Fluorescent Proteins in Biomedicine: A 2025 Guide to Efficacy, Selection, and Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date comparison of fluorescent proteins (FPs) for biomedical research, catering to scientists and drug development professionals.

Fluorescent Proteins in Biomedicine: A 2025 Guide to Efficacy, Selection, and Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date comparison of fluorescent proteins (FPs) for biomedical research, catering to scientists and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of FP structure and discovery, explores advanced methodological applications in live-cell imaging and super-resolution microscopy, and offers practical troubleshooting for common experimental pitfalls. A central focus is the validation and comparative analysis of FP performance—including brightness, photostability, and oligomerization state—in physiologically relevant environments, moving beyond traditional in vitro data. The synthesis of these core intents delivers a decisive framework for selecting optimal FPs to enhance the accuracy and reliability of biomedical research.

The Fluorescent Protein Toolbox: From Jellyfish to Engineered Variants

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized biomedical research by enabling real-time visualization of cellular processes in living systems. This comparison guide traces the pivotal historical trajectory from the initial discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the engineering of coral-derived red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) and contemporary variants, providing objective performance data to inform researcher selection. We present quantitative comparisons of brightness, photostability, and spectral characteristics across the FP spectrum, alongside detailed experimental methodologies for key benchmarking assays. The expansion of the FP color palette, particularly into red-shifted regions, has addressed critical challenges in deep tissue imaging, multicolor experiments, and long-term live-cell observation, offering researchers an increasingly sophisticated toolkit for probing biological function.

The discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria marked a transformative moment in biological imaging [1]. First isolated in the early 1960s by Osamu Shimomura alongside the luminescent protein aequorin, GFP initially represented a scientific curiosity without immediate application [1] [2]. Its potential was unrealized until 1992 when Douglas Prasher cloned and sequenced the GFP gene, enabling its subsequent expression in heterologous systems by Martin Chalfie in 1994 [1]. This demonstration that GFP could autonomously form its fluorescent chromophore without jellyfish-specific cofactors established its utility as a universal genetic tag [1] [2].

The intrinsic properties of wild-type GFP, however, presented limitations for biomedical research, including dual-peaked excitation spectra, pH sensitivity, poor photostability, and inefficient folding at 37°C [1]. Protein engineering efforts addressed these shortcomings through systematic mutagenesis. The critical S65T mutation dramatically improved fluorescence intensity and photostability while shifting the major excitation peak to 488 nm, aligning it with standard fluorescence microscopy filter sets [1] [3]. The F64L mutation enhanced folding efficiency at 37°C, making GFP practical for mammalian cell studies [1]. These and subsequent modifications yielded enhanced GFP (EGFP), which became the benchmark against which subsequent FPs are measured [4] [2].

The cloning of GFP homologs from non-bioluminescent reef corals and sea anemones by Sergey Lukyanov's group dramatically expanded the spectral range of available FPs [5] [3]. The discovery of DsRed from Discosoma sea anemone introduced the first red-emitting FP, enabling new possibilities for multicolor imaging and deep-tissue observation [5]. However, wild-type DsRed presented drawbacks including slow maturation, obligate tetramerization, and formation of a green fluorescent intermediate, necessitating extensive protein engineering to produce monomeric, rapidly-maturing variants suitable for biological research [5].

The Expansion into Red: Coral Fluorescent Proteins

Structural Basis for Red Emission

The fundamental distinction between green and red fluorescent proteins lies in their chromophore structures. While both form from three consecutive amino acids within a polypeptide chain, RFPs undergo an additional oxidation step that extends the π-conjugation system through formation of an additional double bond in the chromophore (N-acylimine) [6] [5]. This extended conjugation system results in red-shifted excitation and emission spectra. However, the precise structural determinants enabling this additional oxidation remained elusive due to low sequence homology between GFP and RFP families [6].

