance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | External illumination (blue/UV light) [1] [2] | Internal chemical reaction [1] [3] | Ambient or external white light [2] |

| Energy Mechanism | Absorption and re-emission of light [3] [4] | Chemical energy converted to light [3] [4] | Direct reflection of incident light [2] |

| Emission Duration | Only during excitation illumination [4] | Continues during reaction (no light needed) [1] | Only during illumination [2] |

| Key Requirements | High-energy light source & emission filter [5] [2] | Luciferin substrate & luciferase enzyme [3] [6] | Standard white light source [2] |

| Example Organisms | Corals, scorpions, platypus [3] [5] [7] | Fireflies, anglerfish, glowworms [1] [3] | All non-luminous subjects [2] |

The Molecular and Energetic Basis of Biofluorescence

Biofluorescence occurs when a photon of high energy (short wavelength) from an external source is absorbed by a fluorescent molecule, exciting its electrons. As these electrons return to their ground state, they release energy as a photon of lower energy (longer wavelength). This shift toward longer wavelengths is known as the Stokes Shift [2]. The entire process is instantaneous and ceases immediately when the excitation light source is removed [4].

Key biomolecules include Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), first isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria, and its various mutations that produce cyan, yellow, and red fluorescence [3] [2]. This phenomenon is not a chemical reaction but a physical property of certain pigments and proteins [1].

Diagram 1: The mechanism of biofluorescence at the molecular level, illustrating the Stokes Shift.

Experimental Protocols for Isolation and Imaging

A critical challenge in biofluorescence research is isolating the weak emitted signal from the strong excitation light. This requires a precise optical setup centered on filter selection.

Protocol 1: Isolating and Documenting Biofluorescence

This protocol is adapted for underwater photography but is applicable to laboratory settings.

1. Principle: Use a high-energy blue light source (440-480 nm) to excite fluorescent molecules. Place a barrier filter that blocks the reflected blue light over the detector (camera lens or eye), allowing only the longer-wavelength emitted fluorescence to pass [5] [2].

2. Materials:

- Excitation Light Source: High-power blue LED torch or strobe with a dichroic filter, emitting light at 450-470 nm (Royal Blue/Actinic) [2].

- Barrier Filter: Long-pass (yellow) filter that blocks wavelengths below approximately 480-500 nm [5] [2]. This is placed over the camera lens and/or dive mask.

- Camera System: Capable of manual control and RAW image capture [5].

3. Procedure:

- Setup: Mount the barrier filter securely over the camera lens. In underwater housing, this can be a filter screwed onto the macro port [5].

- Lighting: Illuminate the subject exclusively with the blue excitation light. Ensure no white light contaminates the scene [5].

- Camera Settings: Use manual mode. Start with a fast shutter speed (1/100s - 1/250s) to suppress ambient light, a wide aperture (e.g., f/8) to capture the weak fluorescent signal, and adjust ISO as needed (e.g., 400-800) [5].

- Capture: Compose the shot and capture images in RAW format for post-processing flexibility [5].

- Post-Processing: Enhance contrast, vibrancy, and saturation to compensate for the inherently low-contrast RAW files. Correct white balance if necessary [5].

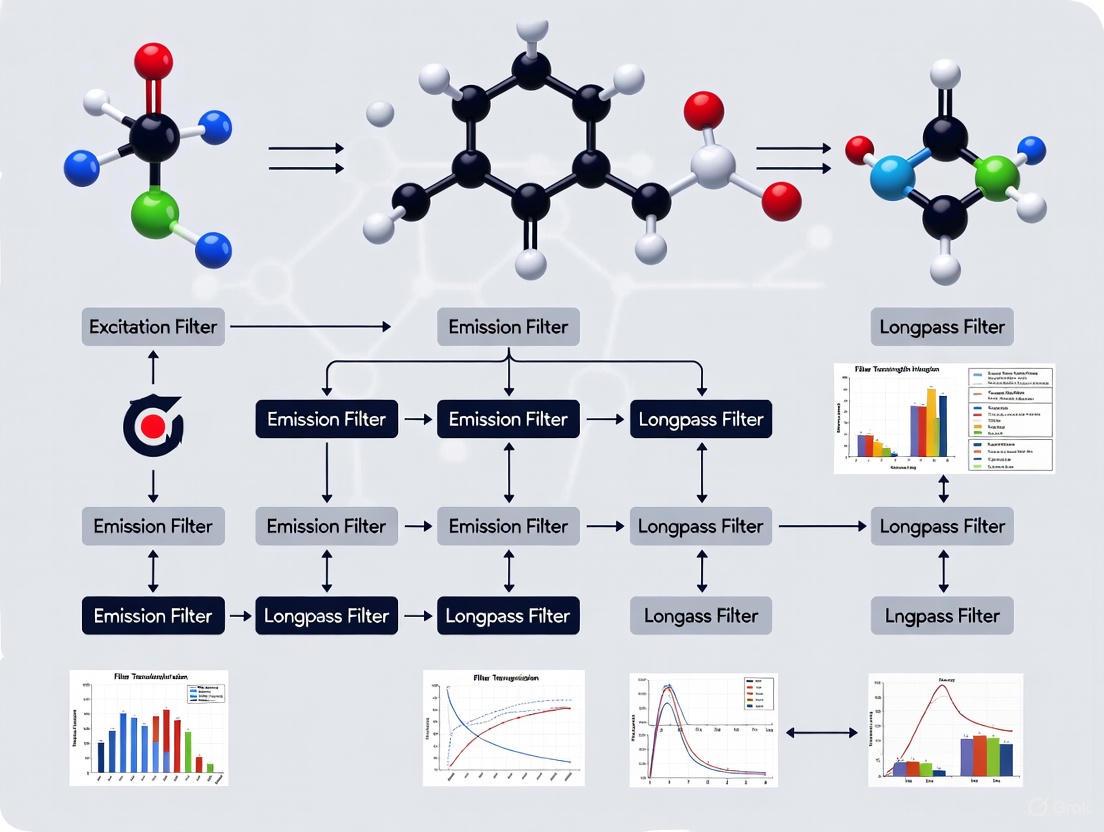

Diagram 2: Optical pathway for biofluorescence imaging, showing the critical role of the barrier filter.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Bioluminescence with a Luminometer

Bioluminescence, being self-emitting, requires no excitation light. Measurement focuses on detecting extremely low light levels from a chemical reaction.

1. Principle: A bioluminescent reaction (e.g., luciferin + O₂ + ATP, catalyzed by luciferase) produces photons. A sensitive detector counts these photons to quantify the reaction rate [1] [6].

2. Materials:

- Luminometer: Instrument containing a light-tight sample chamber and a photomultiplier tube (PMT) or other highly sensitive detector [1].

- Microplate: For holding multiple samples.

- Reagents: Luciferin substrate and appropriate buffers.

3. Procedure:

- Sample Prep: Set up the luminescence reaction in the microplate wells, ensuring cells or tissue express luciferase [6] [8].

- Measurement: Place the microplate into the luminometer's read chamber. The PMT detects light from each well [1].

- Detection & Output: Photons are converted to electrons in the PMT, generating a current proportional to the light intensity. The signal is quantified in Relative Light Units (RLU) [1].

- Data Analysis: For advanced in-vivo applications, Bioluminescence Tomography (BLt) can reconstruct the 3D location and intensity of the light source within an animal [8].

Protocol 3: Differentiating from Reflectance Imaging

Reflectance is the simplest optical phenomenon, involving the direct reflection of incident white light.

Procedure:

- Illuminate the subject with a standard white light source (torch or studio light).

- The subject's surface reflects this light, and the color perceived is determined by the wavelengths it does not absorb.

