Advanced Strategies for Handling Light Scattering in Biological Tissues: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of light scattering in biological tissues, a major obstacle in biomedical optics.

Advanced Strategies for Handling Light Scattering in Biological Tissues: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of light scattering in biological tissues, a major obstacle in biomedical optics. It explores foundational principles of light-tissue interactions, surveys established and emerging methodological approaches like synthetic wavelength imaging and dynamic light scattering, and provides practical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing signal penetration and resolution. The article also examines validation frameworks and comparative performance of various technologies, highlighting their translational potential in clinical diagnostics, drug development, and therapeutic monitoring. Designed for researchers, scientists, and pharmaceutical professionals, this resource synthesizes recent advancements to empower more effective implementation of optical technologies in complex biological systems.

Understanding Light-Tissue Interactions: The Fundamental Physics of Scattering in Biological Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental optical properties of tissue that cause light scattering?

Tissue scattering is primarily governed by its scattering coefficient (µs) and the scattering anisotropy factor (g). These properties arise from spatial variations in the refractive index (n) within the tissue. The reduced scattering coefficient (µ's) combines these two factors and, across a wide spectral range, is well-described by a combination of Rayleigh and Mie scattering regimes [1]:

µ's(λ) = a' × ( f_Ray × (λ/500 nm)^-4 + (1 - f_Ray) × (λ/500 nm)^-b_Mie )

where a' is the reduced scattering coefficient at 500 nm, f_Ray is the Rayleigh scattering fraction, and b_Mie is the Mie scattering exponent related to the average scatterer size [1].

FAQ 2: Why is the refractive index so important in light scattering measurements? The refractive index is a critical parameter because it determines the phase velocity of light within the sample. In techniques like Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS), the refractive index is essential for converting the measured BLS frequency shift (νB) into the hypersonic acoustic speed (V) of phonons propagating through the material, which is then related to the sample's viscoelastic modulus [2]. An accurate value is necessary for quantitative mechanical property mapping.

FAQ 3: My Brillouin light scattering data is inconsistent between different instruments. What crucial parameters should I report? To ensure comparability between BLS studies, a recent consensus statement recommends always reporting the following parameters [2]:

- Spectrometer Details: Type of spectrometer, its Free Spectral Range (FSR), and sampling step size.

- Spectral Resolution: The smallest detectable frequency change, often determined by measuring the width of a spectrally narrow laser line.

- Key Measured Parameters: The Brillouin frequency shift (νB) and the Brillouin linewidth (ΓB).

- Spatial Resolution: This should be determined experimentally using mock-up systems with sharp interfaces between different materials, as the effective resolution can be larger than that of incoherent probes due to the coherent nature of the photon-phonon interactions [2].

FAQ 4: How does tissue heterogeneity specifically affect light scattering signals? Heterogeneity introduces complexity at multiple levels. Variations in the size, density, and composition of cellular organelles (e.g., nuclei, mitochondria) and extracellular matrix components create a complex refractive index landscape. This leads to multiple scattering events, which can corrupt signals in techniques like fluorescence microscopy, turning sharp images into noisy speckle patterns [3]. In scattering-based imaging, this heterogeneity can also reduce the coherence of acoustic phonons, which in turn affects the spatial resolution of techniques like BLS [2].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low signal-to-noise in DLS measurements. | Sample is too polydisperse or at a high concentration, leading to multiple scattering. | Use Multi-Angle Dynamic Light Scattering (MADLS) to remove angular bias and improve size distribution accuracy. Dilute the sample to avoid multiple scattering effects [4]. |

| Poor spatial resolution in scattering images. | High heterogeneity causing elongated phonon coherence or scattering-induced blurring. | Determine the true spatial resolution experimentally using a mock sample with a sharp interface. For deep tissue fluorescence, use a computational framework like RNP that uses sparse representation to extract object features from speckle patterns [2] [3]. |

| Inaccurate extraction of mechanical properties from BLS. | Incorrect values for refractive index or mass density used in calculations. | Perform angle-resolved BLS measurements or use several scattering geometries to determine the refractive index more accurately, assuming a homogeneous sample [2]. |

| Low contrast in label-free imaging of cells. | Sample is too translucent; incident light is not sufficiently scattered. | Employ a technique like bidirectional quantitative scattering microscopy (BiQSM), which unifies detection of forward and backward scatter to resolve both micro- and nanoscale features [5]. |

| Inability to differentiate healthy and pathological tissues based on optical properties. | Standard optical properties provide insufficient contrast. | Apply an optical clearing method using immersion agents to reduce scattering dynamically, enhancing the contrast between healthy and pathological tissue regions [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Optical Properties and Their Relationship to Tissue Heterogeneity

| Optical Property | Symbol & Formula | Relation to Tissue Heterogeneity | Typical Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient | µ's(λ) [See FAQ1] |

Indicates the overall strength of scattering. A higher µ's suggests a greater density and/or size of scattering organelles [1]. |

Inverse adding-doubling, spatial frequency domain imaging [1]. |

| Scattering Anisotropy | g(λ) = 1 - µ's(λ)/µs(λ) [1] |

Describes the directionality of scattering. g ≈ 1 implies forward scattering (large structures), g ≈ 0 implies isotropic scattering (small structures) [1]. |

Derived from measured µ's and µs. |

| Brillouin Frequency Shift | νB [2] |

Probes the hypersonic speed, related to the longitudinal modulus M'. Heterogeneity can broaden the Brillouin linewidth ΓB [2]. |

Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS) Microscopy [2]. |

| Refractive Index | n_tissue(λ) (e.g., Cauchy: A + B/λ² + C/λ⁴) [1] |

Determined by the molecular composition and packing density of tissue components. Spatial variations in n are the direct cause of light scattering [1]. |

Total internal reflection, multi-wavelength refractometry [1]. |

| Landau-Placzek Ratio | rLP = I_Rayleigh / I_Brillouin [2] |

In homogeneous materials, relates to specific heat ratio. In complex tissues, it is affected by other elastic scattering processes and is often avoided [2]. | Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS) Spectroscopy [2]. |

Protocol: Measuring Broadband Optical Properties of Ex Vivo Tissue

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a uniform slab of tissue of known thickness (d).

- Spectral Measurement: Measure the total transmittance (Tt(λ)), total reflectance (Rt(λ)), and collimated transmittance (Tc(λ)) spectra of the sample.

- Calculate Absorption Coefficient: Use the diffusion approximation to calculate the absorption coefficient spectrum [1]:

μa(λ) = [1 - Tt(λ) + Rt(λ)] / d - Calculate Scattering Coefficient: Use the Bouguer-Beer-Lambert relation to find the scattering coefficient spectrum [1]:

μs(λ) = -ln[Tc(λ)] / d - μa(λ) - Estimate Reduced Scattering Coefficient: Perform inverse simulations to estimate µ's at discrete wavelengths, then fit the data to the power-law equation provided in FAQ1 to obtain the broadband µ's(λ) spectrum [1].

- Determine Refractive Index: Measure the refractive index at discrete wavelengths using a method like total internal reflection. Fit the discrete values with a dispersion curve (e.g., Cauchy's equation) to estimate the broadband tissue dispersion [1].

