Advanced Filter Optimization Strategies to Reduce Spectral Bleed-Through in Biomedical Imaging and Flow Cytometry

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on combating spectral bleed-through, a pervasive challenge in fluorescence-based techniques.

Advanced Filter Optimization Strategies to Reduce Spectral Bleed-Through in Biomedical Imaging and Flow Cytometry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on combating spectral bleed-through, a pervasive challenge in fluorescence-based techniques. It covers the foundational principles of fluorescence filters and the causes of crosstalk, explores advanced methodological solutions including spectral unmixing and novel filter technologies, and offers a practical troubleshooting framework for experimental optimization. The content also addresses the critical validation and comparative analysis required to implement these strategies in sensitive applications like clinical diagnostics and high-parameter cell profiling, providing a holistic approach to achieving clean, quantitative data in multiplexed experiments.

Understanding Spectral Bleed-Through: Causes, Artifacts, and Impact on Data Fidelity

This guide provides a technical overview of spectral bleed-through, a common artifact in fluorescence microscopy that can compromise experimental data. You will learn its causes, how to identify it, and detailed protocols to prevent or correct it in your research.

Definitions and Core Concepts

Spectral bleed-through (also termed crosstalk or crossover) is the erroneous detection of a fluorescent signal in a channel reserved for a different fluorophore [1] [2]. In multi-labeling experiments, this occurs when the emission or excitation light from one dye is detected by the filter set or photomultiplier intended for another dye [1] [3]. This artifact severely affects all image analysis, including co-localization studies and quantitative measurements like FRET and FRAP, and must be addressed to ensure reliable data [1] [2].

The terms bleed-through, crossover, and crosstalk are often used interchangeably in microscopy to describe this signal contamination [1]. However, in specialized contexts, crosstalk can refer to the minimum attenuation level of two filters in series within the filter manufacturing industry [1].

Underlying Mechanisms

Spectral bleed-through arises from two primary mechanisms:

- Excitation Crosstalk: This occurs when the laser line used to excite one fluorophore also, even weakly, excites a second fluorophore in the sample [2]. Because excitation spectra are typically skewed towards shorter (bluer) wavelengths, this often causes "redder" fluorophores to be excited when a "bluer" fluorophore is targeted [1] [2].

- Emission Crosstalk: This happens when the emission spectrum of one fluorophore overlaps with the detection window (filter) of a second fluorophore [1] [2]. The broad, asymmetrical emission profiles of many dyes mean that the "tail" of a green fluorophore's emission can be detected in the red channel [1]. Emission crosstalk typically occurs more severely from a "greener" dye into a "redder" dye's channel [2].

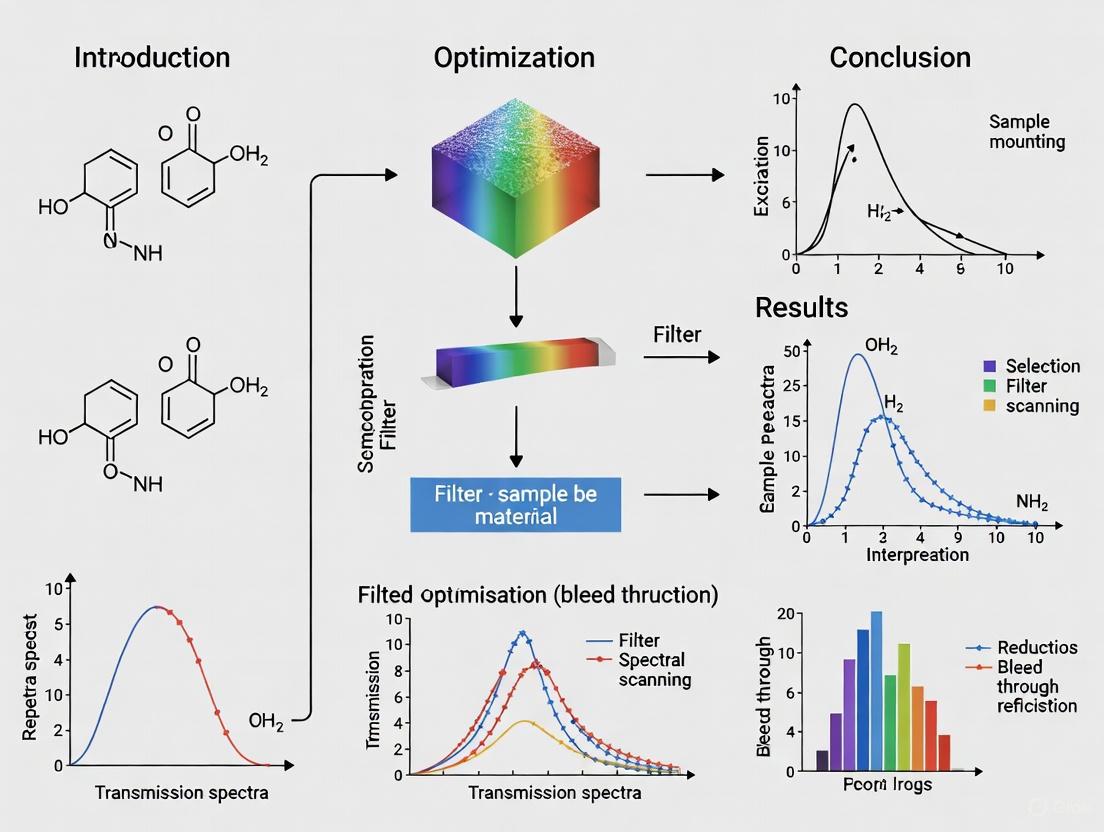

Figure 1: Mechanisms leading to spectral bleed-through.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Spectral Bleed-Through

How do I identify bleed-through in my images?

Perform a single-stain control experiment [4].

- Prepare a sample stained with only the "suspected" fluorophore (e.g., Fluorophore A).

- Acquire images using the same microscope settings you use for your multi-color experiment.

- Collect an image using Fluorophore A's correct channel, then image the same field of view using the channel reserved for your other fluorophore (e.g., Fluorophore B's channel).

- If you detect a signal from the Fluorophore A-only sample in Fluorophore B's channel, you have identified bleed-through [4].

Another detection method uses a 2D intensity histogram plotting the signals of two channels against each other. Bleed-through appears as a distinct 'dark triangle' pattern, indicating a linear relationship where signal in one channel consistently causes a proportional signal in the other [2].

What is the best way to select fluorophores to minimize bleed-through?

Choose fluorophores with well-separated emission spectra [1] [3]. The wider the separation between their peak emission wavelengths, the lower the risk of crosstalk.

- Poor Choice: Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 555. Despite distinct peaks, they have significant spectral overlap, leading to high bleed-through [1].

- Good Choice: Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594. These have reduced spectral overlap and perform well in dual-labeling experiments when probe concentrations are balanced [1].

- Excellent Choice: Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 633. These exhibit virtually no spectral overlap, and bleed-through artifacts should be absent even with high fluorophore concentrations [1].

When planning multi-color experiments, use online tools like fluorescence spectra viewers to evaluate potential dye separation before ordering reagents [4].

My fluorophores are fixed; how can I reduce bleed-through through imaging settings?

If you cannot change your fluorophores, optimize your acquisition settings:

- Use Sequential Scanning: Instead of simultaneously exciting all fluorophores, sequentially scan the specimen with individual laser lines and detect emission for each fluorophore in turn. This prevents excitation crosstalk from the laser line of one dye activating another [1].

- Adjust Detection Bandwidths: Narrow the slit widths or bandpass filters on your detectors to exclude the overlapping "tail" of the emission spectrum from the other dye. Be aware this trades off against collecting less total signal from your target fluorophore [1].

- Image from Red to Blue: Always collect the signal from the fluorophore with the longest (reddest) emission wavelength first, as emission crosstalk typically occurs from bluer dyes into redder channels [1] [2].

Can I correct for bleed-through computationally after image acquisition?

Yes, post-acquisition computational correction is possible if the bleed-through factor is known [5] [2]. This method recalculates the true signal in each channel based on a crosstalk matrix, which defines the fraction of signal from one channel that erroneously appears in another [2].

Application example: This approach is crucial in quantitative super-resolution techniques like FPALM or STORM, where even 2% bleed-through can destroy the ability to measure anti-correlation between species. Correction algorithms can restore accurate correlation values [5]. Specialized software, such as the Huygens Crosstalk Corrector, can detect and apply this correction [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sequential Imaging to Minimize Bleed-Through in Confocal Microscopy

This protocol is adapted from methods used to correct bleed-through between Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 [1].

