Beyond Jellyfish: The Evolutionary Diversity and Biomedical Applications of GFP Analogs

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) family, tracing its phylogenetic journey from its discovery in Aequorea victoria to the vast diversity of analogs found...

Beyond Jellyfish: The Evolutionary Diversity and Biomedical Applications of GFP Analogs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) family, tracing its phylogenetic journey from its discovery in Aequorea victoria to the vast diversity of analogs found in coral reef Anthozoa. It details the structural and spectral evolution of these proteins, which has enabled a rainbow of fluorescent tools for biomedical research. For scientists and drug development professionals, the article critically examines the practical applications of these tools in receptor research, drug screening, and cellular tracking, while also addressing significant experimental challenges such as cytotoxicity, immunogenicity, and proper maturation kinetics. A comparative analysis of available analogs provides a framework for selecting optimal proteins for specific research goals, from high-throughput screening to advanced imaging in complex physiological models.

From Aequorea to Anthozoa: Unraveling the Evolutionary Tree of Fluorescent Proteins

The discovery of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) in the jellyfish Aequorea victoria and its intricate relationship with the photoprotein aequorin represents a cornerstone in the field of bioluminescence and a pivotal event for modern biological research. This system not only provides a classic example of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) in nature but also serves as a critical reference point in the phylogenetic distribution of GFP analogs across the tree of life. The initial identification was almost incidental; GFP was discovered fortuitously in 1962 by Osamu Shimomura and colleagues during their efforts to purify the bioluminescent protein aequorin from A. victoria [1] [2]. The subsequent realization that the green light emission was the result of non-radiative energy transfer from the blue-light-emitting aequorin to GFP provided a fundamental understanding of the jellyfish's bioluminescent system [1]. This natural FRET pair has since become a paradigmatic model for understanding molecular interactions and energy transfer, its principles now applied in countless laboratory-designed biosensors. For researchers investigating the evolutionary history of fluorescent proteins, the A. victoria GFP-aequorin system provides an essential anatomical and functional benchmark against which other discovered and resurrected fluorescent proteins can be compared [3].

Historical Context and Key Discoveries

The elucidation of the A. victoria light system was a feat of persistent biochemical effort. The following table summarizes the key milestones and the scientists involved.

Table 1: Historical Milestones in the Discovery of the Aequorea victoria GFP-Aequorin System

| Year | Key Discovery/Event | Principal Scientist(s) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Initial purification of aequorin and incidental discovery of a "green protein" | Osamu Shimomura et al. | First identification of GFP as a footnote; established the calcium-dependent bioluminescence of aequorin [1] [2]. |

| 1960s-1970s | Method development for large-scale protein collection from jellyfish | Shimomura, Frank Johnson | Enabled biochemical characterization by processing ~850,000 jellyfish to obtain sufficient protein for study [2]. |

| 1974 | Reconstitution of energy transfer from aequorin to GFP in vitro | Morise et al. | Provided direct experimental insight into the FRET mechanism, demonstrating that aequorin's blue emission stimulates GFP's green light [1]. |

| 1992 | Cloning and sequencing of the GFP gene | Douglas Prasher | Enabled the genetic manipulation of GFP, opening the door for its use as a universal genetic tag [1] [2]. |

| 1994 | Demonstration of GFP as a marker for gene expression in living organisms | Martin Chalfie et al. | Proved GFP could be expressed and would fluoresce in other species, revolutionizing cell biology [1]. |

The discovery process was arduous. Shimomura and his colleagues collected and processed an estimated 850,000 jellyfish over multiple seasons, manually cutting the light-emitting rings from each specimen to obtain a few hundred milligrams of the key proteins [2]. A critical breakthrough came when Shimomura observed that the luminescent material, when washed down a sink with seawater, emitted a bright blue flash. He correctly hypothesized that calcium ions (Ca²⁺) in the seawater triggered the light emission, leading to the identification and naming of the photoprotein aequorin [2]. During the subsequent purification of aequorin using column chromatography, a second, green-colored protein was consistently isolated alongside it. This was the "green protein," later renamed Green Fluorescent Protein [2].

Molecular Mechanism and the FRET Relationship

The bioluminescent system of A. victoria is a two-component process involving a precise intermolecular energy transfer.

The Aequorin-GFP FRET Pathway

In the jellyfish, a mechanical stimulus (e.g., touch) triggers the release of calcium ions within the light organs. Aequorin, a blue-light-emitting photoprotein, binds these Ca²⁺ ions, which catalyzes the oxidation of its bound coelenterazine substrate, resulting in the emission of blue light (~470 nm) [4] [2]. This blue light is not the light we see from the jellyfish. Instead, the energy is non-radiatively transferred to GFP. The GFP chromophore absorbs this energy and re-emits it as lower-energy, green light (~508 nm) [1] [4]. This process is a natural example of Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET).

Principles of FRET

FRET is a mechanism for energy transfer between two light-sensitive molecules (chromophores) based on long-range dipole-dipole interactions [5]. For FRET to occur efficiently, several critical conditions must be met [4] [6] [5]:

- Spectral Overlap: The fluorescence emission spectrum of the donor (aequorin) must significantly overlap with the absorption (excitation) spectrum of the acceptor (GFP). This overlap is quantified by the overlap integral, J.

- Proximity: The donor and acceptor must be in close proximity, typically within 1-10 nanometers. The efficiency of energy transfer (E) is inversely proportional to the sixth power of the distance (r) between the two chromophores: E = 1 / [1 + (r/R₀)⁶], where R₀ is the Förster distance at which efficiency is 50%.

- Orientation: The relative orientation of the donor emission dipole and the acceptor absorption dipole must be favorable, described by the orientation factor, κ² (ranging from 0 for perpendicular to 4 for parallel dipoles).

The aequorin-GFP pair meets all these criteria perfectly, making the energy transfer in the jellyfish highly efficient.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

The study of this system relies on well-established biochemical and biophysical methods.

Protocol 1: Purification of Aequorin and GFP fromA. victoria

This protocol is adapted from the original methods developed by Shimomura [2].

- Objective: To isolate functional aequorin and GFP proteins from jellyfish specimens.

- Materials:

- Live A. victoria jellyfish.

- Homogenization buffer (e.g., low-pH EDTA buffer to chelate Ca²⁺ and prevent aequorin consumption).

- Chromatography equipment (e.g., for gel filtration, ion-exchange).

- Saturated ammonium sulfate solution.

- Procedure:

- Collection and Dissection: Collect live jellyfish and manually dissect the light-emitting rings (tentacles) using scissors.

- Extraction: Homogenize the tissue in a cold, low-pH EDTA buffer. The acidic pH and absence of Ca²⁺ inhibit the luminescent reaction, preserving aequorin.

- Initial Precipitation: Subject the homogenate to ammonium sulfate precipitation. Both aequorin and GFP precipitate at specific saturation levels.

- Chromatographic Separation: Re-dissolve the precipitate and apply to a size-exclusion chromatography column. Aequorin and GFP will elute at different volumes due to their distinct molecular weights, allowing for separation.

- Verification: Test aequorin fractions by adding Ca²⁺ and observing blue luminescence. Verify GFP fractions by exposing to UV or blue light and observing green fluorescence.

Protocol 2:In VitroReconstitution of FRET

This protocol is based on the seminal work of Morise et al. (1974) [1].

- Objective: To demonstrate energy transfer from aequorin to GFP in a controlled cell-free system.

- Materials:

- Purified aequorin and GFP (from Protocol 1 or commercial sources).

- Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) solution.

- Luminometer or spectrofluorometer capable of kinetic measurements.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare two solutions in identical buffers:

- Control: Purified aequorin only.

- Test: Purified aequorin mixed with purified GFP.

- Triggering Luminescence: Rapidly inject a CaCl₂ solution into both the control and test samples to activate aequorin.

- Spectral Measurement: Immediately measure the emission spectrum of the resulting light from both samples using a luminometer.

- Analysis: The control sample (aequorin only) will show a peak emission in the blue spectrum (~470 nm). The test sample (aequorin + GFP) will show a significant decrease in the ~470 nm peak and the appearance of a new, dominant peak in the green spectrum (~508 nm), confirming the occurrence of FRET.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare two solutions in identical buffers:

Quantitative Data and Spectral Properties

The functional characteristics of aequorin and GFP are defined by their specific quantitative parameters.