- Capture the image with a standard camera without any excitation or barrier filters. The recorded colors are a product of the subject's pigmentation and the spectrum of the light source [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Fluorescence and Luminescence Research

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | A naturally occurring biomarker; its gene can be fused to genes of interest to visualize expression and localization in cells and tissues [3] [2]. | Tracking tumor development or specific cell types in transgenic animal models [8]. |

| Blue Light Source & Excitation Filter | Provides the high-energy light required to excite fluorescent molecules. An excitation filter narrows the output to a specific blue/UV wavelength band (e.g., 450-470nm) [5] [2]. | Underwater biofluorescence surveys; laboratory fluorescence microscopy. |

| Barrier (Emission) Filter | Critical optical component that blocks scattered excitation light but transmits the longer-wavelength emitted fluorescence, isolating the signal [5] [2]. | Essential for all biofluorescence imaging protocols to achieve a high signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Luciferin/Luciferase System | The core reagents for bioluminescence. Luciferin is the substrate, and luciferase is the enzyme that catalyzes the light-producing reaction [3] [6]. | Reporter assays in drug development to monitor gene expression, protein-protein interactions, or bacterial load in vivo [8]. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Fluorometer) | Instrument that detects and quantifies fluorescent light emitted by a sample across various wavelengths, generating an emission spectrum [1]. | Precisely identifying the excitation and emission peaks of novel fluorescent proteins. |

| CIELAB Color Space Framework | A standardized color model that allows for the quantitative measurement and comparison of fluorescence color from images, independent of human subjectivity [9]. | Objectively quantifying color variation in fluorescent specimens across studies. |

The precise discrimination between biofluorescence, bioluminescence, and reflectance is not merely academic; it dictates the entire experimental workflow, from equipment selection to data interpretation. For researchers focusing on underwater biofluorescence, the core technical challenge is solved by a specific optical chain: a high-power blue excitation source paired with a precisely selected long-pass barrier filter. In biomedical research, leveraging the unique properties of each phenomenon—whether using GFP for morphological visualization or luciferase for quantitative tracking of disease progression—provides powerful, non-invasive tools for scientific discovery and drug development. A rigorous understanding of these principles ensures the collection of valid, reproducible data in any research context.

The Stokes shift is a fundamental concept in photophysics, defined as the difference in energy or wavelength between the incident light absorbed by a fluorophore and the emitted light it subsequently releases. Named after the 19th-century Irish physicist Sir George Gabriel Stokes, who first observed that fluorescence emission always occurs at longer wavelengths than the excitation light, this phenomenon is critical for enabling sensitive fluorescence detection techniques across numerous scientific fields [10].

In practical terms, the Stokes shift represents the energy loss that occurs during the brief excited-state lifetime of a fluorophore, typically lasting 1-10 nanoseconds [11]. This energy difference fundamentally enables fluorescence detection by allowing researchers to separate emission photons from excitation photons spectrally, thereby facilitating low-background detection of specific signals in complex environments ranging from living cells to underwater ecosystems [11].

This application note examines the photophysical principles underlying the Stokes shift, with particular emphasis on its critical importance for filter selection in underwater biofluorescence photography research. We provide detailed methodologies for quantifying Stokes shifts, optimizing optical configurations, and applying these principles to overcome the unique challenges presented by aquatic environments.

Theoretical Foundations

Jablonski Diagram and Photophysical Processes

The Perrin-Jablonski diagram visually represents the sequential photophysical processes that give rise to fluorescence and the Stokes shift [10] [11]. As shown in Figure 1, this diagram maps the energy states and transitions of a fluorophore during the fluorescence process.

Figure 1. Jablonski Diagram Illustrating the Stokes Shift. The diagram shows (1) excitation to a higher vibrational level, (2) non-radiative relaxation, and (3) fluorescence emission at a longer wavelength [10] [11].

The fluorescence process involves three distinct stages that explain the energy loss mechanism behind the Stokes shift. In Stage 1 (Excitation), a photon of energy (hνEX) is absorbed, promoting the fluorophore to an excited electronic singlet state (S₁') [11]. During Stage 2 (Excited-State Lifetime), the fluorophore undergoes conformational changes and interactions with its molecular environment over 1-10 nanoseconds, dissipating excess energy as heat through vibrational relaxation to reach a relaxed singlet state (S₁) [11]. In Stage 3 (Emission), a photon of lower energy (hνEM) is emitted as the fluorophore returns to its ground state (S₀), with the energy difference between hνEX and hνEM representing the Stokes shift [11].

Molecular Origins of the Stokes Shift

The Stokes shift arises from two primary molecular mechanisms that occur during the excited-state lifetime. Vibrational relaxation involves rapid non-radiative decay from higher vibrational levels of the excited state (S₁, v>0) to its vibrational ground state (S₁, v=0) before emission occurs, as described by the Franck-Condon principle [10]. Solvent reorganization occurs in condensed media where solvent molecules reorient around the more polar excited-state fluorophore during its nanosecond-scale lifetime, further stabilizing the excited state and reducing the energy of emitted photons [12].

The magnitude of the Stokes shift is influenced by the fluorophore's molecular structure and its environment. The Franck-Condon principle dictates that electronic transitions occur without nuclear displacement, making transition probabilities dependent on the overlap integral between vibrational wavefunctions of ground and excited states [10]. Environmental factors including solvent polarity, temperature, pH, and ionic strength can significantly alter the Stokes shift, with more polar solvents typically producing larger shifts due to enhanced stabilization of the excited state [13] [12].

Quantitative Analysis of Stokes Shift

Calculation Methods

The Stokes shift can be quantified using several complementary approaches, each providing different insights into fluorophore behavior. These calculation methods enable researchers to compare fluorophores systematically and select optimal dyes for specific applications.

Table 1: Stokes Shift Quantification Methods

| Method | Formula | Units | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Difference | Δλ = λEM - λEX | Nanometers (nm) | Filter selection, initial characterization |

| Energy Difference | ΔE = hc(1/λEX - 1/λEM) | Electronvolts (eV) | Photophysical studies, quantum yield calculations |

| Wavenumber Difference | Δν̄ = (1/λEX - 1/λEM) | cm⁻¹ | Spectroscopic analysis, solvent effect studies |

For accurate wavenumber calculations, spectra should first be converted to a wavenumber scale before locating maxima, as direct conversion from wavelength maxima can introduce errors due to the spectral bandpass of measurement systems [10]. The magnitude of the Stokes shift has significant practical implications, where large Stokes shifts (>80-120 nm) enable complete separation of excitation and emission bands, thereby facilitating filter selection and improving signal-to-background ratios, while small Stokes shifts (<80 nm) present challenges for filter selection due to significant spectral overlap between excitation and emission bands [13] [14] [15].

Representative Fluorophore Properties

Different fluorophore classes exhibit characteristic Stokes shifts that determine their suitability for various applications, particularly in challenging environments like underwater photography where background signal and light attenuation present significant challenges.

Table 2: Stokes Shift Properties of Common Fluorophore Classes

| Fluorophore Class | Example Dyes | Excitation Maximum (nm) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Stokes Shift (nm) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein derivatives | FITC | 495 | 519 | 24 | Cell labeling, immunoassays |

| Rhodamine derivatives | Rhodamine 6G | 525 | 555 | 30 | Laser dyes, fluorescence microscopy |

| Cyanines | Cy5 | 649 | 670 | 21 | Nucleic acid detection, protein labeling |

| BODIPY | BODIPY FL | 505 | 513 | 8 | Environmental sensing, pH indicators |

| Styrene Oxazolone Dyes | SOD9 | ~520 | ~720 | ~200 | Brain imaging, tumor surgery [15] |

Novel dye development continues to address the need for optimized Stokes shifts in specific applications. Styrene oxazolone dyes (SODs) represent a recent advancement, exhibiting exceptionally large Stokes shifts (136-198 nm) with near-infrared emissions, minimal cross-talk between excitation and emission, and small molecular weights (<450 Da) that facilitate blood-brain barrier penetration for neuroimaging applications [15].

Experimental Protocols

Determining Stokes Shift in Solution

This protocol describes a standardized method for measuring the Stokes shift of fluorophores in solution using a spectrofluorometer, with particular emphasis on addressing the challenges posed by fluorophores with small Stokes shifts.

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Stokes Shift Determination

Item Specification Function Spectrofluorometer Dual-monochromator system Precise wavelength selection & detection Cuvettes Quartz, 1 cm pathlength Housing sample solution with minimal background Buffer solution PBS, pH 7.4 (or appropriate pH) Maintaining physiological conditions Fluorophore stock 1-10 mM in DMSO or water Sample preparation Cutoff filters Various wavelengths (e.g., 515 nm, 530 nm) Reducing scattered light interference [14]

Procedure

Step 1: Sample Preparation Prepare a fluorophore solution in appropriate buffer at an absorbance value of <0.05 at the excitation maximum to avoid inner-filter effects and self-quenching. For most applications, concentrations of 10-100 nM work well for initial characterization [14] [11].