1. Problem: Simultaneous scanning with 488 nm and 543 nm lasers causes Alexa Fluor 488 signal to bleed into the Cy3 detection channel. 2. Solution: Implement sequential line scanning. - Step 1: Configure the scan settings for "sequential" mode between frames. - Step 2: For the first scan, activate only the 488 nm laser. Set the detection window (e.g., PMT slit) to 500-530 nm. Acquire the image for Alexa Fluor 488. - Step 3: For the next scan, activate only the 543 nm laser. Set the detection window to 555-625 nm. Acquire the image for Cy3. - Step 4: The software will merge the two separately acquired channels. Compare this merged image to one from simultaneous scanning; the sequential image will show a more accurate representation of fluorophore distribution with minimized bleed-through [1].

Protocol: Determining and Applying a Crosstalk Correction Matrix

This grid-based correction method can be applied to multi-color localization microscopy data (e.g., PALM, STORM) and confocal images [5].

1. Determine the Crosstalk Coefficient:

- Image a control sample labeled with only Fluorophore A.

- Measure the mean signal intensity in Channel A (I_AA) and the mean bleed-through signal in Channel B (I_AB).

- The crosstalk coefficient from A to B is calculated as: C_AB = I_AB / I_AA.

- Repeat with a sample labeled with only Fluorophore B to find C_BA [2].

2. Apply the Correction:

- For each pixel in your multi-channel image, the observed signals (O_A, O_B) are a mixture of the true signals (T_A, T_B). This relationship can be expressed with a matrix and solved for the true signals [5] [2]:

Figure 2: Workflow for computational crosstalk correction.

Quantitative Data and Filter Selection

The degree of spectral overlap is a key determinant of bleed-through. The table below summarizes the performance of common Alexa Fluor dye combinations, which can guide your filter optimization research [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Fluorophore Pairs for Dual-Labeling Experiments

| Fluorophore Pair | Emission Peak Separation | Degree of Spectral Overlap | Risk of Bleed-Through | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 555 | Moderate | High | High | Not recommended for quantitative work; use only with careful control of concentrations. |

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 594 | Larger | Moderate | Low | Good for dual-labeling, provided fluorophore concentrations are similar. |

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 633 | Very Large | Negligible | Very Low | Excellent choice; bleed-through is absent even with high concentrations of Alexa Fluor 488. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bleed-Through Management

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor Dye Series | A family of bright, photostable synthetic fluorophores covering a wide spectrum. | Selecting well-separated dyes like Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 633 for minimal overlap [1]. |

| Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibodies | Secondary antibodies processed to minimize cross-reactivity with immunoglobulins from other species. | Reducing non-specific signal and background in multi-color immunofluorescence [4]. |

| TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher | A reagent used to suppress natural autofluorescence in tissue samples, which can mimic bleed-through. | Improving signal-to-noise ratio in tissue sections before imaging to distinguish autofluorescence from specific signal [4]. |

| Antifade Mounting Medium | A mounting medium that retards photobleaching of fluorophores during microscopy. | Preserving fluorescence signal strength, allowing for lower exposure times and gain, which can help mitigate bleed-through [4]. |

| Huygens Crosstalk Corrector Software | Computational tool for detecting and correcting crosstalk in multi-channel images post-acquisition. | Applying a crosstalk matrix to restore accurate signal distribution in images where bleed-through could not be avoided during acquisition [2]. |

FAQ: Spectral Bleed-Through in Multiplex Fluorescence Imaging

What is spectral bleed-through and how does it affect my data?

Spectral bleed-through (also called crossover or crosstalk) occurs when the fluorescence emission from one fluorophore is detected in the channel reserved for another. This artifact complicates data interpretation, particularly in experiments investigating subcellular co-localization or requiring quantitative measurements, such as in FRET or FRAP studies [1]. It can lead to false positives for co-localization, making it appear that two distinct molecules are in the same location when they are not [1] [6].

Which specific fluorophore combinations are most problematic?

The most problematic combinations are those with significant overlap in their emission spectra. The table below summarizes common culprits and suggested alternatives.

| Fluorophore Pair | Type of Overlap | Risk Level | Recommended Alternative(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 555/ Cy3 [1] [7] | Significant emission tail of AF488 spills into AF555/Cy3 detection channel [1] [7]. | High | Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 568 [1]. |

| FITC & TRITC [1] [3] | Broad, overlapping emission spectra; FITC emission detected in TRITC channel [1] [3]. | High | Choose dyes with well-separated spectra (e.g., FITC and Texas Red) [3]. |

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 633/ Alexa Fluor 647 [1] [7] | Virtually no spectral overlap [1] [7]. | Low | This is an ideal combination for colocalization studies [7]. |

| ECFP & EYFP [8] | Highly overlapping emission spectra; significant signal crossover between channels [8]. | High | Use sequential imaging or spectral unmixing [8]. |

What are the best experimental practices to minimize bleed-through?

- Fluorophore Selection: Prioritize fluorophores with well-separated emission spectra and narrow emission peaks [3] [6]. For example, Alexa Fluor 594 is a better partner for Alexa Fluor 488 than Cy3 due to reduced spectral overlap [1].

- Balance Emission Intensities: The brightest and most photostable fluorophores should be reserved for the least abundant cellular targets. Carefully titrate dye concentrations during specimen preparation to prevent a strong signal from overwhelming a weaker one [1] [6].

- Use Control Samples: Always image single-stained control samples. These are crucial for assessing bleed-through and optimizing acquisition parameters [6].

How can I optimize my microscope settings to reduce crosstalk?

- Sequential Scanning: Instead of simultaneous imaging, acquire each channel sequentially by activating only one laser line at a time. This prevents excitation crossover and minimizes emission bleed-through [1] [6].

- Detector Slit/Filter Adjustment: Narrow the detection bandwidth (slit width on confocals or bandpass filters on widefield systems) to capture only the peak emission of the fluorophore and exclude the trailing tails of others [1].

- Acquisition Order: When performing sequential imaging, acquire the signal from the fluorophore with the longest wavelength (reddest) first, then move to shorter wavelengths. This minimizes the chance of exciting bluer dyes with the skewed spectral tails of longer-wavelength lasers [1].

What advanced techniques can separate overlapping fluorophores?

- Spectral Imaging and Linear Unmixing: This technique captures the entire emission spectrum for each pixel in an image. Software algorithms then use reference spectra from control samples to "unmix" the signals and computationally reassign the fluorescence to its correct source fluorophore [8] [6].

- Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM): FLIM can distinguish fluorophores with similar emission spectra but different fluorescence lifetimes (the time a fluorophore spends in the excited state). This provides a separation parameter that is independent of emission wavelength [6].

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Bleed-Through Correction Method Using Sequential Imaging and Control Samples

This protocol provides a detailed methodology to empirically quantify and minimize spectral bleed-through in a double-labeled specimen using a laser scanning confocal microscope.

1. Principle By using single-labeled control samples to determine the degree of signal crossover, acquisition settings can be optimized to minimize bleed-through, or correction factors can be established for post-acquisition analysis [1] [6].

2. Materials and Reagents

- Experimental Sample: Specimen labeled with Fluorophore A and Fluorophore B.

- Control Sample 1: Specimen labeled only with Fluorophore A.

- Control Sample 2: Specimen labeled only with Fluorophore B.

- Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope equipped with at least two independent laser lines and detectors, capable of sequential scanning.

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Image Control Sample 1 (Fluorophore A only).

- Set up the microscope for simultaneous scanning with both Laser A (exciting Fluorophore A) and Laser B (intended for Fluorophore B).

- Using the detector channel for Fluorophore B, acquire an image. The signal detected in this channel represents the bleed-through of Fluorophore A into Fluorophore B's channel [1].

- Note the laser power, detector gain, and any other relevant settings.

Step 2: Image Control Sample 2 (Fluorophore B only).

- Under the same simultaneous scanning settings, use the detector channel for Fluorophore A to image Control Sample 2.

- The signal in this channel represents the bleed-through of Fluorophore B into Fluorophore A's channel. In practice, this is often less severe than the reverse [1].

Step 3: Optimize for Sequential Scanning.

- Configure the microscope for sequential line or frame switching mode.

- For the first channel, activate only Laser A and collect emission with Detector A.

- For the second channel, activate only Laser B and collect emission with Detector B. This physical separation of signals dramatically reduces bleed-through, as demonstrated in Figure 1 of [1].

