Biofluorescence in Mammals: From Platypus to Flying Squirrel – Mechanisms, Biomedical Applications, and Research Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of biofluorescence in diverse mammalian species, including the platypus and flying squirrels, for a scientific audience.

Biofluorescence in Mammals: From Platypus to Flying Squirrel – Mechanisms, Biomedical Applications, and Research Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of biofluorescence in diverse mammalian species, including the platypus and flying squirrels, for a scientific audience. It covers the foundational biology and recent discoveries, explores advanced detection methodologies and their direct applications in biomedical research and drug discovery, discusses troubleshooting for common experimental challenges in fluorescence imaging, and offers a comparative analysis of fluorescence characteristics and their functional implications. The content synthesizes current research to highlight the potential of mammalian biofluorescence as a source of novel fluorescent compounds and its utility in developing advanced biosensors and high-throughput screening assays.

The Biology of Glowing Mammals: Discovering Biofluorescence from Monotremes to Marsupials

Biofluorescence, a phenomenon where an organism absorbs light at one wavelength and re-emits it at a longer, visible wavelength, is an emerging frontier in mammalian biology [1]. While documented in marine organisms, amphibians, and birds, its prevalence in mammals was largely overlooked until recent, accidental discoveries revealed this trait in a growing list of nocturnal and crepuscular species [2] [3]. These findings span distantly related mammalian groups across multiple continents, including the monotreme platypus, marsupial opossums, and a variety of placental mammals like flying squirrels and springhares [4] [3]. This whitepaper synthesizes the documented cases, quantitative properties, and investigative methodologies central to this field, providing a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals interested in optical biomarkers and novel biological compounds.

Documented Cases and Quantitative Data

The following sections detail key mammalian species in which biofluorescence has been formally documented. The table below provides a consolidated quantitative overview of the biofluorescent properties.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Biofluorescence in Documented Mammalian Species

| Species | Biofluorescence Color | Spectral Peaks (nm) | Chemical Basis | Activity Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) | Green/Cyan [3] | 500-600 [3] | Not Specified [3] | Nocturnal/Crepuscular [3] |

| Flying Squirrels (Glaucomys spp.) | Pink [2] [5] | Not Specified | Organic compounds in fur [5] | Nocturnal [2] |

| Springhares (Pedetes spp.) | Orange-Red [4] | 500 & 650 [4] | Uroporphyrin-I, -III, Coproporphyrin-I, and other porphyrins [4] | Nocturnal [4] |

| Opossums (Didelphidae) | Pink [2] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Nocturnal [2] |

Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus)

The duck-billed platypus, a monotreme, was discovered in 2020 to exhibit biofluorescence. Its brown pelage absorbs ultraviolet (UV) light between 200 and 400 nanometers and re-emits it as visible green or cyan light in the 500-600 nanometer range [3]. This trait was identified in museum specimens, and like other fluorescent mammals, the platypus is primarily active in low-light conditions, possessing UV-sensitive vision that may allow it to perceive this fluorescence [3].

Flying Squirrels (Glaucomysspp.)

North America's flying squirrels were the first placental mammals in which biofluorescence was documented. Under UV light, their fur glows a vivid, bubble-gum pink [2] [5]. This fluorescence is believed to originate from organic compounds within the fur and is present in both museum specimens and living individuals across all three Glaucomys species, regardless of sex or geographic origin [2] [5]. Their strictly nocturnal habits are a key ecological commonality with other fluorescent mammals [2].

Springhares (Pedetesspp.)

Springhares represent a significant discovery as the first documented case of biofluorescence in an Old World placental mammal [4] [6]. Research on both museum specimens and captive individuals revealed a vivid orange-red biofluorescence, with spectral analysis identifying distinct peaks at 500 nm and 650 nm [4]. Chemical analysis determined that the fluorescence originates from several porphyrin molecules, including Uroporphyrin-I, Uroporphyrin-III, and Coproporphyrin-I, within the cuticle of the hair fiber [4]. Notably, the fluorescence persists in museum specimens over a century old and cannot be removed by washing, indicating it is an intrinsic structural property [4] [6].

Experimental Methodologies for Detecting and Analyzing Biofluorescence

The study of biofluorescence in mammals relies on a suite of well-established laboratory and imaging techniques. The workflow typically progresses from initial observation to detailed chemical characterization.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for the detection and analysis of mammalian biofluorescence, progressing from specimen selection to chemical characterization.

UV Light Screening and Documentation

The initial detection of biofluorescence involves illuminating specimens with UV light sources in a darkened environment.

- UV Light Source: Researchers typically use LED UV flashlights or floodlights emitting at a wavelength of 395 nm to excite the specimens [4] [2].

- Documentation: The fluorescence is documented using digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras. Photographs are taken under both visible light and UV illumination [4]. To isolate the emitted fluorescent light and remove residual UV reflection, a 470 nm longpass filter (e.g., Tiffen Yellow 2 #8) is often used in front of the camera lens [4]. White balance is corrected using a standard reference card [4].

Microscopic and Spectral Analysis

Following initial observation, detailed physical and optical analyses are conducted.

- Light Microscopy: Hair samples are examined under a compound light microscope (e.g., Nikon Eclipse E2300) under both visible and UV light at magnifications such as 4x. This technique helps localize the source of fluorescence to specific structures, such as the cuticle of the hair fiber, and confirms it is not a surface contaminant [4].

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: The spectral properties of the fluorescence are characterized using spectroscopy tools like the Ocean Optics USB2000+. This instrument measures the precise wavelengths of light emitted, identifying distinct peaks, such as the 500 nm and 650 nm peaks found in springhare fur [4].

Chemical Characterization

Identifying the fluorescent molecules requires analytical chemistry techniques.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): This is a central technique for separating and identifying the specific fluorescent compounds present in fur extracts. For example, HPLC was used to confirm the presence of a suite of porphyrins (uroporphyrin-I, uroporphyrin-III, heptacarboxylporphyrin, hexacarboxylporphyrin, and coproporphyrin-I) in springhare hair samples [4].

- Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC): TLC is used as a complementary method to separate fluorescent extracts and analyze their constituent compounds [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table outlines essential materials and reagents used in biofluorescence research, based on the methodologies cited in the literature.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| UV Light Source (395 nm) | Provides the excitation wavelength to induce biofluorescence. | LED UV flashlight used on flying squirrels and springhares [4] [2]. |

| Longpass Filter (470 nm) | Blocks reflected UV light, allowing only the emitted fluorescent light to be captured by the camera. | K&F Concept or Tiffen Yellow #8 filter used in springhare research [4]. |

| Fluorescence Spectrometer | Precisely measures the emission spectrum (wavelengths) of the biofluorescence. | Ocean Optics USB2000+ used to identify spectral peaks in springhare fur [4]. |

| HPLC System | Separates and identifies the specific chemical compounds responsible for fluorescence. | Used to isolate and confirm porphyrin types in springhare hair [4]. |

| Compound Microscope | Enables high-magnification visualization of fluorescence location on individual hair fibers. | Nikon Eclipse E2300 used to analyze springhare hair structure [4]. |

| Museum Specimens | Provides a diverse and historically wide sample set for initial screening and study. | Randolph College's collection and Field Museum specimens were pivotal for discovering fluorescence in multiple species [1] [4] [6]. |

| Apiopaeonoside | Apiopaeonoside, CAS:100291-86-9, MF:C20H28O12, MW:460.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Clobetasone Butyrate | Clobetasone Butyrate, CAS:25122-57-0, MF:C26H32ClFO5, MW:479.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Chemical Pathways and Underlying Biology

The biochemical basis of biofluorescence varies between species, involving different molecules and pathways. In the case of springhares, the fluorescence is porphyrin-based.