Table 2: Biophysical and Spectral Properties of Aequorin and GFP from A. victoria

| Parameter | Aequorin | Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) |

|---|---|---|

| Native Function | Ca²⁺-activated blue-light-emitting photoprotein | Accepts energy from aequorin via FRET to emit green light [1] |

| Primary Emission Wavelength | ~470 nm (Blue) | ~508 nm (Green) [1] [4] |

| Key Trigger/Co-factor | Calcium ions (Ca²⁺) | Energy transfer from aequorin (light ~470 nm) [2] |

| Chromophore | Coelenterazine + molecular oxygen (substrate) | 4-(p-hydroxybenzylidene)-imidazolidin-5-one (HBI); formed by autocatalytic cyclization of Ser65-Tyr66-Gly67 [7] [8] |

| Quantum Yield | ~0.15 - 0.20 | Wild-type: ~0.70 - 0.80; Enhanced variants (e.g., EGFP) are higher [4] |

| Molecular Weight | ~21 kDa (apoprotein) | ~27 kDa [8] |

| Critical for FRET | Donor | Acceptor |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research into and applications derived from the aequorin-GFP system utilize a suite of key reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying the Aequorin-GFP System and its Applications

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Aequorin | Purified photoprotein, often from heterologous expression in E. coli. | A highly sensitive biological calcium indicator; emits light upon binding Ca²⁺, used in intracellular calcium imaging and signaling studies [2]. |

| Recombinant GFP & Variants | Purified fluorescent proteins (e.g., wild-type GFP, EGFP, CFP, YFP). | Used as fluorescent tags for protein localization, gene expression reporters, and as the acceptor component in engineered FRET biosensors [4] [8]. |

| Aequorin-GFP Fusion Proteins | Genetically encoded constructs linking aequorin and GFP. | Serves as a model system to study and calibrate FRET efficiency due to their fixed proximity and known orientation [6]. |

| Coelenterazine | The small-molecule luciferin substrate for aequorin. | Required to reconstitute active aequorin; different analogs (e.g., native, h, cp) can modify emission intensity and kinetics [2]. |

| Calcium Buffers/Ionophores | Solutions (e.g., EGTA) and compounds (e.g., A23187) to control extracellular and intracellular Ca²⁺ levels. | Essential for calibrating aequorin-based assays and for experimentally manipulating cellular calcium to trigger the FRET system [2]. |

| Ancestral Resurrected FPs (e.g., QuetzalFP) | Computationally designed fluorescent proteins based on ancestral sequence reconstruction (ASR) [3]. | Provides highly stable and bright platforms for developing novel biosensors and for phylogenetic studies of FP evolution, offering enhanced performance in harsh environments (e.g., in polymers for Bio-HLEDs) [3]. |

The discovery of the A. victoria GFP-aequorin system provided the foundational reference point for a now-expansive field studying the phylogenetic distribution of GFP-like proteins. While GFP was once thought to be a unique oddity, numerous homologous proteins have been discovered in other cnidarians (e.g., corals), and even in distant phyla like chordates [4] [3]. The evolutionary history of these proteins is actively being unraveled. For instance, the origin of bioluminescence in Cnidaria has been estimated at 540 million years ago [3]. Modern techniques like Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) are being used to resurrect putative ancient FPs, such as QuetzalFP, which demonstrate that ancestral proteins can exhibit remarkable stability and brightness, often surpassing their modern counterparts in certain applications [3]. This phylogenetic perspective underscores that the A. victoria system is not merely an isolated biological curiosity, but a single, highly optimized manifestation of a much broader and older protein family. Continued study of this original FRET pair and its diverse analogs is essential for understanding the evolution of biological light and for engineering the next generation of biological tools for research and medicine.

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and its homologs are no longer viewed as curiosities but as critical tools in molecular biology and drug discovery. While initially discovered in the bioluminescent hydrozoan Aequorea victoria, subsequent research has revealed a vast phylogenetic expansion of GFP-like proteins, particularly within non-bioluminescent Anthozoans such as reef-building corals and sea anemones. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the phylogenetic distribution, identification, and characterization of these proteins. We summarize current methodologies for transcriptome assembly and phylogenomic analysis, detail experimental protocols for protein characterization, and visualize key workflows and pathways. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current data and methodologies to facilitate the discovery and application of novel GFP-like proteins, framing these efforts within the broader context of understanding their evolutionary origins and functional diversification.

The discovery of GFP-like proteins in non-bioluminescent Anthozoa species fundamentally altered the perception of their biological function, demonstrating they are not always functionally linked to bioluminescence [9]. This finding opened a new field of research into the diversity and evolutionary history of this protein family. Anthozoans, including corals and sea anemones, possess a remarkable variety of GFP-like proteins, emitting colors across the visible spectrum, from green and yellow to red and far-red [10]. This diversity arises from a series of gene duplications and amino acid substitutions that have fine-tuned the spectral properties of these proteins.

The phylogenetic distribution of GFP-like proteins extends beyond Cnidaria. Homologs have been identified in copepods (arthropods) and cephalochordates (amphioxus), although these are quite distinct from their cnidarian counterparts [11]. The evolutionary origin of this protein family remains an active area of research. One hypothesis suggests a single evolutionary origin, with subsequent loss in many bilaterian lineages, while another posits multiple independent origins or horizontal gene transfer events [12]. The identification of non-fluorescent, GFP-like protein orthologs in ctenophores, which lack key residues for chromophore formation, suggests the ancestral protein may have had a different function [12]. Despite their broad distribution, the most spectacular radiation of GFP-like proteins has occurred in Anthozoa, making them a focal point for phylogenetic and functional studies. The resources developed for non-model anthozoan species, including transcriptomes for corals like Fungia scutaria, Montastraea cavernosa, and Seriatopora hystrix, have made it possible to identify hundreds to thousands of orthologs and clarify uncertainties in the scleractinian phylogeny [13].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and resources for research into Anthozoan GFP-like proteins.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Resources for GFP-like Protein Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function and Application | Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome Databases | Gene discovery and sequence retrieval for non-model organisms. | Searchable databases for anthozoan species (e.g., developed for F. scutaria, M. cavernosa, S. hystrix) [13]. |

| Host Animal rDNA Sequences | Phylogenetic reconstruction of host species to contextualize protein evolution. | 18S-28S rDNA used to build phylogenies for Porites species complexes [14]. |

| Fluorescence Microscopy Systems | In situ observation and documentation of fluorescence patterns. | Systems equipped with royal blue (440–460 nm) and green (510–540 nm) excitation lights with corresponding long-pass filters [15]. |

| Stereomicroscope with Fluorescence Adapter | Standardized imaging of fluorescent traits across multiple specimens. | Leica stereomicroscope with DMC5400 camera and SFA Fluorescence Adapter [15]. |

| Ocean Optics QE65000 Spectrometer | Acquisition of precise fluorescence emission spectra. | Used with a bifurcated fiber optics cable for spectral analysis of fluorescence [15]. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software | Inferring evolutionary relationships among GFP-like protein sequences. | Software for phylogenetic inference using orthologous sequences identified from transcriptomes [13]. |

Methodologies for Phylogenomic Analysis and Identification

Transcriptome Sequencing and Assembly

Identifying novel GFP-like proteins begins with generating comprehensive genetic resources for the target organisms.

- Sample Collection and RNA Extraction: Collect fresh tissue samples from the target anthozoan species, ensuring representation of different life stages, symbiotic states, or environmental conditions. Immediately preserve tissue in RNAlater Stabilization Solution. Extract total RNA using kits such as the RNeasy Mini Kit, which is effective for corals like Seriatopora hystrix and Fungia scutaria larvae [13].

- cDNA Library Preparation and Sequencing: Use high-throughput sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina HiSeq) to generate deep transcriptome data. The preparation of cDNA libraries and sequencing to produce ~20–30 million reads per sample provides sufficient coverage for robust de novo assembly [13].

- De Novo Transcriptome Assembly: Assemble the sequenced reads de novo using appropriate software. This process typically produces ~75,000–110,000 transcripts per sample. Assess assembly quality using metrics like mean transcript length (~1.4 kb) and N50 value (~2 kb), which should be comparable to the distribution of gene models from a sequenced coral genome like Acropora digitifera [13]. A successful assembly should include matches for more than half of the gene models from a reference genome and contain many reasonably complete transcripts.

Identifying Orthologs and Phylogenetic Inference

Once a transcriptome is assembled, the next step is to identify GFP-like proteins and their evolutionary relationships.

- Ortholog Identification: Recover sequences for genes of interest from the assembled transcriptomes using searchable databases. Identify orthologous sequences across species by searching for GFP-like protein domains. This allows for the construction of datasets comprising hundreds to thousands of orthologs from diverse scleractinian species and related taxa [13].