- Use the control samples to verify that no signal from Fluorophore A appears in the Detector B channel when only Laser A is active, and vice-versa.

Step 4: Image Experimental Sample.

- Apply the optimized sequential scanning settings to acquire the final image of the double-labeled experimental sample.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 | A bright, photostable green-emitting dye. Its emission tail can significantly bleed into yellow and orange channels if not properly controlled [1] [7]. |

| Cy3 | A cyanine dye with orange-red emission. It is often paired with green dyes but suffers from bleed-through from them due to spectral overlap [1]. |

| Rhodamine Derivatives (e.g., TRITC) | Traditional orange-red dyes with very broad emission spectra that often overlap with green dyes like fluorescein [1]. |

| Alexa Fluor 594 | An excellent alternative to Cy3 when pairing with Alexa Fluor 488, as it has better spectral separation, reducing bleed-through [1]. |

| Alexa Fluor 647 | A far-red dye with virtually no spectral overlap with green dyes like Alexa Fluor 488, making it ideal for multicolor experiments [1] [7]. |

| Single-Labeled Control Samples | Specimens prepared with only one fluorophore. They are essential for empirically measuring and correcting for bleed-through artifacts [6]. |

| Quantum Dots | Semiconductor nanocrystals with narrow, symmetric emission spectra, which help minimize spectral overlap in multiplexed imaging [6]. |

Visualizing the Strategy for Managing Spectral Overlap

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for diagnosing and addressing spectral bleed-through in fluorescence imaging.

Methodologies for Signal Separation: From Filter Hardware to Computational Unmixing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Troubleshooting Common LSU Problems

Why do my abundance fractions contain negative values or values greater than 1, and how can I fix this?

Negative values or values exceeding 1 indicate a violation of the linear mixture model's physical constraints. This commonly occurs when the selected endmembers are not pure, are poorly defined, or do not accurately represent the materials present in the scene [9] [10]. To resolve this:

- Review Endmember Purity: Re-examine your training samples or spectral profiles to confirm they represent spectrally pure materials [9].

- Apply Constraints: Use the "Non-negative" Output Value Option in your software. This constraint forces the solution to include only zero or positive abundance values, which is more physically realistic [9].

- Check Data Scaling: If your input image is not reflectance data scaled between 0 and 1 (e.g., 8-bit or 16-bit data), consider normalizing it. Alternatively, check the "Remove continuum" option to normalize the pixel values and input spectral library data to a common baseline [9].

How can I minimize spectral bleed-through or crosstalk in my fluorescence experiments?

Spectral bleed-through is caused by the broad emission profiles of fluorophores overlapping in multiple detection channels [8]. To minimize this:

- Optimize Control Samples: The most critical step is preparing high-quality single-color controls. The positive signal in these controls must be as bright or brighter than in your multi-color sample, and the autofluorescence of the positive and negative controls must be identical [11] [12].

- Use Cells, Not Beads: For biological applications, staining cells typically provides a more accurate spectral signature than compensation beads, as beads may not replicate the spectral properties of fluorophores bound to cellular components [11].

- Leverage Full Spectral Data: Full-spectrum acquisition followed by linear unmixing can distinguish fluorophores with highly overlapping emission spectra more effectively than traditional filter-based methods [12].

What should I do when my classification results are inaccurate due to mixed pixels?

When a single pixel contains multiple materials (e.g., at the boundary between ink and paper, or between different land covers), its spectrum is a mixture, leading to classification errors [13]. A solution is to use spectral unmixing as a preprocessing step:

- Decompose First, Classify Second: Apply linear unmixing to generate abundance maps for each endmember. These maps show the fractional coverage of each material in every pixel.

- Use Reconstructed Spectra: One study found that using the reconstructed spectra from the unmixing process for subsequent classification with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) provided the best overall performance and classification maps [13].

How do I choose between different spectral unmixing algorithms provided by my software?

The choice depends on your data and prior knowledge.

- With Known Endmembers: If you have a spectral library or have identified pure pixels in your image, use a supervised algorithm like Linear Spectral Unmixing to calculate fractional abundances directly [9] [10].

- With Unknown Endmembers: If you do not know the pure materials in advance, use an unsupervised method to find them automatically. The Spectral Hourglass Wizard in ENVI, for example, uses the Pixel Purity Index (PPI) and n-D Visualizer to automatically extract endmembers from the image data itself [14] [10].

- Automated Approaches: Newer tools like SUFI (Spectral Unmixing of Fluorescent Images) automate endmember extraction using Vertex Component Analysis (VCA), reducing manual intervention and user bias [15].

Core Concepts in the Context of Filter Optimization

How does LSU fundamentally differ from traditional filter-based separation?

The following table contrasts the two approaches, highlighting how LSU can be a superior strategy for reducing spectral bleed-through.

Table 1: LSU vs. Traditional Filter-Based Separation

| Feature | Traditional Filter-Based Separation | Linear Spectral Unmixing (LSU) |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Uses narrow bandpass filters to isolate a specific wavelength range from each fluorophore [8]. | Records the full emission spectrum and uses mathematical decomposition to resolve individual signals [8] [12]. |

| Handling Overlap | Prone to bleed-through/crosstalk when emission spectra overlap significantly, as filters cannot perfectly isolate signals [8] [16]. | Designed to handle significant spectral overlap by leveraging the entire spectral "fingerprint" of each fluorophore [12]. |

| Signal-to-Noise | Can suffer from reduced sensitivity because narrow bandpass filters discard a large portion of the emitted photons [8]. | Generally provides better signal-to-noise because it uses the entire emission spectrum for analysis [8]. |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited by the number of available, well-separated filter channels. | Enables higher multiplexing by distinguishing fluorophores with very similar, but not identical, spectral shapes [12]. |

What are the primary causes of unmixing errors, and how do they relate to signal integrity?

Unmixing errors manifest as "swooping" data patterns, asymmetrical negative events, or biologically impossible populations [11]. These errors primarily stem from:

- Inaccurate Reference Spectra: The spectral signature used for unmixing does not match the signature in the multi-color sample. This is often due to using beads instead of cells, poorly gated controls, or differential effects of fixatives on fluorophores [11] [12].

- High Similarity Index: When the spectral shapes of two or more fluorophores are too similar, the algorithm struggles to distinguish them, leading to errors [12].

- Autofluorescence: Native tissue autofluorescence, such as from lipofuscin in brain tissue, adds a complex, mixed background signal that can confound unmixing if not properly accounted for [15].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Workflow for Linear Spectral Unmixing

The diagram below outlines the general workflow for performing linear spectral unmixing, integrating steps from both remote sensing and fluorescence microscopy.

Detailed Protocol: LSU for Hyperspectral Image Analysis

This protocol is adapted for use with software like ArcGIS Pro or ENVI for geospatial or material science applications [9] [14].

Input Data Preparation:

Endmember Selection:

- Method A: Using a Spectral Library. Input an Esri spectral library file (.esl) or an ENVI spectral library file (.sli). The tool will automatically resample the spectra if the number of bands does not match the image [9].

- Method B: Extracting from the Image. Use dimensionality reduction (like MNF transformation) followed by the Pixel Purity Index (PPI) to identify the spectrally purest pixels. Collect these pixels as regions of interest (ROIs) to serve as your endmembers [14] [10].

Execute Linear Spectral Unmixing Tool:

- Set the

in_rasterparameter to your preprocessed image. - Set the

in_spectral_profile_fileto your spectral library or ROI feature class. - Set the

value_optionto"SUM_TO_ONE"and"NON_NEGATIVE"to enforce physical constraints on the abundance fractions [9]. - If dealing with data that has a strong spectral continuum, check the

Remove continuumoption to normalize the data [9].

- Set the

Output and Analysis:

- The tool generates a multiband raster. Each band corresponds to the fractional abundance (from 0 to 1) of one endmember [9].

- Validate the results using ground truth data or by checking the model's residual error to assess the goodness of fit.

Detailed Protocol: LSU for Multispectral Fluorescence Imaging

This protocol is tailored for biological imaging, such as with confocal or spectral flow cytometers [15] [12].

Sample and Control Preparation:

- Stain Samples: Follow your standard immunostaining or hybridization protocol for your multi-color panel [16].

- Prepare Single-Color Controls: For each fluorophore in your panel, prepare a control sample that is stained identically to your full panel but with only that single fluorophore. This is critical for defining an accurate reference spectrum.

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire images of your multi-color sample and all single-color controls using a spectral detector.

- For each pixel, the detector should record the full emission spectrum across a wide wavelength range (e.g., 400-700 nm+) [8].

