Excitation Wavelength Optimization for Fluorescent Proteins: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing excitation wavelengths for fluorescent proteins (FPs).

Excitation Wavelength Optimization for Fluorescent Proteins: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing excitation wavelengths for fluorescent proteins (FPs). It covers the foundational principles of FP spectral properties and chromophore dynamics, explores methodological applications in biosensors and live-cell imaging, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and validates approaches through comparative analysis and standards. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource aims to enhance experimental design, improve data quality, and advance the application of fluorescent proteins in biomedical sciences.

Understanding Fluorescent Protein Spectra: From Chromophore Chemistry to Spectral Diversity

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized biomedical research by enabling scientists to visualize gene expression, track cellular dynamics, and study protein localization in living systems [1]. The journey began with the isolation of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) from the Aequorea victoria jellyfish in the 1960s [2] [1]. Since the groundbreaking development of a genetically encodable GFP marker in 1994, protein engineering has created a vast palette of FPs spanning the entire visible spectrum, from blue to far-red [2] [3]. This expansion allows researchers to perform multi-color imaging experiments, tracking multiple cellular components simultaneously. The core structure of most FPs is an 11-stranded β-barrel that protects a central chromophore formed from three amino acids [2] [1]. The selection of the appropriate FP is critical and depends on the experimental setup, as factors such as brightness, photostability, and the specific excitation lasers available on a microscope or flow cytometer directly impact data quality [4] [3].

The Fluorescent Protein Spectrum: A Quantitative Guide

Selecting the right fluorescent protein requires matching its spectral properties to your instrumentation and experimental goals. The following tables summarize the key characteristics of commonly used FPs across the color spectrum.

Table 1: Green, Blue, and Cyan Fluorescent Proteins

| Protein Name (Acronym) | Excitation Maximum (nm) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Molar Extinction Coefficient | Quantum Yield | Relative Brightness (% of EGFP) | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superfolder GFP (sfGFP) | 485 | 510 | 83,300 | 0.65 | 160 | Monomer |

| Enhanced GFP (EGFP) | 484 | 507 | 56,000 | 0.60 | 100 | Monomer |

| Emerald | 487 | 509 | 57,500 | 0.68 | 116 | Monomer |

| mWasabi | 493 | 509 | 70,000 | 0.80 | 167 | Monomer |

| Azami Green | 492 | 505 | 55,000 | 0.74 | 121 | Monomer |

| TagGFP | 482 | 505 | 58,200 | 0.59 | 110 | Monomer |

| mTagBFP | 399 | 456 | 52,000 | 0.63 | 98 | Monomer |

| EBFP2 | 383 | 448 | 32,000 | 0.56 | 53 | Monomer |

| Cerulean | 433 | 475 | 43,000 | 0.62 | 79 | Monomer |

| mTurquoise | 434 | 474 | 30,000 | 0.84 | 74 | Monomer |

Table 2: Yellow, Orange, Red, and Far-Red Fluorescent Proteins

| Protein Name (Acronym) | Excitation Maximum (nm) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Key Properties & Applications | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mNeonGreen | ~506 | ~517 | Very bright; often used as a GFP alternative [4]. | Monomer |

| mYPet | ~517 | ~530 | Bright yellow FP; used in vivo [4]. | Monomer |

| PSmOrange3 | 550 / 614 | 564 / 655 | Orange-to-far-red photoconvertible; ideal for PALM and protein tracking [5]. | Monomer |

| TagRFP-T | ~555 | ~584 | Red FP suitable for flow cytometry and imaging [4]. | Monomer |

| mRuby2 | ~559 | ~600 | Red FP; brightness and photostability assessed in vivo [4]. | Monomer |

| mCherry | ~587 | ~610 | One of the most widely used red FPs; part of the "fruit" palette [4] [3]. | Monomer |

| mKate2 | ~588 | ~633 | Far-red FP; emits at longer wavelengths [4]. | Monomer |

| E2-Crimson | ~611 | ~646 | Long-red FP; emission >640 nm for low autofluorescence [3]. | Not Specified |

| TagRFP657 | ~611 | ~657 | Long-red FP; emission >650 nm [3]. | Not Specified |

| mNeptune | ~600 | ~650 | Far-red FP; engineered for bright emission in the far-red [2] [3]. | Monomer |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My fluorescent protein signal is dim or not detectable. What could be the cause? A dim signal can stem from several issues. First, the FP may not be folding or maturing correctly at 37°C; ensure you are using a variant optimized for mammalian systems, such as those with the F64L mutation [1]. Second, your excitation light may not match the FP's peak absorbance. Always consult the excitation maximum and use the appropriate laser line or filter set [3] [6]. Third, for intracellular targets, confirm that your antibody or FP fusion is accessible; an antibody binding an intracellular epitope will require permeabilization for immunostaining [6].

Q2: What is photobleaching and how can I prevent it? Photobleaching (or fading) is the permanent loss of fluorescence upon illumination, caused by photon-induced chemical damage to the fluorophore [7] [8]. To minimize it:

- Reduce Light Dose: Use lower light intensity (e.g., with neutral-density filters) and shorter exposure times during acquisition [7].

- Use Antifade Reagents: Include commercial antifade mounting media in your sample preparation. These reagents prevent reactions that destroy excited fluorophores, thereby extending their fluorescent lifetime [7] [8].

- Choose Stable Fluorophores: Newer synthetic dyes (e.g., AlexaFluor dyes) and engineered FPs like mRuby2 or PSmOrange3 often have superior photostability compared to older variants like FITC [7] [5].

Q3: For live-cell imaging, should I choose GFP or a red-shifted fluorescent protein? Red and far-red FPs (emission >600 nm) are often preferable for live-cell and deep-tissue imaging. Light in this spectral region suffers from less scattering in biological tissues and is associated with lower autofluorescence and phototoxicity compared to blue or green light [2]. Furthermore, the spectral region between 600-900 nm is considered ideal for whole-cell imaging because the absorption by water and hemoglobin is minimal [2].

Q4: I see high background in my images. How can I reduce it? High background, or autofluorescence, is common in tissue sections and some primary cells. It is most prominent in the blue-green wavelength range [4] [6]. To combat this:

- Use a Far-Red FP: Switch to a red or far-red FP (e.g., mCherry, mKate2), as autofluorescence is significantly lower at these longer wavelengths [4] [3].

- Include Controls: Always run an unstained control to determine the level of autofluorescence in your sample [6].

- Use Autofluorescence Quenchers: Commercial reagents are available to quench lipofuscin-based tissue autofluorescence [6].

- Check Antibody Specificity: Perform staining controls with secondary antibody alone to rule out non-specific binding [6].

Key Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Assessing FP Brightness and Photostability In Vivo

This protocol, adapted from a comparative study in C. elegans, provides a methodology for quantitatively comparing FPs in a live animal model system [4].

- Strain Generation: Use CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to generate transgenic strains expressing the FPs of interest (e.g., GFP, mNeonGreen, mCherry, mRuby2) as fusions to the same protein, inserted into the identical genomic locus. This ensures expression levels are comparable.

- Sample Preparation: Collect and stage synchronized embryos from each transgenic strain.

- Image Acquisition: Mount embryos side-by-side on the same slide. Image using a spinning-disk confocal microscope with standardized settings (e.g., laser power, exposure time, EM-CCD gain) for direct comparison.

- Quantitative Analysis:

- Brightness: Measure the mean fluorescence intensity within a defined region of interest (e.g., the plasma membrane) for each FP.

- Photostability: Subject a defined area to continuous illumination and plot the fluorescence intensity over time to calculate the photobleaching half-time.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the quantified brightness and photostability metrics across the different FPs to identify the optimal tag for your experimental conditions.