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Perform phylogenetic inference using the identified orthologous sequences. Employ maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods to reconstruct relationships. This approach has been shown to recover known phylogenetic relationships and demonstrate superior performance over trees constructed using single mitochondrial loci, thus clarifying substantial uncertainties in the existing scleractinian phylogeny [13].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for the phylogenetic identification of GFP-like proteins.

Experimental Protocols for Functional Characterization

Fluorescence Imaging and Pattern Analysis

Characterizing the phenotypic expression of GFP-like proteins is crucial for hypothesizing their function.

- In Situ Fluorescence Photography: In the field or laboratory, use a camera equipped with a macro lens, a yellow barrier filter (e.g., #12 Screw-In Filter), and blue excitation light sources (e.g., SOLA Nightsea Light) to photograph fluorescence in living specimens [15]. Adjust white balance across various depths when capturing images under natural lighting conditions to accurately represent colors.

- Standardized Laboratory Imaging: For a trait-based analysis, image fixed specimens 1–10 days post-fixation in ethanol to prevent interference from algal chlorophyll fluorescence. Use a stereomicroscope (e.g., Leica 205A) equipped with a fluorescence adapter and a high-resolution camera. Take images in brightfield and under fluorescence using royal blue and green excitation lights with corresponding long-pass filters. Keep exposure time, gain, and excitation intensity consistent across specimens to maximize the dynamic range and allow for comparisons [15].

- Fluorescent Trait Analysis: Based on the fluorescent images, record the presence or absence of fluorescence for defined body parts. To quantify the expression, use image analysis software like ImageJ. Outline the relevant body parts (e.g., dorsal carapace, antennular peduncle) to measure the total area. Subsequently, apply the threshold function to determine the fluorescent area within that region. Calculate the proportion of fluorescent area by dividing the fluorescent area by the total area [15]. This multivariate approach allows for the identification of distinct fluorescent morphologies (fluotypes).

Spectrometric Characterization

Determining the spectral properties of the fluorescent proteins is essential for their classification and potential application.

- Equipment Setup: Use a fluorescence spectrometer (e.g., Ocean Optics QE65000) with a bifurcated fiber optics cable. Excitation light can be generated using lasers of specific wavelengths (e.g., a green laser for red fluorescence excitation) [15].

- Measurement Protocol: Position the fiber optic probe to excite the sample and collect the emitted light. For a full spectral analysis, measure the emission spectrum across a range of wavelengths. Compare the obtained spectra to known standards to characterize the fluorescent protein's emission profile [11]. This is critical for distinguishing between different types of GFP-like proteins, such as GFPs, RFPs, and CFPs.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics from De Novo Transcriptome Assemblies in Anthozoa [13]

| Species | Number of Sequence Reads | Number of Assembled Transcripts | Mean Transcript Length | N50 | A. digitifera Gene Models Matched |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungia scutaria | ~20-30 million | ~75,000-110,000 | ~1.4 kb | ~2.0 kb | 54-67% |

| Montastraea cavernosa | ~20-30 million | ~75,000-110,000 | ~1.4 kb | ~2.0 kb | 54-67% |

| Seriatopora hystrix | ~20-30 million | ~75,000-110,000 | ~1.4 kb | ~2.0 kb | 54-67% |

| Anthopleura elegantissima | ~20-30 million | ~75,000-110,000 | ~1.4 kb | ~2.0 kb | 54-67% |

Diverse Functions and Ecological Significance

GFP-like proteins in Anthozoa are not merely structural curiosities; they serve a range of proposed functional roles that contribute to the fitness of the holobiont. The diagram below summarizes how these functions interact with environmental factors.

The functional roles are supported by specific evidence:

- Photoprotection: In shallow waters with high light intensity, GFP-like proteins can act as a sunscreen by absorbing high-energy photons and dissipating them as harmless fluorescent light or heat, thereby protecting the symbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodiniaceae) from photoinhibition [14].

- Prey Attraction: The "light trap" hypothesis proposes that in mesophotic (low-light) environments, GFP conversion of blue light to green fluorescence can lure planktonic prey, increasing the host's heterotrophic capacity [14] [15].

- Symbiosis Modulation: Red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) may play a role in attracting specific strains of Symbiodiniaceae to the host cnidarian, facilitating the establishment of symbiosis [14]. Furthermore, GFP-like proteins may fine-tune the internal light environment to optimize photosynthesis by the symbionts [15].

- Antioxidant Activity: Both GFPs and RFPs have demonstrated the ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and superoxide radicals, which are particularly generated during thermal stress and can lead to coral bleaching [14].

- Visual Signaling: The targeted expression of fluorescent proteins in specific anatomical regions (e.g., tentacle tips, oral discs) may provide visual cues for conspecific communication or other interspecific interactions [14].

Notably, the expression and distribution of these proteins are dynamic. Under thermal stress, fluorescence patterns can reorganize, with proteins spreading uniformly across the tissue, suggesting their potential use as a non-invasive biomarker for assessing coral health [14].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

The unique properties of Anthozoa-derived fluorescent proteins have made them indispensable tools in biomedical research and drug discovery, extending their utility far beyond their native ecological roles.

- Multi-Color Imaging and Cell Labeling: Anthozoa proteins are available in colors and properties unlike those of A. victoria GFP variants, providing a powerful palette for multiplexed imaging. Proteins such as the monomeric red and dimeric far-red fluorescent proteins enable simultaneous tracking of multiple molecular targets or cellular processes [10].

- Biosensors and FRET Applications: GFP-like proteins can be engineered into biosensors to detect changes in cellular conditions, such as pH, calcium levels, and enzyme activity. Furthermore, they are central to Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) assays, which are used to study protein-protein interactions, receptor dimerization, and oligomerization in live cells [16].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): The stability and detectability of these proteins allow for the development of genetically engineered cell lines with GFP expression under the control of specific promoters. These cells are valuable for automated analysis and can be adapted for HTS systems to identify new chemical entities that modulate receptor activity or other therapeutic targets [16].

- Lineage Tracing and In Vivo Imaging: Fluorescent proteins from Anthozoa have been used to create "rainbow" mice, where different cell types express distinct colors, allowing for the fate mapping of stem cells and the study of development and disease progression in real-time [16]. Their use as nontoxic, genetically encodable markers avoids staining procedures and hazardous radiolabeled binding assays.

The phylogenetic expansion of GFP-like proteins in non-bioluminescent Anthozoa represents a remarkable example of molecular evolution and functional diversification. Through the application of transcriptomics, phylogenomics, and detailed phenotypic characterization, researchers can systematically identify and characterize novel proteins within this family. The resulting diverse palette of fluorophores has not only advanced our understanding of coral biology and resilience but has also provided the biomedical research community with an array of powerful tools. As sequencing technologies and functional genomic techniques continue to advance, the discovery of new GFP-like proteins with novel properties is poised to continue, further illuminating the evolutionary history of this protein family and unlocking new applications in drug discovery and cellular imaging.

Proteins homologous to the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria constitute a diverse family responsible for the spectacular colors observed in reef-building corals and other anthozoans [17] [18]. These GFP-like proteins are major color determinants in reef Anthozoa, accounting for practically every visible coral color other than the brown pigmentation of photosynthetic symbionts [18]. Unlike the bioluminescent function of GFP in jellyfish, where it converts blue light emitted by aequorin to green light, GFP-like proteins in non-bioluminescent Anthozoa are thought to serve ecological functions including photoprotection, prey capture, and optimization of the light environment for symbiotic algae [14] [19] [20].

The family exhibits remarkable diversity, with proteins emitting colors across the visible spectrum and including both fluorescent and non-fluorescent members [17] [18]. This diversity arises from variations in the chromophore structure and its protein environment, which are products of autocatalytic reactions within the protein sequence itself [17]. The phylogenetic distribution and evolution of these proteins across Zoantharia and other coral groups provide insights into both molecular evolutionary processes and the ecological adaptations of reef-building organisms.

Classification and Phylogenetic Distribution

Major Color Classes and Chromophore Types

GFP-like proteins from Anthozoa are classified into several distinct color classes based on their spectral properties. The table below summarizes the fundamental classification of these proteins.