Spectral Unmixing in Software:

- Load Reference Spectra: Either load the pre-recorded spectra from your single-color controls or use an automated tool like Vertex Component Analysis (VCA) to extract reference spectra directly from your image data [15].

- Perform Unmixing: The software will use a linear least-squares algorithm (e.g., non-negative least squares) to decompose the mixed spectrum at each pixel into the weighted sum of the reference spectra [17].

- Account for Autofluorescence: Include a reference spectrum for tissue autofluorescence (e.g., from an unstained sample) to improve unmixing accuracy [15].

Output:

- The result is a set of "unmixed" images, one for each fluorophore, where the signal in each pixel represents the calculated contribution of that specific fluorophore, free of crosstalk.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Software for Linear Spectral Unmixing Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Library Files | Collections of pure material spectra used as reference endmembers. | Esri (.esl) or ENVI (.sli) files for land-cover classification [9]. |

| Classifier Definition File (.ecd) | A file generated by training a classifier; can be used as input for unmixing in ArcGIS Pro [9]. | Output from the Train Maximum Likelihood Classifier tool. |

| Single-Color Control Samples | Biologically stained samples used to define the pure reference spectrum for each fluorophore. | Critical for accurate unmixing in flow cytometry and microscopy [11] [12]. |

| Pixel Purity Index (PPI) | An algorithm used to find the spectrally purest pixels in an image for endmember selection. | Used in ENVI software during the Spectral Hourglass workflow [14] [10]. |

| Non-Negative Least Squares (NNLS) Solver | The computational algorithm that estimates abundances while enforcing the physical constraint that fractions cannot be negative. | Used in MATLAB's lsqnonneg function and integrated into many commercial software packages [17]. |

| Vertex Component Analysis (VCA) | An automated endmember extraction algorithm that does not require prior knowledge or manual selection. | Used in the SUFI package for fluorescence image analysis [15]. |

| Heparin Blocking Reagent | Used to reduce charge-based, non-specific antibody binding in tissue samples, improving signal-to-noise. | Used in the spectral IBEX protocol for highly multiplexed tissue imaging [16]. |

Technical Diagrams and Data Models

The Linear Mixture Model

The core mathematical principle of LSU is that a mixed spectrum is a linear combination of its pure components. This relationship is visualized below.

Control Optimization Pathway for Accurate Unmixing

The quality of single-color controls is paramount for successful unmixing. This flowchart outlines the optimization process.

Leveraging Fluorescence Lifetime (FLIM) as an Orthogonal Dimension to Spectral Data

Core Concepts and Troubleshooting FAQs

What does it mean that fluorescence lifetime is an "orthogonal" dimension?

Fluorescence lifetime provides information about the molecular environment of a fluorophore that is completely independent of its emission color or intensity. While spectral imaging separates fluorophores based on their emission wavelengths, FLIM distinguishes them based on their characteristic decay rates after excitation. This means two fluorophores with nearly identical emission spectra can be separated if they have different lifetimes, effectively adding a powerful second separation criterion beyond spectral characteristics [6].

How can FLIM specifically help with spectral bleed-through in my multiplexed experiments?

FLIM addresses spectral bleed-through by enabling separation based on decay kinetics rather than just color. When emission from a bright green fluorophore "bleeds through" into your red channel, standard spectral unmixing may fail. However, if the lifetimes of your green and red fluorophores are distinct, FLIM can computationally separate their contributions in the affected pixels, effectively "unmixing" them based on their temporal signatures rather than their spectral profiles [1] [6].

Example Solution: In a experiment with Alexa Fluor 488 (τ ≈ 4.1 ns) and Cy3 (τ ≈ 2.8 ns) showing bleed-through, FLIM analysis can distinguish the Alexa Fluor 488 bleed-through in the Cy3 channel because it maintains its characteristic ~4.1 ns lifetime, allowing accurate quantification of both signals [1].

My FLIM measurements show unexpected lifetime values. What could be causing this?

Unexpected lifetime values typically stem from these common issues:

- Autofluorescence contamination: Cellular autofluorescence typically exhibits short lifetimes (≤ 2 ns) that can distort your sensor measurements [18] [19]

- Low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR): Insufficient photon counts lead to poor lifetime fits [20]

- FRET interactions: Unanticipated energy transfer between fluorophores shortens donor lifetime [18]

- Environmental factors: pH, ion concentration, or temperature changes can alter lifetime [18]

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Acquire a minimum of 1,000 photons per pixel for reliable lifetime determination [21]

- Image an unstained control to characterize autofluorescence lifetime

- Use control samples with single fluorophores to verify expected lifetime values

- Ensure consistent environmental conditions (temperature, pH) during imaging

Can I use FLIM with my existing confocal microscope?

Most modern confocal systems can be adapted for FLIM, but the implementation depends on your specific hardware:

- Time-domain FLIM: Requires pulsed laser sources and time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) electronics [18] [21]

- Frequency-domain FLIM: Uses intensity-modulated lasers and phase-sensitive detection [18] [20]

- Hybrid systems: New "instant FLIM" systems use analog signal processing for faster acquisition [20]

Recommendation: Consult your microscope manufacturer about FLIM upgrades. For initial experiments, consider collaborating with core facilities that already have FLIM-capable systems.

Quantitative Reference Data

Table 1: Fluorescence Lifetime Reference Values for Common Fluorophores

| Fluorophore | Peak Emission (nm) | Lifetime (ns) | Notes & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 | 519 | ~4.1 | Common green dye; sensitive to environment [1] |

| eGFP | 509 | ~2.6-2.8 | Popular fluorescent protein; pH sensitive [18] |

| mCherry | 610 | ~1.4-1.6 | Red fluorescent protein; maturation time ~15 min [22] |

| ATTO 590 | 624 | ~3.5-4.0 | Used in Riboglow-FLIM platform [22] |

| NAD(P)H free | 470 | ~0.4 | Metabolic coenzyme; free vs. bound differs [18] |

| NAD(P)H bound | 470 | 1.0-5.0 | Longer lifetime indicates protein binding [18] |

| FAD | 535 | 2.3-2.9 | Oxidized flavin; metabolic indicator [18] |

Table 2: FLIM Instrumentation Comparison

| Method | Temporal Resolution | Speed | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-domain TCSPC | 5-50 ps | Slow | High precision measurements [21] [23] | Low photon counting rates [21] |

| Frequency-domain | ~100 ps | Fast | Live-cell dynamics [20] | Lower time resolution [18] |

| Instant FLIM | ~250 ps | Very Fast | Real-time imaging [20] | Emerging technology [20] |

| Wide-field TCSPC | 50-100 ps | Medium | Single molecule localization [21] | Specialized cameras required [21] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Implementing FLIM to Resolve Spectral Bleed-Through

Purpose: To separate fluorophores with overlapping emission spectra using fluorescence lifetime contrast.

Materials:

- FLIM-capable microscope system (time or frequency-domain)

- Control samples with individual fluorophores

- Double-labeled test samples

- Immersion oil appropriate for your objective

Procedure:

System Calibration

- Measure instrument response function (IRF) using a known reference standard [21]

- Verify laser pulse characteristics or modulation frequency

- Confirm detector alignment and timing

Control Measurements

- Image single-stained controls for each fluorophore

- Acquire lifetime data with minimum 1,000 photons per pixel [21]

- Determine characteristic lifetime for each fluorophore alone

Test Sample Imaging

- Image double-labeled samples using identical acquisition settings

- Ensure sufficient photon counts for reliable fitting (1,000-10,000 photons/pixel)

- Maintain consistent laser power and detector settings

Data Analysis

- Fit lifetime decays using appropriate model (mono-or bi-exponential)

- Generate lifetime maps and phasor plots

- Apply unmixing algorithms based on predetermined lifetime values

FLIM Spectral Unmixing Workflow

Protocol: Validation with Riboglow-FLIM for Multiplexed RNA Imaging

Purpose: Simultaneously visualize two different RNA species in live mammalian cells using orthogonal lifetime-based tags.