Step 2: Excitation Scan Set the emission monochromator to a literature value or estimated emission maximum (e.g., 540 nm for fluorescein). Perform an excitation scan across a range covering at least 50 nm below to 50 nm above the expected excitation maximum. Identify the excitation maximum (λEXmax) from the resulting spectrum [14].

Step 3: Excitation Wavelength Selection For fluorophores with Stokes shifts <80 nm, set the excitation wavelength to a value lower than λEXmax that provides 90% of maximal relative fluorescence units (RFU) to minimize scattered excitation light interference. This critical step significantly improves signal-to-background ratio for narrow Stokes shift fluorophores [14].

Step 4: Emission Scan with Cutoff Filters With the optimized excitation wavelength, perform emission scans using appropriate cutoff filters (e.g., 515 nm and 530 nm for fluorescein) to block scattered excitation light. Record both sample and blank (buffer only) spectra under identical conditions [14].

Step 5: Data Analysis Identify the emission maximum (λEMmax) from the sample spectrum. Calculate the Stokes shift using Δλ = λEMmax - λEXoptimized. For more accurate results, convert spectra to wavenumber scale before determining maxima [10].

Step 6: Signal-to-Background Optimization Plot signal-to-background ratios (sample RFU/blank RFU) versus emission wavelength for each cutoff filter. Select the emission wavelength and filter combination that provides the highest ratio while maintaining sufficient signal intensity [14].

Workflow for Filter Optimization

The experimental workflow for optimizing filter selection involves sequential steps to maximize signal detection while minimizing background interference, which is particularly crucial for applications with limited signal such as underwater biofluorescence photography.

Figure 2. Filter Optimization Workflow. Decision pathway for selecting optimal excitation (EX) and emission (EM) wavelengths based on Stokes shift characteristics [13] [14].

Application to Underwater Biofluorescence Photography

Technical Considerations for Aquatic Environments

Underwater biofluorescence photography presents unique challenges that necessitate careful consideration of Stokes shift principles and filter selection. The spectral composition of underwater light is dominated by blue wavelengths (440-480 nm) at depths greater than 10 meters, as water efficiently attenuates longer wavelengths, making blue light the most practical excitation source for in situ fluorescence imaging [2].

The optical configuration for underwater biofluorescence imaging requires specialized equipment arranged to maximize fluorescence detection while minimizing background interference. As shown in Figure 3, this involves a blue excitation source, the fluorescing subject, and barrier filters to separate emitted light from excitation light.

Figure 3. Underwater Biofluorescence Imaging Setup. The configuration shows how barrier filters enable visualization of fluorescence by blocking scattered blue excitation light [2].

Optimal Equipment Selection

Excitation sources should emit in the 440-480 nm range (royal blue or actinic light), ideally incorporating dichroic filters to narrow the emission spectrum and improve color saturation in the resulting images [2]. Barrier filters are essential for blocking the intense blue excitation light that would otherwise overwhelm the weaker fluorescence signal; these filters should have cutoff wavelengths just above the blue spectrum (typically >480 nm) while transmitting longer wavelengths where fluorescence emission occurs [2].

The Stokes shift advantage in underwater imaging enables the complete separation of excitation and emission light, which is crucial for detecting weak fluorescence signals against the background of scattered blue light in aquatic environments. This principle allows researchers to document and quantify biofluorescence in marine organisms for census studies, health assessment, and discovery of new species [9] [2].

Protocol for Underwater Biofluorescence Documentation

Equipment Preparation

Configure an underwater camera system with a blue LED torch (440-480 nm) as the excitation source. Install a long-pass barrier filter (e.g., yellow filter with cutoff >500 nm) over the camera lens that corresponds to the expected emission range of the target fluorescence. For scientific quantification, include a color reference standard in the frame to enable post-processing color calibration [9] [2].

Image Acquisition

Position the blue light source at an angle of 20-45° relative to the camera axis to minimize direct backscatter of excitation light. Set camera exposure manually using RAW format, with ISO 400-800, appropriate aperture for depth of field (f/8-16), and shutter speed of 1/60-1/125 s. Maintain a constant distance to subjects across imaging sessions for comparable results [9].

Image Analysis and Quantification

Use color quantization algorithms (K-means clustering in CIELAB color space) to extract dominant color values from fluorescence emissions. Compare images taken under white light and blue excitation to calculate color shifts and quantify fluorescence patterns. Apply consistent white balance adjustments across all images using the reference standard [9].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The strategic selection of fluorophores based on Stokes shift characteristics enables sophisticated applications across biological research and clinical practice. Multiplexed detection of multiple fluorophores simultaneously requires careful selection of dyes with non-overlapping excitation and emission spectra, where large Stokes shifts provide greater flexibility in filter selection and reduce cross-talk between channels [11]. Surgical guidance utilizes fluorophores with large Stokes shifts (e.g., SOD9-TPP) that enable high contrast imaging of tumor margins during resection procedures, with complete separation of excitation and emission bands improving the signal-to-background ratio for precise tissue delineation [15].

Emerging trends in fluorophore development focus on addressing current limitations through innovative chemical design. Novel dye architectures including styrene oxazolone derivatives demonstrate how bioinspiration from fluorescent proteins can yield small molecular dyes with exceptionally large Stokes shifts (>130 nm) and favorable pharmacokinetics for in vivo imaging [15]. Barrier-penetrating probes with optimized Stokes shifts and molecular weights (<450 Da) show enhanced ability to cross biological barriers including the blood-brain barrier, opening new possibilities for neuroimaging and understanding neurological diseases [15].

The Stokes shift represents more than a fundamental photophysical phenomenon—it serves as a critical design parameter for optimizing fluorescence detection across diverse research applications. Through understanding its molecular origins and practical implications, researchers can make informed decisions about fluorophore selection, optical configuration, and detection strategies that maximize signal-to-background ratio in challenging imaging environments.

For underwater biofluorescence photography specifically, the principles outlined in this application note enable researchers to overcome the unique constraints of aquatic environments through strategic filter selection based on the Stokes shift characteristics of target fluorophores. By implementing the standardized protocols for wavelength optimization and image quantification described herein, scientists can generate comparable, quantitative data on marine biofluorescence that advances our understanding of its ecological functions and evolutionary significance.

In fluorescence imaging, whether in a laboratory microscope or in the field of underwater biofluorescence research, the separation of excitation light from emitted fluorescence is a fundamental challenge. This separation is primarily achieved through a critical pair of optical components: the excitation filter and the barrier filter. These filters work in concert to isolate the target signal from overwhelming background noise, enabling the detection of specific fluorescence emissions that would otherwise be invisible to the detector [16]. The precise selection and configuration of these filters directly determine the signal-to-noise ratio, contrast, and overall success of fluorescence detection [17]. In the context of underwater biofluorescence photography, where researchers aim to document and study marine organisms' natural fluorescence, mastering these components is essential for collecting valid, reproducible scientific data.

The Optical System and Component Functions

A standard fluorescence imaging system, from epi-fluorescence microscopes to specialized underwater photography rigs, relies on a core optical arrangement to manage light pathways. This system typically consists of three integrated components: an excitation filter, a dichroic beamsplitter (or dichroic mirror), and an emission filter, collectively known as a filter set or cube [16] [18].

Component Roles and Light Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the functional relationship and light path between these core components within a standard epi-fluorescence imaging system.

Detailed Function of Each Component

Excitation Filter: Positioned between the light source and the sample, the excitation filter functions as a spectral gate. It selectively transmits a specific portion of the light source's broad output, typically a narrow band of shorter wavelengths (e.g., blue light around 450-470 nm for underwater work), to illuminate the sample [16] [17]. This "excitation light" is optimized to match the peak absorption of the target fluorophore.