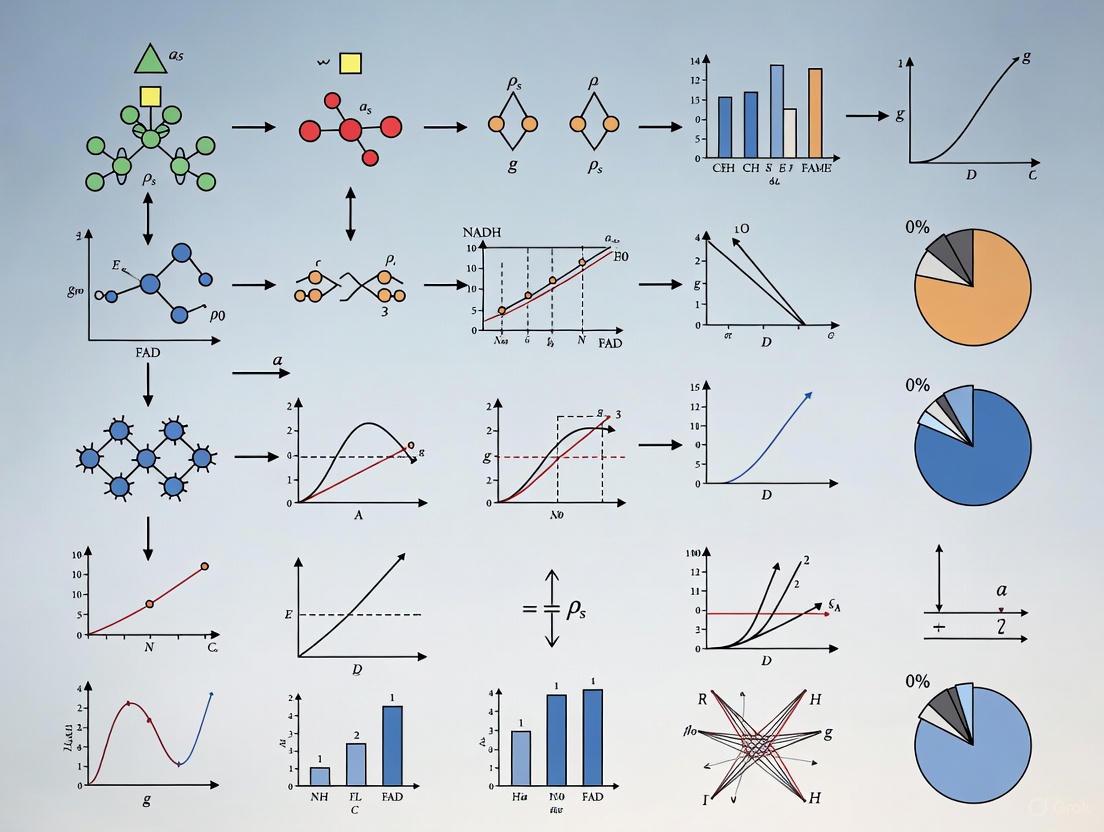

Experimental Workflow and Scattering Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Light Scattering Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Optical Clearing Agents (OCAs) | Chemicals (e.g., glycerol, iohexol) that reduce light scattering by matching the refractive index of the tissue extracellular medium to that of cellular components, thereby improving imaging depth and contrast [1]. |

| Index-Matching Fluids | Liquids with known refractive indices, used in setups like total internal reflection microscopes to accurately determine the critical angle and calculate the sample's refractive index [1]. |

| Standard Reference Samples (e.g., Cyclohexane) | Used for calibration and benchmarking of instruments like Brillouin spectrometers. Their well-defined BLS frequency shift and linewidth help validate experimental setups [2]. |

| Monodisperse Polystyrene Beads | Particles with a uniform, known size. They serve as calibration standards for dynamic light scattering (DLS) and laser diffraction instruments, and as scattering targets in imaging system resolution tests [3]. |

| Stable Colloidal Suspensions | Used for system performance verification in DLS and laser diffraction. A stable suspension ensures that measured fluctuations are due to Brownian motion and not aggregation or sedimentation [4]. |

| Microfluidic Phantoms | Devices containing channels of precise dimensions, used to simulate blood flow or particle movement for validating techniques like Multi-Exposure Speckle Imaging (MESI) [3]. |

Core Theoretical Frameworks: FAQ

FAQ 1: What is Mie Theory and when should it be used in tissue research? Mie Theory is an exact solution to Maxwell's equations for the scattering of an electromagnetic plane wave by a homogeneous sphere [6]. It is a critical foundational model in biophotonics.

You should consider using Mie Theory under the following conditions:

- Particle Size: The size of the scattering particles (e.g., organelles, microspheres) is comparable to the wavelength of the incident light (typically in the range of 0.4 to 2.0 μm) [7].

- Particle Geometry: The scatterers can be reasonably approximated as spheres or spheroids. While it is a spherical model, Mie theory has been successfully used to discern the geometry of spheroidal scatterers, such as cell nuclei [8].

- Contrast Mechanism: You are measuring elastic (wavelength-conserving) light scattering signals to infer structural properties.

It is less suitable for highly irregular or interconnected structures, where modeling tissue as a continuous random medium may be more appropriate [9].

FAQ 2: What is an Inverse Scattering Problem in this context? An inverse scattering problem refers to the process of deducing the physical properties of a scatterer (e.g., its size, shape, and refractive index) from measurements of its scattered light field [8] [10]. This is a cornerstone of many optical diagnostic techniques.

The process is considered "ill-posed," meaning that different combinations of object properties can produce similar scattered fields, making the solution sensitive to measurement noise and requiring robust computational methods to find the most probable solution [10] [11]. For example, Inverse Light Scattering Analysis (ILSA) compares measured angular scattering distributions to a database of theoretical models (like Mie theory) to identify the most probable scattering geometry [8].

FAQ 3: Why is my Mie-based size estimation inaccurate for biological cells? Inaccuracies often arise from a model-to-reality mismatch. The primary sources of error include:

- Non-Spherical Geometry: Cell nuclei and other organelles are often spheroidal or have more complex shapes. Using a spherical model (Mie) for a non-spherical object can introduce errors, though it can still provide a good estimate of one major axis of a spheroid [8].

- Orientation: The orientation of a non-spherical scatterer (e.g., with its symmetry axis parallel or transverse to the light propagation direction) significantly affects the scattering signature and can change which dimension (polar or equatorial) is accurately retrieved by a spherical model [8].

- Internal Complexity: Cells are a collection of many different scatterers (mitochondria, nuclei, cytoskeleton) with a distribution of sizes. A single-size Mie model may not capture this complexity, leading to a measurement that represents an "effective" size [7].

- Polarization: The polarization state of the incident light can interact differently with various scatterer orientations, affecting the measurement outcome [8].

FAQ 4: How can I isolate singly-scattered light from deeply scattered light in tissue? A common method is Polarization Gating. This technique exploits the fact that light scattered multiple times in a turbid medium tends to lose its original polarization state, while singly-scattered light largely retains it [10].

Experimental Protocol: Polarization-Gated Light Scattering Spectroscopy (LSS)

- Illuminate the tissue with linearly polarized light from a broadband source.

- Collect the backscattered light and pass it through a polarization analyzer.

- Take two sequential measurements: one with the analyzer parallel ((I{\parallel})) and one perpendicular ((I{\perp})) to the illumination polarization axis.

- Subtract the two measurements: ( \Delta I = I{\perp} - I{\parallel} ). The result ((\Delta I)) is a signal enriched for photons that were scattered only a small number of times (primarily singly-scattered) from the superficial epithelial layer [10].

- Analyze the spectrum of (\Delta I) using an inverse model (e.g., based on Mie theory) to determine the size distribution of scatterers like cell nuclei.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Handling Non-Spherical Scatterers (e.g., Spheroidal Nuclei)

- Problem: Mie theory (spherical model) is being used to analyze scattering from spheroidal particles, leading to biased size estimates.

- Solution: Implement a more advanced inverse model that uses a non-spherical theory, such as the T-Matrix method, for generating the reference database [8]. If you must use Mie theory, understand its limitations: it can provide a good estimate of either the equatorial or polar diameter of a spheroid, depending on the particle's orientation and the incident light polarization [8].

- Methodology:

- Forward Modeling: Use T-Matrix theory to simulate scattering distributions from spheroidal particles with a range of sizes, aspect ratios, and orientations [8].

- Data Collection: Acquire an angular scattering distribution from your sample using a technique like a/LCI (angle-resolved Low-Coherence Interferometry) [8].

- Inverse Analysis: Compare your measured distribution to the T-Matrix database using a χ² minimization procedure to find the most probable spheroidal geometry [8].

Challenge 2: Accounting for Tissue as a Continuous Scattering Medium

- Problem: Tissue is a complex, interconnected medium, not a collection of discrete particles, making discrete models like Mie theory less physically representative.

- Solution: Model the tissue as a continuous random medium characterized by a refractive index correlation function, such as the Whittle-Matérn model [9].

- Methodology (Inverse Spectroscopic OCT):

- Model: The Whittle-Matérn correlation function describes the statistical fluctuations in refractive index, from which all scattering properties (e.g., scattering coefficient, anisotropy) can be derived [9].

- Data Acquisition: Use Spectroscopic Optical Coherence Tomography (SOCT) to obtain depth-resolved scattering information across multiple wavelengths [10] [12].

- Inverse Calculation: Fit the wavelength-dependent scattering data to the Whittle-Matérn model to inversely deduce physical parameters like the correlation length and the Hurst exponent, which quantify the characteristic length scale and "roughness" of the tissue ultrastructure [12] [9].

Challenge 3: Solving Ill-Posed Inverse Problems with Noisy Data

- Problem: The inverse problem is unstable, and small errors in measured scattering data can lead to large errors in the reconstructed object properties.

- Solution: Utilize regularization techniques and modern data-driven approaches.