Materials:

- Plasmid constructs: ACTB-Ribo(4A)-590 and ACTB-Ribo(4D)-590 [22]

- Riboglow probe: Cbl-4xGly-ATTO 590 [22]

- Live U-2 OS cells

- FLIM microscope with 590 nm detection capability

Procedure:

Cell Preparation

- Transfert U-2 OS cells with ACTB-Ribo(4A)-590 and ACTB-Ribo(4D)-590 constructs

- Include untransfected controls for background measurement

- Culture for 24-48 hours for expression

Probe Loading

- Prepare Riboglow probe solution (Cbl-4xGly-ATTO 590)

- Load probe into cells via bead loading or gentle permeabilization

- Incubate 30 minutes for binding equilibrium [22]

FLIM Acquisition

- Use 560 nm excitation (or appropriate for your system)

- Collect emission at 590 nm with 20-30 nm bandwidth

- Acquire until >1,000 photons per pixel in regions of interest

- Maintain temperature at 37°C for live-cell imaging

Lifetime Analysis

Expected Results:

- Cells expressing ACTB-Ribo(4A)-590 show intermediate lifetime (~3.2 ns)

- Cells expressing ACTB-Ribo(4D)-590 show longer lifetime (~3.8 ns)

- Untransfected controls show short lifetime (~2.0-2.5 ns) from free probe [22]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FLIM Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Example Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLIM-AKAR [19] | FRET-based kinase activity sensor | PKA signaling dynamics | Double exponential decay; τfree ≠ τbound [19] |

| Riboglow RNA Tags [22] | Genetically encodable RNA labels | Multiplexed RNA visualization | Small tag size; orthogonal A/D variants [22] |

| Cbl-4xGly-ATTO 590 [22] | Fluorescent probe for Riboglow | Live-cell RNA imaging | Lifetime increases upon RNA binding [22] |

| Alexa Fluor Dyes [1] | Bright synthetic fluorophores | General multiplexing | Well-characterized lifetimes; various colors [1] |

| NAD(P)H & FAD [18] | Endogenous metabolic cofactors | Label-free metabolic imaging | Lifetime indicates protein binding state [18] |

| mCherry [22] | Fluorescent protein reference | System validation | Well-characterized τ ≈ 1.4-1.6 ns [22] |

FLIM Separation Principle

A Practical Guide to Optimizing Experiments and Troubleshooting Bleed-Through

For researchers in drug development and biological sciences, achieving clear, multiplexed fluorescence detection is often hampered by spectral bleed-through, a phenomenon where the signal from one fluorophore is detected in the channel of another due to overlapping emission spectra [1]. This artifact complicates data interpretation, especially in co-localization studies and quantitative measurements [1]. Strategic fluorophore selection is the first and most critical line of defense. By carefully balancing intrinsic dye properties—brightness, Stokes shift, and spectral separation—you can design robust experiments that minimize crosstalk and maximize signal fidelity for your filter optimization research.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental properties of a fluorophore that reduce spectral bleed-through?

Spectral bleed-through is influenced by three core, interconnected properties of the fluorophore itself. Optimizing these is crucial for reducing crosstalk.

- Brightness: The brightness of a fluorophore is the product of its extinction coefficient (EC)—its capacity to absorb light—and its fluorescence quantum yield (QY)—the efficiency with which it converts absorbed light into emitted fluorescence [24]. A brighter fluorophore produces a stronger signal for a given concentration, improving the signal-to-noise ratio and making it easier to distinguish from background and overlapping signals.

- Stokes Shift: The Stokes shift is the difference in energy or wavelength between the peak of the absorption (excitation) and the peak of the emission [24] [25]. A larger Stokes shift allows for clearer physical separation of the excitation light from the emission light using optical filters, dramatically reducing background interference and facilitating the detection of emission photons [24].

- Spectral Separation: This refers to selecting fluorophores whose emission spectra are well-spaced, ideally with peaks ≥30–50 nm apart [25]. Minimal spectral overlap is key for multiplexing, as it prevents the emitted light of one dye from being detected in the channel reserved for another, thereby minimizing bleed-through [25] [1].

FAQ 2: How do I strategically select fluorophores to minimize bleed-through in a multiplexed panel?

The goal is to choose a combination of dyes that work in harmony on your instrument while minimizing interference.

- Strategy 1: Prioritize Brightness for Scarce Targets: Match the brightest fluorophores to the antigens or cellular targets with the lowest abundance. This ensures that the weak signal from a low-abundance target is not overwhelmed by bleed-through from a brighter, more abundant one [1].

- Strategy 2: Leverage Large Stokes Shifts: Fluorophores with large Stokes shifts are invaluable as their emission is far removed from their excitation wavelength. This simplifies filter selection by creating a clear gap between the excitation and emission bands, reducing the chance that scattered excitation light will be detected as signal [26].

- Strategy 3: Maximize Spectral Distance: When designing a panel, choose fluorophores with the largest possible gap between their emission peaks. For example, pairing Alexa Fluor 488 with Alexa Fluor 633 results in virtually no spectral overlap, while pairing Alexa Fluor 488 with Alexa Fluor 555 presents a significant bleed-through challenge [1].

- Strategy 4: Balance Fluorophore Intensities: During specimen preparation, carefully balance the concentration or labeling efficiency of your fluorophores so that their emission intensities are similar. If one fluorophore is excessively bright, its emission "tail" can spill over into other detection channels, even if the spectral overlap seems minor [1].

FAQ 3: A dye in my panel is exhibiting unexpected dimming and spectral shift. What could be the cause?

This is a common issue, often linked to the degradation of tandem dyes, which are composed of two covalently bound fluorophores (a donor and an acceptor).

- Root Cause: Tandem dyes can break down over time or due to improper storage or fixation, causing the covalent link between the donor and acceptor molecules to break. This "tandem breakdown" shifts the spectral signature from that of the acceptor (e.g., Cy5.5) back to that of the donor (e.g., PerCP) [27].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Fixative Compatibility: The choice of fixative significantly impacts tandem dye stability. One study found that 0.5% formaldehyde maintained the integrity of all tested biomarkers, while other fixatives led to degradation [27].

- Check Dye Age and Storage: Use fresh dye conjugates and follow storage recommendations. Monitor the stability of your single-color reference controls over time, as their spectral signatures are essential for accurate unmixing in spectral flow cytometry [27].

- Validate with Controls: Always include single-color stained controls in your experiment. If a control sample shows an altered spectral profile, it confirms an issue with the dye conjugate itself [27].

Quantitative Data for Fluorophore Comparison

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Common and Novel Fluorophores

The following table summarizes properties critical for selecting fluorophores to minimize bleed-through.

| Fluorophore | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Stokes Shift (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Relative Brightness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodamine B (Reference) | 553 | 580 | 27 | ~1.06 x 10⁵ [26] | 0.35 [26] | 37,100 |

| YL578 (Novel) | 578 | 634 | 56 | ~0.89 x 10⁵ [26] | 0.74 [26] | 65,860 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 | 495 | 519 | 24 | ~73,000 [24] | High [25] | High |

| Alexa Fluor 647 | 650 | 665 | 15 | ~270,000 [24] | High [25] | High |

| Pacific Blue | 410 | 455 | 45 | N/A | N/A | Medium |

Note: N/A indicates that specific quantitative values were not available in the provided search results. The relative brightness for Rhodamine B and YL578 is calculated as EC × QY [26].

Table 2: Spectral Bleed-Through Potential in Common Dye Pairs

This matrix helps assess the compatibility of different fluorophore combinations for multiplexing.

| Fluorophore Pair | Emission Max Separation | Spectral Overlap | Recommended for Multiplexing? | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 555 | ~36 nm | Moderate to High [1] | Not Recommended | High risk of Alexa Fluor 488 bleed-through into the Alexa Fluor 555 channel. |

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 594 | ~66 nm | Reduced [1] | Good (with balanced labeling) | Viable if the concentration of each probe is similar in the specimen. |

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 633 | ~114 nm | Virtually None [1] | Excellent | Minimal to no bleed-through, even with excessive levels of Alexa Fluor 488. |

| PerCP & PerCP-eFluor 710 | ~35 nm | Significant but unique off-peak signatures [28] | Good (Spectral Flow Cytometry only) | Can be discriminated by their unique full spectral signatures, not just peak emission [28]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Fluorophore Performance and Stability for Long-Term Studies

This protocol is essential for ensuring that your fluorophore-antibody conjugates, especially tandems, remain stable and spectrally pure throughout an experiment.

Methodology:

- Preparation of Single-Color Reference Controls:

- Stain separate aliquots of cells or compensation beads with each individual fluorophore-conjugated antibody used in your panel.

- Fixation: Treat the stained controls with a fixative proven to maintain dye integrity, such as 0.5% formaldehyde, which has demonstrated stability for certain panels for up to five days [27].

- Baseline Acquisition:

- Acquire data from all single-color controls on your flow cytometer or microscope immediately after staining (Day 0). This establishes the reference spectral signature for each fluorophore.