Dichroic Beamsplitter: This specialized mirror, positioned at a 45-degree angle, acts as a wavelength-specific traffic director. It reflects the shorter-wavelength excitation light downward toward the sample. When the longer-wavelength fluorescence emission returns from the sample, the dichroic's properties allow it to transmit this light through to the detector path [16] [17]. This physical separation of light paths is crucial for efficiency.

Barrier Filter (Emission Filter): This is the final and critical gatekeeper before the detector. Despite the action of the dichroic, a significant amount of scattered excitation light can still travel toward the detector. The barrier filter's primary role is to block this residual excitation light completely while transmitting the desired, longer-wavelength fluorescence emission [19] [16]. Without it, the much brighter excitation light would overwhelm the faint fluorescence signal [19].

Quantitative Filter Characteristics and Selection

Filter Types and Performance Trade-Offs

The two primary filter types used for excitation and emission are bandpass and longpass/edge filters. The choice between them involves a direct trade-off between signal strength and signal isolation.

Table 1: Comparison of Fluorescence Filter Types

| Filter Type | Function | Key Characteristics | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Bandpass [17] | Selects a specific wavelength range from the light source. | Transmits a narrow band, blocking wavelengths outside this band. Maximizes contrast by reducing unwanted background light. | Applications requiring high specificity and minimal background, such as differentiating multiple fluorophores. |

| Excitation Edge Filter [17] | Selects a broad range of shorter wavelengths. | Transmits all wavelengths shorter than a defined "edge" wavelength. Allows more light through than a bandpass filter. | Applications where maximum excitation light intensity is the priority, and spectral isolation is less critical. |

| Emission Bandpass [16] [17] | Isolates a specific portion of the emission spectrum. | Transmits a narrow band centered on the fluorophore's emission peak. Excellent for blocking autofluorescence and residual excitation light. | Multi-labeling experiments and situations where discriminating between multiple emission signals is essential. |

| Emission Longpass [16] [17] | Transmits a broad range of longer wavelengths. | Transmits all wavelengths longer than its cut-on value. Captures the maximum number of fluorescence photons for a brighter signal. | Single-labeling experiments or when detecting all emission above a certain wavelength is acceptable. |

Filter Set Specifications in Microscopy

In formal microscopy, filter sets are carefully balanced. The table below exemplifies this by showing specifications for selected Nikon green excitation filter sets, demonstrating how components are matched for different performance goals.

Table 2: Example Microscope Filter Set Specifications for Green Excitation [20]

| Filter Set | Excitation Filter (nm) | Dichroic Mirror (nm) | Barrier Filter (nm) | Design Purpose & Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-2A | 535/50 (510-560) | 565 (LP) | 590 (LP) | Standard G Set. Wide excitation band for versatility; longpass barrier for bright images. |

| G-2E/C | 540/25 (528-553) | 565 (LP) | 620/60 (590-650) | Narrow Band, Bandpass Barrier. Reduces interference from other fluorophores in multi-labeling. |

| Cy3 HYQ | 545/30 (530-560) | 570 (LP) | 610/75 (573-648) | Medium Band, Bandpass Barrier. Wider bandpass for brighter images with specific fluorophores like Cy3. |

Application in Underwater Biofluorescence Photography

The principles of fluorescence microscopy translate directly to the underwater environment for biofluorescence research. The gear used by researchers and photographers constitutes a field-deployable version of the laboratory fluorescence microscope.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Underwater Fluorescence

A specific set of tools is required to conduct biofluorescence imaging in an underwater environment.

Table 3: Essential Equipment for Underwater Biofluorescence Research

| Research Tool | Function | Equivalent Microscope Component | Research Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Light Source | Provides high-energy photons for excitation, typically in the 440-480 nm "royal blue" or "actinic" range [2]. | Microscope lamp + Excitation Filter | The chosen wavelength must match the absorption peak of the marine GFP-like proteins. LED torches with dichroic filters offer superior saturation [2]. |

| Excitation Filter | A filter placed over a white strobe or flash to convert its output to the required blue light [21]. | Excitation Filter | Using an excitation filter on a powerful strobe is preferred, as it retains sufficient light output despite an ~80% power loss [2]. |

| Barrier Filter | A yellow filter placed over the camera lens or port that blocks reflected blue light, transmitting only the longer-wavelength fluorescence [19] [21]. | Barrier (Emission) Filter | This is non-negotiable; without it, the image is washed out by blue light, and faint fluorescence is invisible [19] [2]. |

| Barrier Filter Mask | A yellow filter over the diver's mask, allowing real-time visual discovery and observation of fluorescing subjects [21] [2]. | Microscope Eyepiece | Enables in-situ behavioral studies and subject location without a camera. Also protects the eyes from prolonged blue light exposure [2]. |

| Macro Lens | Allows close focusing, maximizing the fluorescence signal captured by the camera and filling the frame with small subjects [21]. | Microscope Objective | Essential for studying small marine invertebrates, coral polyps, and other cryptic fluorescing organisms. |

Experimental Protocol: Capturing Biofluorescence Still Imagery

This protocol details the standard methodology for acquiring high-quality still images of biofluorescent marine life for research purposes.

Objective: To record the fluorescence emission of a marine subject with high signal-to-noise ratio and accurate color representation. Materials: Underwater camera housing, macro lens, capable strobe(s), excitation filter(s), lens barrier filter(s), barrier filter mask, blue light torch.

Detailed Procedure:

Gear Preparation: Assemble the camera system and securely attach the excitation filter over the strobe and the yellow barrier filter over the camera lens or housing port. Perform a functional test out of water. Note: The excitation filter will significantly reduce light output, necessitating the use of high strobe power [21] [2].

Subject Discovery: Conduct the dive at night or in very low ambient light. Use the blue light torch in conjunction with the yellow barrier filter mask to scan the reef. Fluorescing subjects will appear as glowing patches against a dark background [21] [2].

Camera Configuration: Adopt settings that maximize light capture to enhance the weak fluorescence signal [21] [22].

- Aperture: Use a relatively open aperture (e.g., f/8 to f/11) to allow more light to reach the sensor while maintaining adequate depth of field [21].

- ISO: Set ISO based on subject fluorescence strength. Corals and anemones are often bright (ISO 400-800), while fish and mobile inverts are dimmer (ISO 1600-3200) [22].

- Shutter Speed: Set to the camera's maximum flash sync speed (e.g., 1/125s or 1/250s) to ensure a dark background free of ambient light [21].

- White Balance: Set a fixed white balance (e.g., 5500K) to ensure consistent color rendition across all images [22].

- Strobe Power: Set strobes to manual mode at high or full power to compensate for the excitation filter [21].

Image Capture and Review: Position the strobes as close to the subject as possible. Compose, focus, and capture the image. Review the histogram and image on the camera display. A successful image will have a dark background with only the fluorescing parts of the subject visible. If there is a blue cast or "bleed," ensure the barrier filter is correctly seated and consider stopping down the aperture slightly [21].

Data Documentation: Record scientific metadata, including species identification (if known), location, depth, water temperature, and time. This contextual data is critical for correlating fluorescence observations with environmental parameters.

Advanced Considerations for Research

Optimizing Signal-to-Noise and Minimizing Photodamage

A core challenge in fluorescence imaging is balancing the need for a clear signal with the risk of photodamage to the specimen. In live-cell microscopy, the main phototoxic effects come from fluorophore photobleaching, which generates free radicals [23]. This is directly applicable to imaging live marine organisms, where minimizing stress is a ethical and scientific imperative. The key is to reduce excitation light exposure by limiting intensity and exposure time to the minimum required to achieve a usable signal-to-noise ratio [23]. In practice, this means using the lowest effective ISO and strobe power that yields a well-exposed fluorescence image.

The Scientific Basis of Marine Biofluorescence

The phenomenon being captured is driven by Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and its homologs. When a high-energy (short-wavelength) photon, typically in the blue spectrum (440-480 nm), strikes a GFP, the protein absorbs the energy. This causes electrons to jump to a higher energy state. Upon instantly decaying back, they emit a lower-energy, longer-wavelength photon [2]. This shift in wavelength is known as the Stokes Shift [2]. The ability of researchers to document this phenomenon reliably hinges on the precise application of the optical filters described in this note.