- Methodology:

- Classical Regularization: Incorporate constraints (e.g., smoothness) into the inverse problem to penalize unrealistic solutions and ensure stability [10].

- Bayesian Framework: Treat the inverse problem statistically, using prior knowledge about the system to compute a distribution of probable solutions rather than a single answer [13].

- Deep Learning: Train a deep neural network on a large dataset of paired scattering measurements and ground-truth object properties. The network learns a mapping that can directly reconstruct properties from noisy data, often showing improved robustness to noise [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Light Scattering Experiments.

| Item | Function in Experiment | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Microspheres | Used as calibration phantoms to validate instrument performance and inverse algorithms. Known size and refractive index. | Refractive index ~1.59 at 589 nm [8]. |

| Cell Culture Monolayers | In vitro model for investigating light scattering from cellular and subcellular structures. | Enables controlled studies of nuclear morphology [8]. |

| T-Matrix Code | Computational tool for calculating scattering from non-spherical particles (e.g., spheroids). | Used to generate test data for evaluating Mie-based inverse algorithms [8]. |

| Monte Carlo Simulator (e.g., ValoMC) | Models light propagation in complex, multi-layered tissues with user-defined geometry. | Essential for designing experiments and interpreting signals in diffuse scattering regimes [13]. |

| Whittle-Matérn Scattering Model | A flexible model for light scattering from continuous random media, suitable for tissue. | Overcomes limitations of discrete particle models; can be applied to OCT data [9]. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for solving an inverse scattering problem in a biological context, from data acquisition to structural interpretation.

Inverse Scattering Problem Workflow

The logical relationship between a chosen scattering model and the type of structural information it can reveal is outlined below.

Model-Information Relationship

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental optical properties that describe light propagation in biological tissues? Biological tissues are characterized by three key intrinsic optical properties that govern how light propagates through them [14] [15]:

- Absorption coefficient (μa): Quantifies how likely a photon is to be absorbed per unit path length, providing information about molecular concentrations like hemoglobin, water, and melanin.

- Scattering coefficient (μs): Describes the probability of photon scattering per unit path length, related to tissue microarchitecture and ultrastructures.

- Anisotropy factor (g): Represents the average cosine of the scattering angle, indicating whether scattering is primarily forward-directed (g close to 1) or more isotropic (g close to 0).

Q2: Which experimental techniques are most reliable for measuring absorption and scattering coefficients in ex vivo tissue samples? For ex vivo tissue characterization, integrating sphere systems combined with analytical models provide reliable measurements [16] [15]:

- Double integrating sphere setups simultaneously measure total reflectance and transmittance.

- The Kubelka-Munk model offers a straightforward analytical solution for calculating μa and μs from reflectance/transmittance data.

- Inverse adding-doubling methods provide higher accuracy, especially for strongly absorbing samples, through iterative computational approaches. These methods typically employ laser wavelengths in the red to near-infrared spectrum (600-900 nm) where tissue penetration is optimal.

Q3: How does tissue preparation affect optical property measurements, and how can researchers control for these variables? Tissue condition significantly impacts optical measurements [16]:

- Hydration state: Hydrated skin shows markedly different fluorescence emission and scattering profiles compared to dry skin.

- Thermal effects: Boiling adipose tissue alters its absorption and scattering characteristics.

- Sample thickness: Must be optimized for transmission measurements (typically 2-3 mm for accurate KM model application). Standardize preparation protocols, document conditions thoroughly, and use control samples from the same source to minimize variability.

Q4: What advanced imaging techniques can overcome scattering limitations for deep tissue imaging? Several next-generation technologies address scattering challenges [17] [18]:

- Synthetic Wavelength Imaging (SWI): Uses multiple illumination wavelengths to create virtual, longer wavelengths that scatter less while preserving contrast.

- Robust Non-negative Principal matrix factorization (RNP): Computational approach that extracts structural information from speckle patterns in scattering environments.

- Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS): Measures viscoelastic properties through hypersonic acoustic phonon detection, requiring careful interpretation in complex tissues [2]. These methods enable deeper penetration while maintaining resolution, though each has specific instrumentation requirements.

Q5: How can researchers validate the accuracy of their optical property measurements? Validation strategies include [16] [2]:

- Statistical analysis: Partial least squares regression with R-squared values >0.85 indicates good measurement accuracy.

- Phantom studies: Use tissue-simulating phantoms with known optical properties.

- Cross-validation: Compare results from multiple techniques (e.g., KM model vs. inverse adding-doubling).

- Consensus parameters: Follow established reporting guidelines for techniques like Brillouin light scattering [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Optical Property Measurements Across Samples

Problem: High variability in measured absorption and scattering coefficients between tissue samples that should be similar.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Uncontrolled tissue hydration | Implement standardized hydration control protocols; measure and report tissue hydration state [16]. |

| Variable sample thickness | Use precision micrometers (e.g., digital Mitutoyo micrometer) to ensure uniform thickness (2±0.5 mm for skin, 3±0.4 mm for adipose) [16]. |

| Inadequate calibration | Regularly calibrate with reference standards (barium sulfate/Spectralon coatings) using single or double integrating sphere setups [15]. |

| Thermal history variations | Document and control for thermal effects; avoid sample heating during preparation [16]. |

Validation Protocol:

- Prepare tissue phantoms with known optical properties

- Measure using your established system

- Compare results with theoretical values

- Calculate coefficient of variation between repeated measurements

- Accept if <5% variation, otherwise recalibrate instrumentation

Issue: Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Deep Tissue Imaging

Problem: Low contrast and resolution when imaging through thick, scattering tissues.

Advanced Solutions:

| Technique | Application | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| RNP Algorithm | Fluorescence imaging through scattering media | Integrate robust feature extraction with non-negativity constraints on standard epi-fluorescence platforms [18]. |

| Synthetic Wavelength Imaging | Deep tissue imaging with preserved contrast | Use two separate illumination wavelengths to computationally generate synthetic wavelengths [17]. |

| Multi-angle Dynamic Light Scattering | Polydisperse nanoparticle systems | Employ multiple detection angles (MADLS) to remove angular bias and improve size distribution accuracy [4]. |

Workflow Optimization:

Deep Tissue Imaging Troubleshooting Workflow

Issue: Artifacts in Mechanical Property Measurements Using Brillouin Spectroscopy

Problem: Inconsistent or unreliable Brillouin frequency shifts (νB) and linewidth (ΓB) measurements in biological tissues.

Troubleshooting Steps:

Spectrometer Validation [2]:

- Measure reference samples (e.g., distilled water, cyclohexane)

- Verify νB = 6.35 GHz and ΓB = 5.17 GHz for water at 20°C

- Confirm spectral resolution using narrow laser line

Sample Preparation Considerations:

- Control temperature fluctuations (affects phonon frequency)

- Minimize external vibrations

- Ensure proper refractive index matching

Reporting Standards Compliance [2]:

- Document spectrometer type and free spectral range (FSR)

- Report spectral resolution and sampling parameters

- Specify scattering geometry and data fitting methods

Critical Parameters Table for BLS:

| Parameter | Typical Range | Reporting Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Resolution | 10 MHz - 1 GHz | Must report method of determination |

| Free Spectral Range | Instrument-dependent | Essential for interpretation |

| Acquisition Time | Seconds to hours | Must report for reproducibility |

| Spatial Resolution | ~200 nm - microns | Determine experimentally with mock systems |

| Temperature Control | ±0.1°C | Critical for soft matter |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Optical Properties Using Integrating Spheres and KM Theory

Objective: Quantify absorption (μa) and scattering (μs) coefficients of ex vivo tissue samples.

Materials and Equipment:

| Item | Function | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Double Integrating Sphere | Simultaneous reflectance/transmittance | Barium sulfate/Spectralon coating |

| Spectrometer | Detect diffuse light | USB2000 FLG or equivalent [16] |

| Laser Source | Multiple wavelengths | 808, 830, 980 nm for NIR window [16] |

| Digital Micrometer | Sample thickness | Mitutoyo Digimatic or equivalent [16] |

| Tissue Samples | Fresh or prepared | 2-3 mm thickness, uniform preparation |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Obtain fresh tissue samples (bovine adipose, chicken skin)

- Clean with running water, pat dry with paper towels

- Measure thickness at multiple points using digital micrometer

- For comparative studies: create dry (24h air drying) and boiled (1min in distilled water) samples [16]

System Calibration:

- Use white reflectance standards for baseline correction

- Measure background without sample

- Verify sphere integrity and coating reflectivity

Measurement:

- Place sample between two integrating spheres

- Illuminate with selected laser wavelengths (808, 830, 980 nm)

- Record diffuse reflectance (Rd) and transmittance (Td)

- Repeat for multiple sample locations

Calculation:

- Apply Kubelka-Munk equations:

- S = (1/d) × [ln((1 - R × (a - b)) / T)] / b

- K = S × (a - 1)

- Where a = (1 + R² - T²) / (2R) and b = √(a² - 1)

- Convert to absorption and scattering coefficients: μa ≈ K and μs ≈ S [16]

- Apply Kubelka-Munk equations:

Validation:

- Perform partial least squares regression (target R-squared >0.85)

- Compare with inverse adding-doubling method

- Test with tissue phantoms of known properties

Protocol 2: Fluorescence Imaging Through Scattering Media Using RNP

Objective: Achieve high-quality fluorescence imaging through turbid biological tissues.