Table 1: Major Color Classes of Anthozoan GFP-like Proteins

| Color Class | Spectral Characteristics | Chromophore Type | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyan (CFP) | Excitation: 440-460 nm; Emission: 485-495 nm | GFP-type | scubGFP1, scubGFP2 [17] |

| Green (GFP) | Excitation peaks: ~395 nm, ~475 nm; Emission: ~510 nm | GFP-type | cgigGFP, hcriGFP [17] |

| Yellow (YFP) | Emission between green and red | Variants of GFP-type | zoanYFP [21] |

| Red (RFP) | Excitation: 550-580 nm; Emission: 580-610 nm | DsRed-type or Kaede-type | DsRed, mcavRFP [17] [22] |

| Chromoprotein (CP) | Non-fluorescent, strong absorption | Isomerized DsRed-type | Various purple-blue proteins [18] |

The chromophore diversity underpins this color variation. While cyan and green fluorescent proteins share the same chromophore structure, red fluorescent proteins and chromoproteins feature extended chromophore structures with additional conjugation achieved through different autocatalytic pathways [18]. The Kaede-type red fluorescent proteins, characteristic of corals in the Faviina suborder, exhibit a distinctive narrow orange-red fluorescence with a characteristic shoulder at 630 nm in the emission spectrum, unlike the broader emission of DsRed-type proteins [22] [18].

Phylogenetic Distribution Across Coral Taxa

Molecular phylogenetic analyses reveal that GFP-like proteins from Zoantharia and other corals fall into multiple evolutionary clades, with complex relationships between protein color and taxonomic origin.

Table 2: Phylogenetic Distribution of GFP-like Proteins in Coral Taxa

| Coral Group | GFP-like Protein Lineages | Color Diversity | Evolutionary Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zoantharia | At least four distinct clades [17] | Multiple colors per clade | Recent color conversion events; balancing selection [17] [23] |

| Scleractinia (reef-building corals) | Three major paralogous lineages [18] | Full color complement (cyan, green, red, purple-blue) | One lineage retained in all families; others underwent sorting between groups [18] |

| Faviina | Specialized Kaede-type red proteins [22] | Green ancestral, red derived | ~12 mutations required for green-to-red transition with epistatic interactions [22] |

| Porites species | Multiple fluorescence patterns [14] | Green and red fluorescence | Pattern variation within single lineages; thermal stress response [14] |

The phylogenetic distribution demonstrates that each major coral group possesses multiple GFP-like protein lineages, and that similar colors have evolved independently in different taxonomic groups through convergent or parallel evolution [17] [18]. Proteins of different colors within the same clade indicate that color conversion has occurred multiple times throughout evolutionary history [17]. The common ancestor of all coral fluorescent proteins has been reconstructed as a green fluorescent protein, suggesting that the extensive color diversity observed today originated from this ancestral state [18].

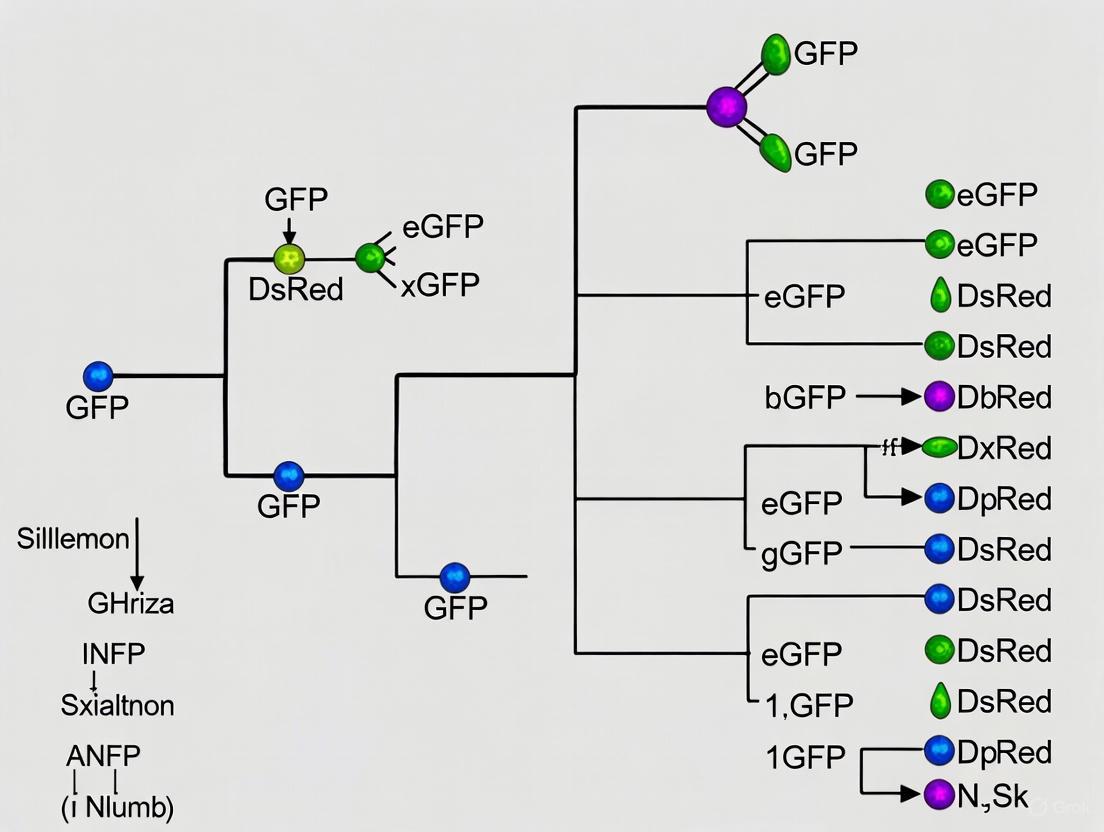

Figure 1: Evolutionary pathways of GFP-like proteins from an ancestral green state to diverse color classes through different molecular mechanisms. The diagram shows the multiple independent origins of similar colors across different coral taxa.

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Protein Identification and Cloning

The standard methodology for identifying and characterizing novel GFP-like proteins involves a multi-step process combining molecular biology and spectroscopic techniques [17]. The following workflow outlines the key experimental stages:

Figure 2: Standard experimental workflow for identification and characterization of novel GFP-like proteins from coral samples, combining molecular and spectroscopic approaches.

Sample Collection and Preparation: Coral tissue samples (100-500 mg) are collected, typically during night dives to minimize solar radiation effects [17]. Candidate specimens may be pre-screened using UV flashlights to identify fluorescent phenotypes [17].

Molecular Cloning: Total RNA is isolated from tissue samples and reverse-transcribed to cDNA [17]. Degenerate primers targeting conserved regions of GFP-like proteins are used to amplify coding sequences, which are then cloned into expression vectors such as pGEM-T for transformation into E. coli hosts [17] [22].

Screening and Expression: Transformed bacterial colonies are screened for fluorescence using fluorescence microscopy [17]. Selected colonies are harvested, and proteins are expressed for spectral characterization. For some red fluorescent proteins with "timer" phenotypes (e.g., zoan2RFP, mcavRFP), maturation requires extended incubation periods or specific light exposure [17] [22].

Evolutionary Analysis Using Ancestral Protein Reconstruction

To understand the evolutionary transitions between color classes, researchers have employed ancestral protein reconstruction to resurrect and characterize putative ancestral GFP-like proteins [22] [18]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying mutations responsible for functional changes that may be obscured in extant proteins due to subsequent specialization.

The methodology involves:

- Sequence Alignment and Phylogeny: Comprehensive multiple sequence alignment of GFP-like proteins from diverse coral taxa [17] [18].

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: Probabilistic methods to infer the most likely sequences of ancestral nodes in the phylogeny [22] [18].

- Combinatorial Library Synthesis: Creating libraries of genes representing possible evolutionary intermediates between ancestral and extant proteins [22].

- Functional Screening: Expressing these libraries in bacterial systems and screening for spectral phenotypes [22].

This approach was successfully applied to study the evolution of Kaede-like red fluorescent proteins in the Faviina suborder, revealing that approximately 12 mutations were required for the transition from green to red fluorescence, with significant epistatic interactions between sites [22].

Functional Assays for Ecological Roles

To determine the ecological functions of GFP-like proteins, researchers have developed experimental protocols to test specific hypotheses:

Photoprotection Assays: Corals with different fluorescent protein expression levels are exposed to varying light conditions, particularly blue light matching the absorption spectra of their pigments [23]. Measurements of photodamage (e.g., photosystem II efficiency in symbiotic algae), oxidative stress markers, and coral growth rates quantify photoprotective effects [23].

Thermal Stress Response: Fluorescence patterns are monitored during controlled thermal stress experiments to assess potential roles as stress biomarkers [14]. The redistribution of fluorescence to uniform patterning under thermal stress suggests fluorescent proteins may provide non-invasive indicators of coral health [14].