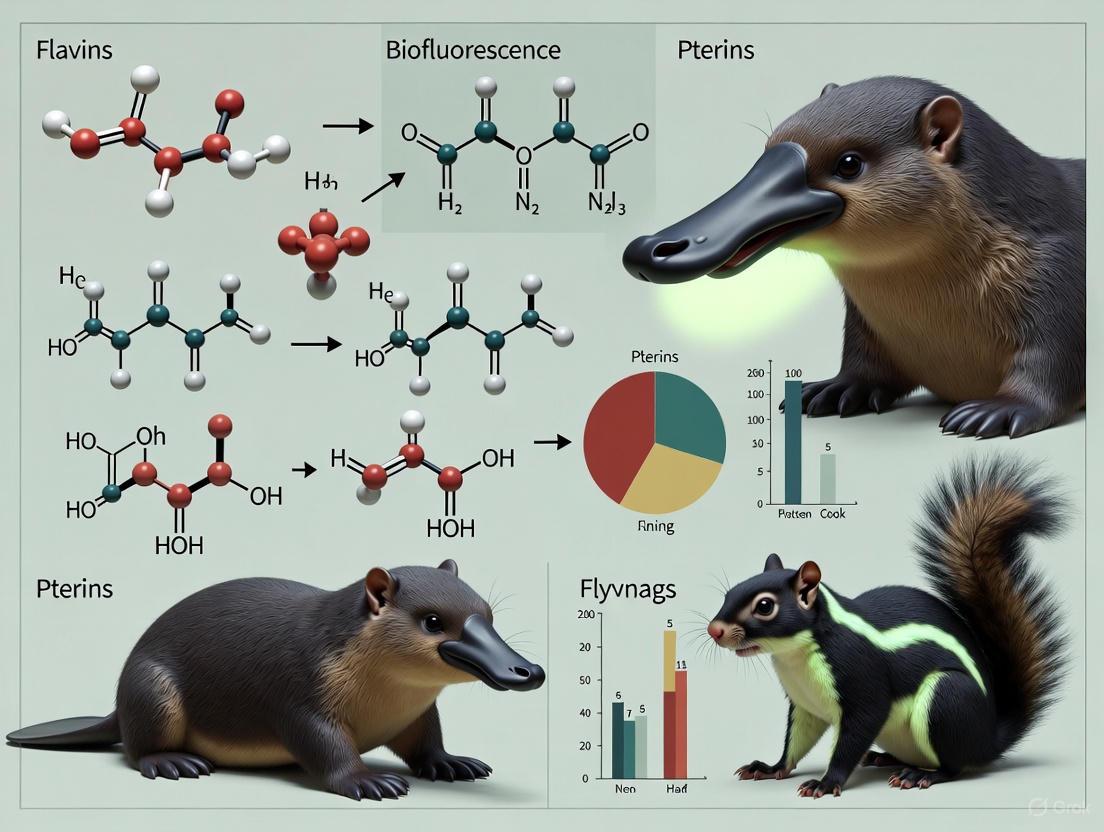

Figure 2: The proposed pathway for porphyrin-based biofluorescence, as identified in springhares. Porphyrins are oxidized byproducts of the heme synthesis pathway that become incorporated into the hair [4].

The discovered porphyrins in springhares, such as uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin, are oxidation products of porphyrinogens, which are intermediates in the biosynthetic pathway for heme [4]. These porphyrin molecules are then incorporated into the growing hair shaft, specifically within the cuticle, where they remain stable for decades [4]. When exposed to UV light, these molecules absorb the high-energy photons and re-emit the energy as lower-energy orange-red light, between 570 and 720 nm, resulting in the observed biofluorescence [4]. The exact genetic and cellular mechanisms that lead to the concentration of these compounds in the fur remain an active area of research.

Biofluorescence, the phenomenon where an organism absorbs light at one wavelength and re-emits it at a different, typically longer, wavelength, represents a growing frontier in mammalian sensory biology [7]. While documented in various marine organisms, reptiles, amphibians, and birds, its confirmed presence in mammals is a relatively recent and expanding field of study [8] [9]. This whitepaper examines the spectral characteristics of biofluorescence in two distantly related mammalian lineages: the monotreme platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) and placental North American flying squirrels (genus Glaucomys). The platypus exhibits a distinctive blue-green fluorescent signature [7] [10], whereas flying squirrels emit a vibrant pink glow [2] [8]. Framed within a broader thesis on the distribution and function of biofluorescence in mammals, this analysis aims to synthesize the quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and potential ecological drivers underlying these phenomena, providing a resource for researchers in zoology, sensory ecology, and bio-inspired material science.

Quantitative Spectral Data Comparison

The documented biofluorescence in the platypus and flying squirrels displays distinct spectral and morphological characteristics. The following table summarizes the core quantitative and qualitative findings from peer-reviewed observations.

Table 1: Comparative Biofluorescence Characteristics in the Platypus and Flying Squirrels

| Characteristic | Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) | Flying Squirrels (Genus Glaucomys) |

|---|---|---|

| Emitted Color | Blue-green, cyan [7] [10] [9] | Brilliant, bubble-gum pink [2] [8] |

| Visible Light Color | Dense brown fur [9] | Varies by species; typically drab for camouflage [2] [11] |

| Location on Body | Dorsal (back) fur: strong fluorescent blue; Ventral (belly) fur: blend of greens and blues [12] | Primarily on the belly and undertail; minor hint on the back [11] |

| Specimens Documented | Multiple museum specimens from Tasmania and New South Wales [7] [9]; confirmed with roadkill specimen [13] | 135+ museum specimens of all three North American species [2] [8] |

| Temporal Range of Specimens | Specimen from 1889 [13] to modern times | Specimens from the 19th to 21st centuries [2] [8] |

| Geographic Range of Findings | Eastern Australia, including Tasmania [9] | Widespread across North America, from Guatemala to Canada [2] [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The discovery and characterization of biofluorescence in these mammals relied on systematic examination of both museum and fresh specimens using controlled ultraviolet light exposure.

Specimen Sourcing and Preparation

- Museum Specimens: Researchers utilized preserved study skins from major natural history collections, including the Field Museum in Chicago and the Science Museum of Minnesota for flying squirrels [2] [8], and the Field Museum and the University of Nebraska State Museum for platypuses [7] [9]. This approach allowed for the examination of a large number of individuals across a wide geographic and temporal range.

- Validation with Fresh Specimens: While the initial findings were on museum specimens, the results were validated using fresh samples. For flying squirrels, the initial discovery was made on a live animal in the wild [2]. For platypuses, observations of road-killed bandicoots and a platypus confirmed that the phenomenon was not an artifact of preservation [13].

UV Illumination and Imaging

- Light Source: Researchers employed ultraviolet (UV) flashlights emitting in the ~365 nm wavelength (UVA spectrum) to illuminate the specimens in darkened rooms [2] [11].

- Control with Visible Light: Standard photographic flashes or room lights were used to capture the baseline appearance of the fur under visible light for direct comparison [2] [8].

- Documentation: The fluorescent response was documented using standard digital cameras. For the platypus, a yellow filter was sometimes used in photography to reveal a more "true" color of the fluorescence [7]. The intensity of fluorescence was quantitatively measured for flying squirrels and compared to non-flying squirrel species [2].

Analysis and Comparison

- Intra-species Consistency: For flying squirrels, researchers analyzed all three North American Glaucomys species and found the pink fluorescence was consistent across sex, age, season, and geography [2] [8].

- Inter-species and Inter-clade Comparison: The studies compared the fluorescent properties of the target species against non-fluorescent relatives (e.g., gray squirrels for flying squirrels) [8] and other known fluorescent mammals (opossums) to establish phylogenetic patterns [10] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key equipment and materials required for conducting research into mammalian biofluorescence.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofluorescence Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Ultraviolet (UV) Flashlight (365 nm) | The primary tool for exciting biofluorescent compounds. A wavelength around 365 nm is standard for this application [11] [13]. |

| Digital Single-Lens Reflex (DSLR) or Mirrorless Camera | For high-resolution documentation of both visible light and UV-induced fluorescence. Allows for manual control of exposure settings. |

| Spectrophotometer | Instrument for precisely measuring the spectral signature (absorption and emission wavelengths) of fluorescent fur samples, moving beyond qualitative color description [13]. |

| Museum Curated Specimen Collections | Provide access to a wide range of species, sexes, and historical specimens for comparative studies across phylogeny and geography [2] [7]. |

| Filter Set (e.g., Yellow Filter) | Used in photography to block reflected UV light and isolate the emitted fluorescent light, providing a more accurate color representation [7]. |

| Dalvastatin | Dalvastatin (CAS 132100-55-1)|HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor |

| Tug-424 | Tug-424, CAS:1082058-99-8, MF:C18H16O2, MW:264.3 g/mol |

Proposed Signaling Pathways and Ecological Functions

The ecological functions of biofluorescence in mammals are not yet definitively known and are an active area of research. The following diagram synthesizes the leading hypotheses and their proposed mechanisms for both the platypus and flying squirrels.