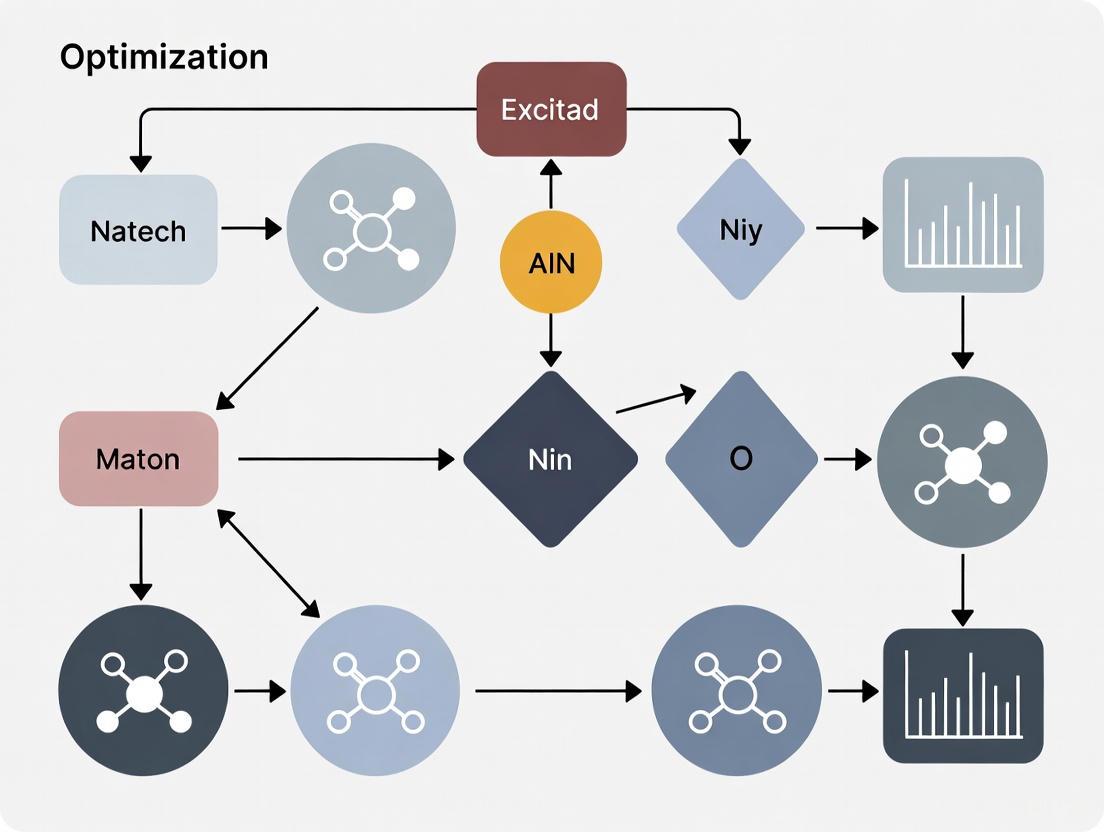

The workflow for this direct comparison is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (PALM) with a Photoconvertible FP

This protocol describes the use of the orange-to-far-red PSmOrange3 protein for single-molecule super-resolution imaging [5].

- Cell Preparation: Transfect mammalian cells (e.g., HeLa) with a PSmOrange3 fusion construct targeting your protein of interest (e.g., tubulin for microtubule imaging).

- Mounting: For live-cell PALM, use an imaging chamber with appropriate media. For fixed-cell PALM, fix cells with paraformaldehyde and mount with an antifade reagent.

- Image Acquisition on PALM Microscope:

- Initial Imaging: Take a low-resolution image using weak 550 nm light to locate the orange form of PSmOrange3.

- Photoconversion: Use a 488 nm or 455-490 nm blue light laser at moderate power to stochastically photoconvert a sparse subset of PSmOrange3 molecules from the orange to the far-red state.

- Localization: Image the photoconverted far-red molecules using a 614 nm laser until they bleach. Record thousands to tens of thousands of frames.

- Cycle: Repeat the photoconversion and localization cycles to build a complete dataset.

- Data Processing: Use PALM analysis software to precisely localize the center of each single-molecule emission event in every frame. Reconstruct a super-resolution image with a resolution of 20-30 nm.

The logical workflow for this super-resolution technique is as follows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Fluorescent Protein Imaging

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Antifade Mounting Media | Preserves fluorescence signal by reducing photobleaching during microscopy [7]. | Essential for fixed-cell super-resolution and long imaging sessions. |

| Neutral-Density (ND) Filters | Reduces the intensity of excitation light reaching the sample. | Crucial for minimizing photobleaching and phototoxicity in live-cell imaging [7] [8]. |

| Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibodies | Used in indirect immunofluorescence to detect primary antibodies with high specificity. | Minimizes background and cross-reactivity in multi-color staining experiments [6]. |

| TrueBlack Autofluorescence Quencher | Reduces lipofuscin-based tissue autofluorescence. | Particularly useful for imaging in the green channel and when working with archival tissue samples [6]. |

| Genome Editing Tools (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9) | Enables precise, single-copy insertion of FP tags into endogenous genomic loci. | Prevents non-physiological expression levels and artifacts from overexpression [4]. |

For researchers in bioimaging and drug development, achieving optimal signal from fluorescent proteins (FPs) is paramount. A fundamental principle governing this is the direct relationship between a protein's chromophore structure and its excitation maximum. The chromophore, a post-translationally modified tripeptide within the FP, is responsible for light absorption and emission. Its specific chemical structure dictates the energy required for electron excitation, thereby determining the peak excitation wavelength. Understanding this relationship is crucial for selecting the right FP for an application, designing multicolor experiments, and troubleshooting issues like weak signal or unexpected fluorescence. This guide provides a focused overview of chromophore structures and their direct impact on excitation properties to help you optimize your experimental outcomes.

FAQs: Chromophore Fundamentals

1. What is a chromophore and how does it determine the excitation wavelength of a fluorescent protein?

A chromophore is a molecule, or a region within a larger molecule, that absorbs specific wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation [9]. In fluorescent proteins, the chromophore is formed by an autocatalytic post-translational modification of three consecutive amino acids [10]. The observed color is the light that is not absorbed but is instead reflected or transmitted [9]. The excitation maximum is determined by the chromophore's electronic structure. Specifically, the energy difference between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO)—known as the HOMO-LUMO gap—defines the energy required to promote an electron to an excited state [9]. A larger conjugated π-electron system in the chromophore reduces this energy gap, resulting in the absorption of longer, lower-energy wavelengths of light [9].

2. Why do my red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) sometimes appear green during maturation, and how does this relate to the chromophore?

The temporary green fluorescence you observe is a known intermediate in the maturation pathway of many RFPs. Historically, it was believed that red chromophores formed directly through a green-emitting intermediate [11]. However, more recent research has uncovered that the dominant pathway for forming a DsRed-like chromophore occurs through a blue-absorbing TagBFP-like intermediate, not the GFP-like green form [11] [10]. The green form is now often considered a "dead-end" product or a minor pathway in some RFPs [11]. This process involves the stepwise extension of the chromophore's π-conjugation system, which progressively shifts the excitation and emission wavelengths to the red part of the spectrum.

3. I need a fluorescent protein with a very short excitation wavelength. What structural features should I look for?

Short-wavelength FPs are engineered by strategically modifying the chromophore's environment to produce a higher energy gap (HOMO-LUMO gap). Two key approaches are:

- Chromophore Hydration: The recently developed violet fluorescent protein "Sumire" (ex. 340 nm, em. 414 nm) utilizes a hydrated chromophore. The addition of a water molecule across the chromophore's double bond shortens the effective π-conjugation, leading to a very short emission wavelength [12].

- Blocking Excited-State Proton Transfer (ESPT): In proteins like mKalama1 and Sumire, mutations are introduced (e.g., T203V) to remove the ESPT pathway inherent to GFP. This traps the chromophore in a neutral state, resulting in blue-shifted emission compared to the anionic form [12].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly low fluorescence signal | The chosen excitation wavelength does not match the true excitation maximum of the FP. | Consult the FP's datasheet for its exact excitation peak. Perform an excitation scan to empirically determine the optimal wavelength for your specific setup. |

| No fluorescence after expression | Incomplete chromophore maturation. The protein may be folded, but the chromophore has not fully formed. | Ensure proper conditions for maturation (e.g., temperature, pH, presence of oxygen). Allow more time for maturation, especially for slow-maturing FPs like some RFPs. |

| Green emission from an RFP construct | The RFP is trapped in a green-emitting intermediate state or the maturation process is incomplete. | Increase incubation time post-expression. Check for mutations in the protein barrel that might disrupt the final oxidation step from a green to a red chromophore [11]. |

| Inconsistent excitation maxima between publications | Differences in environmental conditions (pH, temperature) or protein mutations affecting the chromophore's electronic state. | Standardize your experimental buffer conditions. Be aware that point mutations can fine-tune the chromophore's environment and alter its excitation properties. |

Quantitative Data: Fluorescent Protein Chromophore Properties

The table below summarizes the spectral characteristics of various FPs, organized by their chromophore class, to aid in your selection and troubleshooting.

Table 1: Spectral Properties of Key Fluorescent Proteins

| Protein | Chromophore Type | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Brightness* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TagBFP | TagBFP-like (Blue Intermediate) | 399 | 456 | 52,000 | 0.63 | 32.8 | [10] |

| Sumire | Hydrated YFP-type | ~340 | 414 | 20,000 | 0.70 | 14.0 | [12] |

| mTagGFP | GFP-like | 483 | 506 | 56,500 | 0.60 | 33.9 | [10] |

| mKO | Orange-type (Cyclized Lys65) | 551 | 563 | 105,000 | 0.61 | 64.0 | [10] |

| TagRFP-T | DsRed-like | 555 | 584 | 81,000 | 0.41 | 33.2 | [10] |

| mKate2 | DsRed-like | 588 | 633 | 62,500 | 0.40 | 25.0 | [10] |

| mNeptune | Far-red DsRed-like | 599 | 649 | 57,500 | 0.18 | 10.4 | [10] |

*Brightness is calculated as (Extinction Coefficient × Quantum Yield)/1000.