Symbolnt Performance Metrics: The relationship between fluorescent protein expression and photosynthetic efficiency of symbiotic algae is assessed using pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometry to measure quantum yield of photosystem II under different light conditions [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GFP-like Protein Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pGEM-T vector | Cloning and initial expression in E. coli | [17] [22] |

| Bacterial Host Strains | E. coli JM109, Top10 | Heterologous protein expression | [17] [22] |

| Fluorescence Microscopy Systems | Leica MZ FL III with filter sets | Colony screening and phenotypic analysis | [22] |

| Spectrofluorometers | LS-50B (Perkin-Elmer) | Spectral characterization of fluorescent proteins | [17] |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | SMART cDNA amplification kit | cDNA library construction from coral RNA | [17] |

| Specialized Filter Sets | Double-bandpass filters (e.g., Chroma #51004v2) | Simultaneous visualization of multiple fluorophores | [22] |

| Photoactivation Equipment | UV-A light sources ("blacklight") | Inducing chromophore maturation in Kaede-type proteins | [22] |

The classification of GFP-like proteins from Zoantharia and other corals reveals a complex evolutionary history characterized by multiple parallel evolution of color diversity, frequent color conversion events, and lineage-specific diversification [17] [18]. The phylogenetic distribution patterns demonstrate that similar colors have arisen independently in different taxonomic groups, suggesting strong ecological pressures shaping the evolution of these proteins [17] [23].

Future research directions include more comprehensive sampling across coral taxa, functional characterization of the ecological roles of different color morphs in natural environments, and exploitation of the diverse molecular properties of these proteins for biotechnology applications [14] [24]. The experimental methodologies outlined here provide a framework for systematic analysis of GFP-like protein diversity, evolution, and function, contributing to both basic scientific knowledge and applied biotechnological development.

The discovery and subsequent development of fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized biological imaging, providing researchers with a versatile genetic toolkit for visualizing dynamic processes within living cells and organisms. This family of proteins, homologues of the original Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria, spans virtually the entire visible spectrum through natural diversity and protein engineering [25] [26]. The phylogenetic distribution of GFP-like proteins extends beyond cnidarians to include copepods and cephalochordates (amphioxus), suggesting multiple evolutionary paths including potential horizontal gene transfer events or inheritance from a common bilaterian ancestor [11]. The structural basis for this remarkable spectroscopic diversity lies in a conserved β-can fold that protects an autocatalytically formed chromophore, with spectral tuning achieved through transformations including posttranslational modifications, chromophore isomerization, and rearrangements of the surrounding amino acid environment [27].

Understanding the relationship between protein structure and spectral properties has been fundamental to expanding the FP palette. The physical extent of π-orbital conjugation within the chromophore largely determines the general spectral class, while local environmental variables such as charged residue positioning, hydrogen bonding networks, and hydrophobic interactions can produce spectral shifts of up to 20 nm in absorption and emission maxima [26]. This review examines the natural diversity of fluorescent proteins across phylogenetic lineages, their structural determinants of fluorescence, and their emerging applications as biomarkers for environmental stress and biological activity.

Structural Basis of Spectral Diversity in GFP-like Proteins

The Conserved β-Barrel Architecture and Chromophore Formation

All GFP-like proteins share a highly conserved structural motif: an 11-stranded β-barrel surrounding a central α-helix that contains the chromophore-forming tripeptide [28] [29]. This robust structure, approximately 25Å in diameter and 40Å tall, serves as a protective scaffold that isolates the chromophore from the external environment, enabling fluorescence by restraining the chromophore and preventing nonradiative decay pathways [28]. The β-barrel fold is so unique that GFP forms its own protein class with no other known proteins sharing this structure [11].

The fluorescence originates from a mature chromophore formed through autocatalytic cyclization of a tripeptide sequence (Ser65-Tyr66-Gly67 in A. victoria GFP) [29]. This maturation process involves a series of aerobic biochemical steps: folding, cyclization, oxidation, and dehydration, resulting in the formation of 4-hydroxybenzylidene-imidazolinone (HBI) [29]. The process begins with nucleophilic attack by the amide nitrogen of Gly67 on the carbonyl carbon of Ser65, forming an imidazolin-5-one heterocyclic ring. Oxidation by molecular oxygen then extends electron conjugation of the imidazoline ring system to include the aromatic substituent, creating a conjugated π-system that can absorb and emit visible light [26]. Remarkably, this entire process occurs without enzymatic assistance, relying only on molecular oxygen [29].

Molecular Mechanisms of Spectral Tuning

The spectral diversity of GFP-like proteins arises from modifications to the chromophore structure and its chemical environment within the protective β-barrel. Four primary mechanisms govern spectral tuning across the FP palette:

Chromophore Chemical Identity: Substitutions at the tyrosine residue (position 66 in A. victoria GFP) alter the fundamental electronic properties of the chromophore. The Y66H mutation produces Blue Fluorescent Proteins (BFP) with excitation at ~380 nm and emission at 448 nm, while the Y66W mutation creates Cyan Fluorescent Proteins (CFP) with excitation at ~436 nm and emission at 485 nm [26].

π-Orbital Conjugation Extent: The physical extent of π-orbital conjugation within the chromophore largely determines the general spectral class. Extended conjugation systems, such as those found in red fluorescent proteins, result in longer wavelength absorption and emission [26].

Chromophore Isomerization and Planarity: The chromophore can exist in different isomeric forms (cis vs. trans) with varying degrees of planarity. In GFP, the chromophore is cis and approximately planar, while other FPs like eqFP611 contain the trans isomer [28]. The degree of planarity enforced by the surrounding protein matrix affects the energy gap between ground and excited states, thereby influencing emission wavelength.

Environmental Perturbations: Charged amino acid residues, hydrogen bonding networks, and hydrophobic interactions in the chromophore vicinity can produce spectral shifts up to 20 nm [26]. For example, in Yellow Fluorescent Proteins (YFP), the T203Y mutation creates π-electron stacking interactions between the substituted tyrosine and the chromophore, resulting in red-shifted excitation and emission [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Chromophore Variants and Their Spectral Properties

| Chromophore Type | Amino Acid Substitutions | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFP (Green) | None (wild-type) | 395 (major), 475 (minor) | 509 | Ser65-Tyr66-Gly66, neutral and anionic states |

| BFP (Blue) | Y66H | ~380 | ~448 | Histidine at position 66 |

| CFP (Cyan) | Y66W | ~436 | ~485 | Tryptophan at position 66 |

| YFP (Yellow) | T203Y | ~514 | ~527 | π-stacking with chromophore |

| RFP (Red) | Various | ~558 | ~583 | Extended conjugation, acylimine |

The chromophore can exist in different protonation states, leading to complex photophysical behavior. In wild-type GFP, the chromophore exhibits two excitation maxima at approximately 395 nm (neutral form) and 475 nm (anionic form), with both states emitting green fluorescence around 509 nm [29]. The mechanism for green emission upon ultraviolet excitation involves excited-state proton transfer (ESPT), where the excited protonated chromophore (A) transfers a proton to form an anionic excited state (I) that emits a green photon [28]. This intricate photocycle involves multiple excited-state intermediates and ground states, demonstrating the dynamic nature of FP chromophores [28].

Phylogenetic Distribution and Natural Diversity of Fluorescent Proteins

Evolutionary Origins Across Distant Taxa

GFP-like proteins display a remarkably patchy phylogenetic distribution across distantly related organisms. The initial discovery of GFP in the cnidarian Aequorea victoria has been followed by identifications in other cnidarians (corals and sea anemones), copepods, and cephalochordates (amphioxus) [11]. This sporadic distribution across deep evolutionary lineages presents a conundrum regarding the evolutionary history of GFP-like proteins—whether they were inherited from a common ancestor or acquired through horizontal gene transfer events.

Research on cephalochordates provides particular insight into this question. Studies of Asymmetron lucayanum, an early-diverged cephalochordate lineage, revealed two GFP-encoding genes closely related to those in the genus Branchiostoma, indicating that GFP genes were likely present in ancestral cephalochordates rather than recently acquired through horizontal transfer [11]. Fluorescence in A. lucayanum appears diffusely throughout the body with particular intensity in ripe ovaries, exhibiting an emission peak at 525 nm when excited at 470 nm [11]. The genus Branchiostoma has undergone lineage-specific expansion of GFP-encoding genes, largely driven by tandem duplications, with strong purifying selection shaping their evolution [11].

Functional Diversity in Natural Environments

In marine organisms, GFP-like proteins serve diverse ecological functions that extend beyond mere coloration. In reef-building corals, FPs serve functional roles including photoprotection, prey capture, and algal symbiont attraction [14]. The specific distribution patterns of FPs within coral colonies—such as highlighted (concentrated in oral regions or tentacles), uniform, or complementary (non-overlapping GFP and RFP patterns)—suggest specialized functional adaptations [14].