Diagram 1: Proposed Functions of Biofluorescence

Functional Hypotheses for Platypus Biofluorescence

- Camouflage from UV-Sensitive Predators: As a mostly nocturnal and crepuscular forager, the platypus may use biofluorescence to reduce its visibility. By absorbing UV light and re-emitting it as blue-green, it could potentially blend in with the UV-rich, bluish background of twilight or water, making it less detectable to predators like birds of prey or fish that possess UV vision [7] [10].

- Ancestral Trait: Given that biofluorescence has now been documented in all three major mammalian lineages (placental, marsupial, and monotreme), it may be an ancient trait with no current adaptive function, merely retained from a common ancestor [10] [9].

Functional Hypotheses for Flying Squirrel Biofluorescence

- Intraspecific Communication: The brilliant pink glow, most visible on the belly, could serve as a signal between individuals of the same species in low-light conditions. This could help squirrels recognize each other, maintain group cohesion, or facilitate mating, as they are highly social [11].

- Camouflage and Mimicry: The pink fluorescence could be a form of crypsis against UV-fluorescent lichens on trees [2]. A more provocative hypothesis is mimicry: several owl species that prey on flying squirrels also have pink fluorescent undersides. The squirrels' glow may confuse owls into perceiving them as another owl [11].

- Enhanced Visibility in Snow: Snow reflects UV light, which could enhance the visibility of the pink fluorescence, potentially aiding in navigation or communication during winter [2].

The discovery of biofluorescence in the platypus and flying squirrels, with their distinct green-cyan and pink spectral signatures, respectively, challenges the traditional understanding of mammalian visual ecology and communication. These findings suggest that a hidden world of visual cues, imperceptible to human eyes, may play a significant role in the lives of many mammals, particularly those active in low-light conditions [2] [9]. The convergence of this trait in such distantly related species occupying different ecological niches points to either a deeply conserved ancestral mammalian trait or repeated independent evolution driven by the selective pressures of nocturnal life [10] [9].

Future research should prioritize several key areas:

- In Vivo Confirmation: Rigorously document biofluorescence in live, wild individuals across their natural behaviors.

- Spectral Analysis: Precisely measure the emission and excitation spectra of the fur to move beyond qualitative color descriptions [13].

- Biochemical Basis: Identify the specific compounds and structural mechanisms in the fur and hair that produce the fluorescence.

- Behavioral Experiments: Conduct controlled field and lab studies to test the leading functional hypotheses, such as the role in communication and predator avoidance [13].

- Brodened Phylogenetic Surveys: Systematically screen a wider range of mammalian species for biofluorescence to determine its true prevalence and evolutionary history.

Understanding the "why" and "how" of biofluorescence in mammals not only enriches fundamental zoological knowledge but also opens avenues for biomedical and biochemical innovation, such as the development of new fluorescent tags or dyes inspired by natural mechanisms. For drug development professionals, understanding these natural compounds could inform novel imaging techniques. This field stands as a compelling reminder that much remains to be discovered about the perceptual worlds of even our most familiar animal neighbors.

Biofluorescence, the phenomenon where an organism absorbs short-wavelength light and re-emits it as longer-wavelength light, has been documented across an expanding spectrum of mammalian species [4] [14]. This trait, observed in organisms from invertebrates to birds and mammals, involves distinct biochemical mechanisms to produce visible glow. Key discoveries include biofluorescence in New World placental flying squirrels, marsupial opossums, and the monotreme duck-billed platypus [4] [15]. The discovery of vivid biofluorescence in the nocturnal Springhare (Pedetidae) represents a significant expansion of this phenomenon, marking the first well-documented case in an Old World placental mammal and revealing a unique porphyrin-based mechanism [4] [16] [17].

This technical guide explores the biochemical origins of biofluorescence in springhare fur, focusing on the identified porphyrin compounds and their properties. The content is framed within broader research on mammalian biofluorescence, connecting findings from platypus and flying squirrel studies to establish comparative biochemical context. We provide detailed experimental protocols, quantitative data analyses, and visualization of core pathways to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals investigating photoluminescent biological systems.

Biochemical Basis of Mammalian Biofluorescence

Biofluorescence in mammals originates from specific light-absorbing molecules called luminophores present in skin, fur, or bone [18] [19]. These molecules absorb higher-energy (shorter-wavelength) light—typically in the ultraviolet or blue spectrum—and re-emit it as lower-energy (longer-wavelength) visible light [15] [18]. This process is distinct from bioluminescence, where light is generated through internal chemical reactions without initial light absorption [15] [14].

The primary biochemical agents identified in mammalian biofluorescence include:

- Porphyrins: Nitrogen-containing organic compounds that form coordination complexes with metals. These are responsible for pink, red, and orange biofluorescence in species like springhares and bandicoots [4] [18] [19].

- Tryptophan metabolites: Fluorescent compounds derived from amino acid metabolism, documented in mammalian pelage over 50 years ago [18].

- Structural proteins: Keratin and collagen in hair, claws, and bones can exhibit weak fluorescence, though stronger emissions suggest additional specialized compounds [18].

Recent research indicates biochemical diversity in mammalian biofluorescence mechanisms. While protoporphyrin appears ubiquitous across multiple species, different mammals utilize varying combinations of porphyrins and potentially unidentified molecules to produce species-specific fluorescent patterns [18] [19].

Porphyrin-Based Biofluorescence in Springhares

Chemical Profile of Springhare Fur

The vivid biofluorescence observed in both species of springhare (Pedetes capensis and Pedetes surdaster) originates from multiple porphyrin compounds embedded within the hair cuticle [4] [17]. Chemical analyses reveal these porphyrins are not surface contaminants but integral components of the hair structure, remaining present even in museum specimens dating back to 1905 and resisting removal through washing with detergents [4].

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of springhare fur extracts identified a specific profile of porphyrin species [4]:

Table 1: Porphyrin Compounds Identified in Springhare Fur

| Porphyrin Compound | Chemical Characteristics | Fluorescence Properties | Biosynthetic Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uroporphyrin-I | Highly water-soluble porphyrin with eight carboxyl groups | Fluoresces between 570-720 nm [4] | Oxidation of uroporphyrinogen-I, a heme pathway intermediate [4] |

| Uroporphyrin-III | Structural isomer of Uroporphyrin-I | Fluoresces between 570-720 nm [4] | Oxidation of uroporphyrinogen-III [4] |

| Heptacarboxylporphyrin | Porphyrin with seven carboxyl groups | Fluoresces between 570-720 nm [4] | Decarboxylation intermediate of uroporphyrinogen [4] |

| Hexacarboxylporphyrin | Porphyrin with six carboxyl groups | Fluoresces between 570-720 nm [4] | Further decarboxylation from heptacarboxylporphyrin [4] |

| Coproporphyrin-I | Porphyrin with four carboxyl groups | Fluoresces between 570-720 nm [4] | Oxidation of coproporphyrinogen-I [4] |

| Unassigned Molecule | Not matching standard porphyrin mixture, peaks at ~2 minutes in HPLC [4] | Contributes to biofluorescence signature [4] | Unknown, requires further characterization [4] |

Spectrofluorometric analysis of springhare fur sections revealed two distinct peaks of fluorescence emission at 500 nm and 650 nm when excited with UV light [4]. This dual-peak emission pattern contributes to the unique orange-red biofluorescence observed across all examined springhare individuals, though intensity varied between specimens [4].

The porphyrins identified in springhare fur are oxidation products of porphyrinogens, which are intermediates in the biosynthetic pathway of heme [4]. In humans, excess accumulation of these compounds is associated with porphyria, suggesting springhares may have evolved mechanisms to deposit or store excess porphyrins in their fur, potentially avoiding pathological consequences [16].

Anatomical Distribution and Physical Properties

Biofluorescence in springhares exhibits distinctive anatomical patterning. The phenomenon is pronounced on both dorsal and ventral surfaces, with particularly intense fluorescence in the head and posterior regions on the dorsal side and predominant fluorescence along the inner thigh and tail ventrally [4]. The fluorescence displays notable patchiness in both museum specimens and living individuals [4].

Microscopic examination of individual hair fibers reveals that biofluorescence is distributed through the thickness of the cuticle and is absent from the core and tips of hair fibers [4]. This specific localization within the hair structure explains why the fluorescence is not diminished by washing and persists in historical specimens [4].

Comparative analysis indicates biofluorescence appears more vivid in living springhares than in museum specimens, suggesting potential degradation of the fluorescent compounds over time despite the overall stability of the phenomenon [4]. Both male and female specimens fluoresce in the same regions with similar intensity, indicating the trait is not sexually dimorphic [4].