In underwater biofluorescence photography, excitation filters are paramount for isolating the specific blue light spectrum required to induce fluorescence in marine organisms. These filters selectively transmit a narrow range of wavelengths, typically centered around 450 nm, while blocking other undesirable wavelengths [24]. When this high-energy blue light strikes certain biological subjects, fluorophores within them absorb the light and re-emit it at longer, lower-energy wavelengths, resulting in the stunning glow characteristic of biofluorescence [5]. The precision of the excitation filter directly influences the intensity and clarity of the observed fluorescence, making its selection a critical step in the research methodology [24] [25].

This application note details the selection criteria and experimental protocols for employing excitation filters in underwater biofluorescence research, providing a framework for obtaining consistent, high-quality scientific imagery.

Theoretical Foundations: Spectra vs. Maxima

A fundamental principle in fluorescence work is understanding the distinction between excitation maxima and excitation spectra. While a fluorophore has a peak excitation wavelength (e.g., 488 nm for GFP), it can be excited efficiently across a range of wavelengths, known as its excitation spectrum [25].

The following conceptual diagram illustrates the relationship between a light source's emission, the fluorophore's excitation spectrum, and the resulting emitted fluorescence.

Figure 1: Workflow of an underwater biofluorescence imaging system, showing the role of each optical component.

This spectrum is crucial for selecting an excitation filter. Although a 488 nm source might be most efficient for GFP on a watt-for-watt basis, a powerful 450 nm source is also highly effective, exciting the fluorophore on the "shoulder" of its spectrum [25]. This principle allows for practical filter and light source selection, where a ~450 nm filter can successfully excite a wide range of common marine fluorophores, often emitting in the green, yellow, or red [26].

Selecting the appropriate bandwidth around the 450 nm center wavelength is essential for maximizing signal-to-noise ratio. A broader bandwidth captures more excitation energy but increases the risk of spectral overlap with the emission filter, causing "crosstalk" where excitation light bleeds into the final image [25] [27].

Table 1: Impact of Excitation Bandwidth on Assay Performance

| Excitation Bandwidth | Impact on Signal | Impact on Background & Contrast | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow (10-20 nm) | Lower total light throughput | Minimizes crosstalk; highest contrast [27] | Ideal for bright subjects or when excitation/emission peaks are close |

| Medium (20-40 nm) | Balanced signal strength | Moderate contrast; requires careful filter pairing [27] | General purpose biofluorescence photography |

| Broad (>40 nm) | Highest light throughput | High risk of crosstalk; can reduce contrast [27] | Not recommended for standard biofluorescence work |

For most underwater biofluorescence applications, a bandpass filter with a center wavelength of 450 nm and a bandwidth of 17-20 nm provides an optimal balance, offering strong excitation while maintaining a sufficient spectral gap to isolate the emitted light effectively [28].

Research Reagent Solutions for Underwater Biofluorescence

A rigorous biofluorescence imaging setup requires specific optical components and reagents. The following table details the essential items for a functional system.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Underwater Biofluorescence

| Item | Function/Description | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Blue Excitation Filter | Selects a narrow ~450 nm blue spectrum from the light source to excite fluorophores [26] [24]. | Center Wavelength: 450 nm, Bandwidth: 17-20 nm [28]. |

| High-Power Blue Light Source | Provides the initial high-energy light. Can be a strobe with a fitted filter or a dedicated blue LED video light [26] [5]. | Peak Emission: 450 nm; high irradiance output (e.g., >0.5 W/cm² for clinical platforms) [28]. |

| Yellow Barrier Filter | Blocks reflected blue excitation light and transmits only the longer-wavelength fluorescence (e.g., green, red) to the camera [26] [5]. | Longpass filter with cutoff at 500 nm, or bandpass filter (500-560 nm) [25]. |

| Sensitive Digital Camera | Captures the faint fluorescent emission. Must be able to perform at high ISO settings with low noise [26]. | Full-frame sensor, high ISO (800-4000) capability, shooting in RAW format [5]. |

| Fluorescent Reference Targets | Used for system calibration and focus assistance. Provides a consistent fluorescent signal for setup [29]. | Material with known, stable fluorescence under 450 nm light (e.g., certain plastics or manufactured targets). |

Experimental Protocol: In-Water Biofluorescence Imaging

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for capturing scientifically useful biofluorescence images in an underwater environment.

Equipment Setup and Calibration

- Mount Filters: Attach the blue excitation filters securely over your light sources (strobes or video lights). Thread the yellow barrier filter onto your camera housing's lens port [26].

- Calibrate with Target: Before entering the water, use a fluorescent reference target to check the system. Ensure the excitation light is even and the barrier filter is completely blocking the blue light, leaving only the target's fluorescence visible in the camera's viewfinder.

- Camera Presets: Configure the camera for manual operation. Set to RAW format for maximum post-processing flexibility. A recommended starting point is aperture f/8-f/11, shutter speed 1/160s, and ISO 800-1200 for brightly fluorescing subjects like corals [26].

Field Deployment and Image Acquisition

- Subject Selection: In a low-ambient-light environment (e.g., night dive), scan the reef with a blue video light while looking through your camera or a mask fitted with a yellow barrier filter. Fluorescing subjects will appear to glow [26] [5].

- Focusing: Autofocus may struggle due to low light. Use the focus-assist light from your strobe or a dedicated blue video light. For critical sharpness, switch to manual focus and use the camera's focus peaking feature if available [26].

- Lighting and Composition: Position your lights as close to the subject as possible. Since backscatter does not fluoresce, it is less of an issue than in traditional white-light photography [26]. Compose your shot to minimize distracting non-fluorescent background elements.

- Exposure Adjustment: Take test shots and review the histogram. Adjust settings accordingly:

Data Management and Image Processing

- File Organization: Download and back up all RAW files. Maintain meticulous metadata, including location, subject, and exposure settings.

- Post-Processing: Adjust white balance to correct any color casts from the barrier filter. Increase vibrance and saturation to reflect the true intensity of the fluorescence. Enhance contrast and darken shadows/blacks to clean up the background and make the fluorescence stand out [5]. All adjustments should be applied uniformly across comparable data sets to maintain scientific consistency and avoid post-hoc manipulation [29].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with a correct setup, researchers may encounter challenges. The following flowchart provides a logical pathway for diagnosing and resolving common issues.

Figure 2: A logical troubleshooting workflow for diagnosing common problems in underwater biofluorescence imaging.

The strategic selection and application of a ~450 nm excitation filter is a cornerstone of reproducible underwater biofluorescence research. By understanding the optical principles, utilizing optimized equipment, and adhering to a standardized imaging protocol, researchers can generate high-contrast, quantitative data. This methodology unlocks the potential of biofluorescence as a tool for studying marine biodiversity, organism behavior, and ecological interactions.

In fluorescence imaging, a barrier filter, also known as an emission filter, plays a critical role in isolating the desired fluorescence signal from background noise and reflected excitation light. Positioned in the detection path before the camera or detector, its primary function is to block intense excitation light while transmitting the weaker fluorescence emission from the specimen. In the context of underwater biofluorescence photography, where environmental factors add complexity, proper barrier filter selection becomes paramount for obtaining high-contrast, meaningful data.

Barrier filters are categorized primarily by their spectral transmission properties. Longpass (LP) filters transmit all wavelengths longer than their specified cutoff wavelength, while bandpass (BP) filters transmit only a specific window of wavelengths, blocking both shorter and longer wavelengths [30] [31]. The ubiquitous yellow longpass filter, which typically transmits wavelengths above approximately 500 nm, is a cornerstone for isolating green fluorescence emissions and is the focus of this application note.

Longpass vs. Bandpass Filters: A Comparative Analysis

The choice between a longpass and a bandpass barrier filter involves a fundamental trade-off between signal intensity and specificity. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each filter type.

Table 1: Comparison of Longpass and Bandpass Barrier Filters

| Feature | Longpass (LP) Filter | Bandpass (BP) Filter |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Transmission | Transmits all wavelengths longer than a cutoff point (e.g., ≥500 nm) [30] | Transmits only a specific band (e.g., 500–560 nm) [30] |

| Primary Advantage | Maximizes signal collection by transmitting all longer-wavelength emission [16] | Superior signal-to-noise ratio by blocking unwanted background fluorescence [16] |

| Key Disadvantage | Can transmit ambient red fluorescence or autofluorescence that obscures the target signal [30] | Reduces overall signal brightness; can remove valuable color information [30] |

| Ideal Use Case | Exploratory research, multi-color detection, or when background fluorescence is minimal [30] | Differentiating signals with spectral overlap or when strong, specific background fluorescence is present [30] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting between longpass and bandpass filters in an experimental workflow.