The functional versatility of GFP-like proteins is particularly evident in corals of the genus Porites. Studies of Porites cf. lutea and Porites cf. lobata from the Great Barrier Reef identified six distinct fluorescence patterns: star, uniform, absent, tentacles, oral region, and tentacle tips [14]. These patterns are shared by all polyps in a colony and can reorganize under thermal stress, suggesting FPs may provide biomarkers of environmental stress [14]. The reorganization of both green and red fluorescence to uniform patterning during thermal stress indicates these proteins may play adaptive roles in stress response, possibly through antioxidant functions [14].

Table 2: Natural Fluorescent Protein Distribution and Proposed Functions

| Organism Group | Representative Species | FP Colors | Proposed Natural Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cnidarians | Aequorea victoria (jellyfish) | Green | Energy transfer from aequorin [25] |

| Cnidarians | Porites corals (GBR) | Green, Red | Photoprotection, prey capture, symbiont attraction, stress response [14] |

| Cephalochordates | Branchiostoma floridae (amphioxus) | Green | Unknown, potentially photoprotection [11] |

| Cephalochordates | Asymmetron lucayanum (amphioxus) | Green | Unknown, intense in ovaries [11] |

| Anthozoans | Discosoma striata (sea anemone) | Red | Unknown, ecological interactions [26] |

The Expanded Fluorescent Protein Color Palette

Engineering the Blue to Yellow Spectrum

Protein engineering of A. victoria GFP has generated a suite of blue to yellow fluorescent variants through systematic mutagenesis. The first major improvement was the S65T mutation, which dramatically improved spectral characteristics by increasing fluorescence, photostability, and shifting the major excitation peak to 488 nm while keeping emission at 509 nm [25]. This mutation matched the spectral characteristics of commonly available FITC filter sets, greatly enhancing practical utility [25]. Additional folding improvements at 37°C (F64L mutation) created Enhanced GFP (EGFP), enabling practical use in mammalian cells [30].

Further engineering efforts produced:

- Blue Fluorescent Proteins (BFP): Created through the Y66H substitution, resulting in excitation at ~380 nm and emission at 448 nm [26]. Despite additional mutations to improve folding and expression, BFP variants remain limited by low quantum yields, rapid photobleaching, and the need for ultraviolet excitation, which is phototoxic to cells and hampered by cellular autofluorescence [26].

- Cyan Fluorescent Proteins (CFP): Derived from the Y66W mutation, yielding excitation at ~436 nm and emission at 485 nm [26]. Enhanced variants like Cerulean feature higher extinction coefficients, improved quantum yields, and single-exponential fluorescence lifetime decay, making them particularly useful for FRET experiments and lifetime imaging [26].

- Yellow Fluorescent Proteins (YFP): Generated through the T203Y mutation, which creates π-stacking interactions that red-shift excitation to ~514 nm and emission to ~527 nm [26]. Further refinements produced variants like Venus and Citrine with improved folding and pH stability [26].

Red and Far-Red Fluorescent Proteins from Anthozoans

The discovery of DsRed from the sea anemone Discosoma striata opened the spectral range to longer wavelengths, providing essential tools for multicolor imaging and biological applications where reduced autofluorescence and deeper tissue penetration are advantageous [26]. The DsRed chromophore forms through an additional oxidation step that extends the conjugation system, creating a planar cis configuration that absorbs at ~558 nm and emits at ~583 nm [26].

Unlike A. victoria GFP variants, which predominantly form weak dimers, early DsRed variants formed obligate tetramers, limiting their utility as fusion tags. Extensive engineering produced monomeric red fluorescent proteins (mFruit series) including mCherry, mStrawberry, and mPlum, which exhibit progressively longer emission wavelengths while maintaining monomeric character [26]. Structural studies of Anthozoan FPs reveal at least three distinct chromophore motifs: planar cis (found in DsRed), planar trans (characteristic of eqFP611), and non-planar trans (found in the non-fluorescent chromoprotein Rtms5) [26].

Table 3: Engineered Fluorescent Protein Variants and Spectral Characteristics

| Protein | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Brightness (Relative to EGFP) | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBFP | 380 | 448 | 29,000 | 0.31 | ~25% | Weak dimer |

| ECFP | 434 | 477 | 32,500 | 0.40 | ~40% | Weak dimer |

| Cerulean | 433 | 475 | 43,000 | 0.62 | ~79% | Monomeric |

| EGFP | 488 | 507 | 55,000 | 0.60 | 100% | Weak dimer |

| EYFP | 514 | 527 | 83,400 | 0.61 | ~151% | Weak dimer |

| Venus | 515 | 528 | 92,200 | 0.57 | ~158% | Monomeric |

| mCherry | 587 | 610 | 72,000 | 0.22 | ~47% | Monomeric |

Experimental Methodologies for FP Characterization

Spectral Measurement Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of fluorescent proteins requires multiple spectroscopic approaches to fully understand their photophysical properties. Key methodologies include:

One-Photon Excitation Spectroscopy: Conventional measurement of absorption and emission spectra using ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry and fluorometry. This technique identifies major excitation peaks and corresponding emission maxima, providing fundamental characterization of FP spectral properties [31].

Two-Photon Excitation Spectroscopy: This technique involves simultaneous absorption of two longer-wavelength photons (typically in the near-infrared range) to excite the fluorophore. Studies of ECFP, EGFP, and EYFP have demonstrated that two-photon excitation spectra are more differentiated than their one-photon counterparts, exhibiting more pronounced main and local maxima between 820-1150 nm excitation [31]. Two-photon and one-photon emission spectra are identical, indicating both excitation routes lead to the same excited states [31].

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM): Measures the exponential decay rate of fluorescence emission after pulsed excitation, providing information about the fluorophore microenvironment that is independent of concentration. Cerulean exhibits a single-exponential lifetime decay, making it particularly valuable for FRET investigations and lifetime-based sensing [26].

Crystallographic Studies: X-ray diffraction of FP crystals reveals atomic-level details of chromophore conformation and interactions with surrounding amino acids. The first GFP crystal structures provided vital insights into chromophore formation and neighboring residue interactions, enabling rational engineering of improved variants [25].

Coral Fluorescence Pattern Analysis Methodology

Research on fluorescence patterns in corals employs specific methodological approaches:

Coral Collection and Maintenance: Studies typically involve collection of coral colonies from natural reef environments (e.g., Davies Reef in the Great Barrier Reef for Porites species) with maintenance in controlled aquarium systems [14].

Excitation and Emission Imaging: Coral colonies are examined under blue (~470 nm) and green excitation light using specialized imaging systems with appropriate emission filters to detect green and red fluorescence patterns [14].

Phylogenetic Analysis: Host animal phylogeny is constructed using molecular markers such as 18S-28S rDNA sequences to correlate fluorescence patterns with genetic lineages [14].

Stress Response Monitoring: Experimental thermal stress exposure with subsequent fluorescence monitoring to assess FP reorganization under controlled conditions [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescent Protein Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| EGFP (Enhanced GFP) | Standard green fluorescent reference protein | Ex/Em: 488/507 nm, ε: 55,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹, QY: 0.60 [30] |

| Cerulean | Optimized cyan variant for FRET studies | Ex/Em: 433/475 nm, bright variant with single-exponential decay [26] |

| mCherry | Monomeric red fluorescent protein | Ex/Em: 587/610 nm, monomeric, photostable [26] |

| Two-Photon Microscopy System | Deep tissue imaging and spectral characterization | Tunable IR laser (820-1150 nm), high-sensitivity detectors [31] |

| FRET Filter Sets | Biosensor development and protein interaction studies | CFP excitation: 430-450 nm, YFP emission: 525-550 nm [26] |

| Spectrofluorometer | Precise spectral measurements | Dual monochromators, temperature control, polarization capability |

| Protein Purification System | Recombinant FP isolation and purification | Affinity chromatography (His-tag), size exclusion columns |

Emerging Applications and Future Perspectives

Environmental Stress Biomarkers

The reorganization of fluorescence patterns in corals under thermal stress suggests FPs may serve as non-invasive biomarkers for reef health assessment. Studies of Porites corals demonstrate that both green and red fluorescence redistribute to uniform patterning during thermal stress, providing a potential early warning system for coral bleaching events [14]. This fluorescence screening approach offers advantages of being non-invasive and potentially deployable for large-scale reef monitoring.