Comparative Biochemistry Across Mammalian Species

Diversity of Fluorescent Molecules in Mammals

Biofluorescence mechanisms vary significantly across mammalian taxa, with different species employing distinct biochemical pathways to achieve photoluminescence:

Table 2: Comparative Biofluorescence in Mammalian Species

| Species | Biofluorescence Color | Identified Compounds | Proposed Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Springhare (Pedetidae) | Orange to red [4] [17] | Multiple porphyrins: uroporphyrin-I, -III, heptacarboxylporphyrin, hexacarboxylporphyrin, coproporphyrin-I [4] | Camouflage from UV-sensitive predators [4] [16]; Porphyrin sequestration [16] |

| Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) | Blue-green [15] | Not fully characterized, different from springhare [15] [18] | Camouflage; Nocturnal recognition [15] |

| Flying Squirrels (Glaucomys spp.) | Pink [1] | Not specified in results | Camouflage against lichens [20] |

| Bandicoots (Perameles spp.) | Pink, yellow, blue, white [18] [19] | Protoporphyrin, uroporphyrin, coproporphyrin, heptacarboxylporphyrin [18] [19] | Possible communication or camouflage [19] |

| North American Bats (6 species) | Green [20] | Not characterized | Unknown; tested for camouflage and conspecific recognition [20] |

The presence of protoporphyrin across all Australian mammals tested in a recent chemical analysis suggests this compound may be a ubiquitous component in mammalian fur, with varying concentrations contributing to interspecific differences in fluorescence patterns [18] [19]. The pink photoluminescence observed in bandicoots, quolls, and possums has been tied to similar porphyrin compounds (uroporphyrin, coproporphyrin, and heptacarboxylporphyrin) as those found in springhares, despite the geographical separation [18] [19].

Evolutionary and Ecological Considerations

The discovery of porphyrin-based biofluorescence in evolutionarily distant mammals—including monotremes (platypus), marsupials (opossums, bandicoots), and placental mammals (flying squirrels, springhares)—suggests several possible evolutionary scenarios [14]. The trait may be an ancient mammalian characteristic that has been retained in specific lineages, or it could represent convergent evolution in nocturnal species facing similar ecological pressures [14].

Most biofluorescent mammals share a nocturnal-crepuscular activity pattern and sensitivity to UV wavelengths, indicating that biofluorescence and UV light perception may be ecologically linked for species active in low-light conditions [4] [14]. Potential functions include:

- Camouflage: Fluorescence may help break up the animal's outline against UV-fluorescent lichens or foliage, making them less visible to UV-sensitive predators [4] [16].

- Intraspecific communication: Fluorescent patterns could facilitate visual recognition between conspecifics in dim conditions [15].

- Porphyrin sequestration: Springhares may deposit excess porphyrins in their fur to avoid pathological accumulation, potentially offering insights for understanding porphyria in humans [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Documenting and Characterizing Biofluorescence

Research into mammalian biofluorescence employs standardized protocols for documentation and chemical characterization:

Visual Documentation Protocol:

- Equipment: Canon EOS 50D or 6D camera with Sigma 17-70mm or Canon 17-40mm lens; 395nm UV LED flashlight; 470nm longpass filter (K&F Concept or Tiffen Yellow #8) [4].

- Photography: Capture images under both visible light (using Canon Speedlite 430EX) and UV illumination [4].

- White Balance Correction: Use standardized white balance cards (DGK Color Tools WB card) for color accuracy [4].

- UV Reflectance Assessment: Utilize specialized UV cameras (Nurugo SmartUV) to measure UV light absorption [4].

Microscopic Analysis:

- Examine hair samples using compound light microscopy (Nikon Eclipse E2300 with DSFI2 camera) under both visible and UV light at 4× magnification [4].

- Compare with control samples (e.g., human hair) to confirm specificity of fluorescence [4].

Chemical Extraction and Analysis Methods

Sample Preparation:

- Collect fur samples from museum specimens, captive individuals, or fresh remains (e.g., roadkill) [4] [18].

- Conduct wash tests using detergents (e.g., Dawn dish soap) to determine if fluorescence is superficial or structural [4].

Chromatographic Separation:

- Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC): Initial separation of fluorescent extracts from hair samples to identify constituent compounds [4].

- High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Advanced separation using Ocean Optics USB2000+ spectrometer for precise compound identification [4].

- Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS): Structural characterization of isolated fluorescent molecules [18].

Chemical Identification:

- Compare retention times and spectral properties against standard porphyrin mixtures [4].

- Identify unknown compounds through mass spectrometry and comparative analysis [4].

Research Reagents and Technical Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Biofluorescence Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Sources | 395 nm UV LED flashlight [4]; UV flood light [4] | Excitation of fluorescent compounds | iLumen8 100 LED UV flashlight [4] |

| Optical Filters | 470 nm longpass filter [4] | Block residual blue light, isolate fluorescence | K&F Concept; Tiffen Yellow #8 [4] |

| Imaging Equipment | DSLR cameras (Canon EOS 50D, 6D) [4]; Nurugo SmartUV camera [4] | Documentation of fluorescence; UV reflectance measurement | Canon systems with Sigma/Nikon lenses [4] |

| Microscopy | Compound light microscope with UV capability [4] | Hair fiber-level fluorescence analysis | Nikon Eclipse E2300 with DSFI2 camera [4] |

| Separation Techniques | Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) plates [4]; High Performance Liquid Chromatography [4] [18] | Separation of complex fluorescent mixtures | Ocean Optics USB2000+ spectrometer [4] |

| Analytical Instruments | Fluorescence spectroscopy [4]; Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry [18] | Quantitative analysis and compound identification | HPLC with spectral analysis [4] [18] |

| Reference Standards | Standard porphyrin mixtures [4] | Compound identification and quantification | Uroporphyrin-I, -III, coproporphyrin-I standards [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Solvent extraction systems; Detergents for wash tests [4] | Compound extraction and contamination testing | Dawn dish soap for control tests [4] |

Biochemical Pathways and Metabolic Origins

The porphyrins identified in springhare fur are intermediates or oxidative products of the heme biosynthetic pathway [4]. Understanding their metabolic origin provides insight into potential physiological implications:

This pathway illustrates how springhares potentially redirect intermediates from heme synthesis to fur deposition. The identified fluorescent porphyrins (uroporphyrin-I, uroporphyrin-III, heptacarboxylporphyrin, hexacarboxylporphyrin, and coproporphyrin-I) represent both enzymatic products and spontaneous oxidation products of pathway intermediates [4].

In humans, accumulation of these compounds is associated with porphyrias, genetic disorders characterized by defects in heme synthesis enzymes [16]. Springhares may have evolved mechanisms to safely sequester excess porphyrins in their fur, thus avoiding potential photosensitivity or neurological symptoms associated with porphyria [16]. This natural detoxification mechanism offers potential insights for therapeutic strategies in human porphyria management.

The biochemical origins of biofluorescence in springhare fur reveal a complex porphyrin-based system distinct from other documented mammalian examples. The specific profile of uroporphyrins, coproporphyrins, and potentially novel fluorescent compounds provides both a unique mechanism for light emission and potential insights into porphyrin metabolism. When framed within broader mammalian biofluorescence research—encompassing platypus, flying squirrels, and recent discoveries in bats and Australian marsupials—the springhare represents a convergent evolutionary solution with distinct biochemical implementation.

Future research directions should include behavioral studies to determine ecological function, comparative genomic analyses to identify evolutionary origins, and further biochemical characterization of the unassigned fluorescent molecules. The potential application of these findings to human porphyria understanding underscores the value of basic biological discovery for advancing biomedical knowledge. As research continues, the expanding catalog of biofluorescent mammals suggests this trait may be more widespread than previously recognized, with springhares representing one particularly vivid example of nature's biochemical diversity.

Biofluorescence, the absorption of light at shorter wavelengths (e.g., ultraviolet) and its re-emission at longer wavelengths (visible light), is increasingly recognized not as a series of isolated curiosities but as a potentially ancient trait that has evolved repeatedly across major mammalian lineages [15] [14] [4]. Research spanning monotremes, marsupials, and placental mammals suggests this phenomenon may have deep evolutionary roots, with significant implications for understanding mammalian sensory ecology and adaptation [14] [21]. This whitepaper synthesizes current findings, details experimental methodologies, and discusses the trait's potential biomedical relevance.

Phylogenetic Distribution and Evolutionary History

The discovery of biofluorescence in distantly related mammalian groups across different continents indicates multiple independent evolutionary origins or an ancient ancestral trait that has been selectively retained [14] [4]. The table below summarizes the phylogenetic distribution of biofluorescence across documented mammalian species.