Practical Applications in Biofluorescence Research

The theoretical comparison comes to life in specific research scenarios, which are highly relevant to underwater biofluorescence studies:

Imaging Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) in Plants: When imaging GFP in plants containing chlorophyll (which emits in the far red, ~685 nm), a green bandpass filter (e.g., 500-560 nm) is superior. It blocks the red chlorophyll autofluorescence, making the green GFP signal easy to distinguish. The yellow longpass filter, in contrast, would transmit both the green and red light, potentially masking the GFP signal [30].

Imaging Multiple Fluorophores: In a zebrafish model expressing GFP in the heart and mCherry (red) in blood cells, a yellow longpass filter allows both colors to be viewed and distinguished simultaneously. A green bandpass filter would force both signals to appear in varying intensities of green, eliminating the ability to discriminate based on color [30].

Exploratory Fieldwork: For discovering new fluorescent organisms or compounds in an underwater environment, the longpass filter is definitively recommended. Its broader transmission captures a wider range of potential emission signals that would be blocked by a restrictive bandpass filter [30].

Experimental Protocol for Filter Selection and Use

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for selecting and deploying barrier filters to isolate green fluorescence emission in underwater biofluorescence research.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Underwater Biofluorescence Imaging

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Excitation Light Source | High-power blue light source (e.g., Royal Blue, 440-460 nm) to excite green fluorophores like GFP [25]. |

| Longpass Barrier Filter | Yellow filter (cut-on ~500-510 nm) placed over the camera lens to block scattered blue light and transmit green emission. |

| Bandpass Barrier Filter | Green filter (e.g., 500-560 nm) for comparison or for use in high-background-fluorescence scenarios [30]. |

| Filter Cube (if using microscope) | Holds the matched set of excitation filter, dichroic mirror, and barrier filter [31] [32]. |

| Spectral Data | Excitation and emission spectra for target fluorophores (e.g., from online spectra viewers) [25] [16]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Define the Experimental Goal:

- Determine if the aim is to maximize detected signal, identify multiple unknown fluorophores, or achieve the highest contrast for a specific target signal against a known background.

Gather Spectral Information:

- Obtain the emission spectrum of your target fluorophore (e.g., GFP, which peaks at ~508 nm) [25].

- If possible, identify and obtain the emission spectra of potential sources of background fluorescence (e.g., algal chlorophyll, dissolved organic matter, or coral skeleton autofluorescence).

Select and Mount the Filter:

- Based on the decision matrix in Section 2, mount the appropriate yellow longpass or green bandpass filter securely in front of the camera sensor or in the microscope's filter cube.

Perform Control Imaging:

- Capture a control image without the barrier filter in place under excitation light to visualize the unprocessed signal.

- Capture an image with the barrier filter to isolate the emission.

Analyze and Compare Results:

- Assess image quality based on signal-to-noise ratio and contrast.

- If using a longpass filter and unwanted red/orange fluorescence is present, switch to a bandpass filter and repeat the imaging.

- If using a bandpass filter and the signal is too weak or color information is lost, switch to a longpass filter and repeat.

Advanced Considerations for Underwater Applications

Managing Crosstalk in Multi-Fluorescence Imaging

In experiments involving multiple fluorophores, crosstalk (or bleed-through) is a major concern. Crosstalk occurs when the emission from one fluorophore is detected in the channel intended for another [33]. This can be caused by:

- Emission Crosstalk: Overlap in the emission spectra of different fluorophores [33].

- Excitation Crosstalk: The excitation light for one fluorophore also inadvertently excites another [33].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Filter Selection: Use bandpass filters with narrow transmission windows tailored to the peak emission of each fluorophore to minimize overlap [16].

- Sequential Imaging: Acquire images for each fluorophore separately using its specific excitation/emission filter set, rather than simultaneously with a longpass filter [33].

The Critical Role of the Dichroic Mirror

In a standard epi-fluorescence microscope filter cube, the barrier filter works in concert with an excitation filter and a dichroic mirror (or beamsplitter) [31] [32]. The dichroic mirror reflects the short-wavelength excitation light toward the sample but transmits the longer-wavelength emission light toward the barrier filter and detector [32]. The cutoff wavelength of the dichroic must be carefully chosen to lie between the excitation and emission spectra of the fluorophore for the system to function efficiently.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) and other fluorescent molecules serve as critical biological targets across diverse research domains, from ecological monitoring to biomedical discovery. Reef-building corals represent one of the richest natural repositories of these fluorescent compounds, hosting a remarkable diversity of GFP-like proteins that span the visible spectrum [34]. These fluorescent pigments serve multiple physiological functions, including potential roles in photoprotection, antioxidant activity, and regulation of the coral's internal light environment [35]. The unique spectral properties of coral-derived FPs have enabled their widespread adoption as genetically encoded markers in biomedical research, while simultaneously providing non-invasive indicators of coral health and physiological status for marine ecologists [36].

The expansion of fluorescence-based research has created an urgent need for standardized methodologies to identify, characterize, and utilize these biological targets across experimental systems. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for fluorescence identification in diverse subjects, with particular emphasis on coral ecosystems and emerging in vivo model systems. We integrate technical specifications for imaging hardware, detailed spectral classifications of fluorescent targets, and optimized experimental protocols to facilitate cross-disciplinary research applications. The protocols outlined herein are specifically contextualized within the broader thesis of filter selection for underwater biofluorescence photography, ensuring researchers can extract maximum information from fluorescent biological targets while minimizing environmental impact.

Fluorescent Protein Diversity and Spectral Characteristics

Classification of Coral Fluorescent Proteins

Coral fluorescent proteins are broadly categorized into four main classes based on their spectral emission properties: cyan, green, red, and non-fluorescent chromoproteins [34]. This classification system provides a functional framework for identifying biological targets across species and experimental conditions. Green fluorescence represents the most commonly observed fluorescent phenotype in reef environments, with over half of the approximately 70 known fluorescent pigments falling within the 'greenish' emission spectrum [37]. The diversity of FPs arises from variations in chromophore structure and the protein environment surrounding it, leading to the characteristic emission spectra that enable remote classification of coral taxa and physiological states.

The spectral characteristics of FPs are not randomly distributed across coral phylogeny but rather reflect complex evolutionary patterns including gene duplication, functional divergence, and convergent evolution. Research has identified three major paralogous lineages of coral FPs, with one lineage conserved across all coral families responsible for purple-blue coloration, while the other two lineages have diversified to produce the full spectrum of fluorescent colors (cyan, green, and red) through evolutionary processes [34]. This phylogenetic framework provides valuable context for researchers seeking to identify novel FPs with specific spectral properties for particular applications.

Table 1: Spectral Characteristics of Major Coral Fluorescent Protein Classes

| Color Class | Emission Maxima Range (nm) | Excitation Maxima Range (nm) | Representative Proteins | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyan | 477-495 | 404-450 | psamCFP, mmilCFP | Wide excitation/emission curves (~55 nm width at half-height); some variants with E167 mutation exhibit neutral chromophore ground state |

| Green | >500 | ~490-505 | P-515, P-518 | Narrow spectral curves (~35 nm width at half-height); most common fluorescent color in corals |

| Red | 575-609 | 550-580 | eforCP/RFP | Includes DsRed-type and Kaede-type chromophores with different maturation pathways |

| Chromoproteins | Non-fluorescent | 560-590 | Various pocilloporins | High extinction coefficients but minimal fluorescence; purple-blue visual appearance |

Spectral Library of Fluorescent Biological Targets

A systematic approach to identifying fluorescent biological targets requires comprehensive spectral libraries that capture the diversity of emission signatures across taxa and functional groups. Research conducted across Caribbean reef systems has identified that four primary pigments account for the majority of observed fluorescent colors in cnidarians, designated by their approximate peak emission wavelengths: 486 nm (cyan), 515 nm (green), 575 nm (orange), and 685 nm (red, chlorophyll-a) [35]. These spectral signatures can exist individually or in various combinations within a single organism, creating a complex but classifiable set of fluorescent phenotypes.