- Stability Tracking:

- Store the fixed single-color controls under defined conditions.

- Re-acquire data at predetermined timepoints (e.g., Day 1, Day 5, Month 1).

- For tandem dyes, calculate the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) ratio of a detector channel specific to the donor fluorophore versus a channel for the tandem peak. An increasing ratio indicates tandem breakdown [27].

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the spectral profiles or MFI from later timepoints to the Day 0 baseline. A significant shift in the emission spectrum or a drop in intensity indicates degradation.

- Validation: Studies show that with the same antibody lot, reference controls can remain effective for unmixing for at least one to two months [27].

Protocol 2: A Multi-View Imaging Approach for Unmixing Highly Overlapping Fluorophores

This advanced microscopy technique leverages both excitation and emission spectra to dramatically improve unmixing accuracy.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Label your biological sample with multiple fluorophores, even those with highly overlapping emission spectra [29].

- Multi-View Image Acquisition:

- Image the same field of view multiple times, each time using a different combination of excitation wavelengths [29].

- Acquire the full emission spectrum for each excitation setting. This generates a complex data cube where each pixel contains information on how the fluorophores respond to different excitations [29].

- Critical Step: Capture images in a descending order of excitation wavelengths (e.g., from longest to shortest) to minimize the impact of photobleaching on the data [29].

- Reference Spectra Collection:

- Prepare reference samples containing each fluorophore alone and image them under the same multiple excitation wavelengths. This allows you to build a complete library of each fluorophore's excitation-emission signature [29].

- Multi-View Linear Unmixing:

- Use a multi-view machine learning algorithm that incorporates the reference spectra from all excitation views. The model uses the distinct excitation profiles of each fluorophore, in addition to their emission profiles, to accurately resolve their individual contributions in the mixed sample [29].

- Validation: This method has been successfully validated on simulated data and real biological samples, such as mixtures of fluorescently labeled Escherichia coli, allowing for the discrimination of fluorophores with extreme spectral overlap [29].

Visual Guide: Strategic Fluorophore Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for selecting fluorophores to minimize spectral bleed-through.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Fluorophore-Based Experiments

This table details essential materials used in fluorescence imaging and flow cytometry experiments.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Antibodies | Enable specific tagging of cellular proteins for detection by flow cytometry or microscopy. The choice of conjugate is critical for panel design. |

| Single-Color Reference Controls | Cells or beads stained with a single fluorophore. They are mandatory for creating a spectral library for unmixing algorithms in spectral flow cytometry or for setting compensation in conventional flow [27]. |

| Cell Viability Dyes | Distinguish live cells from dead cells, which is crucial for accurate immunophenotyping as dead cells can exhibit non-specific antibody binding. |

| Fixation & Stabilization Buffers | Preserve cell morphology and antigen-fluorophore binding after staining. The choice of fixative (e.g., 0.5% vs. 4% formaldehyde) is critical for maintaining the stability of tandem dyes [27]. |

| Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., EGFP, RFP) | Genetically encoded tags for real-time, long-term tracking of protein expression and localization in live cells [28] [25]. |

| Cell Tracking Dyes (e.g., CellTrace) | Fluorescent dyes that stently label cell membranes or cytoplasmic proteins, allowing researchers to monitor cell proliferation, migration, and division over time [28]. |

| Spectral Library (Pre-recorded) | A collection of reference spectral signatures for fluorophores on a specific instrument. This library is used by the unmixing software to deconvolve the signals in a multicolor sample [28] [30]. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges

What is spectral bleed-through and why is it a problem? Spectral bleed-through (also called spectral crosstalk) occurs when the emission signal from one fluorophore is detected in the channel reserved for another fluorophore due to overlapping emission spectra [6]. This can lead to serious errors in data interpretation, such as false co-localization findings or compromised quantitative measurements in techniques like FRET or FRAP [6].

Why is balancing emission intensities crucial in multicolor experiments? If there are significant differences in the emission intensity levels of fluorophores in your sample, the signal from strongly fluorescing species can overwhelm that from weaker species, leading to a disproportionate amount of bleed-through relative to true signal in a particular channel [6]. This imbalance makes it difficult to distinguish actual signal from artifact.

How can I determine if my observed signal is genuine or results from bleed-through? The most reliable method is to prepare and image single-stained control samples for each fluorophore used in your experiment [6]. These controls are crucial for assessing and reducing bleed-through when optimizing image acquisition parameters, and provide reference data that can be used for spectral unmixing.

My sample has strong autofluorescence. What strategies can help? For tissues with strong autofluorescence, such as human nasal polyps, methods like Spectral IBEX (Iterative Bleaching Extends Multiplexity) can be effective [31]. This approach integrates spectral confocal detection with computational unmixing and incorporates heparin blocking to reduce charge-based off-target binding, which improves the signal-to-background ratio and suppresses tissue autofluorescence [31].

Can I fix bleed-through issues after I've already collected my images? Yes, spectral unmixing algorithms can mathematically resolve the signal from each fluorophore after image acquisition [6]. Linear unmixing methods use reference spectra to calculate distribution coefficients for each component fluorophore, while cluster analysis methods determine the main distribution coefficients by fitting when no spectral information is available [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Severe Bleed-Through in Multicolor Imaging

Symptoms:

- Apparent co-localization of signals that should be separate

- High background signal in channels where no fluorophore should be detected

- Inability to distinguish individual signals in overlay images

Solutions:

- Optimize Fluorophore Selection

Balance Emission Intensities Experimentally

Adjust Instrument Configuration

Problem: Weak Signal from Low-Abundance Targets

Symptoms:

- Faint or undetectable signal from specific targets despite proper labeling

- Poor signal-to-noise ratio for specific markers

- Inability to visualize targets of interest against background

Solutions:

- Enhance Detection Efficiency

- Employ Signal Amplification Strategies

- Use tyramide signal amplification (TSA) for enhanced detection

- Implement enzymatic amplification methods

- Consider multi-layer immunolabeling approaches

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Titrating Dye Concentrations for Balanced Emission

Purpose: To establish optimal dye concentrations that achieve balanced emission intensities across multiple channels, minimizing spectral bleed-through.

Materials:

- Target-specific antibodies or labeling reagents

- Fluorophore conjugates (e.g., Alexa Fluor series, FITC, PE) [32]

- Single-stained control samples

- Flow cytometer or confocal microscope [33]

Procedure:

- Prepare a series of dye concentrations for each fluorophore conjugate (e.g., 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 μg/mL)

- Label replicate samples with each concentration separately

- Acquire data using identical instrument settings for all samples

- Measure median fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each concentration [33]

- Plot MFI versus dye concentration for each fluorophore

- Identify concentrations that yield comparable MFI values across fluorophores

- Validate the selected concentrations in multicolor experiments using control samples

Expected Results: When properly balanced, no signal from single-stained controls should appear in channels reserved for other fluorophores.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Flow Cytometry for Target Abundance Measurement

Purpose: To quantify membrane target expression levels using flow cytometry with fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies [33].

Materials:

- Fluorophore-conjugated mAbs (e.g., PE-conjugated) [33]

- Cell lines expressing target of interest (e.g., HL-60, Daudi, Ramos) [33]

- Binding buffer (e.g., growth medium, BSA buffer, or PBS with human serum) [33]

- BD Quantibrite PE beads (for calibration) [33]

- Flow cytometer with appropriate lasers and detectors [33]

Procedure:

- Suspend cells in binding buffer at appropriate concentration (e.g., 2.5×10⁴ cells/sample) [33]

- Prepare serial dilutions of mAbs in the same binding buffer

- Combine cells and mAb solutions in 1:1 ratio

- Incubate for 45-120 minutes to achieve binding equilibrium (time depends on temperature) [33]

- Wash samples by adding excess buffer

- Acquire data using flow cytometer

- Generate calibration curve using Quantibrite PE beads [33]

- Determine median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in single-cell gates [33]

- Calculate Ab binding capacity (ABC) using calibration curve [33]

Data Analysis:

- Plot mAb concentrations vs. measured MFIs

- Fit data with non-linear regression: Y = Bmax*X / (Kd + X) [33]

- Extrapolate Bmax (maximum binding intensity) and apparent Kd [33]

- Calculate ABC using Bmax and calibration curve [33]