Table 1: Documented Biofluorescence in Major Mammalian Lineages

| Mammal Group | Example Species | Fluorescence Color | Proposed Compounds | Geographic Region | Activity Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotreme | Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) [15] | Blue-green | Not specified | Australia, Tasmania | Nocturnal/Crepuscular |

| Marsupial | Opossums (Didelphidae) [14] [4] | Not specified | Not specified | Americas (New World) | Nocturnal |

| Marsupial | Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) [14] | Blue (ears, eyes, teeth) | Not specified | Australia | Nocturnal |

| Marsupial | Eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii) [14] | Bright pink | Not specified | Australia | Nocturnal |

| Placental (Rodent) | Flying Squirrels (Glaucomys spp.) [2] [4] | Pink | Not specified | North America | Nocturnal |

| Placental (Rodent) | Springhare (Pedetes spp.) [4] | Orange-red | Porphyrins (e.g., Uroporphyrin-I, Coproporphyrin-I) | Africa (Old World) | Nocturnal |

| Placental | Hedgehog [22] | Pink | Porphyrins | Not specified | Nocturnal |

The presence of biofluorescence in monotremes (egg-laying mammals), marsupials, and placental mammals—groups that diverged from a common ancestor over 150 million years ago—suggests the trait may be evolutionarily ancient [14]. The prevailing hypothesis is that biofluorescence evolved in early mammalian ancestors and was subsequently retained in lineages with nocturnal or crepuscular activity patterns, where ambient UV light is relatively abundant [14] [4]. However, convergent evolution—where the trait emerged independently multiple times in response to similar ecological pressures—remains a strong alternative explanation [21].

Quantitative Data on Biofluorescent Emissions

Quantifying the spectral properties of biofluorescence is critical for comparing the trait across species and investigating its potential functions. The following table consolidates available quantitative data from key studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Spectral Data of Mammalian Biofluorescence

| Species | Emission Peak Wavelengths | Sample Type | Documented Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) | Not specified [15] | Museum specimens (Tasmania, New South Wales) | Consistent blue-green glow across specimens [15] |

| Springhare (Pedetes capensis, P. surdaster) | 500 nm and 650 nm [4] | Museum specimens & captive individuals | Intensity varied; more vivid on head, posterior, inner thigh, and tail; patchy distribution [4] |

| Flying Squirrels (Glaucomys spp.) | Not specified (Pink observed) [2] | Museum specimens & wild observation | Fluorescence was consistent across species, sex, location, and season [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Biofluorescence Research

Standardized methodologies are essential for reproducible discovery and analysis of mammalian biofluorescence. The protocols below are synthesized from recent peer-reviewed studies.

Protocol A: Specimen Imaging and Documentation

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to document biofluorescence in springhares, flying squirrels, and platypuses [15] [2] [4].

1. Equipment Setup:

- Light Sources: A 395 nm LED UV flashlight for illumination [4]. A standard white light source (e.g., Canon Speedlite 430EX) for control images [4].

- Camera: DSLR camera (e.g., Canon EOS 50D or 6D) [4].

- Lens: Macro-capable lens (e.g., Sigma 17–70 mm) [4].

- Filters: 470 nm longpass filter (e.g., K&F Concept or Tiffen Yellow #8) to isolate fluorescent emissions by blocking residual reflected UV/blue light [4].

- White Balance: Use a standard white balance card (e.g., DGK Color Tools WB card) for color correction [4].

2. Imaging Procedure:

- Control Image: Photograph the specimen under normal white light conditions.

- UV Illumination: In a darkened room, illuminate the specimen with the 395 nm UV light source.

- Fluorescence Capture: Photograph the specimen under UV light, both with and without the longpass filter. Maintain consistent camera settings (ISO, aperture, shutter speed) between control and UV images.

- Multiple Angles: Capture dorsal, ventral, and lateral views to document spatial distribution of fluorescence.

3. Data Processing:

- Color Correction: Adjust white balance in the UV-induced images using the reference from the white balance card.

- Comparison: Compare control and UV-induced images to confirm the presence and distribution of biofluorescence.

Protocol B: Chemical Analysis of Fluorescent Compounds

This protocol details the process for identifying the chemical basis of biofluorescence, as applied in the study of springhares [4].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Obtain hair samples from museum specimens or recently deceased individuals.

- To test if fluorescence is superficial, wash a subset of hair samples with a mild detergent (e.g., Dawn dish soap) and re-image under UV light [4].

2. Microscopy:

- Examine individual hair fibers under a compound light microscope (e.g., Nikon Eclipse E2300) under both visible and UV light at 4x magnification [4].

- This helps localize the fluorescence within the hair structure (e.g., to the cuticle rather than the core) [4].

3. Chemical Separation and Identification:

- Extraction: Use solvents to extract fluorescent compounds from hair samples.

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): Separate the crude extract on TLC plates to isolate individual fluorescent compounds [4].

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Further separate and purify compounds using HPLC. Compare the retention times and spectral properties of the isolated compounds to known standards (e.g., a mixture of porphyrins such as uroporphyrin-I, coproporphyrin-I) for identification [4].

Proposed Functions and Ecological Significance

The evolutionary persistence of biofluorescence in diverse mammalian lineages suggests potential adaptive functions, though these are still under investigation.

- Camouflage ("Visual Noise"): One leading hypothesis is that biofluorescence helps camouflage mammals from predators with UV-sensitive vision. By absorbing UV light and re-emitting it as longer wavelengths, the animal's outline could blend into similarly fluorescing backgrounds, such as lichens [14] [2].

- Intraspecific Communication: Fluorescence could serve as a covert visual signal between conspecifics in low-light conditions. Patterns may aid in recognition, mate selection, or social signaling without being easily visible to predators [14] [2].

- Photoprotection or Toxin Sequestration: The presence of porphyrins, as found in springhares, may be linked to metabolic processes. While their fluorescence might be incidental, they could play a role in dissipating excess light energy or sequestering dietary toxins [14] [4].

Critical Analysis and Research Challenges

Interpreting the evolutionary significance of biofluorescence requires careful consideration of several challenges.

- Museum Specimens vs. Live Animals: A critical caveat is that many initial discoveries, including for the platypus, were made on museum specimens. The preservation process can introduce fluorescent chemicals (e.g., in preservatives like borax) or alter native biochemistry, potentially leading to artifacts [22]. Validation in live animals, as done with captive springhares, is essential [4].

- Sensory Unknowns: A function for biofluorescence depends on the visual capabilities of both the emitting animal and its intended (or unintended) receivers. While some nocturnal mammals are known to be sensitive to UV light, the ability of most to perceive the specific fluorescent colors they emit remains unproven [14] [22].

- Phylogenetic Inference vs. Convergent Evolution: Distinguishing between an ancient, conserved trait and multiple independent evolutionary origins is complex. The scattered phylogenetic distribution could support either scenario, and robust statistical models are needed to resolve this question [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and equipment required for conducting research in mammalian biofluorescence.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| UV Light Source (395 nm) | Illuminates specimens to excite fluorescent compounds [4]. | Field observation and laboratory imaging of specimens [2] [4]. |

| Longpass Filter (470 nm) | Blocks reflected UV/blue light, allowing only longer-wavelength fluorescent light to pass to the camera sensor [4]. | Isolating and photographing the true fluorescent signal [4]. |

| DSLR Camera & Macro Lens | High-resolution documentation of fluorescence patterns and colors [4]. | Standardized imaging of specimens under UV and white light [15] [4]. |

| Porphyrin Standards | Chemical references for identifying fluorescent compounds in samples via HPLC [4]. | Identifying uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin in springhare hair [4]. |

| Body-Conforming Animal Mold (BCAM) | Provides a standardized spatial framework for quantitative bioluminescence/fluorescence imaging across animals of different sizes [23]. | Enabling automated, operator-independent analysis of signal distribution in longitudinal studies [23]. |

| Integrating Sphere Spectrometer | Measures the absolute value (total radiant flux or total photon flux) of an optical signal from a sample [24]. | Quantifying the absolute output of a biofluorescent signal for rigorous comparison [24]. |

| Biotin-PEG11-Amine | Biotin-PEG11-Amine | |

| GSHtracer | GSHtracer, MF:C21H21N3O3, MW:363.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization: Evolutionary Relationships and Research Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the phylogenetic context of biofluorescence and the core experimental workflow for its study.