Experimental Protocols

Purpose: To empirically determine the optimal excitation wavelength for your FP construct in your specific experimental system, controlling for instrument variability and environmental factors.

Materials:

- Purified FP solution or cells expressing your FP construct.

- Spectrofluorometer or fluorescence microplate reader capable of wavelength scanning.

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4).

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a sample of your FP in a suitable buffer. For purified protein, use an OD280 or known concentration to ensure the signal is within the instrument's linear range. For cells, use a consistent number of transfected cells.

- Emission Wavelength Setting: Set the fluorometer to scan excitation wavelengths. First, find the approximate emission maximum by using a known excitation wavelength (e.g., 488 nm for GFP-like FPs) and performing an emission scan.

- Excitation Scan: Fix the emission monochromator at the emission maximum determined in step 2. Scan the excitation monochromator across a relevant range (e.g., 350-600 nm).

- Data Analysis: The peak of the resulting graph is the excitation maximum for your sample. Use this wavelength for all subsequent experiments for maximum signal intensity.

Protocol 2: Verifying Chromophore Maturation via Fluorescence Kinetics

Purpose: To troubleshoot issues of no or low fluorescence by confirming whether the chromophore has matured correctly.

Materials:

- Bacterial or eukaryotic culture expressing your FP.

- Fluorescence plate reader or time-lapse fluorescence microscope.

- Suitable growth media.

Method:

- Expression Induction: Induce expression of your FP in a bacterial culture or transfect eukaryotic cells.

- Continuous Monitoring: Immediately place the sample in a plate reader or microscope stage maintained at the appropriate growth temperature.

- Data Collection: Configure the instrument to take fluorescence readings (using the FP's known excitation/emission wavelengths) at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 minutes) over several hours to days.

- Interpretation: Plot fluorescence intensity over time. An increasing curve indicates successful chromophore maturation. The lack of an increase suggests a problem with folding, maturation, or protein expression. For RFPs, you may be able to monitor the initial appearance and subsequent disappearance of a blue or green intermediate [11].

Visualizing Chromophore Formation Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the formation of red fluorescent protein chromophores, a common source of troubleshooting issues.

RFP Chromophore Maturation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key materials and their functions for experiments involving fluorescent protein chromophores.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for FP Chromophore Research

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cloning Vector (e.g., pBAD, pET) | Controls the expression level of the FP, which can affect folding and maturation kinetics. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents degradation of expressed FPs during extraction and purification. |

| Oxygen-Rich Culture Conditions | Essential for the oxidation steps required for chromophore formation in almost all FPs. |

| Spectrofluorometer | Key instrument for measuring excitation/emission spectra and quantifying fluorescence intensity. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography | Purifies properly folded, soluble FP from aggregates and misfolded proteins that will not fluoresce. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Analyzes the precise mass of the chromophore and its intermediates, confirming chemical structure [11]. |

This technical support article elucidates the fundamental molecular interactions—specifically hydrogen bonding and π-orbital conjugation—that induce red-shifting in fluorescent spectra. Intended for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide provides detailed troubleshooting advice and experimental protocols to help optimize excitation wavelengths and emission properties for a wide range of fluorescent proteins and synthetic systems. By exploring both theoretical principles and practical applications, we aim to support advanced research in bioimaging, biosensing, and drug discovery.

Core Scientific Principles: Why Red-Shifting Occurs

What are the key molecular interactions that cause a red shift in fluorescence spectra? A red shift (or bathochromic shift) refers to the movement of a fluorescence emission peak to a longer, lower-energy wavelength. This phenomenon is primarily driven by two key molecular interactions:

- Hydrogen Bonding: The formation of hydrogen bonds between a fluorophore and its surrounding environment can stabilize the excited state more than the ground state. This reduced energy gap between the ground and excited states results in the emission of lower-energy (longer wavelength) photons [13] [14]. In certain systems, thermally-driven rearrangement of hydrogen bonds can induce a conformational change that leads to the formation of a donor-acceptor structure, significantly red-shifting the emission [13].

- π-Orbital Conjugation and Through-Space Interactions: Extending the system of conjugated π-electrons, either through chemical synthesis or through-space interaction (TSI) of clustered electron-rich groups (e.g., carbonyls, amides), creates greater electron delocalization. This delocalization lowers the energy required for the π→π* transition, leading to red-shifted emission [13] [15]. This is the principle behind Clustering-Triggered Emission (CTE).

The following diagram illustrates how these interactions collectively influence the electronic structure of a fluorophore to produce a red-shift.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I intentionally induce a red shift in my hydrogel system?

Issue: A researcher is working with a blue-fluorescent poly(N-acryloylsemicarbazide) (PNASC) hydrogel and wants to shift its emission to the red for better tissue penetration in imaging applications.

Solution: A thermodynamically driven strategy can be employed to achieve this shift [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Preparation: Synthesize the PNASC hydrogel using N-acryloylsemicarbazide (NASC) monomer and a photoinitiator like LAP in a water/DMSO solvent mixture. Cure the precursor with 405 nm light [13].

- Thermal Treatment: Soak the equilibrated hydrogel in deionized water. Instead of maintaining it at room temperature, place it in a hot water bath at a temperature between 85°C and 100°C for 48 hours [13].

- Mechanism: The heat provides energy for polymer chains to reconform. The strong, multiple hydrogen-bonding groups (urea) form denser hydrophobic clusters by creating stronger intra- and inter-chain hydrogen bonds. This process squeezes out water molecules that were hydrating and disrupting these clusters, enhancing through-space π-orbital interactions among the electron-rich groups. The resulting enhanced electron delocalization creates a new chromophore with a lower energy gap, emitting red light [13].

- Verification: Confirm the red shift using fluorescence spectroscopy. The hydrogel should show new emission peaks at ~610 nm when excited at ~365 nm or ~530 nm [13].

FAQ 2: My fluorescent protein fusion is not localizing correctly. Could the tag itself be the problem?

Issue: A scientist observes abnormal localization or function of their protein of interest after fusing it with a fluorescent protein (FP) tag.

Solution: The FP tag can indeed interfere with the natural function and localization of the target protein. Below is a troubleshooting workflow to diagnose and resolve this issue.

Additional Troubleshooting Steps:

- Pilot with EGFP/mEmerald: Before tagging your protein, conduct a pilot study using a well-characterized FP like EGFP or the brighter mEmerald to verify correct spatial expression and function [16].

- Internal Fusion: If both termini are critical, consider inserting the FP into a flexible loop or disordered region within the target protein sequence [16].

FAQ 3: I am getting no signal or a very weak signal from my fluorescent protein. What could be wrong?

Issue: After transfection and expression, the fluorescence signal from the FP is undetectable or too low for reliable imaging.

Solution: This is a common problem with multiple potential causes [16] [6].

- Cause 1: Low Expression or Improper Chromophore Maturation.

- Action: Verify protein expression via Western blot. Ensure your cells are healthy and the transfection was efficient. Remember that chromophore maturation can take several hours after protein synthesis [17].

- Action: Check that your vector has a strong, appropriate promoter and that the FP cDNA is codon-optimized for your host system (e.g., mammalian, plant) [16].

- Cause 2: Incorrect Microscopy Setup.

- Action: Double-check that you are using the correct excitation wavelength and emission filter for your specific FP. A standard FITC filter set may not be optimal for all GFP variants [17].

- Cause 3: Quenching due to Environmental Factors.

- Action: If your target protein localizes to an acidic compartment (e.g., lysosomes, secretory granules), the fluorescence of many FPs (like EGFP and EYFP) is quenched. Use an FP with a lower pKa, such as those derived from corals (e.g., mCherry), which are more stable in acidic environments [16] [17].

- Cause 4: Photobleaching.

FAQ 4: How can I use hydrogen bond design principles to predict the stability of a fluorophore complex?

Issue: A researcher wants to design a supramolecular sensor where a host molecule recognizes a specific guest via hydrogen bonding, and the interaction produces a fluorescent signal.

Solution: The stability of such complexes is governed by predictable hydrogen bond design principles [14].

Key Design Principles:

- Electronegativity and pKa Matching: Stronger hydrogen bonds form between the best donor (most acidic X-H) and the best acceptor (most basic Y). A good match between the donor pKa and acceptor pKa can lead to very strong, low-barrier hydrogen bonds [14].