Building upon these discrete spectral components, researchers have defined 15 functional groups based on characteristic fluorescence emission spectra measured from Caribbean reef organisms [35]. This classification system enables unsupervised optical classification of benthic habitats and provides a standardized framework for comparing fluorescent targets across studies. The functional groups include corals expressing individual pigments (486-only, 515-only, 575-only), combination phenotypes (486+515, 515+575), and other fluorescent benthic organisms including algae, sponges, and non-photosynthetic fluorescent organisms.

Table 2: Fluorescence-Based Functional Groups for Benthic Classification

| Functional Group | Dominant Pigments | Emission Characteristics | Representative Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coral, 515 only | P-515 | Green emission (~515 nm) | Montastraea annularis, Ricordea florida |

| Coral, 575 only | P-575 | Orange emission (~575 nm) | Various Madracis species |

| Coral, 486+515 | P-486, P-515 | Cyan-green combined emission | Multiple coral families |

| Coral, 515+575 | P-515, P-575 | Green-orange combined emission | Montastraea faveolata |

| Soft coral | Chlorophyll-a | Red emission (~685 nm) | Various octocorals |

| Green algae | Chlorophyll-a | Red emission (~685 nm) | Halimeda, other green algae |

| Coralline sand | - | Broad spectrum | Carbonate sediments |

| Sponge | Phycoerythrin, Chlorophyll-a | Multiple peaks | Various sponge species |

Imaging Systems and Filter Configurations

Underwater Fluorescence Imaging Systems

Specialized imaging systems are required to accurately capture the often-faint fluorescence signals from biological targets in aquatic environments. The Fluorescence Imaging System (FluorIS) represents an optimized platform for wide field-of-view fluorescence imaging of coral reefs, capable of surveying areas up to 50 × 70 cm during both day and night operations [36]. This system addresses key challenges in underwater fluorescence imaging, including limited camera sensitivity, contamination from ambient light, and the need for appropriate spectral separation of fluorescence signals.

The FluorIS incorporates three essential components: (1) an excitation source emitting blue light around 450-470 nm, (2) a camera with enhanced sensitivity to chlorophyll-a fluorescence in the far-red spectrum, and (3) a barrier filter that transmits fluorescence emission while blocking reflected excitation light [36]. A critical innovation in the FluorIS design is the modification of consumer-grade cameras by removing the internal infrared filter, which typically attenuates wavelengths above 650 nm and severely limits detection of chlorophyll-a fluorescence. This modification results in a 20-fold increase in red channel sensitivity compared to unmodified cameras, enabling simultaneous imaging of GFP-like proteins and chlorophyll-a fluorescence [36].

Commercial fluorescence imaging systems such as the Backscatter Fluorescence Filter System provide alternative solutions for researchers requiring standardized, off-the-shelf components. These systems typically include blue excitation filters (emitting around 450 nm) for strobes or video lights and yellow barrier filters for camera lenses and dive masks [26]. The excitation filters convert white strobe light to the blue wavelengths necessary to excite fluorescence, while the barrier filters block this blue light from reaching the camera sensor, isolating the weaker fluorescence signal emitted by the subject [26]. This configuration enables visualization of fluorescence from corals, invertebrates, and certain fish species with minimal equipment modification.

Filter Selection and Spectral Considerations

Optimal filter selection represents a critical determinant of success in fluorescence imaging applications. For coral research, excitation filters should transmit light in the 440-470 nm range to effectively excite the predominant GFP-like proteins, while barrier filters must completely block these wavelengths while transmitting the longer-wavelength fluorescence emissions [26] [36]. The specific filter characteristics should be matched to the experimental objectives: broad-band filters maximize signal intensity for general fluorescence detection, while narrow-band filters enable separation of specific fluorescent proteins in multispectral imaging applications.

For quantitative imaging applications, researchers have demonstrated that a relatively small number of spectral bands (4-8) can achieve high classification accuracy (84-94%) among the 15 fluorescent functional groups when appropriate spectral similarity measures are employed [35]. The Mahalanobis distance metric consistently outperforms other spectral classification methods, particularly when applied to 8 evenly-spaced wavebands across the visible spectrum. This finding has important implications for filter selection in custom imaging systems, suggesting that relatively simple multispectral configurations can support robust classification of fluorescent biological targets.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vivo Oxygen Imaging in Coral Systems

The following protocol details methodology for mapping internal oxygen dynamics in corals using injected sensor nanoparticles, representing an advanced application of fluorescence imaging in live marine organisms [38].

Materials and Reagents

- Oxygen sensor nanoparticles: Composed of platinum(II) tetra(4-fluoro)phenyltetrabenzoporphyrin (PtTPTBPF) immobilized in poly(methyl methacrylate-co-methacrylic acid) (PMMA-MA), 50-70 nm diameter [38]

- Coral specimens: Reef-building coral colonies with intact photosynthetic symbionts

- Injection apparatus: Microneedles or capillary tubes for nanoparticle delivery

- Imaging system: Luminescence lifetime imaging system with fast-gated CCD camera

- Excitation source: High-power LED (617 nm)

- Emission filter: 720 nm long-pass filter combined with bright red plastic filter

- Seawater flow system: Maintains corals under physiological conditions during imaging

Procedure

Nanoparticle Preparation:

- Prepare aqueous dispersion of sensor nanoparticles at concentration ~20 mg/mL

- Characterize particle size distribution via dynamic light scattering (Z-average: 50-70 nm)

- Verify sensor photostability under intense illumination (400-700 nm, ~7000 μmol photons·m⁻²·s⁻¹)

Coral Preparation:

- Acclimate coral colonies to experimental conditions for 24 hours prior to injection

- Ensure continuous seawater flow and appropriate lighting conditions throughout experiment

Nanoparticle Injection:

- Slowly inject 10-50 μL nanoparticle suspension into gastrovascular system using microneedle

- Allow 2-4 hours for nanoparticle dispersion throughout coral tissue

- Monitor distribution via luminescence intensity imaging

Lifetime Imaging:

- Set LED pulse width to 40 μs with appropriate time windows for intensity measurement

- Acquire lifetime image sets with integration times of 40-400 ms

- Maintain constant temperature and flow conditions throughout imaging session

Photosynthetic Stimulation:

- Apply localized light stimuli to activate symbiont photosynthesis

- Record O₂ dynamics during illumination and subsequent dark periods

- Capture images at 10-30 second intervals to resolve O₂ gradient formation

Data Analysis:

- Convert lifetime images to O₂ concentration using predetermined calibration curves

- Quantify O₂ gradients across polyp structures

- Calculate kinetics of O₂ production and consumption

This protocol enables non-invasive mapping of internal O₂ concentration with high spatial and temporal resolution, providing insights into coral metabolic activity and symbiosis function [38]. The use of red-excited, NIR-emitting sensors minimizes interference from tissue autofluorescence and enables deeper tissue penetration compared to UV-blue excited probes.

Protocol: Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting of Coral Cells

This protocol adapts fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for isolation and analysis of specific cell populations from coral tissues, enabling downstream molecular and functional analyses [39].