Diagram Title: Biofluorescence Across Mammalian Phylogeny

Diagram Title: Biofluorescence Research Workflow

Implications for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

The study of mammalian biofluorescence extends beyond evolutionary biology, offering tangible prospects for biomedical science.

- Novel Fluorophore Discovery: The diversity of biofluorescent molecules in mammals, such as the unique porphyrin profiles in springhares, represents an untapped resource for discovering new fluorescent proteins or metabolites [4] [21]. These novel molecules could be engineered as biomarkers for fluorescence-guided surgery, where they help delineate tumor margins, or for advanced cellular imaging to track biological processes in real-time [21] [25].

- Standardized Quantitative Imaging: The push for absolute quantification of bioluminescent and fluorescent signals, using tools like integrating sphere spectrometers and body-conforming animal molds (BCAMs), is crucial for preclinical research [23] [24]. This standardization enhances the reproducibility of data in studies modeling human diseases, such as tracking bacterial infections or cancer progression in live animals, thereby accelerating therapeutic development [23].

Biofluorescence is a trait of emerging evolutionary significance, intricately woven into the history of mammalian lineages. While its precise adaptive function requires further validation, its widespread and repeated evolution suggests a potential role in the sensory ecology of nocturnal mammals. For the scientific and drug development communities, this field presents a dual opportunity: to unravel a fascinating aspect of mammalian biology and to mine a new repository of fluorescent tools with the potential to illuminate the path to innovative medical diagnostics and therapies. Future research must prioritize in vivo studies, quantitative imaging, and a deeper investigation into the visual perception of the mammals involved.

Biofluorescence, the phenomenon where an organism absorbs high-energy, short-wavelength light and re-emits it as lower-energy, longer-wavelength light, has been identified as a functionally significant trait across diverse taxonomic groups [26] [27]. Historically studied in marine organisms, amphibians, and birds, its presence in mammals was considered rare until recent discoveries in nocturnal and crepuscular species [2] [8]. This technical guide synthesizes current research on biofluorescence in two distantly related mammalian lineages: the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), a monotreme, and New World flying squirrels (Glaucomys spp.), placental mammals [26] [8]. The independent emergence of this trait in lineages separated by over 150 million years of evolution suggests it may confer critical adaptive advantages in low-light environments [26] [7]. This document examines the potential ecological functions—specifically camouflage, intraspecific signaling, and predator avoidance—within the context of mammalian sensory ecology and evolutionary biology, providing a framework for future investigative work.

Biofluorescence in Mammalian Species: A Comparative Analysis

The discovery of biofluorescence in both platypuses and flying squirrels indicates that this trait is more widespread among mammals than previously recognized. Table 1 provides a comparative summary of biofluorescence characteristics and contexts for these two key groups.

Table 1: Comparative Biofluorescence in Monotreme and Placental Mammals

| Characteristic | Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) | New World Flying Squirrels (Glaucomys spp.) |

|---|---|---|

| Observed Wavelength | Green or cyan, peaking around 500 nm [26] | Brilliant pink [2] [8] |

| Light Condition | Ultraviolet light (385-395 nm) [26] | Ultraviolet light [8] |

| Natural Fur Color | Uniformly brown under visible light [26] | Varies by species; generally drab [2] |

| Activity Pattern | Nocturnal/Crepuscular [26] | Nocturnal/Crepuscular [2] [8] |

| Ecological Niche | Semi-aquatic [26] | Arboreal, gliding [2] |

| Primary Sensory Modes | Electroreception, Mechanoreception [26] | Vision (likely UV-sensitive) [2] |

| Sample Source | Museum specimens [26] | Museum specimens and live wild sightings [2] [28] |

The taxonomic distribution of biofluorescence across all three major mammalian lineages—monotremes, marsupials, and placentals—raises a fundamental question about its evolutionary history. One prevailing hypothesis is that biofluorescence may be an ancestral trait that was present in early mammals [26] [27]. These early mammals are believed to have been predominantly nocturnal, and fluorescence could have provided a selective advantage in their dimly lit environments [27]. The retention of this trait in disparate, distantly-related lineages like monotremes and flying squirrels, but not necessarily in their diurnal relatives, supports the idea that it is an ancient adaptation that persists only where it remains ecologically relevant [26] [7].

Potential Ecological Functions

The ecological drivers of biofluorescence are not yet fully understood, but several compelling hypotheses have emerged from recent research, centered on camouflage, intraspecific signaling, and predator avoidance.

Camouflage

The camouflage hypothesis proposes that biofluorescence helps to conceal the animal from detection by other species.

- Background Matching: For flying squirrels, their pink fluorescence may serve as crypsis by matching the fluorescence of certain lichens found on the trees in their arboreal habitat [2] [8]. This would break up the animal's outline against a fluorescing background in UV-rich twilight conditions.

- UV Absorption for Concealment: For the platypus, the mechanism may be different. Its fur absorbs UV light and re-emits it as blue-green wavelengths [26] [10]. In an environment rich in UV light, this transformation could potentially reduce the contrast between the platypus and its background from the perspective of a UV-sensitive predator. By absorbing the UV light that would otherwise be reflected, the platypus may appear less conspicuous against its surroundings [26] [29].

Intraspecific Signaling

Biofluorescence may play a role in communication between individuals of the same species, particularly during crepuscular or nocturnal activity when visual cues are limited.

- Conspecific Recognition: The glowing patterns could facilitate individuals in locating or recognizing one another in low-light conditions [10] [11]. Flying squirrels are known to be highly social, and their fluorescence could aid in maintaining group cohesion or signaling presence at shared feeding sites [11].

- Non-Sexual Signaling: In both platypuses and flying squirrels, the fluorescence appears to be non-sexually dimorphic; it is present in both males and females with similar patterns and intensity [26] [8]. This suggests the trait is not primarily used for mate selection but could instead function for general intraspecific communication [26].

Predator Avoidance

This hypothesis suggests biofluorescence functions to deter or confuse predators.

- Predator Mimicry (Batesian Mimicry): A prominent theory for flying squirrels is that they mimic the biofluorescence of owls [11] [28]. Several owl species that prey on flying squirrels also have pink fluorescent undersides [11]. A squirrel displaying a similar glow mid-glide might momentarily confuse an owl predator into perceiving it as another, potentially dangerous, owl, thereby increasing the squirrel's chance of survival [28].

- Unprofitable Prey Illusion: Alternatively, the vibrant, unexpected glow could serve as an aposematic signal or startle a predator, making the prey appear unpalatable or novel, thus interrupting an attack [7]. However, this function is considered less likely for the platypus, which relies more on electroreception than vision and may not use the trait for conspicuous signaling [26].

Table 2: Assessment of Ecological Function Hypotheses

| Proposed Function | Plausibility for Platypus | Plausibility for Flying Squirrels | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camouflage | High [26] [10] | High [2] [8] | UV absorption; lichen fluorescence matching. |

| Intraspecific Signaling | Low [26] | High [11] | Non-dimorphic glow; highly social behavior. |

| Predator Avoidance | Moderate [26] [29] | High (via mimicry) [11] [28] | Shared fluorescence with predatory owls. |

Experimental Methodologies for Biofluorescence Research

The study of biofluorescence in mammals relies on specialized equipment and rigorous protocols to accurately document and analyze the phenomenon.

Specimen-Based Detection and Workflow

Initial discoveries and subsequent verification often begin with museum specimens, allowing for controlled examination. The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for specimen-based detection.

The process involves multiple, parallel methods of data collection to ensure robust findings [26]:

- Visible and UV Light Photography: The process begins by documenting the specimen's appearance under normal visible light as a baseline. It is then illuminated in a darkroom with a UV light source (e.g., 385-395 nm). Photographs are taken under this UV light both with and without a longpass filter (e.g., 470 nm) to block reflected UV and blue light, making the fluorescent glow more visible [26].

- UV Reflectance Imaging: This technique uses specialized UV cameras to measure how much UV light is reflected (not absorbed) by the pelage. Areas of low reflectance indicate high UV absorption, which is a prerequisite for biofluorescence [26].

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: This quantitative method is used to precisely measure the fluorescent properties of the fur. A spectrometer with a deuterium light source is used to take emission spectra from multiple points on the specimen. This data reveals the peak wavelength of the emitted fluorescent light (e.g., ~500 nm for platypus, indicating a green-blue glow) and confirms the absorption of UV wavelengths [26].