- Secondary Electrostatic Interactions: In multi-point hydrogen-bonding systems, the stability is enhanced if additional donor-acceptor pairs reinforce each other (e.g., as in adenine-thymine base pairing). Repulsive interactions between like charges can decrease stability [14].

- Resonance-Assisted Hydrogen Bonding (RAHB): If the hydrogen bond is part of a conjugated π-system (e.g., in a β-diketone), the bond strength is significantly enhanced due to electron delocalization [14].

- Cooperativity: A network of hydrogen bonds (e.g., as in water or protein α-helices) is stronger than the sum of individual bonds, leading to increased complex stability [14].

Quantitative Data and Reagent Toolkit

Table 1: Spectral Properties of Selected Far-Red and Red Fluorescent Proteins

This table provides a comparison of engineered fluorescent proteins with emissions in the red and far-red spectrum, useful for deep-tissue imaging. Data is compiled from literature [18].

| Fluorescent Protein | Quaternary Structure | Excitation Peak (nm) | Emission Peak (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (mM⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Relative Brightness* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DsRed | Tetramer | 558 | 583 | 75 | 0.79 | 59.3 |

| mCherry | Monomer | 587 | 610 | 72 | 0.22 | 15.8 |

| mRaspberry | Monomer | 598 | 625 | 86 | 0.15 | 12.9 |

| mPlum | Monomer | 590 | 649 | 41 | 0.10 | 4.1 |

| mKate2 | Monomer | 586 | 630 | 50 | 0.36 | 18.0 |

| mNeptune | Monomer | 600 | 650 | 67 | 0.20 | 13.4 |

| mCardinal | Monomer | 604 | 659 | 87 | 0.19 | 16.5 |

| E2-Crimson | Tetramer | 611 | 646 | 59 | 0.12 | 7.1 |

Note: *Relative Brightness is calculated as (Extinction Coefficient x Quantum Yield) relative to DsRed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key reagents and materials used in experiments involving hydrogen bonding, π-interactions, and fluorescent proteins.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| N-Acryloylsemicarbazide (NASC) | A monomer with strong multiple hydrogen-bonding urea groups [13]. | Synthesis of supramolecular PNASC hydrogels for thermodynamically induced red-shifting studies [13]. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A photoinitiator for UV/blue light-induced polymerization [13]. | Initiating free-radical polymerization for hydrogel formation under 405 nm light [13]. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [C8MIM]NTf2) | Solvents that promote dissolution via hydrogen-bonding and π-π interactions [15]. | Dissolving insoluble conjugated molecules like pentacene for solution-processable sensors [15]. |

| Codon-Optimized Vectors | Plasmid vectors with FP genes optimized for translation in specific host systems (e.g., mammalian, bacterial) [16]. | Enhancing expression levels of FP-fusion proteins in the target organism to improve signal [16]. |

| Monomeric FP Variants (e.g., mCherry, mNeptune) | Engineered FPs that do not self-associate, preventing aggregation and mislocalization [18] [16]. | Creating FP-fusions where oligomerization would disrupt the function or localization of the target protein [16]. |

| Flexible Glycine Linkers | Short sequences of glycine amino acids providing flexibility between fused protein domains [16]. | Connecting an FP to a target protein to ensure both domains fold correctly and independently [16]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "optical window" in biological imaging? The "optical window" refers to specific ranges of light wavelengths, primarily in the near-infrared (NIR) spectrum, where biological tissues are most transparent. This transparency occurs because key tissue components like hemoglobin, melanin, and water absorb light very weakly in these regions. The most prominent windows are the first NIR window (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) and the second NIR window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm). Imaging within these windows allows light to penetrate deeper into tissue with less scattering and absorption, enabling visualization of structures beneath the surface [19] [20].

Q2: Why do longer wavelengths, like those in the NIR-II window, provide better images? Longer wavelengths provide superior images for two main physical reasons:

- Reduced Scattering: Photon scattering in tissue nearly scales with λ–α, where λ is the wavelength. Longer-wavelength light possesses a lower scattering coefficient, meaning it is deflected less often as it passes through tissue. This reduction in scattering preserves the direction of the light, preventing image blur and allowing for higher-resolution images from greater depths [19].

- Lower Autofluorescence: Biological molecules naturally absorb and emit light in the visible spectrum (350-700 nm), creating a bright background "noise". In the NIR windows, this natural tissue autofluorescence is significantly dimmed. The result is a much higher signal-to-background ratio, leading to cleaner, higher-contrast images [20].

Q3: How does the NIR-II window compare to the NIR-I window? While the NIR-I window (700-900 nm) already offers advantages over visible light, the NIR-II window (1000-1700 nm) provides further enhancements. Research shows that within the NIR-II region, benefits are amplified: light can penetrate two times deeper, and image resolution can be two to three times clearer than with NIR-I light [20]. Furthermore, emerging studies are exploring sub-windows beyond 1700 nm (e.g., 1700-2080 nm), where a unique combination of low scattering and moderate water absorption can yield even higher contrast for specific tissues like adipose tissue [21].

Q4: Are there any disadvantages to using longer wavelengths for imaging? The primary challenge is the availability of bright, biocompatible probes (fluorophores) that operate efficiently in these ranges. While traditional fluorescent proteins like GFP are bright in the visible spectrum, engineering molecular fluorophores and fluorescent proteins that are bright and stable in the NIR-II window is an active area of research [19] [20]. Additionally, imaging in regions with strong water absorption (e.g., around 1450 nm or 1930 nm) requires exceptionally bright probes to overcome signal attenuation, though this same absorption can be harnessed to improve image contrast by suppressing background signals [21].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Deep-Tissue Images

Symptoms: Images are noisy, with weak fluorescence signals from the target that are difficult to distinguish from background tissue autofluorescence.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Excitation Wavelength | Shift excitation and emission to a longer-wavelength window (e.g., NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm) [19]. | Verify that your fluorophore is bright in the desired NIR window. The miRFP718nano protein, for instance, is engineered for this purpose [20]. |

| High Tissue Scattering | Utilize the NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm) or NIR-IIc (1700-1880 nm) sub-windows for superior scattering suppression [19] [21]. | Ensure your detector is sensitive in these longer wavelength ranges. |

| Probe is Not Bright Enough | Use fluorophores with high quantum yield and large absorption cross-section. Consider bright quantum dots (e.g., PbS/CdS QDs) for NIR-II imaging [21]. | Balance brightness with biocompatibility and potential toxicity, especially for in vivo applications. |

Problem: Rapid Photobleaching or Cell Weakening

Symptoms: The fluorescence signal fades quickly during imaging, or the living cells being imaged show signs of stress or death.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Light is Too Intense | Reduce the intensity of the excitation light and increase the camera's exposure time or sensitivity to compensate [22]. | Use a high-sensitivity cooled camera to detect weaker signals with low noise [22]. |

| Visible Light Excitation | Switch to NIR excitation light. The lower energy photons are less phototoxic and cause less damage to living cells [19] [23]. | This directly addresses the root cause of phototoxicity while also improving penetration. |

| Fluorophore is Not Stable | Select fluorophores known for high photostability, such as certain Janelia Fluor rhodamine derivatives or other engineered NIR dyes [19]. | Check the literature for photostability metrics (e.g., peak molecular brightness) under two-photon excitation [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists essential tools for designing experiments in the NIR optical windows.

| Item | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Molecular Fluorophores | Organic dyes that absorb and emit light within the NIR-II window; often designed as donor-acceptor charge transfer dyes [19]. | Linear (one-photon) in vivo imaging of blood flow or tumor targeting [19]. |

| Engineered NIR Fluorescent Proteins | Genetically encoded proteins, like miRFP718nano, that bind biliverdin in mammalian tissues to emit NIR light [20]. | Labeling and tracking specific cell types (e.g., cancer cells) or gene expression in live animal models [20]. |

| PbS/CdS Quantum Dots (QDs) | Nanocrystals with bright, tunable fluorescence emission at long wavelengths (e.g., beyond 1500 nm) [21]. | High-contrast vascular imaging in the 1880-2080 nm window; used where extreme brightness is needed [21]. |

| Target-Specific Conjugates | Fluorophores (e.g., HLF647, ICG) chemically linked to targeting molecules like antibodies (e.g., Trastuzumab) [23]. | Targeted photodynamic therapy (PDT) and molecular imaging of specific cancer biomarkers (e.g., HER-2) [23]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluating Wavelength-Dependent Imaging Depth and Contrast

This protocol outlines a methodology for comparing the efficacy of different imaging windows, as referenced in studies of NIR-II imaging [19] [21].

- Probe Selection: Select a bright, photostable fluorophore with a wide emission profile, such as PbS/CdS core-shell quantum dots, which emit brightly across multiple NIR-II sub-windows [21].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a tissue phantom that mimics the scattering and absorption properties of real tissue. Alternatively, use an in vivo model, such as a mouse with a xenograft tumor.