Recent engineering breakthroughs have successfully converted coral-derived GFPs into RFPs through defined mutations. In one notable achievement, AzamiGreen (a coral GFP) was transformed into AzamiRed1.0 through 29 amino acid substitutions [6]. Structural analysis revealed that these mutations triggered drastic rearrangements in interaction networks around the fluorophore, creating a cavity suitable for oxygen entry necessary for the additional double bond formation [6]. This demonstrated that coordinated multisite mutations are required for green-to-red conversion, providing crucial insights into red fluorophore formation mechanisms.

The Monomerization Challenge

A significant hurdle in RFP development was the obligate tetramerization of natural coral proteins, which caused mislocalization and aggregation of fusion proteins [5]. Engineering monomeric RFPs required disrupting the extensive interaction surfaces between subunits. Through iterative mutagenesis, researchers introduced charged residues at interface contacts, first creating a dimeric intermediate and ultimately achieving monomeric RFP1 (mRFP1) [5]. This process involved 33 mutations, including 13 interface-disrupting mutations and 20 fluorescence-rescuing mutations, which unfortunately reduced intrinsic brightness but established a critical foundation for further development [5].

The "mFruit" series of monomeric RFPs emerged from subsequent engineering of mRFP1, yielding variants including mCherry, mStrawberry, and mPlum with emissions spanning orange to far-red [5] [3]. These monomeric RFPs enabled precise labeling of cellular structures without perturbing native function, dramatically expanding their utility for live-cell imaging [5].

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Fluorescent Proteins

Brightness and Spectral Characteristics

FP brightness is determined by the product of its molar extinction coefficient (ε, a measure of light absorption capacity) and fluorescence quantum yield (QY, the efficiency of photon conversion) [4]. Table 1 provides quantitative comparisons of historically significant and contemporary FPs across the visible spectrum.

Table 1: Spectral Properties and Brightness of Key Fluorescent Proteins

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Relative Brightness* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Fluorescent Proteins | ||||||

| EGFP | 484 | 507 | 56,000 | 0.60 | 100 | [4] [7] |

| Superfolder GFP | 485 | 510 | 83,300 | 0.65 | 160 | [7] |

| StayGold | 496 | 511 | 159,000 | 0.93 | 443 | [8] |

| Cyan Fluorescent Proteins | ||||||

| mTurquoise | 434 | 474 | 30,000 | 0.84 | 75 | [7] |

| mTFP1 (Teal) | 462 | 492 | 64,000 | 0.85 | 162 | [7] |

| Yellow Fluorescent Proteins | ||||||

| EYFP | 514 | 527 | 83,400 | 0.61 | 152 | [4] |

| Venus | 515 | 528 | 92,200 | 0.57 | 157 | [4] |

| Orange Fluorescent Proteins | ||||||

| mOrange | 548 | 562 | 71,000 | 0.69 | 146 | [7] |

| TagRFP | 555 | 584 | 100,000 | 0.48 | 142 | [7] |

| Red Fluorescent Proteins | ||||||

| DsRed | 558 | 583 | 75,000 | 0.79 | 176 | [7] |

| mCherry | 587 | 610 | 72,000 | 0.22 | 47 | [7] |

| AzamiRed1.0 | 571 | 606 | 34,100 | 0.65 | 66 | [6] |

| mKate2 | 588 | 633 | 62,500 | 0.40 | 74 | [4] |

*Relative brightness calculated as (ε × QY) / (ε(EGFP) × QY(EGFP)) × 100%

Brightness peaks in the middle visible spectrum with yellow and orange FPs, following general fluorophore properties [4]. Blue fluorophores have smaller extinction coefficients due to their smaller size, while red fluorophores suffer from lower quantum yields as larger conjugated systems have more vibrational degrees of freedom that dissipate energy non-radiatively [4]. The exceptional brightness of StayGold derives from both high extinction coefficient and near-unity quantum yield, representing a significant advance in FP performance [8].

Photostability and Environmental Sensitivity

Photostability determines the practical photon budget available for imaging experiments, particularly crucial for live-cell imaging and super-resolution techniques. Table 2 compares photostability and environmental sensitivity of representative FPs.