Field Validation

While museum-based research is foundational, field validation with live animals is critical to confirm that the phenomenon exists and functions in a natural context. This involves using portable UV flashlights to observe and document wild individuals, as was done anecdotally with flying squirrels [2] [11]. For the platypus, field-based research is identified as an essential next step to understand the trait's ecological function in the wild [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment for Biofluorescence Research

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| UV Light Source | To provide the ultraviolet excitation light required to induce fluorescence. | A 385-395 nm LED UV flashlight used to illuminate specimens in a darkroom [26] [11]. |

| Full-Spectrum Camera | To capture images in both the visible and ultraviolet spectra. | A modified Canon EOS 50D used to photograph platypus specimens under UV light [26]. |

| Longpass Filter | A filter that blocks short wavelengths (UV, blue) and allows longer wavelengths to pass, isolating the fluorescent signal. | A 470 nm longpass filter used to prevent reflected UV light from obscuring the fluoresced green/cyan light [26]. |

| Fluorescence Spectrometer | To quantitatively measure the intensity and peak wavelength of the emitted fluorescent light. | An Ocean Optics Flame-S spectrometer used to create fluorescence spectra of platypus fur, showing a peak at 500 nm [26]. |

| Museum Specimens | Preserved specimens that provide a readily available and comparative resource for initial discovery and study. | Examination of flying squirrel skins at the Field Museum and platypus specimens from multiple museums to confirm the trait across geography and time [26] [8]. |

| MrgprX2 antagonist-8 | MrgprX2 antagonist-8, MF:C24H24ClF3N4O3S, MW:541.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ethyllucidone | Ethyllucidone, MF:C17H16O4, MW:284.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The discovery of biofluorescence in platypuses and flying squirrels has unveiled a new dimension of mammalian sensory ecology. The evidence suggests that this trait likely serves an adaptive function, with camouflage and predator avoidance appearing as the most compelling hypotheses for its persistence in these nocturnal and crepuscular species. The phylogenetic distance between these mammals further implies that biofluorescence might be an ancient, though sparsely retained, trait among mammals.

Despite these significant findings, the field is still in its infancy. Critical knowledge gaps remain. Future research must prioritize field studies to observe these phenomena in wild populations, confirming the laboratory and museum-based findings and allowing for direct testing of ecological function [26]. Furthermore, behavioral and visual ecology studies are essential to determine if these mammals can perceive the UV and fluorescent signals they produce, which is a fundamental requirement for any intraspecific communication function [2] [28]. Finally, a broader comparative approach—systematically screening a wider array of mammalian species, particularly those with low-light activity patterns—will help establish the true prevalence of biofluorescence and clarify its evolutionary history [27]. Unraveling the mystery of glowing fur will undoubtedly provide deeper insights into the hidden lives of mammals and the selective pressures that have shaped their evolution.

From Field Discovery to Lab Application: Detection Techniques and Biosensor Development

The discovery of biofluorescence in diverse mammalian species, including the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) and flying squirrels, has revealed a hidden dimension of mammalian visual ecology [26] [27]. This phenomenon, where organisms absorb short-wavelength light (such as ultraviolet radiation) and re-emit it as longer-wavelength visible light, provides a potential adaptive advantage in low-light conditions and enables new forms of cryptic signaling [26]. Documenting this phenomenon requires specialized imaging methodologies that can be applied across both field and museum settings. This technical guide provides researchers with comprehensive protocols for ultraviolet-induced visible luminescence imaging, standardized for consistent documentation of biofluorescence in mammalian specimens.

Biofluorescence in Mammalian Research Context

Biofluorescence has been documented across all major mammalian lineages, including monotremes (platypus), marsupials (opossums), and placental mammals (flying squirrels) [26] [27]. The platypus, a semi-aquatic monotreme, exhibits pelage that appears uniformly brown under visible light but fluoresces green or cyan under UV light, with spectral peaks around 500 nm [26]. Similarly, certain flying squirrel species display pink fluorescence under UV illumination [27]. These discoveries share common ecological contexts: most biofluorescent mammals identified to date are nocturnal or crepuscular, suggesting the trait may be adaptive in low-light environments [26] [27].

The functional significance of mammalian biofluorescence remains an active research area. Current hypotheses suggest potential roles in intra-specific communication, camouflage against UV-sensitive predators, or enhanced visual acuity in dim environments [26] [27]. For the platypus, which primarily navigates via mechanoreception and electroreception, biofluorescence may function more for reduced visibility to predators than for conspecific signaling [26]. Testing these hypotheses requires robust, standardized imaging methodologies applicable across diverse research settings.

Fundamentals of UV-Induced Visible Luminescence Imaging

Ultraviolet imaging encompasses two distinct techniques: reflected ultraviolet (RUV) imaging, which captures UV radiation reflected from surfaces, and ultraviolet-induced visible luminescence (UVL) imaging, which records the visible light emitted by materials when excited by UV radiation [30]. Biofluorescence documentation primarily utilizes UVL imaging.

In UVL imaging, ultraviolet radiation (typically in the UV-A spectrum ranging from 315-400 nm) excites certain molecules within a specimen, causing them to emit longer-wavelength visible light through photoluminescence [30]. The critical technical requirement is ensuring that only the emitted visible light is recorded by the camera, while all reflected UV radiation is blocked [31] [32]. This requires precise combinations of radiation sources and camera filtration.

Table 1: Ultraviolet Spectrum Bands Relevant to Biological Imaging

| Band | Wavelength Range | Transmission through Glass Lenses | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-A (Longwave) | 315-400 nm | Yes | Most common band for UVL imaging of biological specimens |

| UV-B (Middlewave) | 280-315 nm | No (requires quartz lenses) | Specialized applications |

| UV-C (Shortwave) | 200-280 nm | No (requires quartz lenses) | Limited use, potentially damaging to tissues |

Equipment and Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting appropriate UV radiation sources is fundamental to successful fluorescence imaging. Sources should provide even illumination with peak emissions between 360-370 nm for optimal results with biological specimens [32].

- Low-pressure mercury lamps ("black lights"): These sources emit longwave UV with a peak around 365 nm and are widely used in museum settings [32] [30]. They provide stable, even illumination suitable for documenting larger specimens.

- LED-based UV sources: Modern LED systems offer customizable wavelength outputs, portability, and minimal heat generation, making them ideal for field applications [32]. Their specific peak emissions should be verified against manufacturer specifications.

- Xenon arc lamps: High-intensity sources such as Hamamatsu LC8 with 200W xenon lamps provide broad-spectrum output that can be filtered to specific UV ranges [31]. These are particularly valuable for spectroscopic analysis of fluorescence properties.

All UV sources should be tested for visible light leakage, which can compromise fluorescence imaging by overwhelming the weaker emitted signals [32]. Additional filtration (such as Baader U-Venus filters) may be necessary to purify the excitation light [31].

Camera Systems and Filtration

Digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras are commonly used for UVL imaging, with full-spectrum modifications recommended to enhance UV sensitivity [31] [33]. The most critical component for UVL imaging is the filter placed over the camera lens, which must block all reflected UV and transmitted visible blue light while allowing the fluoresced wavelengths to pass [31] [32].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for UV Fluorescence Imaging

| Equipment Category | Specific Products/Models | Technical Specifications | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV Radiation Sources | Low-pressure mercury lamps (e.g., SuperBright II model 3368) | Peak emission ~365 nm | Providing UV-A excitation radiation |

| LED UV flashlights | 385-395 nm output | Portable field applications | |

| Hamamatsu LC8 with Xenon lamp | 200W with filtration capability | High-intensity laboratory imaging | |

| Camera Filters | Schott KV-418 (discontinued) | Low fluorescence under UV | Reference standard for UV blocking |

| Kodak Wratten 2E | Blocks UV, transmits some blue | Filtering reflected UV radiation | |

| Peca 918 | IR blocking | Preventing infrared contamination | |

| Longpass filters (e.g., 470 nm) | Blocks wavelengths below cutoff | Isolating fluoresced visible light | |

| Camera Systems | Modified DSLR (full-spectrum) | IR-cut filter removed | Enhanced UV/IR sensitivity |

| Canon EOS models (50D, 6D, 5D Mark II/III) | Standard internal filtration | Documenting fluorescence | |

| Reference Standards | UV-Gray card | Calibrated for ~368nm excitation | White balance standardization |

| Spectralon reflectance standards | 95% and 10% reflectance | Quantitative intensity calibration |

Standardization and Calibration Tools

Consistent, reproducible documentation requires standardized reference materials. The UV-Gray card and Target-UV products provide calibrated references that appear neutral under specific UV excitation (approximately 368 nm), enabling consistent white balance and exposure across different imaging sessions [32]. Including standardized reflectance standards (e.g., 95% and 10% reflectance panels) within images facilitates quantitative comparison of fluorescence intensity across specimens and research sessions [34].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Museum-Based Specimen Imaging

The following protocol summarizes methodologies successfully employed in documenting platypus biofluorescence [26], adaptable for various mammalian specimens.