- Image Acquisition: Use a microscopy or imaging system equipped with a tunable laser and a sensitive NIR detector (e.g., an InGaAs camera). Acquire images of the same region of interest using different emission filters to collect signal from specific sub-windows (e.g., NIR-IIa: 1300-1400 nm, NIR-IIb: 1500-1700 nm, NIR-IIx: 1400-1500 nm) [21].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) and the Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) for each acquired image. Monte Carlo simulations can be used in parallel to model photon propagation and validate experimental results [21].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Targeted Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) Using NIR Probes

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing red and NIR photodynamic therapy [23].

- Conjugate Preparation: Conjugate a targeting antibody (e.g., Trastuzumab for HER-2) to a NIR photosensitizer dye (e.g., Indocyanine Green, ICG) using a commercial labeling kit.

- Cell Line & Animal Model: Culture cancer cells expressing the target antigen (e.g., HER-2 positive A4 cells). Establish a xenograft tumor model by subcutaneously injecting these cells into immunodeficient mice.

- Probe Administration & Targeting: Intravenously inject the antibody-dye conjugate into the tumor-bearing mice. Allow sufficient time (e.g., 24-48 hours) for the conjugate to accumulate in the target tumor.

- Light Irradiation: Anesthetize the mouse and expose the tumor region to the appropriate NIR laser light (e.g., 808 nm for ICG) at a predetermined power and energy density.

- Efficacy Assessment:

- Tumor Volume: Monitor and measure tumor volume changes over time.

- Histology: After the experiment, excise tumors, section them, and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) to analyze necrosis-associated features.

- Necrotic Depth: Administer a fluorescent necrosis marker (e.g., AF546-pHLIP) to approximate the depth of laser light penetration and treatment effect [23].

Light-Tissue Interaction and the Optical Window

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of why longer wavelengths penetrate tissue more effectively.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) are indispensable tools in biological research, enabling the visualization of cellular processes in real time. A significant challenge in the field has been extending the palette of FPs to shorter wavelengths. Traditional approaches to creating blue and cyan variants primarily relied on substituting the tyrosine at position 66 in the chromophore with other aromatic amino acids like tryptophan or histidine. However, this method is limited by the number of available natural aromatic amino acids. A novel strategy, which involves the controlled hydration of the chromophore within its protein pocket, has recently enabled the development of violet-emitting proteins like "Sumire," which emits at 414 nm—the shortest emission wavelength reported for any fluorescent protein to date [12]. This technical support center provides a comprehensive guide to understanding, working with, and troubleshooting experiments involving these innovative hydrated chromophores.

FAQ: Understanding Hydrated Chromophores and Sumire

Q1: What is a hydrated chromophore, and how does it achieve a shorter emission wavelength? A hydrated chromophore is formed when a water molecule is chemically added across a double bond in the chromophore's structure. This hydration reaction shortens the π-conjugated system of the chromophore. In simpler terms, it reduces the extent of the electron cloud that absorbs and emits light, which results in a higher energy (shorter wavelength) of fluorescence emission. In the case of Sumire, this process yields violet fluorescence at 414 nm [12].

Q2: Why choose Sumire over other short-wavelength fluorescent proteins like Sirius? Sumire offers two key advantages over previously available short-wavelength FPs like Sirius:

- Shorter Emission Wavelength: Its 414 nm emission is the shortest of any available FP.

- Increased Brightness: The calculated fluorescence brightness of Sumire is approximately 3.9 times higher than that of Sirius. In live HeLa cells, Sumire showed 3.3 times brighter emission than Sirius [12]. This combination makes Sumire a superior donor for FRET probes.

Q3: My hydrated chromophore protein is not fluorescing. What could be wrong? Several factors could be at play:

- Disrupted Hydrogen-Bond Network: The hydrogen-bond network involving water molecules and surrounding amino acids is crucial for stabilizing the hydrated chromophore and triggering its fluorescence. Mutations or improper folding that disrupt this network can quench emission [24].

- Unstable Chromophore State: The balance between the hydrated, neutral, and ionized chromophore states is sensitive to the protein environment. Mutations at key positions (like Q69 in the sfGFP scaffold) are necessary to stabilize the hydrated form over others [12].

- Low pH: While Sumire has a low pKa (3.8) and is stable over a wide pH range (5.5-9.0), its precursor variants (VFP0, VFP1) show strong pH dependence. Ensure your experimental pH is appropriate [12].

Q4: Can I create a FRET probe with Sumire? Yes, Sumire is an excellent FRET donor for acceptors that absorb at longer wavelengths, such as T-Sapphire. The spectral overlap between Sumire and T-Sapphire is 1.8 times larger than the pair of Sirius and T-Sapphire. The calculated Förster distance (R0) for the Sumire-T-Sapphire pair is 4.0 nm, which is longer than the 3.0 nm for the Sirius-based pair, indicating a more efficient energy transfer [12]. This allows for the creation of color variants of existing CFP-YFP FRET indicators for multi-parameter analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low Fluorescence Intensity in Expressed Sumire Variants

| Possible Cause | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Chromophore Maturation | Check time-dependence of fluorescence after protein expression. | Allow more time for chromophore folding and oxidation at proper temperature (e.g., 4°C overnight). |

| Disrupted ESPT Pathway | Review mutation plan; the T203V and S205V mutations are critical to block the excited-state proton transfer pathway that causes a red shift. | Verify the presence of T203V and S205V (or equivalent) mutations in your construct [12]. |

| Unstable Hydrated Chromophore | Check if stabilizing mutations (e.g., Q69A, V224R, H148G in the sfGFP scaffold) are present. | Introduce mutations that stabilize the hydrated form and improve quantum yield [12]. |

Issue 2: Unexpected Fluorescence Wavelength or Multiple Peaks

| Possible Cause | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed Chromophore States | Perform a full absorption scan. Multiple peaks near 350 nm (hydrated), ~395 nm (neutral), and ~490 nm (ionized) indicate a mixture. | Introduce mutations that favor the hydrated state (e.g., Q69A) to eliminate absorption from neutral and ionized forms [12]. |

| Cellular Environment Interference | Measure fluorescence in different pH buffers. | Use a protein with a low pKa and stable over a wide pH range, like Sumire (pKa 3.8), for intracellular experiments [12]. |

| Incorrect Protein Folding | Run an SDS-PAGE gel to check for proper protein size and oligomeric state. | Optimize expression conditions (temperature, inducer concentration) and consider using a more stable FP scaffold. |

Key Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: In Vitro Characterization of Hydrated Chromophore Proteins

Objective: To purify and characterize the spectral properties of a novel hydrated chromophore FP.

Materials:

- Expression System: E. coli strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)) transformed with plasmid encoding the FP.

- Chromophore: The necessary bilin precursor if using CBCRs (e.g., phycocyanobilin) [25].

- Buffers: Lysis buffer, purification buffers (e.g., for His-tag purification), and storage buffer.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer, fluorometer, pH meter.

Method:

- Protein Expression and Purification: Induce expression in E. coli with IPTG. Lyse cells and purify the protein using affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins).

- Absorption Spectroscopy: Measure the absorption spectrum from 250 nm to 600 nm. Identify peaks for the hydrated chromophore (~340 nm for Sumire), neutral chromophore (~395 nm), and ionized chromophore (~490 nm) [12].

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Record the emission spectrum by exciting at the hydrated chromophore's absorption peak (e.g., 340 nm). The emission peak for Sumire is at 414 nm.

- pH Stability Assay: Dialyze the purified protein against buffers of varying pH (e.g., pH 4.0 to 10.0). Measure fluorescence intensity at each pH to determine the pKa and operational range.

- Quantum Yield and Extinction Coefficient: Determine using standard comparative methods with appropriate reference fluorophores.

Protocol 2: Developing a FRET Biosensor Using Sumire

Objective: To create a FRET-based calcium indicator (e.g., vgCam) using Sumire as the donor and T-Sapphire as the acceptor.

Materials:

- Donor/Acceptor FPs: Genes for Sumire and T-Sapphire.

- Sensing Domain: The calcium-binding domain from a known indicator (e.g., calmodulin and M13 peptide from yellow cameleon).

- Cloning System: Appropriate molecular biology reagents.

Method:

- Vector Construction: Substitute the donor and acceptor in an existing FRET sensor (e.g., YC3.60) with Sumire and T-Sapphire, respectively. Remove 11 C-terminal amino acids from the donor to optimize the signal change rate [12].

- Expression and Testing: Express the recombinant biosensor (e.g., vgCam) in cells or purify it.