Advanced Biosensor Development

The expanding FP palette enables engineering of sophisticated biosensors for monitoring cellular processes:

- FRET-Based Biosensors: Pairs like ECFP-EYFP and Cerulean-Venus enable detection of protease activity, calcium signaling, and protein-protein interactions through changes in FRET efficiency [26].

- Redox Sensors: Redox-sensitive GFPs (roGFP) with introduced cysteine residues respond to changing cellular redox states through alterations in fluorescent properties [25].

- pH Sensors: pH-sensitive mutants (pHluorins) exploit the rapid pH change upon synaptic vesicle fusion to visualize neuronal activity [25].

Future Research Directions

The future of fluorescent protein research includes several promising directions:

- Near-Infrared FPs: Engineering FPs with emission in the near-infrared range for improved tissue penetration and reduced autofluorescence in mammalian imaging.

- Improved Photostability: Developing variants resistant to photobleaching for long-term time-lapse studies.

- Advanced Chromophore Chemistry: Exploring non-natural amino acids and novel chromophore structures to expand spectral range and functionality.

- Computational Design: Using molecular dynamics and machine learning to predict and design FPs with desired properties before experimental testing.

The continuing expansion of the fluorescent protein palette, coupled with deeper understanding of phylogenetic distribution and structure-function relationships, ensures these remarkable molecular tools will remain indispensable for biological discovery and innovation.

The remarkable diversity of colors within the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) family serves as a powerful model system for studying molecular evolution. This whitepaper examines the evolutionary forces driving color conversion in GFP-like proteins, with a specific focus on the balance between mutation pressure and natural selection. Framed within the context of the phylogenetic distribution of GFP analogs, we synthesize evidence from cnidarians and cephalochordates to elucidate the mechanisms behind spectral diversification. The discussion is supported by quantitative spectral data, detailed experimental methodologies for characterizing new GFP variants, and bioinformatics approaches for phylogenetic analysis. This resource provides life science researchers and drug development professionals with a technical guide to the evolutionary principles governing functional protein diversity.

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and its homologs constitute a protein family with a unique, evolutionarily conserved β-can structure that enables autocatalytic chromophore formation [25]. While originally discovered in the cnidarian Aequorea victoria, GFP-like proteins have since been identified in diverse organisms including corals, sea anemones, copepods, and cephalochordates [32] [25]. This sporadic phylogenetic distribution across distantly related taxa has prompted ongoing investigation into the evolutionary origins of these proteins, with hypotheses ranging from repeated horizontal gene transfer events to inheritance from a common bilaterian ancestor [32].

The family exhibits striking functional diversity, encompassing proteins that fluoresce across the visible spectrum (cyan to red) as well as non-fluorescent chromoproteins that absorb visible light [33] [17]. In reef-building corals, GFP-like proteins are considered major determinants of coloration, potentially fulfilling roles in photoprotection, photoreception, and antioxidant activity [34]. The evolution of this color diversity presents a compelling evolutionary puzzle: how do proteins with highly similar structures acquire distinct spectral properties, and what selective forces maintain this diversity?

Evolutionary Mechanisms of Color Conversion

The Interplay of Mutation Pressure and Natural Selection

Research on GFP-like proteins from reef Anthozoa provides direct insight into the evolutionary mechanisms driving color diversification. Phylogenetic analysis of these proteins reveals that they fall into several distinct clades, with each clade containing proteins of more than one emission color [33] [17]. This topological pattern suggests multiple independent events of color conversion throughout evolutionary history rather than a simple linear progression of color changes.

The current evolutionary model proposes that the phylogenetic pattern and color diversity in reef Anthozoa results from a balance between selection for GFP-like proteins of particular colors and mutation pressure driving the color conversions [33] [17]. In this framework:

- Natural selection acts to preserve colors that provide adaptive advantages in specific ecological contexts, such as photoprotection in high-light environments or camouflage against predators.

- Mutation pressure continuously introduces genetic variations that can alter chromophore environment and chemistry, thereby driving color conversions even in the absence of immediate selective advantage.

This model explains the observed phylogenetic distribution where different chromophore structures appear as alternative products synthesized within similar autocatalytic environments, with selection and mutation pressure acting as opposing forces determining the prevalence of specific spectral variants [17].

Functional Diversification in Cephalochordates

Further evidence for evolutionary diversification comes from cephalochordates (amphioxus), which encode the largest known family of GFP-like proteins [34]. The amphioxus Branchiostoma floridae possesses 16 GFP-like genes that have diversified into distinct functional classes with differences in fluorescence intensity, extinction coefficients, and absorption profiles [34]. Some members exhibit antioxidant capacity, suggesting functional diversification beyond light-based functions.

Ka/Ks ratios for all amphioxus GFPs are less than one, indicating they continue to be under purifying selection despite their diversification, though with apparent relaxation for highly duplicated clades [32] [34]. This expansion appears to be largely driven by tandem duplications, with the high sequence similarities between different clades providing a model system to map sequence variation to functional changes [34].

Quantitative Analysis of GFP Spectral Diversity

Spectral Characteristics Across Taxa

Table 1: Spectral Properties of Representative GFP-like Proteins from Diverse Organisms

| Protein Name | Source Organism | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| avGFP (wt) | Aequorea victoria | 395/475 | 509 | ~21,000-30,000 | 0.79 | [25] |

| EGFP | Engineered variant | 488 | 509 | 55,000 | 0.60 | [25] |

| StayGold | Cytaeis uchidae | 496 | 509 | 159,000 | 0.93 | [35] |

| CU17S (V168A) | Cytaeis uchidae | 496 | 509 | 159,000 | 0.93 | [35] |

| mcavRFP | Montastraea cavernosa | 490 (minor), ~550 (major) | 605 (with ~630 shoulder) | Not reported | Not reported | [17] |

| zoan2RFP | Zoanthus sp. | 558 | 583 | Not reported | Not reported | [17] |

| GFPa1 | Branchiostoma floridae | 492 | 505 | Not reported | Not reported | [34] |

| GFPf1 | Branchiostoma floridae | Non-fluorescent | Non-fluorescent | Not reported | Not reported | [34] |

Recent Engineering Advances in GFP Properties

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Modern Engineered GFP Variants

| Protein Name | Photostability (t₁/₂, seconds) | Brightness | Oligomerization State | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| StayGold | >10,000 | High | Dimer (tandem dimer available) | Long-term live-cell imaging, SRM |

| EGFP | ~500 | Medium | Monomer | General purpose |

| mNeonGreen | Not reported | High | Monomer | General purpose, fusions |

| sfGFP | Not reported | Medium | Monomer | Fusions with poorly-folding partners |

| PROSS-eGFP | Not reported | Medium | Monomer | Thermostable variant (96°C) |

Experimental Protocols for GFP Characterization

Cloning and Characterization of Novel GFP-like Proteins

The discovery and characterization of new GFP variants follow established molecular biology workflows that can be adapted to diverse biological sources.

Sample Collection and Preparation: Candidate organisms are typically collected during night dives and initially screened using UV flashlights to identify fluorescent specimens [17]. Tissue samples (100-500 mg) are preserved for RNA extraction. For example, in the characterization of 11 new GFP-like proteins, samples included Montastraeca cavernosa, Condylactis gigantea, and Ricordea florida collected from the Florida Keys Marine Sanctuary [17].

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis: Total RNA is isolated from tissue samples using standard protocols (e.g., guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction) [17]. Total cDNA is then amplified using kits such as the SMART cDNA amplification kit (CLONTECH), which enables full-length cDNA synthesis from nanogram quantities of total RNA.

Cloning GFP Genes: Amplified cDNA is used as a template to amplify 3' fragments of GFP-like protein genes using degenerate primers designed against conserved regions, followed by retrieval of 5' flanks via RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends) [17]. Complete coding regions are amplified using primers containing the initiation and stop codons of the open reading frame, often with additional sequences providing bacterial ribosome-binding sites and frameless stop codons to enable efficient expression.

Heterologous Expression and Screening: PCR products are cloned into plasmid vectors (e.g., pGEM-T) and transformed into E. coli hosts such as JM109 strain [17]. Colonies are grown on selective plates supplemented with IPTG for 16-20 hours at 37°C, then incubated for several days at 4°C to allow chromophore maturation. Fluorescent colonies are identified using fluorescence microscopy and selectively streaked for further analysis.

Spectroscopic Characterization: Bacterial cells are harvested, suspended in PBS, and disrupted by sonication [17]. Cleared lysates are obtained by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 minutes), and fluorescent properties are determined using a spectrofluorometer (e.g., Perkin-Elmer LS-50B). Emission spectra should be corrected for the wavelength-dependent sensitivity of the photomultiplier. For proteins with complex maturation pathways like "timer" RFPs, multiple timepoints may be necessary (e.g., "early" samples after 24h at 37°C and "late" samples after additional days at 4°C).