Museum Imaging Workflow

Specimen Preparation: Clean specimens to remove dust or contaminants that may fluoresce. Position specimens with standardized reflectance targets (95% and 10% reflectance) within the frame [26] [34]. For dorsal and ventral documentation, reposition specimens systematically.

Environmental Configuration: Conduct imaging in completely dark environments to eliminate ambient light contamination [26]. Position UV radiation sources approximately 40 cm from specimens at 45° angles to minimize specular reflection [26] [31].

Visible Light Documentation: Capture reference images under standard visible illumination using DSLR cameras with conventional lenses and lighting (e.g., Canon Speedlite 430EX) [26]. These provide baseline appearance for comparison.

UV-Induced Luminescence Imaging:

- Camera Configuration: Use full-spectrum modified DSLR cameras with UV-transmissive lenses (e.g., Rayfact 105mm f4.5) [26] [31].

- Filtration: Employ longpass filters (470nm cutoff) that block reflected UV and blue light while transmitting fluoresced longer wavelengths [26].

- Exposure Settings: Use apertures of f/11 and ISO 6400 as starting points, adjusting exposure time to achieve optimal signal without saturation [31]. Record images in RAW format for maximum post-processing flexibility [32].

Spectroscopic Validation: For quantitative analysis, use fluorescence spectroscopy (e.g., Ocean Optics Flame-S-UV-VIS-ES spectrometer) to measure emission spectra at multiple points on specimens [26]. Compare against polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) diffuse reflectance standards.

Image Processing: Process RAW files using reference standards for white balance and exposure normalization. Maintain consistent processing parameters across specimen groups for comparative analysis.

Field Imaging Protocols

Field documentation of biofluorescence in living mammals presents unique challenges, including environmental variables and animal welfare considerations.

Equipment Preparation: Utilize portable UV sources (LED flashlights emitting 385-395 nm) and weather-sealed camera systems [26]. Include compact reference standards for field calibration.

Animal Ethics and Safety: Ensure UV exposure complies with animal welfare guidelines. Limit exposure duration and intensity to minimize potential stress or retinal damage to subject animals.

Documentation Sequence:

- Capture visible light references under natural conditions.

- Implement darkness adaptation (using moonless nights or temporary shading).

- Apply brief UV illumination from oblique angles to document fluorescence.

- Include reference standards in initial field images for subsequent normalization.

Data Recording: Document environmental conditions (ambient light, temperature, humidity) and individual animal metadata (species, sex, age class) for contextual analysis.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Qualitative Assessment

Initial fluorescence assessment involves documenting spatial patterns and coloration. The platypus exhibits green-to-cyan fluorescence uniformly distributed across dorsal and ventral pelage [26]. Flying squirrels show distinctive pink fluorescence [27]. Document pattern consistency across individuals and between sexes to assess potential sexual dimorphism.

Quantitative Analysis

For quantitative comparisons, extract fluorescence intensity values using image analysis software. Normalize measurements against reference standards included in images. Spectral characterization provides precise emission profiles; platypus pelage demonstrates fluorescence peaks around 500 nm [26].

Table 3: Quantitative Fluorescence Parameters in Documented Mammals

| Species | Visible Light Appearance | UV-Induced Fluorescence | Spectral Peak | Documentation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) | Uniform brown | Green/cyan | ~500 nm | Museum specimens [26] |

| Flying Squirrels (Various species) | Species-typical pelage | Pink | Not specified | Field observation and museum [27] |

| Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) | Grayish fur | Various: red, orange, yellow, blue, purple | Not specified | Museum and live animals [26] |

Methodological Validation

When interpreting results, several validation considerations ensure accurate conclusions. Filter fluorescence should be assessed independently; some photographic filters themselves fluoresce under UV exposure, potentially creating color casts [31]. Test filters by exposing them to UV radiation while observing through validated non-fluorescent filters.

Ensure observed fluorescence originates from specimens rather than optical systems. Lens elements may fluoresce; proper filtration before light enters the lens prevents this artifact [31]. Systematically document and account for potential autofluorescence from preservatives or contaminants on museum specimens.

Applications in Mammalian Biofluorescence Research

The methodologies outlined enable critical research applications for understanding mammalian biofluorescence. Standardized imaging facilitates comparative analysis across taxa, environments, and preservation conditions. For platypus research, these techniques confirmed the first documented case of biofluorescence in monotreme mammals [26]. In flying squirrels, imaging connected observations in museum specimens with field documentation [27].

Long-term temporal studies using consistent methodologies can track potential changes in fluorescence properties throughout life history stages or across seasons. Experimental approaches can manipulate light environments to test ecological hypotheses regarding the adaptive significance of biofluorescence.

Technical standardization enables collaborative research across institutions, essential for studying rare or geographically restricted species. As these methodologies become more widely adopted, they will illuminate the extent and functional significance of biofluorescence across the mammalian radiation.

UV-induced visible luminescence imaging provides a powerful, non-destructive methodology for documenting and analyzing biofluorescence in mammalian species across field and museum contexts. The technical protocols outlined—encompassing specialized equipment, standardized imaging parameters, and rigorous validation procedures—enable reproducible documentation of this fascinating biological phenomenon. As research continues to reveal biofluorescence across diverse mammalian taxa, these standardized methodologies will be essential for comparative analyses and ecological interpretation of this hidden visual dimension of mammalian biology.

Fluorescence is a photophysical process in which a molecule, known as a fluorophore, absorbs high-energy light and subsequently emits lower-energy light. This process is distinct from bioluminescence, where light is generated by a chemical reaction. In fluorescence, the absorption of a photon of energy hνEX promotes the fluorophore to an excited electronic singlet state. Following a finite excited-state lifetime (typically 1–10 nanoseconds), during which the fluorophore undergoes conformational changes and interacts with its molecular environment, a photon of lower energy hνEM is emitted, returning the fluorophore to its ground state [35]. The difference in energy or wavelength between the excitation and emission photons is known as the Stokes shift, a fundamental property that allows emission photons to be detected against a low background, isolated from excitation photons [35] [36].

Biofluorescence, the occurrence of this phenomenon in living organisms, has been well-documented in marine life such as jellyfish and corals, and in various insects. However, its discovery in mammals is a relatively new and rapidly expanding field of research. The initial discovery of pink biofluorescence in flying squirrels in 2018 ignited widespread interest, leading scientists to investigate other mammalian species [1]. Subsequent research has confirmed biofluorescence in a range of mammals, including the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), opossums, spring hares, and wombats [15]. In the platypus, studies of preserved specimens have revealed that their fur emits a blue-green fluorescent glow when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light [15]. This glow results from the fur absorbing higher-energy, shorter-wavelength UV light and emitting it as lower-energy, longer-wavelength visible light, a process characteristic of biofluorescence [15] [1]. The study of biofluorescence in mammals, including ongoing work with museum specimens such as a 120-year-old platypus, is enhancing our understanding of the distribution and potential functions of this trait in mammalian biology [1].

Fundamentals of Fluorescence Emission

The Fluorescence Process and Spectra

The fluorescence emission process can be precisely delineated using a Jablonski diagram, which illustrates the electronic state transitions of a fluorophore. The process is cyclical and comprises three key stages, provided the fluorophore is not irreversibly destroyed (a phenomenon known as photobleaching) [35]:

- Excitation: A photon of energy (hνEX) from an external source (e.g., a laser) is absorbed by the fluorophore, creating an excited electronic singlet state (S1') [35].

- Excited-State Lifetime: The excited state exists for a finite time (typically 1–10 nanoseconds). During this period, the fluorophore undergoes conformational changes and interacts with its molecular environment, leading to a relaxed singlet excited state (S1`) from which fluorescence emission originates. Some molecules may return to the ground state via non-fluorescent pathways such as collisional quenching or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [35].

- Fluorescence Emission: A photon of energy (hνEM) is emitted, returning the fluorophore to its ground state (S0). Due to energy dissipation during the excited-state lifetime, the emission photon has lower energy and a longer wavelength than the excitation photon, resulting in the Stokes shift [35] [36].