Materials and Reagents

- Coral specimens: Pocillopora damicornis or other suitable species

- Dissociation media: 3.3× PBS (without Ca and Mg), 2% FCS (vol/vol), 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4

- Cell markers: Fluorescent dyes (see Table 3)

- Filtration system: 40 μm mesh filters

- Flow cytometer: Capable of sorting with multiple laser lines and detection channels

- Cell culture plates: 96-well U-shaped plates for staining

Procedure

Cell Suspension Preparation:

- Scrape soft tissue from coral skeleton with fine blade into petri dish containing staining media

- Mechanically dissociate tissue with fine blade and filter through 40 μm mesh

- Wash cells by centrifugation at 500 × g at 4°C for 5 minutes

- Count cells using hemocytometer with trypan blue viability staining (0.04% final concentration)

Cell Labeling:

- Aliquot 10⁵ cells/well into 96-well U-shaped plates in 50 μL staining media

- Add fluorescent markers at predetermined concentrations (see Table 3)

- Incubate 30 minutes at 20°C

- Wash once with staining media and resuspend in 200 μL containing propidium iodide (5 μg/mL) or DAPI (3 μM) for viability assessment

FACS Analysis and Sorting:

- Set gating parameters based on forward/side scatter and fluorescence controls

- Establish sorting gates for specific cell populations based on marker expression

- Collect sorted populations into appropriate media for downstream applications

- Verify sort purity by reanalysis of collected fractions

Functional Assays:

- Perform phagocytosis assays using fluorescent beads or bacteria

- Conduct gene expression analysis on sorted populations

- Assess metabolic activity using substrate-specific fluorescent probes

Table 3: Fluorescent Cell Markers for Coral Cell Population Analysis

| Compound Name | Fluorescent Indicator | Cellular Target | Concentration | Cell Population Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dihydroethidium | Intracellular superoxide | Oxidative stress | 1 μM | Yes |

| Pyronin Y | dsRNA | RNA content | 0.2 μM | Yes |

| ThioFluor623 | Intracellular thiols | Redox status | 1 μM | Yes |

| Rhodamine Phenylglyoxal | Protein citrullination | Post-translational modification | 0.2 μM | Yes |

| 3-dodecanoyl-NBD Cholesterol | Cholesterol uptake | Membrane dynamics | 1 μM | No |

| MeOSuc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-AMC | Elastase activity | Proteolytic activity | 1 μM | No |

This protocol successfully identifies 12 distinct cellular sub-populations in Pocillopora damicornis using three complementary markers, with verification in the sea anemone Aiptasia pallida demonstrating broader applicability across cnidarian species [39]. The methodology enables isolation of homogeneous cell populations for transcriptional analysis, functional assays, and stress response studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescence Studies in Marine Organisms

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Sensors | PtTPTBPF/PMMA-MA nanoparticles | In vivo O₂ mapping | Red excitation (617 nm), NIR emission (780 nm), suitable for tissue penetration |

| Fluorescent Cell Markers | Dihydroethidium, Pyronin Y, ThioFluor623 | Cell population identification and sorting | Multiple functional assays (ROS, RNA, thiol status) |

| FP Gene Clusters | Octocoral diterpenoid biosynthesis genes | Heterologous production of coral compounds | 5-gene cluster enables lab production of bioactive compounds |

| Excitation Filters | Blue NightSea filters, Backscatter Hybrid Flash filters | Fluorescence excitation | 450 nm transmission, blocks longer wavelengths |

| Barrier Filters | Tiffen #12 yellow, Schott BG39 | Block excitation light, transmit fluorescence | Blocks <500 nm, transmits fluorescence emission |

| Imaging Systems | FluorIS, Backscatter Fluorescence Filter System | Wide-field fluorescence imaging | Modified cameras with IR filter removal for chlorophyll detection |

| Bioactive Compounds | 13-acetoxysarcocrassolide from Lobophytum crassum | Anticancer activity testing | Tubulin polymerization inhibition, apoptosis induction |

Biomedical Applications of Coral-Derived Compounds

The unique biochemical diversity of corals has significant implications for biomedical research and drug development. Soft corals (octocorals) produce complex chemical compounds called diterpenoids that demonstrate potent anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties [40]. Recent research has identified a conserved cluster of five genes responsible for diterpenoid biosynthesis across multiple octocoral species, enabling heterologous production of these compounds in laboratory systems [40]. This genetic breakthrough addresses the critical supply challenge that has previously hampered drug development from marine organisms.

Extracts from the soft coral Lobophytum crassum (LCE) have shown particularly promising bioactivity, demonstrating broad-spectrum inhibition of tubulin polymerization and potent activity against prostate cancer cells [41]. Mechanistic studies reveal that LCE induces apoptosis through increased expression of cleaved caspase-3 and promotes populations of early and late apoptotic cells. In xenograft models, LCE significantly suppresses tumor growth, reducing PC3 tumor volume by 43.9% and Du145 tumor volume by 49.2% [41]. Bioactivity-guided fractionation has identified 13-acetoxysarcocrassolide as the primary active component, exhibiting favorable drug-like properties for further development.

These biomedical applications highlight the importance of fluorescence-based methodologies for identifying and characterizing biologically active corals in their natural habitats. The correlation between fluorescent phenotypes and specific biochemical pathways provides researchers with non-invasive tools to screen for corals of potential biomedical interest, enabling targeted collection that minimizes environmental impact. Furthermore, fluorescence imaging serves as a valuable tool for monitoring coral health in aquaculture facilities established for sustainable drug development [41].

The identification and characterization of fluorescent biological targets from coral ecosystems to in vivo models represents a rapidly advancing field with significant implications for both basic research and applied biotechnology. The integrated methodologies presented in this application note provide researchers with standardized approaches for fluorescence imaging, cell sorting, and metabolic monitoring across experimental systems. Critically, the optimal identification of fluorescent subjects depends on appropriate filter selection matched to the specific spectral properties of target fluorophores, whether for ecological monitoring, physiological assessment, or drug discovery applications.

Advances in imaging technology, particularly the development of sensitive, wide-field systems capable of daytime fluorescence imaging, have transformed our ability to study fluorescent biological targets in their natural contexts. Concurrent progress in molecular techniques has enabled detailed characterization of the genetic basis for fluorescence and bioactivity in marine organisms. These complementary approaches continue to reveal new insights into the diversity and function of fluorescent proteins while identifying novel compounds with significant biomedical potential. As these fields continue to converge, fluorescence-based methodologies will play an increasingly important role in bridging ecological observation and biomedical discovery.

Linking Fluorescence to Physiological Status in Marine Bioconstructors

Marine bioconstructors, such as corals and calcareous algae, are fundamental ecosystem engineers that build complex structures supporting immense marine biodiversity [42] [43]. Assessing their health is critical for monitoring reef ecosystems, which are declining worldwide due to global and local stressors [44]. Chlorophyll fluorescence has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive tool for probing the physiological status of these organisms, as it can provide early warning of stress before visible signs, such as bleaching, occur [42] [44]. This protocol details the application of underwater fluorescence photography to link fluorescence signals to the physiological health of marine bioconstructors, with special emphasis on the critical role of optical filter selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential equipment required for conducting underwater biofluorescence research.

Table 1: Essential Research Equipment for Underwater Biofluorescence Studies

| Item | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Filter | Filters light source to emit primarily blue light (~450-470 nm), exciting fluorescent molecules [45] [46]. | Typically a dichroic filter. Acrylic filters are a cost-effective DIY option [47]. Must block UV light if a UV source is used [48]. |

| Barrier Filter | Blocks reflected blue excitation light, allowing only the longer-wavelength fluorescence to reach the camera sensor [45] [46]. | A long-pass yellow filter (e.g., transmitting >500 nm) is standard. Must be fitted to both the camera lens and diver's mask [47] [45]. |

| Underwater Camera System | Captures high-resolution fluorescence imagery. | Capable of manual mode and RAW capture [46]. Requires an underwater housing. A macro lens is ideal for coral polyps [42] [46]. |

| Controlled Light Source | Provides the excitation light. | Blue LED torches or strobes with excitation filters. A focus light with an excitation filter can aid autofocus [47] [46]. |

| Color Reference Chart | Aids in post-processing color correction and standardization. | Should be fluorescent and used in a control shot under the same excitation/barrier filter setup. |

| Photogrammetry Software | Generates 3D models from 2D images for morphological and fluorescence analysis [42]. | Used for quantifying surface area, volume, and polyp count, and for mapping fluorescence onto 3D structure [42]. |

Quantitative Data on Filter Performance

Selecting the correct filters is paramount for obtaining quantitatively reliable data. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for filters relevant to fluorescence imaging.

Table 2: Optical Filter Performance Metrics for Fluorescence Imaging

| Filter Type / Example | Key Performance Metric | Value / Performance Note | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schott KV-418 (Reference) | UV Blocking & Fluorescence | Industry benchmark for low fluorescence and efficient UV blocking; no longer manufactured [48]. | Historical standard; current alternatives must be qualified against its performance. |