Data Presentation

Table 1: Fluorophore Properties and Optimal Filter Sets for Multicolor Imaging

| Fluorophore | Peak Excitation (nm) | Peak Emission (nm) | Recommended Filter Set | Relative Brightness | Compatible Laser Lines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPI | ~358 | ~461 | EX:375/30nm; DM:415nm; EM:460/50nm [32] | High | UV (355-375nm) |

| Alexa Fluor 488 | ~495 | ~519 | EX:475/30nm; DM:505nm; EM:530/40nm [32] | Very High | Argon (488nm) |

| FITC | ~495 | ~519 | EX:475/30nm; DM:505nm; EM:530/40nm [32] | High | Argon (488nm) |

| Alexa Fluor 546 | ~556 | ~573 | EX:540/25nm; DM:565nm; EM:605/55nm [32] | High | Green HeNe (543nm) |

| PE | ~496, ~546 | ~578 | EX:540/25nm; DM:565nm; EM:605/55nm [32] | Very High | Argon (488nm) |

| Alexa Fluor 647 | ~650 | ~665 | EX:635-650nm; DM:660nm; EM:665-700nm [34] | High | Red HeNe (633nm) |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Emission Intensity Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe bleed-through in one channel | Emission imbalance, spectral overlap | Use sequential scanning, adjust detection bandwidths, apply spectral unmixing [6] | Select fluorophores with minimal spectral overlap, prepare single-stained controls [6] |

| Weak signal from low-abundance targets | Insufficient dye concentration, poor target accessibility | Increase dye concentration, use signal amplification methods, optimize staining conditions | Titrate antibodies for optimal signal, use bright fluorophores for low-abundance targets [6] |

| High background across all channels | Non-specific binding, autofluorescence | Include blocking steps, use heparin blocking [31], optimize wash steps | Include appropriate controls, use clean reagents, optimize buffer composition |

| Inconsistent results between experiments | Variation in dye lots, instrument drift | Standardize protocols, use reference standards, calibrate instruments regularly | Use same reagent lots, implement routine instrument QC, maintain detailed records |

| Photobleaching during imaging | High laser power, insufficient mounting medium | Reduce illumination intensity, use antifade reagents, optimize acquisition speed | Titrate laser power, use photostable dyes, limit exposure time |

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: Spectral Bleed-Through Mechanism and Correction

Diagram 2: Emission Intensity Balancing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Emission Intensity Balancing Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Example Products | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Antibodies | Target-specific labeling | Alexa Fluor series, FITC, PE [32] | Brightness, photostability, conjugation ratio [33] |

| Reference Beads | Instrument calibration and quantification | BD Quantibrite PE Beads [33] | Match fluorophore type, establish standard curve |

| Blocking Reagents | Reduce non-specific binding | Heparin, BSA, serum proteins [31] | Target tissue-specific (e.g., heparin for charge-based blocking) [31] |

| Mounting Media | Preserve samples and reduce photobleaching | Antifade reagents, ProLong Diamond | Compatibility with fluorophores, hardening properties |

| Control Samples | Assay validation and optimization | Single-stained cells, negative controls [6] | Essential for assessing bleed-through and setting gates |

| Spectral Unmixing Software | Post-acquisition signal separation | Linear unmixing algorithms, cluster analysis tools [6] | Requires reference spectra from control samples [6] |

| Flow Cytometry Calibration Kits | Absolute quantification | BD Quantibrite PE Beads [33] | Enables ABC (Antibody Binding Capacity) calculation [33] |

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is Spectral Bleed-Through? Spectral bleed-through (also termed crossover or crosstalk) is a phenomenon where the fluorescence emission from one fluorophore is detected in the photomultiplier channel or through the filter set reserved for a second fluorophore [1]. This artifact fundamentally arises from the very broad and asymmetrical spectral profiles exhibited by many common fluorophores, where their emission spectra can span a wavelength band of 50 to 150 nanometers or more [1] [8]. This poses a significant challenge for experiments involving multiple fluorescent labels, especially those requiring precise quantification, such as co-localization studies, Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), and photobleaching (FRAP) assays [1] [35].

The Underlying Spectral Principles The absorption and emission spectra of a fluorophore are not symmetrical. Absorption spectra are generally skewed towards shorter wavelengths (the blue end of the spectrum), while emission spectra are skewed towards longer wavelengths (the red end) [1]. Consequently, crossover can occur during both excitation and emission. A key practical implication is that emission from a green fluorophore can often be detected through red emission filters, but a red dye is seldom imaged through a green emission filter [1]. Understanding this asymmetry is critical for configuring your microscope correctly.

Instrument Configuration Guidelines

Fine-tuning your instrument involves a systematic approach to the excitation source, the detection pathway, and the choice of fluorophores. The following table summarizes the primary tools at your disposal.

Table 1: Instrument Components for Bleed-Through Control

| Component | Function | Adjustment Principle | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Power | Controls fluorophore excitation intensity. | Use minimal power necessary to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio [36]. | High power can cause saturation, non-linear signals, and exacerbate bleed-through by overwhelming dimmer channels [36]. |

| Detector Slits / Bandpass | Defines the range of emitted light collected by the detector. | Set slit widths or bandpass filters to encompass the primary emission peak of the target fluorophore while excluding the emission tails of others [1]. | Excessively narrow slits improve separation but reduce signal intensity. Widening slits to capture more signal often also captures bleed-through [1]. |

| Spectral Unmixing | A computational method to separate overlapping emission signals after acquisition. | Acquire a "lambda stack" (images across a spectrum) and use reference spectra from control samples to digitally unmix signals [37] [8]. | Requires reference spectra from singly-labeled specimens imaged under identical conditions. Success depends on high signal-to-noise and avoiding saturated pixels [37]. |

| Sequential Scanning | Scans the specimen with each laser line individually and detects emission sequentially. | Eliminates simultaneous excitation of multiple fluorophores, preventing excitation crosstalk [1]. | Slower than simultaneous scanning. Requires precise registration between channels to avoid image shift. |

A. Fine-Tuning Laser Power and Detector Settings

The goal is to balance sufficient signal for the target fluorophore without capturing excessive bleed-through from others.

- Laser Power: Begin with low laser power and gradually increase until you obtain a clear signal above background. A saturated signal is non-linear and cannot be used for reliable quantification. Furthermore, an overly bright signal in one channel can overwhelm and bleed into adjacent detector channels [1] [36].

- Detector Gain/PMT Voltage: Adjust the detector gain after setting laser power. Similar to laser power, use the minimum gain necessary. High gain can amplify noise along with the signal.

- Detector Slits and Bandpass Filters: This is a critical step for physical separation. Configure the emission detection window to be as narrow as possible while still capturing the core emission of your fluorophore. For example, if bleed-through from Alexa Fluor 488 is detected in the Cy3 channel, ensure the Cy3 detection slit is not so wide that it collects the long-wavelength tail of Alexa Fluor 488 emission [1]. Modern software often allows for precise digital control of these slit widths.

B. The Critical Role of Filter Sets

The selection of excitation and emission filters, along with the dichromatic mirror (beamsplitter), is fundamental [38]. A filter cube must be carefully chosen to match the spectral profiles of your specific fluorophores.

- Excitation Filter: Should allow transmission of light that efficiently excites the target fluorophore but minimizes excitation of other fluorophores in the specimen.

- Emission Filter (Barrier Filter): Should transmit the emission light of the target fluorophore while blocking the emission spectra of other fluorophores. Narrow bandpass filters (e.g., 20-30 nm) offer better separation than longpass filters [8] [36].

- Dichromatic Mirror: Reflects the excitation light to the specimen and transmits the emitted light to the detector. Its cut-on/cut-off wavelength must be precisely positioned between the excitation and emission peaks of the fluorophore.

Table 2: Example Filter Optimization for Common Fluorophore Pairs

| Fluorophore Pair | Excitation Lines | Recommended Emission Bandpass | Rationale and Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Cy3 | 488 nm, 543 nm | 500-530 nm (AF488); 555-625 nm (Cy3) | The Cy3 channel is wide to capture its emission, but this also collects AF488 tail emission, causing bleed-through. Substituting Cy3 with Alexa Fluor 594 significantly reduces overlap [1]. |

| ECFP & EYFP | 405 nm/458 nm, 514 nm | 460-500 nm (ECFP); 525-555 nm (EYFP) | These fluorescent proteins have highly overlapping spectra. Sequential scanning with narrow bandpass filters or spectral unmixing is essential to separate signals [8]. |

| Alexa Fluor 488 & Alexa Fluor 633 | 488 nm, 640 nm | 500-540 nm (AF488); 650-700 nm (AF633) | Excellent spectral separation with virtually no overlap. Bleed-through artifacts are absent even with high fluorophore concentrations [1]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: Despite using recommended filter sets, I still see significant bleed-through in my multi-color experiment. What are the most common causes? The most common cause is an imbalance in fluorophore signal intensities [1] [37]. If one fluorophore is extremely bright (e.g., from an abundant target or high expression) and another is dim, the bright signal can overwhelm the emission filters of the dimmer channel. Other causes include using fluorophores with excessively overlapping spectra (e.g., ECFP and EGFP) or suboptimal detector slit widths that are too wide [1] [8].