Materials:

| Item | Function | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Epi-fluorescence Microscope | Core imaging platform | Standard wide-field configuration [18] |

| Motorized Rotating Diffuser | Generate speckle illumination | Programmable speed control |

| sCMOS Camera | Image capture | High sensitivity, low noise |

| Scattering Media | Experimental challenge | Tissue sections, hydrogel films (800μm thickness) [18] |

| Fluorescent Samples | Validation | Microspheres (4μm, 16μm), labeled cells |

Procedure:

- System Setup [18]:

- Configure upright wide-field fluorescence microscope

- Incorporate motorized rotating diffuser in illumination path

- Position sCMOS camera for detection

- No complex alignment required

Image Acquisition:

- Collect raw speckle images through multiple illumination cycles

- Capture background references

- Maintain consistent exposure across samples

RNP Processing:

- Stage 1: Fourier domain filtering for contrast enhancement and noise removal

- Stage 2: Robust decomposition into sparse features (Sk) and low-rank background (Lk)

- Stage 3: Non-negative matrix factorization for dimensionality reduction

- Stage 4: Image reconstruction from emitter positions

Validation:

- Compare with ground truth (non-scattered images)

- Measure signal-to-noise ratio improvement

- Quantify resolution using microsphere separations

RNP Algorithm Processing Steps

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Optical Tissue Characterization:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spectralon/Barium Sulfate | Integrating sphere coating | High reflectivity (>99%) across visible-NIR spectrum [15] |

| Tissue-simulating Phantoms | System validation | Lipids/intralipid for scattering, ink/dyes for absorption [16] |

| Fluorescent Microspheres | Resolution validation | 4μm and 16μm diameters for system calibration [18] |

| Scattering Hydrogel Films | Controlled scattering media | ∼2.5 mean free paths at 800μm thickness [18] |

| Reference Standards | Calibration | White reflectance standards, known refractive index materials [16] |

| Optical Clearing Agents | Reduced scattering | Glycerol, focused ultrasound for improved penetration [17] |

Typical Optical Property Ranges in Biological Tissues [14] [15]:

| Tissue Type | Absorption Coefficient (μa) cm⁻¹ | Reduced Scattering Coefficient (μs') cm⁻¹ | Anisotropy Factor (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | 0.1 - 5.0 | 10 - 50 | 0.85 - 0.95 |

| Adipose | 0.2 - 3.0 | 5 - 30 | 0.80 - 0.90 |

| Brain | 0.2 - 4.0 | 10 - 40 | 0.85 - 0.95 |

| Liver | 0.3 - 6.0 | 15 - 45 | 0.90 - 0.97 |

Note: Values depend strongly on wavelength and tissue condition. Reduced scattering coefficient μs' = μs(1-g).

Comparison of Measurement Techniques [16] [15]:

| Method | Accuracy | Complexity | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrating Sphere + KM | Moderate | Low | Homogeneous samples, initial screening | Less accurate for low-scattering media |

| Inverse Adding-Doubling | High | Medium | Strongly absorbing samples | Computational complexity |

| Time-Resolved Spectroscopy | High | High | Separating absorption/scattering | Expensive equipment, complex analysis |

| Spatially Resolved Reflectance | Medium | Medium | Non-invasive in vivo measurements | Limited to superficial layers |

Technical FAQs: Resolving Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why do my measured tissue scattering values differ from published literature?

Differences between your data and published values often stem from the measurement context—in-vivo versus ex-vivo conditions. In-vivo measurements account for active blood flow and hydration, while ex-vivo samples undergo chemical and physical changes that alter their optical properties [19]. Furthermore, the specific spectrophotometer model and its configuration can cause variations of up to 40% in optical density readings for the same sample, primarily due to differences in how instruments collect scattered light [20]. To ensure consistency, always calibrate your equipment with standard phantoms, report the exact measurement geometry, and note whether data was acquired in-vivo or ex-vivo.

FAQ 2: How does incident laser power affect tissue scattering measurements?

Contrary to intuition, tissue scattering is not purely wavelength-dependent; it is also influenced by incident laser power. Experimental data shows that the scattering coefficient (μₛ′) of rat skull and skin decreases as incident laser power increases from 150 mW to 350 mW at a constant 808 nm wavelength [21]. This reduction is attributed to laser-induced thermal effects, such as minor coagulation or changes in tissue anisotropy, which alter scattering structures. For reproducible results, maintain a consistent, documented laser power and a short exposure duration to minimize thermal effects during measurements.

FAQ 3: My light scattering detector shows a persistently high and noisy baseline. What is the cause?

A high, noisy baseline in light scattering detectors is frequently caused by contamination from the system itself, particularly from new chromatography columns. These columns can shed nanoscale particles or fragments that are detected as high-molar-mass contaminants [22]. This problem is pronounced in aqueous systems and at low detection angles. To resolve this, flush new columns extensively according to the manufacturer's instructions before connecting them to the detector. Installing a filter between the column and detector can also help, but ensure its pore size is small enough to capture the contaminants without increasing backpressure or absorbing your sample.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Abnormal Scattering Coefficients

| Observed Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Scattering coefficient is too high | • Excessive sample concentration/optical density [20]• Significant contribution from absorption (e.g., high pigmentation) [20]• Incorrect model assumption (e.g., using diffusion theory for low-scattering tissue) | • Dilute sample and re-measure.• Measure at a "robust" wavelength less affected by absorption [20].• Verify that the chosen theoretical model matches the measurement geometry. |

| Scattering coefficient is too low | • High incident laser power altering tissue properties [21]• Detector saturation or signal loss• Contamination or air bubbles in optical path | • Reduce laser power and ensure short exposure times.• Check detector linearity and signal-to-noise ratio.• Inspect and clean sample chamber and cuvette. |

| Inconsistent measurements between replicates | • Inhomogeneous sample (e.g., tissue structure variation) [21]• False positives from sampling large, sparse agglomerates in DLS [23]• Temperature fluctuations | • Ensure representative sampling; homogenize if possible.• Perform at least 3 replicate aliquots as per ASTM standards [23].• Use a temperature-controlled stage. |

Guide 2: Addressing FTIR/ATR Spectral Quality Issues in Tissue

| Problem | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Strong, Broad Water Bands | Incomplete drying of biological sample dominates spectrum [24]. | Air-dry or use a nitrogen gas flow to desiccate the sample. Monitor the spectrum in real-time during drying until water bands (e.g., ~1650 cm⁻¹, 3000-3700 cm⁻¹) are minimized [24]. |

| Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio | • Sample too thin for ATR contact [25]• Insufficient scans averaged | • Ensure good, uniform contact between tissue and ATR crystal. Apply consistent pressure.• Increase the number of scans; 64 or 128 is common for biological samples. |

| Spectral Artifacts & Baseline Shift | • Scattering from rough tissue surface [24]• Mie scattering from large cellular structures [24] | Apply standard pre-processing steps: vector normalization, baseline correction, and smoothing [24]. For ATR spectra, apply the correction algorithm supplied by the instrument software [25]. |

Quantitative Data Reference

Table 1: In-Vivo Tissue Scattering Coefficients (μs') by Wavelength and Site

Data adapted from time-resolved spectroscopy measurements on human subjects [26].

| Tissue Site | μs' at 760 nm (mm⁻¹) | μs' at 800 nm (mm⁻¹) | μs' at 900 nm (mm⁻¹) | Wavelength Dependence (mm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forearm | ~0.73 | ~0.69 | ~0.64 | μs'(λ) ≈ 1.1 - (5.1×10⁻⁴ λ) |

| Calf | ~0.92 | ~0.89 | ~0.80 | μs'(λ) ≈ 1.6 - (8.9×10⁻⁴ λ) |

| Head | ~0.95 | ~0.93 | ~0.86 | μs'(λ) ≈ 1.45 - (6.5×10⁻⁴ λ) |

Table 2: Effect of Incident Laser Power on Tissue Scattering (808 nm)

Data shows the inverse relationship between laser power and scattering coefficient in rat tissues [21].

| Incident Laser Power (mW) | Scattering Coefficient (μs') - Skull | Scattering Coefficient (μs') - Skin |

|---|---|---|

| 150 | Highest | Highest |

| 200 | ↓ Decreasing | ↓ Decreasing |

| 250 | ↓ Decreasing | ↓ Decreasing |

| 300 | ↓ Decreasing | ↓ Decreasing |

| 350 | Lowest | Lowest |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Optical Properties Using an Integrating Sphere and Kubelka-Munk Model

This method is used to calculate the absorption (μₐ) and reduced scattering (μₛ′) coefficients of excised tissue samples [21].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Excise and clean tissue samples (e.g., rat skull or skin). Cut them to fit the integrating sphere's sample holder. Precisely measure the sample thickness using a micrometer [21].