Computational Analysis of GFP Evolution

Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Protein sequences are aligned using structure-based constraints to ensure proper registration of the β-strands forming the GFP barrel [17]. Poorly aligned N- and C-terminal regions are typically excluded from analysis. DNA alignments are then constructed based on the protein alignment.

Phylogenetic trees can be constructed using software such as tree-puzzle under appropriate models of DNA evolution (e.g., HKY model with γ-distributed site variability) [17]. Maximum likelihood trees can be confirmed using packages like PAML under REV models. The resulting phylogenies enable identification of clades and analysis of color distribution patterns across the evolutionary tree.

Selection Pressure Analysis: The strength and direction of natural selection acting on GFP genes can be quantified by comparing rates of nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitutions across lineages and sites [34]. Ratios of dN/dS < 1 indicate purifying selection, while dN/dS > 1 suggests positive selection. These analyses can reveal whether particular amino acid sites or clades have experienced divergent selective pressures related to color conversion.

Research Reagent Solutions for GFP Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GFP Evolutionary Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning Systems | pGEM-T vector, pET28a(+) | Heterologous expression in bacterial systems | pGEM-T allows direct TA cloning of PCR products; pET28a provides strong inducible expression |

| Expression Hosts | E. coli JM109, BL21 | Protein expression and screening | JM109 suitable for general cloning; BL21 optimized for protein production |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | SMART cDNA amplification kit | Full-length cDNA synthesis from limited RNA | Particularly valuable for rare samples or low-abundance transcripts |

| Spectroscopic Equipment | LS-50B spectrofluorometer | Spectral characterization | Enables collection of excitation/emission spectra with correction for detector sensitivity |

| Chromatography Media | Anion-exchange resins | Protein purification and separation of isoforms | Useful for separating different maturation states or spectral variants |

| Phylogenetic Software | tree-puzzle, PAML | Evolutionary analysis and selection pressure detection | Implements maximum likelihood methods for tree reconstruction and dN/dS calculation |

| Cell Lines | HEK293, U2OS, HeLa | Mammalian expression validation | Tests functionality in eukaryotic cellular environment |

| Machine Learning Tools | EpiNNet, htFuncLib | Prediction of functional multipoint mutants | Addresses epistatic interactions in active site design [36] |

Visualization of Evolutionary and Engineering Workflows

GFP Color Evolution Mechanism

High-Throughput Functional Library Design

The evolutionary history of GFP-like proteins demonstrates how the interplay between mutation pressure and natural selection drives functional diversification at the molecular level. The phylogenetic distribution of these proteins across cnidarians and cephalochordates, combined with their diverse spectral properties, provides a compelling model for studying how genetic variation leads to functional innovation. Experimental methods for characterizing new GFP variants continue to evolve, with recent advances in machine learning approaches like htFuncLib enabling more efficient exploration of sequence-function relationships [36]. These findings not only illuminate fundamental evolutionary processes but also provide researchers with enhanced tools for protein engineering applications in basic research and drug development.

Harnessing Nature's Rainbow: GFP Analogs as Tools in Modern Biomedicine and Drug Discovery

The discovery and subsequent development of fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized cell biology, enabling researchers to visualize protein dynamics within living systems. The phylogenetic distribution of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) analogs provides a critical evolutionary context for these technological advancements. Initially discovered in the jellyfish Aequorea victoria [17] [37], GFP-like proteins have since been identified across diverse organisms including other Cnidarians (corals and anemones), Copepods, and Cephalochordates (amphioxus) [17] [38]. This broad phylogenetic occurrence indicates that fluorescent proteins appeared early in animal evolutionary history and have undergone significant diversification. In cephalochordates alone, the GFP gene family has expanded to include at least 13 functional genes, representing the largest known GFP family [38]. This natural diversity provides a rich toolkit of FP variants with different spectral properties and maturation characteristics that researchers have harnessed for protein tagging. The evolutionary trajectory of these proteins reveals a story of gene duplication, divergence, and functional specialization, processes that biotechnology has mirrored in creating the sophisticated FP variants used in modern live-cell imaging [17] [38].

Protein Tagging Methodologies: From Basic Fusions to Advanced Systems

Fluorescent Protein Fusion Tags

The fundamental approach to protein tagging involves genetically fusing the coding sequence of a fluorescent protein to the gene of interest, resulting in a fusion protein that can be visualized in live cells [39]. This methodology typically involves creating either N-terminal or C-terminal fusions, though internal tagging is also possible [39]. The key advantage of FP tagging is its ability to reveal protein localization and dynamics without the need for exogenous substrates or cofactors, as the chromophore forms autocatalytically [17] [39]. Early implementations faced challenges in plant systems due to a cryptic intron in the original jellyfish GFP sequence that was incorrectly processed, but codon optimization resolved this issue, enabling widespread application across diverse biological systems [39].

Advanced Tagging Systems and Pooled Screening Approaches

Beyond direct FP fusions, several sophisticated protein tagging systems have been developed. SNAP-tag technology enables specific labeling of fusion proteins with a variety of fluorescent substrates, allowing simultaneous dual protein labeling and pulse-chase experiments [40]. Recently, pooled screening approaches have dramatically increased throughput. The vpCell (visual proteomics cell) platform uses multicolour tagging with genome-wide intron-targeting sgRNA libraries to generate cell pools where individual clones express two different endogenously tagged fluorescent proteins [41]. This system leverages computer vision and machine learning to identify clones based on the unique "visual barcodes" created by the combination of localization patterns and expression levels of the tagged proteins, enabling simultaneous monitoring of hundreds of proteins in a single experiment [41].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Protein Tagging Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Features | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Fusions [39] | Genetic fusion of FP to protein of interest | Protein localization, dynamics, trafficking | No need for exogenous substrates; suitable for long-term imaging | Large tag size (~25 kD) may affect protein function |

| SNAP-tag/CLIP-tag [40] | Enzyme-based tagging system using small molecule substrates | Simultaneous dual labeling, pulse-chase experiments, receptor internalization | Small tag size; variety of fluorescent substrates | Requires addition of exogenous substrate |

| Pooled Multicolour Tagging (vpCell) [41] | Endogenous tagging with two different FPs using sgRNA libraries | Large-scale protein dynamics screening, drug discovery | High-throughput; monitors hundreds of proteins simultaneously | Complex computational analysis required |

Quantitative Assessment of Fluorescent Proteins

The selection of appropriate fluorescent proteins requires careful consideration of multiple photophysical properties. Quantitative comparisons of over 40 different FPs have revealed significant variations in brightness, photostability, and pH stability [37]. Brightness, defined as the product of extinction coefficient and fluorescence quantum yield, peaks in the middle of the visible spectrum with yellow and orange FPs such as mVenus and mKO [37]. This pattern follows fundamental fluorophore properties, as blue fluorophores (with higher energy transitions) typically have smaller extinction coefficients, while red FPs suffer from lower quantum yields due to reduced fluorophore rigidity in larger conjugated systems [37].

Photostability represents another critical parameter, with measured bleaching half-times ranging from 2.7 seconds for DsRed2 to 530 seconds for mCardinal under identical imaging conditions [37]. Notably, most FPs exhibit "accelerated photobleaching," where the bleaching rate increases supralinearly with illumination intensity [37]. This property has significant implications for microscopy method selection, as laser scanning confocal microscopy (with its high instantaneous intensity) causes dramatically faster photobleaching compared to widefield microscopy at identical total power [37].

Table 2: Photophysical Properties of Selected Fluorescent Proteins [37]

| Fluorescent Protein | Color Class | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Relative Brightness | Photobleaching Half-time (s) | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCerulean | Cyan | 433 | 475 | 0.35 | 108 (in cells) | Monomer |

| EGFP | Green | 488 | 507 | 1.00 | 239 (in cells) | Monomer |

| mVenus | Yellow | 515 | 528 | 1.56 | 58 (in cells) | Monomer |

| mKO | Orange | 548 | 559 | 1.66 | N/A | Monomer |

| mCherry | Red | 587 | 610 | 0.47 | 348 (in cells) | Monomer |

| mKate2 | Far-Red | 588 | 633 | 0.40 | N/A | Monomer |

| mCardinal | Far-Red | 604 | 659 | 0.30 | 530 | Monomer |

Live-Cell Imaging Techniques and Considerations

Maintaining Physiological Conditions