- Ratiometric Measurement: Excite at 350 nm (Sumire's excitation) and collect emission at both 414 nm (donor) and 510 nm (acceptor). The ratio of 510 nm/414 nm will change with calcium concentration. For vgCam, a 2.4-fold change in this ratio was observed with and without Ca²⁺ [12].

- Multiparameter Imaging: Co-express with another FRET probe (e.g., CFP-YFP based ATeam for ATP). Use 350 nm light to excite vgCam and 440 nm light to excite the CFP-based probe independently [12].

Data Presentation: Key Properties of Short-Wavelength FPs

Table 1: Spectral Properties of Short-Wavelength Fluorescent Proteins

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation Peak (nm) | Emission Peak (nm) | Molar Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Brightness Relative to Sirius | pKa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sumire | 340 | 414 | 2.0 × 10⁴ | 0.70 | ~3.9x | 3.8 |

| Sirius | ~355 | ~424 | 1.5 × 10⁴ | 0.24 | 1.0 (Reference) | ~4.5 - 6.0 |

| mKalama1 | ~385 | ~456 | 4.1 × 10⁴ | 0.45 | N/A | N/A |

| bfVFP | 323 | 430 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Data adapted from Sumire characterization [12].

Table 2: The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Hydrated Chromophore Work

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Superfolder GFP (sfGFP) Scaffold | A highly stable mutant of GFP used as a starting template for protein engineering. | Served as the structural backbone for developing Sumire [12]. |

| PSmOrange Protein/Crystals | A photoswitchable FP with high water content, useful for studying water's role in fluorescence. | Used as a model to experimentally demonstrate water-triggered low-wavelength emission [24]. |

| Dreiklang Mutant | A reversibly photoswitchable FP whose mechanism involves light-induced chromophore hydration. | Computational model for studying the hydration/dehydration reaction pathway [26]. |

| Hexamethylindotricarbocyanine-based LS482 | A near-infrared pH-sensitive fluorescence lifetime molecular probe. | Useful for pH sensing in physiological ranges, especially in deep tissue [27]. |

| BCECF, AM ester | A widely used, cell-permeant fluorescent indicator for estimating intracellular pH. | Determining the pH of intracellular compartments like the cytosol [28]. |

Visualization: Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Sumire Protein Engineering Pathway

Diagram 2: Chromophore States and Spectral Signatures

Strategic Wavelength Selection for Biosensors, FRET, and Live-Cell Imaging

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a physical phenomenon used as a powerful tool in biomedical research for estimating nanometer-scale distances between biological molecules. This through-space, photon-less energy transfer process between a donor fluorophore and an acceptor chromophore functions as a "molecular ruler" that can resolve intermolecular distances from 1 to 10 nanometers. The efficiency of this energy transfer is inversely proportional to the sixth power of the distance between donor and acceptor, making FRET extremely sensitive to small changes in distance. When applied to fluorescent proteins (FPs), FRET enables researchers to visualize dynamic protein interactions and conformational changes in living cells under physiological conditions.

Key Factors in FRET Pair Design

The Critical Role of Spectral Overlap

The fundamental mechanism of FRET involves a donor fluorophore in an excited electronic state that transfers its excitation energy to a nearby acceptor fluorophore through non-radiative dipole-dipole interactions. Efficient transfer requires a significant spectral overlap between the donor emission and the acceptor absorption spectra, as this overlap indicates that the energy liberated when an excited donor transitions to its ground state is equivalent to the energy required to excite an acceptor.

The overlap integral (J) quantifies this spectral compatibility and is calculated as:

J = ∫FD(λ)εA(λ)λ⁴dλ

Where FD(λ) is the normalized emission spectrum of the donor, εA(λ) is the extinction coefficient of the acceptor, and λ is the wavelength. A larger overlap integral value indicates better energy transfer potential between the FRET pair [29] [30].

Understanding the Förster Distance (R₀)

The Förster distance (R₀) represents the characteristic distance at which the FRET efficiency is 50% and is a key parameter for evaluating FRET pair performance. This distance is calculated using the equation:

R₀⁶ = (8.785 × 10⁻⁵ × κ² × QD × J)/n⁴

Where:

- κ² is the orientation factor between donor and acceptor dipoles (typically assumed to be 2/3 for dynamic averaging)

- QD is the quantum yield of the donor

- J is the spectral overlap integral

- n is the refractive index of the medium [29] [31]

The actual FRET efficiency (E) at a specific distance (r) is then described by:

E = 1/[1 + (r/R₀)⁶] [32]

This inverse sixth-power relationship makes FRET efficiency highly sensitive to distance changes near R₀, enabling precise distance measurements in the 1-10 nm range.

Optimizing FRET Pair Selection

Key Considerations for Fluorescent Protein Pairs

For live-cell imaging, genetically encoded fluorescent proteins are preferred donors and acceptors. The currently preferred fluorescent proteins for FRET analysis are Aequorea victoria jellyfish GFP derivatives featuring cyan and yellow emission (ECFP and EYFP) as donors and acceptors, respectively. However, several newer and more advanced variants have proven highly effective in providing increased dynamic range for monitoring sensitive FRET signals [32].

When selecting FP pairs, consider these critical factors:

- Spectral Overlap: Ensure substantial overlap between donor emission and acceptor absorption spectra while minimizing direct acceptor excitation at donor excitation wavelengths [33] [32].

- Brightness Matching: Fluorophores with comparable brightness yield more satisfactory results as significant mismatches can lead to detector saturation with one signal while the other is lost in noise [32].

- Maturation Rates: Match the relative maturation rates of donor and acceptor FPs. FRET measurements will be compromised if one FP matures substantially faster than the other [32].

- Photostability: Consider resistance to photobleaching, especially for long-term time-lapse experiments [33].

- Orientational Freedom: Unlike small organic fluorophores, FPs have rotational correlation times typically much longer than their fluorescence lifetime, making them virtually static during their excited state. This affects the κ² value used in distance calculations [31].

Quantitative Comparison of Common FRET Pairs

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Fluorescent Protein FRET Pairs

| Donor | Acceptor | Förster Distance (R₀) | Spectral Overlap Integral (J) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP | EYFP | ~4.9-5.2 nm | Moderate | Well-characterized, widely used | Moderate dynamic range, significant spectral bleed-through |

| Cerulean | Venus | ~5.3-5.6 nm | High | Improved quantum yield (Cerulean) and extinction coefficient (Venus) | Still substantial spectral overlap challenges |

| mTurquoise2 | sYPet | ~5.7 nm | Very High | High brightness and photostability, excellent for sensitive detection | Requires careful control of expression levels |

| CFP | YFP | ~4.7-5.0 nm | Moderate | Historical standard, readily available | Suboptimal compared to newer variants |

| GFP | RFP | Variable | Low to Moderate | Enables multiplexing with CFP/YFP sensors | Often smaller R₀ values |

Experimental Protocols for FRET Validation

Implementing Essential Control Samples

Proper controls are essential to confirm that observed changes in donor and acceptor emission arise from FRET rather than other processes. The minimum control samples include [33]:

- Donor-only sample: Expressing only the donor FP to establish baseline donor emission and detect donor spectral bleed-through (DSBT) into the acceptor channel.

- Acceptor-only sample: Expressing only the acceptor FP to measure direct acceptor excitation (acceptor spectral bleed-through, or ASBT) at the donor excitation wavelength and ensure acceptor emission is specifically from FRET-sensitized emission.

- No-FRET reference: A sample with both donor and acceptor but with disrupted proximity to guard against trivial energy transfer via reabsorption.

Measurement Modalities and FRET Metrics

Different FRET measurement approaches offer distinct advantages:

- Sensitized Emission FRET: Measures acceptor emission following donor excitation. While most accessible, it requires careful correction for spectral bleed-through [29] [34].

- Acceptor Photobleaching FRET (apFRET): Determines FRET efficiency by comparing donor fluorescence before and after photobleaching the acceptor. This method is among the most accurate but cannot be repeated on the same cell [35] [29].

- Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM-FRET): Measures the decrease in donor fluorescence lifetime in the presence of FRET. This method avoids spectral bleed-through issues but requires specialized equipment [35] [29] [33].

- Spectral FRET Imaging: Uses linear unmixing algorithms to separate contributions from donor, acceptor, and FRET signals across wavelength bands, providing more robust bleed-through correction [35] [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common FRET Experimental Issues

FAQ: Addressing Spectral Bleed-Through

Q: What is spectral bleed-through and how can I minimize its impact on my FRET measurements?

A: Spectral bleed-through occurs when donor emission leaks into the acceptor detection channel (donor bleed-through) or when the excitation light directly excites the acceptor (acceptor bleed-through). To address this [35] [32]:

- Select optimized filter sets that maximize separation between donor and acceptor emission peaks.

- Use spectral unmixing algorithms to mathematically separate the contaminating signals from the true FRET signal.