- System Calibration: Perform baseline measurements with an empty integrating sphere to record the inherent reflectance (R) and transmittance (T) of the system itself [21].

- Reflectance Measurement (R_d): Place the sample at the upper port of the integrating sphere. Direct the input laser onto the sample and use the detector to capture the diffusely reflected light [21].

- Transmittance Measurement (T_d): Place the sample inside the sphere. Direct the laser to probe the sample, and record the total transmitted light detected [21].

- Data Processing with Kubelka-Munk Model:

- Use the measured Rd and Td to calculate the Kubelka-Munk absorption (AKM) and scattering (SKM) coefficients using the formulas:

S_KM = (1/(Y*D)) * ln( [1 - R_d*(X - Y)] / T_d )andA_KM = (X - 1) * S_KM[21]. - Where X and Y are derived from Rd and Td.

- Use the measured Rd and Td to calculate the Kubelka-Munk absorption (AKM) and scattering (SKM) coefficients using the formulas:

- Convert to Standard Coefficients: Finally, convert the Kubelka-Munk coefficients to the familiar absorption and reduced scattering coefficients:

μₐ = A_KM / 2andμₛ' = (4/3) * S_KM + (1/3) * μₐ[21].

Protocol 2: In-Vivo Skin Optical Properties Measurement with a Multi-Distance Diffusing Probe

This non-invasive protocol uses a multi-distance probe to separate absorption from scattering in living skin [19].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Instrument Setup: Employ a diffusing probe with a Spectralon layer and multiple source-detector separations (e.g., 1.44, 1.92, 2.4, and 2.88 mm) connected to a broadband light source and spectrometer [19].

- Data Acquisition: Place the probe in gentle contact with the skin site. Sequentially acquire the reflectance spectrum at each of the four source-detector separations [19].

- Signal Normalization: Normalize the reflectance from the three longer-distance pairs (1.92, 2.4, 2.88 mm) to the reflectance from the shortest pair (1.44 mm). This creates a normalized reflectance curve versus source-detector separation and helps self-calibrate for instrument response [19].

- Inverse Problem Solution: Fit the normalized reflectance curve to a modified two-layer diffusion model using a least-squares minimization algorithm. This fit directly returns the absorption (μₐ) and reduced scattering (μₛ′) spectra of the skin [19].

- Two-Region Spectral Analysis: For more accurate results, fit the recovered absorption spectrum to known chromophore spectra (e.g., oxy-hemoglobin, deoxy-hemoglobin, melanin) in two separate wavelength regions: 500-600 nm and 600-1000 nm. This accounts for the different sampling depths and optical properties in the visible and near-infrared ranges [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Scattering Experiments in Tissues

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Integrating Sphere | Measures total diffuse reflectance and transmittance from tissue samples for Kubelka-Munk analysis [21]. | Choose sphere diameter and port size based on sample dimensions and expected signal strength. |

| Spectralon Diffusing Layer | Integrated into probes for in-vivo measurements; creates a uniform light source, enabling the use of diffusion theory at short source-detector separations [19]. | Ensure it is firmly attached and flush with the optical fibers in the probe. |

| ATR-FTIR Crystal (Diamond/Ge) | Enables FTIR spectroscopy of tissues with minimal sample preparation via Attenuated Total Reflection [24] [25]. | Select crystal material based on required IR range and hardness (e.g., Diamond for durability, Ge for high refractive index). |

| Kubelka-Munk Model | A mathematical model used to calculate absorption and scattering coefficients from experimentally measured reflectance and transmittance data [21]. | Best applied when the radiance is predominantly diffuse. Requires accurate measurement of sample thickness. |

| Multi-Distance Diffusing Probe | Allows separation of μₐ and μₛ′ in superficial tissues in-vivo by measuring reflectance at multiple source-detector distances [19]. | The shortest source-detector separation should be >1 mm to comply with diffusion model assumptions [19]. |

Evanescent Waves and Near-Field Effects at Tissue Interfaces

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My evanescent wave measurements in biological tissues show inconsistent results. What could be causing this? Inconsistencies often arise from poor control of the interface conditions and sample preparation. Biological tissues are inherently heterogeneous, and variations in surface contact with the prism or waveguide can drastically alter the evanescent field penetration. Ensure your tissue samples have consistent thickness and hydration levels. The presence of a thin fluid layer between the tissue and the generating interface can invalidate the total internal reflection condition. Furthermore, the birefringent nature of many biological tissues (like muscle or derma) can alter the polarization of the evanescent wave, affecting the resulting optical forces and measurements [27].

Q2: How can I distinguish between propagating waves and evanescent waves in bounded biological media like the cornea or skin? In bounded media like the cornea, traditional Rayleigh-Lamb modes are highly dispersive, making quantification difficult. Supershear Evanescent Waves (SEWs) offer a solution. SEWs propagate along the surface faster than the bulk shear wave speed (approximately 1.95 times the shear wave speed, cs). They arrive before other modes and their amplitude decays rapidly with propagation distance due to leakage into the bulk. Tracking the local maximum of the wavefront can provide a direct, non-dispersive measure for quantifying elasticity [28].

Q3: Can I use evanescent waves to manipulate nanoparticles for drug delivery or cellular interaction studies? Yes. Evanescent waves can generate transverse optical forces capable of manipulating nano-objects. For instance, a linearly polarized wave (with a polarization azimuth of 45°) creating an evanescent field at a prism-biological medium interface can exert forces perpendicular to the wave's direction of propagation. This has been demonstrated for moving gold nanoparticles and red blood cells in a biological medium. The transverse spin component of the evanescent wave is key to this manipulation, enabling controlled motion parallel to the interface [27].

Q4: What are the common pitfalls when using Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS) to measure viscoelastic properties with near-field effects? A recent consensus statement highlights critical pitfalls in BLS microscopy [2]:

- Spectral Resolution and Fitting: Improper fitting of the Brillouin peaks (Stokes and anti-Stokes) leads to inaccurate frequency shift (νB) and linewidth (ΓB) values, which are essential for calculating viscoelastic moduli.

- Spatial Resolution Misinterpretation: The spatial resolution is not solely defined by the microscope's point spread function. It is also affected by the phonon coherence length in the sample, which depends on the phonon wavelength and its lifetime.

- Reporting: Failing to report key spectrometer parameters like the Free Spectral Range (FSR), sampling step size, and spectral resolution makes it impossible to compare or reproduce results.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Contrast in Label-Free Evanescent Wave Imaging

Issue: When using total internal reflection (TIR) for label-free imaging of biological samples (e.g., cells, tissues), the resulting image contrast is poor, making it difficult to distinguish structural details.

Solution: A proposed solution is a TIR-based near-field illumination technique that uses the auto-fluorescence of a coverglass to create a high-contrast, dark-field-like image [3].

- Procedure:

- Couple 488nm light into a coverglass so it guides light via TIR.

- The guided light generates auto-fluorescence in the glass, which in turn provides near-field illumination to the sample placed on the coverglass.

- Capture the light scattered by the sample. The background remains dark, yielding high-contrast images of structures like bull sperm cells without labels.

- Verification: First, test the system on standardized samples like polystyrene spheres (~5.2 μm) and compare the results and size measurement accuracy with Bright Field (BF) microscopy to validate performance [3].

Problem: Extracting Fluorescence Signals Through Scattering Tissue

Issue: When trying to image fluorescently labeled structures obscured by a layer of scattering biological tissue, the signal is degraded into a random speckle pattern, making reconstruction impossible.

Solution: Use the Robust Non-negative Principal matrix factorization (RNP) framework, which is designed to extract meaningful features from speckle patterns generated under random illumination [3] [18].