Q2: How can I proactively minimize bleed-through during experimental design? The most effective strategy is the judicious selection of fluorophores with well-separated emission spectra [1]. Reserve the brightest and most photostable fluorophores for the least abundant cellular targets [1]. Furthermore, during specimen preparation, carefully balance the concentrations or expression levels of your probes to achieve similar fluorescence intensities [1] [37]. Computational tools are also available to help design optimal multi-color panels based on your specific instrument configuration [39].

Q3: What is the difference between sequential and simultaneous scanning, and when should I use each? Simultaneous scanning uses all laser lines at once to image all channels concurrently. It is faster but can cause excitation crosstalk, where one laser excites multiple fluorophores. Sequential scanning illuminates the specimen with one laser line at a time and collects emission for only one channel per scan. This eliminates excitation crosstalk and is the preferred method for quantitative work, despite being slightly slower [1].

Q4: My microscope has a spectral detector. What are the critical steps for effective linear unmixing? Successful linear unmixing depends on high-quality reference spectra [37] [8].

- Acquire Reference Spectra: Image control specimens labeled with a single fluorophore under the exact same conditions (objective, laser power, gain, etc.) as your experimental sample.

- Avoid Saturation: Ensure no pixels in your reference or experimental images are saturated, as this distorts the spectral profile.

- Balance Signals: Strive for relatively balanced signal intensities across all fluorophores in your experimental sample. A very bright fluorophore can compromise the unmixing of weaker ones [37].

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Sequential Scanning to Minimize Bleed-Through

This protocol is designed for a laser scanning confocal microscope.

- Define Acquisition Settings: Open your microscope's acquisition software and set up the channels for each fluorophore, assigning the correct laser line and emission detection window (slit or bandpass) for each.

- Configure Sequential Mode: In the acquisition settings, select "Sequential scan" or "Frame switching" mode instead of "Simultaneous" mode.

- Set Laser and Detection Order: Program the sequence to image the fluorophore with the longest excitation wavelength first, using an excitation wavelength that is minimally absorbed by the other fluorophores. This leverages the spectral skewing of absorption profiles to reduce unintended excitation [1].

- Fine-Tune per Channel: For each channel in the sequence, independently adjust the laser power, detector gain, and offset to optimize the signal without saturation. The settings for one channel do not affect the others in sequential mode.

- Acquire Image: Run the acquisition. The microscope will scan the specimen multiple times, once for each laser/detector channel combination, and then merge the images.

Protocol: Acquiring Reference Spectra for Linear Unmixing

- Prepare Control Samples: Create specimens that are identical to your experimental sample in every way except that they are labeled with only one of the fluorophores you plan to use in the final experiment.

- Set Imaging Parameters: Define all imaging parameters (laser power, gain, objective, pinhole size, etc.) for your experimental lambda stack acquisition.

- Acquire Lambda Stacks: For each control specimen, acquire a spectral lambda stack (a series of images across the emission spectrum). It is critical that all parameters from Step 2 remain identical for every control and the final experimental sample [37].

- Build a Reference Library: In the unmixing software, use the lambda stacks from the control samples to create a library of reference emission spectra for each fluorophore.

- Unmix the Experimental Sample: Acquire a lambda stack of your multiply-labeled experimental specimen using the same settings. The software will then use the reference library to calculate the contribution of each fluorophore to every pixel in the experimental image.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bleed-Through Reduction

| Item | Function / Utility | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorophores with Well-Separated Spectra | Probes with minimal emission spectrum overlap significantly reduce the potential for bleed-through at the source. | Using Alexa Fluor 488 (green) with Alexa Fluor 633 (far-red) instead of Alexa Fluor 555 (red) for a two-color experiment [1]. |

| Single-Labeled Reference Specimens | Control samples containing only one fluorophore each are essential for generating accurate reference spectra for linear unmixing. | Culturing cells that express only one fluorescent protein (e.g., EYFP) for use as a reference standard [37]. |

| Mounting Media with Antifade Reagents | Reduces photobleaching during imaging, allowing for lower laser powers and longer acquisitions, which helps maintain signal balance. | Using ProLong Live Antifade Reagent for live-cell single-molecule tracking to preserve fluorescence [40]. |

| Computational Panel Design Tools | Algorithmic software that helps select an optimal set of fluorophores for a given instrument configuration to maximize signal and minimize bleed-through. | Using open-source tools like FPselection to design a 4-color panel for a flow cytometer or microscope [39]. |

The Critical Role of Single-Stained Controls for System Calibration and Unmixing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is spectral bleed-through and why is it a problem? Spectral bleed-through (also called crosstalk) occurs when the fluorescence emission from one fluorophore is detected in the channel reserved for another fluorophore [1]. This happens due to the broad and overlapping emission spectra of many fluorescent dyes [1] [6]. This artifact can lead to serious errors in data interpretation, such as false co-localization in multi-labeling experiments or compromised quantitative measurements in techniques like FRET or FRAP [1] [6].

2. Why are single-stained controls preferable to compensation beads? Single-stained cells treated identically to your full-panel sample account for cell-specific factors like autofluorescence and the unique staining pattern of your target antigen [11]. Compensation beads, while easy to use, do not accurately replicate the spectral signature of an antibody bound to a cellular target. Using beads, especially for multiple markers in a large panel, introduces inaccuracies in unmixing, whereas single-stained cells provide a true reference for the fluorophore's emission profile on your sample [11].

3. How can I create a good single-stained control for a dimly expressed marker? If your marker of interest is dimly expressed, you can use an antibody conjugated with the same fluorophore from the same manufacturer but targeting a bright, ubiquitously expressed antigen (like CD4 or CD8 on relevant cells) instead [11]. This provides a strong, clean signal for the fluorophore's spectral signature. The key is to keep all other staining conditions (buffer, volume, time) identical to your full-panel protocol [11].

4. My single-stained control is contaminated with autofluorescence. What should I do? Tighten your scatter gate to focus on the population of interest and exclude highly autofluorescent cells (e.g., macrophages) [11]. For complex samples, you can extract the autofluorescence profile as a separate channel during unmixing. Alternatively, use a different antibody with the same fluorophore that stains a non-autofluorescent cell type, or in worst-case scenarios, use compensation beads, acknowledging the potential for introduced error [11].

5. Can I use a library of pre-recorded control spectra? Yes, many modern spectral cytometers allow you to store control data in a reference library [11]. However, the accuracy of these stored references may degrade over time as instrument performance drifts. While using a few library controls is acceptable, relying on them for a large panel or using very old controls will reduce unmixing accuracy. Fresh controls are always best [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Unmixing Problems

Poor unmixing can create spillover errors that lead to incorrect biological conclusions. Here are key indicators that your unmixing may be flawed [11]:

- Incorrect Single-Stain Signals: In your single-color control, the positively stained population does not appear neutral (neither above nor below the negative population) in other channels.

- Asymmetrical "Hypernegative" Events: The appearance of distinctly negative populations that are not symmetrical with positive spreading errors.

- Unexpected Positive Correlations: Observing strong linear correlations between markers that are not biologically related (e.g., TCR and CD3 are an exception, not the rule).

- Biologically Impossible Populations: Identifying cell populations that cannot exist biologically, such as seeing four distinct, well-separated populations in a CD4 vs. CD8 plot from a mixed bone marrow chimera.

- Data Curving: The data in a bivariate plot curves up or down as the expression level of a marker increases.

- Massive Spreading: An inability to distinguish where the positive population begins due to extreme spreading of the negative population.

Experimental Protocol: Preparing Optimal Single-Stained Controls

For reliable spectral unmixing, the single-stained control must be an exact replica of the staining conditions in the full panel.

| Protocol Step | Critical Parameters & Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Cell Source | Use the same cell type or tissue as your experiment. For rare markers, prepare and freeze aliquots of positive control cells for future use [11]. |

| 2. Staining Identity | Use the same antibody clone, fluorophore conjugate, and dilution factor as in the full panel [11]. |