- Implement control experiments with donor-only and acceptor-only samples to quantify bleed-through coefficients for correction.

- Consider FRET pairs with larger spectral separation (e.g., blue-red pairs rather than cyan-yellow), though this often comes at the cost of reduced FRET efficiency.

FAQ: Dealing with Low FRET Efficiency

Q: My FRET biosensor shows very low efficiency changes even when I know the molecular interaction is occurring. What could be wrong?

A: Low dynamic range in FRET biosensors can result from several factors [33] [32]:

- Suboptimal linker design: The peptide linkers between FPs and your biosensor elements may be too rigid or too flexible, preventing proper conformational changes.

- Incorrect orientation: The relative orientation of donor and acceptor FPs may be unfavorable (κ² << 2/3). Try different fusion positions or incorporate flexible linkers.

- Mismatched maturation rates: If one FP matures significantly slower than the other, you'll have non-fluorescent proteins that don't participate in FRET.

- Excessive expression levels: High concentrations can cause non-specific aggregation and background FRET.

FAQ: Ensuring Accurate Distance Measurements

Q: Can I reliably calculate distances between FPs using FRET efficiency measurements?

A: While FRET is famously called a "molecular ruler," estimating precise distances between FPs requires careful consideration of orientation factors. Unlike small organic fluorophores, FPs rotate slowly compared to their fluorescence lifetime, making the standard assumption of κ² = 2/3 potentially problematic [31]. For more accurate distance estimates:

- Use the static random isotropic model rather than the dynamic averaging model for FPs

- Consider using Monte Carlo simulation-generated lookup tables to relate FRET efficiency to distance

- Interpret calculated distances as estimates rather than precise measurements, acknowledging potential orientation constraints

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for FRET Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in FRET Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| FRET Standard Plasmids | C5V, CVC, VCV, CTV constructs [35] | Positive and negative controls with known FRET efficiencies for system calibration and validation. |

| Optimized Donor FPs | Cerulean, mTurquoise2, ECFP [35] [32] | High quantum yield donors that increase Förster distance and FRET efficiency. |

| Optimized Acceptor FPs | Venus, Citrine, sYPet, EYFP [35] [32] | Acceptors with high extinction coefficients that improve energy transfer acceptance. |

| Protease Cleavage Sensors | Caspase cleavage site linkers [32] | Validation tools with high dynamic range for testing new FRET pairs or microscope systems. |

| Calibration Standards | FRET-ON and FRET-OFF constructs [34] | Barcoded standards for normalizing FRET ratios across different imaging sessions and conditions. |

| Spectral Unmixing Algorithms | Linear unmixing, processed FRET (PFRET) [35] | Computational tools for removing contaminating background from DSBT and ASBT in FRET images. |

Visualizing FRET Workflows and Relationships

FRET Mechanism and Experimental Setup

FRET Experimental Optimization Workflow

Genetically encoded biosensors are indispensable tools in modern cell biology, allowing researchers to monitor signaling molecules and metabolites in living cells with high spatiotemporal resolution. These biosensors primarily function by coupling a sensing unit that detects a specific analyte or enzymatic activity to a reporting unit that produces a fluorescent readout. The two predominant designs are Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based biosensors and intensiometric biosensors, which differ fundamentally in their operational principles and experimental requirements [36].

FRET-based biosensors rely on the distance-dependent energy transfer between two fluorophores—a donor and an acceptor. When the biosensor undergoes a conformational change in response to the target, it alters the distance or orientation between these fluorophores, changing the FRET efficiency. This change is typically measured as a ratio of donor to acceptor emission, providing an internal reference that makes the measurement largely independent of biosensor concentration [36] [37]. In contrast, intensiometric biosensors typically utilize a single fluorophore or a dimerization-dependent fluorescent pair, where the target-induced conformational change directly modulates the fluorescence intensity [36] [38]. Understanding these fundamental differences is critical for selecting the appropriate biosensor for specific experimental contexts, particularly when considering excitation requirements and compatibility with other optical components.

Technical Comparison: Operating Principles and Performance

The choice between intensiometric and FRET-based biosensors involves trade-offs across multiple performance parameters. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of their key characteristics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of FRET-based and Intensiometric Biosensors

| Feature | FRET-Based Biosensors | Intensiometric Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Reporting Mechanism | Two fluorophores; rationetric measurement of FRET efficiency [36] [37] | Single fluorophore or ddFP pair; change in fluorescence intensity [36] [38] |

| Typical Dynamic Range | Moderate (~80% change in PercevalHR [39]) | Often high (e.g., 350%-390% for MaLions [39]; ~24.6-fold for G-KRas [38]) |

| Excitation Requirements | Multiple excitation wavelengths for donor and acceptor [37] | Often single excitation wavelength [38] |

| Key Advantage | Ratiometric output corrects for concentration, focus drift [37] [40] | Higher sensitivity and faster kinetics in some cases [38] |

| Key Disadvantage | Spectral cross-talk requires correction; more complex analysis [37] [41] | Sensitive to variations in expression level and focus [38] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Limited by broad emission spectra [38] | Higher, especially with red-shifted variants [36] [38] |

| Example Biosensors | ATeams (ATP) [39], ECATS2 (extracellular ATP) [40], PercevalHR (ATP/ADP) [39] | G-/R-KRas, Rac1, Cdc42 (small GTPases) [38], iATPSnFRs (ATP) [39], MaLions (ATP) [39] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My biosensor shows a low signal-to-noise ratio. What could be the cause and how can I improve it?

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal excitation wavelength or insufficient brightness of the reporting unit.

- Solution:

- Ensure your microscope's laser lines or LED sources align with the peak excitation spectrum of your fluorophore. Consult the literature for the specific biosensor's spectra [36].

- Consider switching to a brighter fluorescent protein variant. For example, the mStayGold fluorescent protein demonstrates ~3-fold higher brightness and significantly greater photostability compared to EGFP and mEmerald, which can drastically improve signal quality [42].

- For FRET sensors, verify that your filter sets are appropriate for the FRET pair and that you are correctly compensating for spectral bleed-through and cross-talk [37] [41].

FAQ 2: My intensiometric biosensor shows high cell-to-cell variability. Is this a biosensor artifact?

- Potential Cause: Fluorescence intensity is sensitive to local variations in biosensor expression concentration and path length, which is an inherent limitation of intensiometric designs [38].

- Solution:

- Where possible, use a ratiometric FRET biosensor, as the ratio measurement internally normalizes for the concentration of the biosensor [40].

- If you must use an intensiometric sensor, co-express a spectrally distinct, inert fluorescent protein (e.g., H2B-mApple [40]) as a reference marker to normalize for expression levels. Ensure the reference protein is localized to a compartment that does not interfere with the biosensor's measurement.

FAQ 3: How do I validate that my FRET biosensor is functioning correctly?

- Solution: Perform a positive control experiment to elicit a known biological response and confirm the expected change in the FRET ratio. Alternatively, the Acceptor Photobleaching (APB) method can be used for validation. This method involves measuring the donor fluorescence before and after selectively and irreversibly bleaching the acceptor fluorophore. An increase in donor fluorescence after bleaching confirms that FRET was occurring [37] [41]. The efficiency can be calculated as ( E = 1 - F{DA}/F{D} ), where ( F{DA} ) and ( F{D} ) are the donor fluorescence intensities before and after acceptor photobleaching, respectively [41].

FAQ 4: I need to combine a biosensor with an optogenetic actuator. What is the best strategy?

- Solution: Use red-shifted intensiometric biosensors. Their emission spectra do not overlap with the blue-light activation spectra used by many common optogenetic tools (e.g., CRY2/CIB, LOV domains). This spectral separation prevents cross-talk and allows for simultaneous manipulation and monitoring within the same cell [38]. The development of biosensors using dimerization-dependent red fluorescent proteins (R-FP) or far-red variants is particularly advantageous for these combinatorial approaches [36] [38].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Measuring ATP Dynamics in Neurons Using ATeam FRET Biosensors

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating metabolic deficits in neurodegenerative disease models [39].

- Gene Delivery: Transfert primary neurons with the plasmid encoding the ATeam1.03YEMK biosensor using an appropriate method (e.g., calcium phosphate, lipofection). ATeam integrates the ε-subunit of Bacillus subtilis F0F1-ATP synthase between the FRET pair mseCFP and mVenus [39].

- Imaging Setup: Place cultured neurons on a confocal or epifluorescence microscope equipped with environmental control (37°C, 5% CO₂). Use a 405 nm or 440 nm laser for CFP excitation.

- Data Acquisition:

- Collect emission signals simultaneously at ~480 nm (CFP/donor channel) and ~535 nm (YFP/acceptor FRET channel).

- Acquire time-lapse images at a suitable interval (e.g., every 30 seconds).