- Procedure:

- Setup: Use a standard epi-fluorescence microscope equipped with a motorized rotating diffuser to generate random speckle illumination on the sample.

- Algorithm Workflow:

- Capture multiple speckle images (

I_k). - Pre-process images with Fourier domain filtering to enhance contrast.

- Decompose each image into a sparse feature component (

S_k) and a low-rank redundant background component (L_k). This step crucially enhances the speckle contrast. - Apply non-negative matrix factorization to the decomposed features to assign speckle patterns to their corresponding emitters and reconstruct the final image.

- Capture multiple speckle images (

- Verification: The method has been validated by imaging 4-μm fluorescent microspheres through various scattering media, including an 800-μm-thick scattering hydrogel film (~2.5 mean free paths). It reliably recovered the signal-to-noise ratio and resolved adjacent microspheres [18].

Problem: Quantifying Elasticity in Thin, Bounded Tissues

Issue: Conventional surface wave analysis fails to give a simple, quantitative elasticity value in thin, bounded tissues like the cornea or skin because the waves become complex, dispersive Rayleigh-Lamb modes.

Solution: Employ Supershear Evanescent Waves (SEWs) probed by a high-speed Optical Coherence Elastography (OCE) system [28].

- Procedure:

- Excitation: Use a non-contact acoustic micro-tapping (AμT) method to launch a broadband mechanical pulse at the air-tissue interface. The AμT push should have a lateral width of about 0.5 mm and a duration of 100-200 μs.

- Detection: Track the wave propagation in real-time with a high-speed phase-sensitive OCT (PhS-OCT) system.

- Analysis: Identify the SEW in the wavefield. It will separate from other modes a few millimeters from the excitation point. Measure the propagation speed of the SEW's local maximum. The shear wave speed cs is then calculated as SEW speed / 1.955. The Young's modulus can be derived from cs.

- Verification: This method has been tested in tissue-mimicking phantoms, ex vivo human cornea, and in vivo human skin. In a 0.5 mm thick phantom, the SEW was clearly distinguishable from dispersive Rayleigh-Lamb modes 5-6 mm from the source [28].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Manipulating Nanoparticles with Transverse Spin

This protocol details the use of the transverse spin of an evanescent wave to exert force on nanoparticles in a biological medium [27].

Key Reagents and Materials:

| Item | Function/Specification |

|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | Biologically inert, can penetrate cell membranes for diagnostic/therapeutic applications. |

| Prism | To create the interface for Total Internal Reflection (TIR). |

| Linearly Polarized Laser Source | Wavelength in the "transparency window" of biological tissue (e.g., 800-1500 nm). |

| Biological Tissue Sample | e.g., a section of derma (50-100 μm thick). |

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the experimental setup and the mechanism of transverse force generation.

Key Steps:

- Direct a linearly polarized laser beam with a polarization azimuth of 45° onto a prism to establish TIR at the prism-biological medium interface.

- This creates an elliptically polarized evanescent wave at the interface. The 45° azimuth is critical for maximizing the wave's ellipticity and its transverse spin component.

- Introduce the nanoparticles (e.g., gold) into the biological medium near the interface.

- The transverse spin momentum density of the evanescent wave generates an optical force (

F_y) perpendicular to the wave vector. This force can push particles along the interface, enabling controlled manipulation.

Protocol 2: Elasticity Mapping via Supershear Evanescent Waves (SEWs)

This protocol describes using SEWs measured by OCE to quantify tissue elasticity [28].

Key Reagents and Materials:

| Item | Function/Specification |

|---|---|

| Tissue-Mimicking Phantoms | e.g., Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) cryogels of varying concentrations (4, 8, 12 wt.%) for validation. |

| Air-Coupled Ultrasound Transducer | 1 MHz, cylindrically focused, for non-contact mechanical excitation (AμT). |

| High-Speed PhS-OCT System | For real-time, 3D tracking of mechanical wave propagation. |

Quantitative Data from Phantom Studies: The following table summarizes key relationships established in phantom and theoretical studies.

| Parameter | Relationship/Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

SEW Speed (c_SEW) |

≈ 1.955 · cs | Theoretical maximum for an impulsive line source on an elastic half-space [28]. |

| SEW Speed in Bounded Media | (1.95 - 1.98) · cs | Finite element simulations in phantoms with thickness (0.5 - 1.0 mm) > push width [28]. |

| Linear Regression (R²) | 0.888 - 0.912 | Microfluidic flow measurements using a lensless MESI system with an optical fiber bundle [3]. |

Workflow: The diagram below outlines the key steps for data acquisition and processing in SEW-based OCE.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Cryogels | Tissue-mimicking phantoms with tunable mechanical and optical properties [28]. | Validating OCE and SEW measurements; system calibration. |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Biocompatible probes for optical manipulation and diagnostic applications [27]. | Studying targeted drug delivery and cellular interactions using evanescent wave-based manipulation. |

| Interdigital Transducers (IDTs) | Piezoelectric devices for excitation and registration of acoustic waves, including evanescent ones [29]. | Studying evanescent acoustic waves in piezoelectric plates for sensor development. |

| Optical Fiber Bundle | Flexible light guide for lensless speckle imaging in confined spaces [3]. | Enabling perfusion measurements (MESI) in endoscopic, handheld, or bandage-integrated systems. |

| Rotating Diffuser | Optical component to generate random speckle illumination [18]. | Creating the varying patterns required for computational imaging through scattering media (e.g., RNP framework). |

| Y-X Cut LiNbO3 (Lithium Niobate) Plate | Piezoelectric substrate for guiding high-frequency acoustic waves [29]. | Experimental platform for studying the properties of evanescent acoustic waves and their sensitivity to surface conditions. |

Advanced Imaging and Sensing Technologies: Methodological Approaches for Real-World Applications

Synthetic Wavelength Imaging (SWI) represents a significant computational imaging breakthrough designed to overcome the fundamental limitations of conventional optical techniques in biomedical applications. Funded by a $2.7 million NIH grant, researchers at the University of Arizona are pioneering SWI to provide deeper, clearer views inside the body without invasive procedures [30] [31]. This technology is particularly targeted at improving the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of nonmelanoma skin cancers, such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma [30] [31].

The core challenge in biomedical optics is the resolution-depth-contrast tradeoff. Current methods like confocal microscopy or optical coherence tomography use short-wavelength light in the visible to near-infrared spectrum, offering superior contrast and resolution at shallow tissue depths but becoming susceptible to light scattering deeper inside biological tissue [31]. SWI addresses this by using two separate illumination wavelengths to computationally generate a third, virtual "synthetic" wavelength [31]. This longer synthetic wavelength is more resistant to light scattering, enabling deeper penetration while preserving the high-contrast information from the original shorter wavelengths [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary clinical target for SWI development? The current research specifically focuses on nonmelanoma skin cancers. These cancers present a unique imaging challenge as they display significantly different imaging contrast properties than melanoma and often present with lesions that vary widely in size, depth, and pattern of invasion [30] [31].

How does SWI fundamentally differ from existing optical coherence tomography? While both are optical techniques, SWI advances beyond traditional OCT by synthesizing the complex optical fields of two closely-spaced wavelengths into a third field at a much longer "beat" wavelength. This synthesized wavelength is more resistant to light scattering inside tissue, overcoming the traditional depth-resolution compromise [30].

What are the potential long-term applications beyond skin cancer? Researchers anticipate that the wide tunability of the synthetic wavelength opens up additional avenues in biomedical imaging through strongly scattering tissue. Potential future applications include novel detection methods for breast cancer or imaging deep inside the human brain [31].

Is SWI intended to replace biopsies? The goal is to develop a non-invasive platform for skin cancer diagnosis that could allow earlier detection of invasive lesions and monitoring of therapies in real time. This could potentially reduce the need for some biopsies and allow interventions to be tailored individually to each patient [30] [31].

Troubleshooting Guide for SWI Experiments

Problem 1: Inadequate Tissue Penetration Depth

- Symptoms: Signal loss or excessive noise when imaging beyond superficial tissue layers.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Suboptimal wavelength pairing for the specific tissue type.

- Cause: High scattering in the sample overwhelming the signal.

- Solution: Implement advanced computational evaluation algorithms designed to extract meaningful data from the scattered light signals [30].

Problem 2: Poor Image Contrast/Resolution

- Symptoms: Images appear blurry or lack definition to distinguish key tissue structures.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Loss of high-frequency information from the original optical wavelengths.

- Solution: Recalibrate the computational synthesis process to better leverage the high-contrast information provided by the original, shorter illumination wavelengths. The strength of SWI lies in combining the deep penetration of a long synthetic wavelength with the high contrast of short optical wavelengths [31] [32].

- Cause: Inadequate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

- Solution: Optimize detector sensitivity and integration time for the synthetic wavelength signal.

- Cause: Loss of high-frequency information from the original optical wavelengths.

Problem 3: System Calibration Drift

- Symptoms: Gradual degradation of image quality over time without changes to the sample.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Misalignment of the two independent light paths for

λ1andλ2.- Solution: Establish a routine calibration protocol using standardized phantoms with known scattering properties to ensure the coherence and precise overlap of the two wavefronts [31].

- Cause: Misalignment of the two independent light paths for

Experimental Protocols for Key SWI Applications

Protocol 1: Imaging Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Margins

Objective: To accurately assess the lateral and deep margins of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas.

Workflow:

- Patient Positioning: Secure the area of interest, typically a suspected lesion on the skin.

- Wavelength Selection: Select and calibrate the two primary illumination wavelengths (

λ1,λ2) based on the expected depth and optical properties of the lesion. - Data Acquisition: Scan the lesion and surrounding tissue, capturing the complex optical fields for both wavelengths.

- Computational Synthesis: Process the acquired data to generate the synthetic wavelength (

Λ) dataset. - Image Reconstruction & Analysis: Use advanced algorithms to reconstruct a high-contrast, deep-tissue image. Analyze the image to delineate tumor boundaries and depth of invasion [31].

Protocol 2: Monitoring Treatment Response

Objective: To non-invasively monitor changes in tumor volume and morphology during non-invasive therapies.

Workflow:

- Baseline Imaging: Perform a comprehensive SWI scan of the lesion prior to treatment initiation.

- Follow-up Imaging: At predetermined intervals (e.g., weekly), repeat the SWI scan under identical system parameters.

- Longitudinal Data Registration: Use computational methods to co-register the baseline and follow-up images.

- Quantitative Comparison: Analyze the registered images for changes in lesion size, depth, and internal structure to assess treatment efficacy in real time [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Key components for a Synthetic Wavelength Imaging system and their functions in biomedical research.

| Component/Reagent | Function in SWI Experiment |

|---|---|

| Tunable Dual-Wavelength Laser Source | Provides the two coherent light sources (λ1, λ2) required to generate the synthetic wavelength. Tunability allows optimization for different tissues [31] [32]. |

| High-Sensitivity Photodetector Array | Captures the reflected or back-scattered complex optical fields from the biological tissue with high fidelity [31]. |

| Computational Synthesis Algorithm | The core software that mathematically combines the data from λ1 and λ2 to generate the synthetic wavelength dataset, enabling deep-tissue penetration with high contrast [30] [31]. |

| Tissue-Simulating Phantoms | Standardized samples with known optical scattering and absorption properties. Used for system calibration, validation, and troubleshooting [31]. |

| Advanced Image Processing Software | Reconstructs the final high-contrast image from the synthetic wavelength data, often incorporating models of light-tissue interaction to improve accuracy [30] [31]. |

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 2: Comparative analysis of SWI against established optical imaging techniques for tissue imaging.

| Imaging Modality | Typical Imaging Depth | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confocal Microscopy | Superficial layers (up to ~500 μm) | High resolution at cellular level | Very limited depth penetration; strong scattering in deeper tissue [31]. |

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Shallow to moderate (1-2 mm) | Superior contrast and resolution at shallow depths | Short imaging wavelengths make it susceptible to scattering deep inside tissue [31]. |

| Ultrasound | Deep (cm range) | Good penetration depth | Often lacks resolution or sufficient optical contrast for certain cancer types [31]. |

| Synthetic Wavelength Imaging (SWI) | Deeper than conventional optical methods | Breaks resolution-depth-contrast tradeoff; resilient to scattering while preserving high contrast [30] [31]. | Technology is still in development; requires sophisticated computational processing and calibration. |

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Diffuse Correlation Spectroscopy (DCS) for Microvascular Flow

Troubleshooting Guides

Common DCS Instrumentation and Signal Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Issue & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Quality | Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), erratic Blood Flow Index (BFI) [33] | • Insufficient photon count rate [33]• Source-detector separation too large [33]• Low laser power or poor probe contact | • Verify photon count rate; aim for a stable, high rate (e.g., ~11 kcps at 25 mm separation) [33]• Reduce source-detector separation if possible, balancing with depth sensitivity needs [33]• Check laser output and ensure proper optical probe contact with tissue |

| Signal contamination from superficial tissue layers [33] | • High sensitivity of DCS to scalp/skull blood flow compared to cerebral blood flow [33] | • Use longer source-detector separations (>25 mm) to improve depth sensitivity [33]• Employ advanced techniques like time-gated DCS to select for longer (deeper) photon paths [34] | |

| Motion Artifacts | BFI signal spikes or steps during measurement [35] | • Subject movement causing probe-tissue interface disruption• Intense muscle contraction during physiological protocols [36] | • Secure optical probe firmly with elastic bandages or a customized holder• For muscle studies, acquire data during brief periods of muscle relaxation between contractions [36] |

| Data Interpretation | BFI underestimates true blood flow changes, especially in muscle [36] | • Changes in blood vessel diameter (vasodilation/constriction) are not accounted for in the standard BFI model [36] | • Apply a correction factor using concomitant NIRS-derived total hemoglobin (HbTot) to estimate changes in microvascular flow area [36] |

Common DLS Sample Preparation and Measurement Errors

| Problem Category | Specific Issue & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Large, erratic particles or "dust" appear in size distribution [37] [38] | • Contaminated cuvettes or sample buffers• Inadequate filtration of samples or buffers | • Meticulously clean cuvettes with filtered solvents and use powder-free gloves [38]• Filter all buffers and samples using a syringe filter with a pore size 3x larger than the expected particle size (e.g., 5 μm for nanoparticles) [37] |

| Sample Concentration | Measured size is inaccurate; intensity changes non-linearly with dilution [37] [39] | • Multiple scattering effects at high concentrations• Insufficient scattering signal at low concentrations [39] | • Perform a dilution series; the measured size should remain constant upon dilution [37]• Ensure the sample is "water clear to very slightly hazy;" opaque or milky samples require further dilution [37] |

| System Performance | Size results for a known standard are inconsistent or inaccurate [40] | • Improper instrument verification or alignment• Temperature fluctuations during measurement [39] | • Regularly verify instrument performance using certified size standards (e.g., 60-100 nm polystyrene latex) per ISO 22412 guidelines [40]• Allow the instrument and sample to equilibrate fully at the set temperature before measurement |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between DLS and DCS? While both are based on dynamic light scattering, they are applied in different contexts. DLS is typically used in vitro to determine the hydrodynamic size of nanoparticles or proteins in a cuvette by analyzing light scattering fluctuations from Brownian motion [41] [39]. DCS is an in vivo technique that uses near-infrared light to measure deep tissue blood flow by analyzing speckle fluctuations caused primarily by moving red blood cells in tissue microvessels [33] [35].

Q2: Why does my DCS blood flow index (BFI) seem to underestimate the large increase in muscle blood flow during exercise? This is a known challenge in skeletal muscle studies. The standard DCS BFI is predominantly sensitive to red blood cell (RBC) velocity. However, during exercise, increased blood flow is achieved through both increased RBC velocity and vasodilation (an increase in vessel cross-sectional area). The BFI does not fully account for the area component, leading to an underestimation. Recent research suggests adjusting the BFI with a co-acquired NIRS measurement of total hemoglobin content (HbTot), which serves as a proxy for changes in microvascular blood volume and area [36].

Q3: For cerebral monitoring with DCS, what is the optimal source-detector separation and why is it a compromise? A separation of 2.5 to 3.0 cm is commonly used. This is a trade-off between depth penetration and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Shorter separations (<1.5 cm) have excellent SNR but are primarily sensitive to superficial layers (scalp and skull). Longer separations (>3.0 cm) provide greater sensitivity to the brain but suffer from very low light levels, resulting in poor SNR and requiring longer measurement times [33].

Q4: My DLS sample is too concentrated. How do I know, and what should I do? Two simple checks can indicate an overly high concentration:

- Count Rate Check: If the photon count rate on your instrument is near or above 500-600 kcps, the concentration is likely too high and requires dilution [37].

- Dilution Test: Dilute your sample by 50%. If the measured size changes significantly or the scattering intensity does not drop by roughly half, your original sample was too concentrated. The sample should be diluted until the measured size remains constant upon further dilution [37].