- Data Analysis:

- For each time point and region of interest (e.g., neuronal soma, synapses), calculate the FRET ratio as the background-subtracted intensity in the YFP channel divided by the background-subtracted intensity in the CFP channel.

- Express data as the change in ratio (ΔR/R₀) relative to the baseline ratio (R₀) before stimulation.

Protocol 2: Visualizing Small GTPase Activity with Red Intensiometric Biosensors

This protocol is for imaging Ras or Cdc42 activity in live cells or in vivo using the R-KRas or R-Cdc42 biosensors [38].

- Biosensor Expression: Express the bicistronic biosensor construct (e.g., B-RBDRaf1-2A-RA-KRas for R-KRas) in your target cells. The 2A peptide ensures co-expression of the effector and the GTPase at a fixed 1:1 ratio [38].

- Imaging Setup: Use a microscope system with a 561 nm laser for excitation of the red ddFP (RA) and a suitable emission filter (e.g., 600/50 nm).

- Stimulation and Acquisition:

- For in vitro experiments, add a stimulus like EGF (50 ng/mL) to activate Ras and acquire images at a high temporal resolution (e.g., 1-5 second intervals) to capture rapid kinetics [38].

- For in vivo imaging in the mouse brain, use a miniaturized microscope or a two-photon system to image the red fluorescence, which penetrates tissue more effectively.

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze the change in fluorescence intensity (F) over time in the red channel. Normalize the data as ΔF/F₀, where F₀ is the baseline fluorescence.

- Due to the intensiometric nature, carefully select cells with similar expression levels for comparison or use a co-expressed reference marker for normalization.

Essential Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core operational principles of FRET-based and intensiometric biosensors, which is fundamental to understanding their function and troubleshooting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| ATeam Biosensors [39] | FRET-based biosensors for intracellular ATP. | Monitoring energy dynamics in neurons and disease models. |

| MaLions Biosensors [39] | A family of intensiometric ATP biosensors (MaLionR, G, B). | Multiplexed imaging or targeting to different cellular compartments. |

| PercevalHR [39] | A FRET-based biosensor for the ATP/ADP ratio. | Assessing cellular energy status and metabolic changes. |

| ddFP-Based Small GTPase Sensors (G-/R-KRas, R-Cdc42) [38] | Intensiometric biosensors for Ras and Rho GTPase activity. | Visualizing spatiotemporal activity of signaling GTPases in vivo. |

| ECATS2 Biosensor [40] | A high-affinity, ratiometric FRET biosensor for extracellular ATP. | Studying purinergic signaling released under stress (e.g., hypoosmotic stress). |

| mStayGold Fluorescent Protein [42] | A very bright and photostable monomeric green fluorescent protein. | Tagging reporting units to enhance brightness and photostability. |

| H2B-mApple [40] | A red fluorescent nuclear localization marker. | Used as a reference fluorophore for normalizing expression levels. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our vgCam assay shows inconsistent ratio changes. What could be causing this? Inconsistent ratio changes often stem from three main issues:

- Incorrect Filter Sets: Ensure your microscope uses a precise violet excitation filter (~340 nm) for Sumire. Using a broader bandpass (e.g., 380-400 nm) can directly excite the T-Sapphire acceptor, leading to crosstalk and ratio compression [12].

- pH Instability: Although Sumire itself has a low pKa, the calcium-binding domain can be sensitive to pH fluctuations in the cytosol, especially during prolonged imaging or pharmacological treatments. Confirm your imaging buffers are well-buffered at physiological pH [12].

- Incomplete Chromophore Maturation: The hydrated chromophore of Sumire requires proper protein folding and maturation. Ensure cells are maintained at 37°C and allow sufficient time (24-48 hours post-transfection) for the sensor to mature fully before imaging [12].

Q2: Can vgCam be used simultaneously with a green calcium indicator like GCaMP? Yes, this is a key advantage of vgCam. The violet excitation (340 nm) and violet emission (414 nm) of the Sumire/T-Sapphire FRET pair are well-separated from the excitation (~480 nm) and emission (~510 nm) peaks of green indicators like GCaMP [12]. You must use a spectral unmixing approach or carefully selected filter sets to completely isolate the signals from both sensors and avoid bleed-through [43] [12].

Q3: We observe high background fluorescence in the violet channel. How can we reduce it? High background in the violet channel is frequently caused by cellular autofluorescence. To mitigate this:

- Use High-Quality Optics: Employ objectives and filters with high transmission efficiency in the violet range.

- Optimize Expression Levels: Use low plasmid concentrations or low MOI viruses to avoid sensor overexpression, which can increase background from cytosolic, unbound sensor [12] [44].

- Confirm Sensor Localization: The vgCam design removes 11 amino acids from the C-terminal of the donor FP to reduce unstructured regions that can contribute to background. Verify your construct sequence is correct [12].

Q4: What is the dynamic range of vgCam, and how does it compare to CFP-YFP-based cameleons? The original study characterizing vgCam reported a 2.4-fold change in the fluorescence intensity ratio (F510/F414) upon calcium binding [12]. This is comparable to many early-generation CFP-YFP cameleons but may be lower than some modern, high-performance green indicators. vgCam's primary value is not an extreme dynamic range but its spectral shift, which enables multiplexing.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio | 1. Sensor expression too low.2. Violet laser intensity too low or photobleaching.3. Chromophore immature. | 1. Increase transfection efficiency or virus titer.2. Optimize illumination; ensure Sumire's 340 nm excitation is used [12].3. Ensure cells are healthy and imaged >24h post-transfection. |

| No Response to Calcium Stimuli | 1. Sensor not functional.2. Calcium stimulus ineffective.3. Incorrect data processing. | 1. Validate sensor sequence and perform a positive control with ionomycin.2. Confirm stimulus efficacy (e.g., check membrane depolarization).3. Ensure you are measuring the ratio of T-Sapphire (510 nm) to Sumire (414 nm) emission [12]. |

| Signal Crosstalk in Multiplexing | 1. Bleed-through between channels.2. Direct excitation of acceptors. | 1. Perform control experiments to measure bleed-through and apply spectral unmixing [12].2. Use narrow-band filter sets and verify that the violet light does not excite green/yellow probes. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Key Protocol: Calibrating vgCam In Vitro

This protocol is essential for determining the absolute affinity (Kd) of your vgCam sensor before cellular experiments [45].

- Protein Purification: Express and purify recombinant vgCam protein using a standard His-tag or GST-tag system.

- Preparation of Calcium Buffers: Prepare a series of buffers with precisely defined free [Ca²⁺], ranging from zero (e.g., 10 mM EGTA) to saturating (e.g., 10 mM CaCl₂) levels. Use a calcium chelator like EGTA and calculation software to determine exact free [Ca²⁺] values [45].

- Spectrofluorometry Measurement: Dilute the purified vgCam protein into each calibration buffer.

- Excitation: Set the monochromator to 340 nm (excitation peak for Sumire's hydrated chromophore) [12].

- Emission Scan: Record the full emission spectrum from 400 nm to 550 nm for each buffer.

- Data Analysis: For each spectrum, calculate the ratio of fluorescence intensity at 510 nm (T-Sapphire acceptor) to 414 nm (Sumire donor). Plot this ratio against the free [Ca²⁺] and fit the data with the Hill equation to determine the Kd value for your specific vgCam preparation [45] [12].

Key Protocol: Co-imaging vgCam with a Green Indicator

This workflow allows for simultaneous monitoring of two distinct physiological parameters [12].

- Sensor Co-expression: Co-transfect cells with plasmids encoding vgCam and your chosen green biosensor (e.g., ATeam 1.03 for ATP [12]).

- Microscope Setup: Configure a microscope capable of rapid multi-channel acquisition.

- Channel 1 (vgCam): Use a 340 nm laser or LED for excitation. Collect emission using a beam splitter and two detectors: one at 414-460 nm (Sumire donor) and one at 510-550 nm (T-Sapphire acceptor).

- Channel 2 (Green Sensor): Use a 440 nm laser/LED (for CFP) or 480 nm (for GFP-based sensors) for excitation. Collect emission at 510-550 nm.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire images from all channels sequentially at each time point.

- Ratio Calculation and Analysis:

- For vgCam, calculate the ratio R = F(510 nm) / F(414 nm) for each pixel and time point.

- For the green sensor, calculate its specific ratio or use ΔF/F₀ for intensity-based probes.

- Analyze the kinetics and correlation between the two calculated traces.

The following diagram illustrates the core photophysical principle of the vgCam sensor and its experimental application in multiplexed imaging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for vgCam Development and Application

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sumire Fluorescent Protein | Violet-excited FRET donor; emits at 414 nm. | Key feature: Hydrated chromophore state for short-wavelength emission. Brightness is ~3.3x higher than Sirius in HeLa cells [12]. |