Q5: What are the latest technological advancements in DCS to overcome its limitations? Active technical development is focused on:

- Improving SNR and Depth Sensitivity: Using multi-speckle detectors (e.g., SPAD cameras), heterodyne (interferometric) detection, and multi-source probes [33].

- Time-Domain DCS (TD-DCS): This advanced method uses pulsed lasers to measure the photon time-of-flight. It allows for "time-gating," which selectively analyzes photons that have traveled to deeper tissues, significantly improving sensitivity to cerebral blood flow and reducing superficial contamination [34].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: DCS Measurement of Muscle Blood Flow During Exercise

This protocol outlines the procedure for non-invasively monitoring changes in muscle blood flow using DCS during a handgrip exercise regimen, including the correction for vasodilation [36].

1. Equipment and Reagent Setup

- Primary Instrument: A combined DCS and Frequency-Domain NIRS (FDNIRS) system.

- DCS: Laser source (~850 nm), single-mode detection fibers, single-photon counting avalanche photodiodes (APDs), and a correlator board [33] [35].

- FDNIRS: System capable of measuring absorption (μa) and reduced scattering (μs') coefficients at multiple wavelengths to resolve oxy- (HbO2) and deoxy-hemoglobin (HHb) [36].

- Optical Probe: A custom probe housing one DCS source-detector pair (separation ~2.4 cm) and multiple FDNIRS source-detector pairs (e.g., 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.7 cm) [36].

- Exercise Equipment: Handgrip dynamometer.

- Other: Computer for data acquisition and analysis, probe fixation materials (e.g., elastic bandage, medical tape).

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Subject Preparation: Position the subject comfortably with the forearm supported. Clean the skin area over the flexor digitorum profundus muscle.

- Probe Placement: Secure the optical probe firmly over the muscle belly to prevent motion artifacts. Ensure good optical contact without impeding blood flow.

- Baseline Recording: Acquire at least 2 minutes of resting DCS and FDNIRS data [36].

- Exercise Protocol: Instruct the subject to perform handgrip exercise at a set intensity (e.g., 30% of maximum voluntary contraction). To minimize motion artifacts in the optical signals, program brief (e.g., 3-5 second) relaxation pauses at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) where data is acquired while the muscle is static [36].

- Post-Exercise Recovery: Record at least 5 minutes of data during passive recovery following the cessation of exercise [36].

- Data Processing:

- Fit the DCS intensity autocorrelation functions to the correlation diffusion equation to compute the blood flow index (BFi), incorporating a rolling average of the optical properties (μa, μs') derived from FDNIRS [36].

- Calculate total hemoglobin (HbTot = HbO2 + HHb) from the FDNIRS data.

- Determine the Hb-Nadir, defined as the difference between the peak HHb during a separate baseline arterial occlusion and the minimum HHb during subsequent reperfusion [36].

- BFi Adjustment for Vasodilation:

Protocol: Basic Particle Size Analysis using DLS

This protocol describes the standard procedure for determining the hydrodynamic size of nanoparticles in suspension using DLS.

1. Equipment and Reagent Setup

- Instrument: DLS instrument (e.g., Zetasizer Advance).

- Cuvettes: Disposable plastic microcuvettes for aqueous solutions or quartz cuvettes for organic solvents [40] [38]. Ensure cuvettes are designed for light scattering with multiple polished windows.

- Consumables: High-purity water (HPLC grade or better), salt (e.g., KNO3 or NaCl for buffer), syringes, 0.1 μm or 0.2 μm syringe filters (non-sterile, rinsed before use) [37]. Powder-free gloves [38].

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Diluent/Buffer Preparation: Prepare a clean aqueous diluent, such as 10 mM KNO3. Filter the diluent through a rinsed 0.1 or 0.2 μm filter to remove dust [37].

- Sample Preparation:

- For a dry powder, disperse it in the filtered diluent. Use gentle agitation (vortexing) or sonication as needed, avoiding aggressive methods for fragile samples like proteins [37].

- For a concentrated liquid sample, dilute a small aliquot into the filtered diluent. A 1:100 or 1:1000 dilution is a typical starting point [37].

- The ideal concentration results in a clear to slightly hazy solution.

- Cuvette Preparation:

- Wear powder-free gloves. Rinse the clean cuvette with filtered diluent at least three times [38].

- Dry the cuvette using compressed air from a can [38].

- Using a pipette with a plastic tip, transfer the prepared sample into the cuvette, avoiding the introduction of air bubbles [38].

- Wipe the external windows of the cuvette with a lens tissue designed for optics.

- Instrument Measurement:

- Verify the instrument using a certified latex size standard (e.g., 100 nm) according to manufacturer and ISO guidelines [40].

- Place the cuvette in the instrument and allow the sample to temperature equilibrate for 5-10 minutes [38].

- Set the measurement parameters (temperature, number of runs, angle). Use automatic attenuation for most use cases [40].

- Run the measurement. Perform at least 3-12 replicates to assess repeatability.

- Data Analysis:

- Report the Z-average diameter (the intensity-weighted mean hydrodynamic diameter) and the Polydispersity Index (PDI) as key parameters [40].

- Check the reproducibility of the Z-average and PDI across repeats. Consistent size distributions indicate a reliable measurement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Coherence Laser | DCS light source that creates a stable speckle pattern after light propagates through tissue. | Wavelengths in the NIR "biological window" (e.g., 785, 850 nm) are preferred for deep penetration [33] [35]. |

| Single-Photon Avalanche Diodes (SPADs) | DCS detectors that count individual photons and are sensitive enough to detect the weak light emerging from tissue. | Red-enhanced SPADs offer higher detection efficiency at NIR wavelengths. Arrays of SPADs can sample multiple speckles in parallel to improve SNR [33] [34]. |

| Multi-Tau Correlator | A digital board that computes the intensity autocorrelation function in real-time from the stream of photon arrival pulses. | Essential for processing the rapid fluctuations (>>100 Hz) that contain the blood flow information [33] [35]. |

| Optical Fibers & Probe | Deliver light to the tissue and collect scattered light. The probe defines the source-detector separation geometry. | Single-mode or few-mode fibers are used for detection to preserve speckle contrast [35]. The probe must be designed for stable skin attachment. |

| Certified Size Standards | For DLS instrument verification and performance qualification. | Typically polystyrene latex beads of a known size (e.g., 60 nm, 100 nm). Must be prepared in a specified buffer (e.g., 10 mM NaCl) [40]. |

| DLS Cuvettes | Hold the liquid sample for DLS measurement. | Must have multiple polished optical windows. Disposable plastic is suitable for aqueous samples; quartz is needed for organic solvents [40] [38]. |

| Syringe Filters | Remove dust and large aggregates from DLS samples and buffers to prevent measurement artifacts. | A pore size of 0.1 μm or 0.2 μm is standard. The pore size should be at least 3x larger than the largest particle to be measured to avoid filtration bias [37]. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

DCS Experimental Workflow

Time-Domain DCS (TD-DCS) Concept

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Localized SPR Biosensors for Biomarker Detection

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) are label-free, real-time optical sensing techniques that have become indispensable tools for studying biomolecular interactions, particularly in the context of biomarker detection. SPR technology is based on a quantum-electromagnetic phenomenon where photon energy excites collective oscillations of free electrons (surface plasmons) at a metal-dielectric interface. This resonance is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index within the evanescent field, typically within 100-300 nanometers of the sensor surface [42]. When biomolecules such as proteins, antibodies, or DNA bind to the functionalized sensor surface, the local refractive index changes, causing a measurable shift in the resonance angle or wavelength [43] [44].

LSPR operates on a similar principle but utilizes metal nanoparticles rather than continuous metal films. The confinement of surface plasmons to nanoscale structures results in enhanced electromagnetic fields at particle surfaces, producing wavelength-selective absorption and scattering with extremely high extinction coefficients [45]. The LSPR frequency is sensitive to changes in the local environment, including adsorbate binding events, nanoparticle size, shape, composition, and inter-particle spacing [45]. For researchers investigating light scattering in biological tissues, LSPR offers particular advantages due to its capacity for single nanoparticle spectroscopy and enhanced scattering signatures that can be distinguished from tissue autofluorescence.

The adaptation of SPR and LSPR for clinical biomarker detection represents a significant advancement over traditional methods. These technologies enable researchers to monitor binding events in real-time without fluorescent or radioactive labels, preserving native molecular activity while providing rich kinetic data including association rates (kon), dissociation rates (koff), and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) [43]. This technical profile explores the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions essential for implementing these powerful biosensing platforms in biomarker research and development.