Table 2: Photostability and Stability Properties of Fluorescent Proteins

| Fluorescent Protein | Bleaching Half-time (s) | Maturation Half-time (min) | pKa | Oligomeric State | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | 501 | ~30 | 6.0 | Weak dimer | [4] [8] |

| StayGold | >10,000 | N/A | <4 | Dimer | [8] |

| mVenus | 58 | ~15 | 6.5 | Monomer | [4] |

| mOrange | 150 | N/A | 6.5 | Monomer | [5] |

| TagRFP | 132 | N/A | 5.2 | Monomer | [5] |

| mCherry | 348 | ~15 | 5.2 | Monomer | [4] |

| AzamiRed1.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Tetramer (monomeric variants available) | [6] |

Photobleaching rates show complex dependence on illumination intensity, with most FPs exhibiting "accelerated photobleaching" where bleaching rates increase supralinearly with intensity [4]. This has particular implications for confocal microscopy where instantaneous intensities are substantially higher than widefield microscopy. The extraordinary photostability of StayGold (>10,000 second half-time) represents over a 10-fold improvement over EGFP, enabling extended live-cell imaging and volumetric approaches [8].

Environmental sensitivity, particularly to pH, varies considerably among FPs. While most FPs show reduced fluorescence at acidic pH, some variants like StayGold and Sirius demonstrate exceptional pH resistance, functioning at pH values as low as 3-4 [3] [8]. This makes them particularly valuable for imaging in acidic environments such as secretory pathway compartments.

Experimental Protocols for FP Characterization

Photostability Assessment

Standardized protocols enable direct comparison of FP photostability across laboratories:

Protein Purification: Express FPs in E. coli and purify using affinity chromatography. Determine precise concentration using Bradford assay or spectrophotometry with extinction coefficients [8].

Sample Preparation: Embed purified FPs at identical concentrations (e.g., 1 μM) in polyacrylamide gel to mimic the intracellular environment and prevent diffusion during imaging [8].

Image Acquisition: Use widefield epifluorescence microscopy with continuous, unattenuated mercury or LED illumination (e.g., 5.6 W/cm² at 488 nm for green FPs). Maintain constant temperature [8].

Data Analysis: Normalize fluorescence decay curves to initial intensity. Calculate bleaching half-time (t₁/₂) as the time for initial emission rate to decay to 50%. Account for differences in extinction coefficient and quantum yield at the illumination wavelength when comparing different FPs [8].

For cellular photostability assessment, generate stable cell lines expressing cytosolic-targeted FPs. Acquire images at regular intervals under continuous illumination and analyze fluorescence decay in regions of interest, normalizing to initial intensity [8].

Quantum Yield Determination

The fluorescence quantum yield (QY) represents the efficiency of photon conversion:

Sample Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of purified FP in buffered solution at neutral pH. Measure absorbance at the excitation maximum, keeping values below 0.1 to minimize inner filter effects [4].

Standard Selection: Select appropriate reference standards with known QY values matching the spectral range of the test FP (e.g., quinine sulfate for cyan FPs, fluorescein for green FPs) [4].

Spectrofluorometric Measurement: Record emission spectra from 350-800 nm using spectrophotometer. Integrate the area under the fluorescence curve for both sample and standard [4].

Calculation: Apply the following equation: ΦX = ΦST × (GradX/GradST) × (ηX²/ηST²) Where Φ is quantum yield, Grad is the gradient from the plot of integrated fluorescence versus absorbance, and η is the refractive index of the solvent [4].

Oligomeric State Determination

Analytical ultracentrifugation provides the definitive method for determining FP oligomerization:

Sample Preparation: Dialyze purified FP against appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4) to establish equilibrium [8].

Centrifugation: Subject samples to velocity sedimentation (e.g., 50,000 rpm) while monitoring absorbance at appropriate wavelength [8].

Data Analysis: Fit sedimentation data to appropriate models to determine molecular weights and assess oligomeric states [8].

Pseudonative SDS-PAGE provides a complementary approach, where samples are electrophoresed without boiling. Monomeric FPs typically migrate at their predicted molecular weight (~27 kDa), while oligomeric forms show altered mobility [8].

Experimental Workflow and Research Reagents

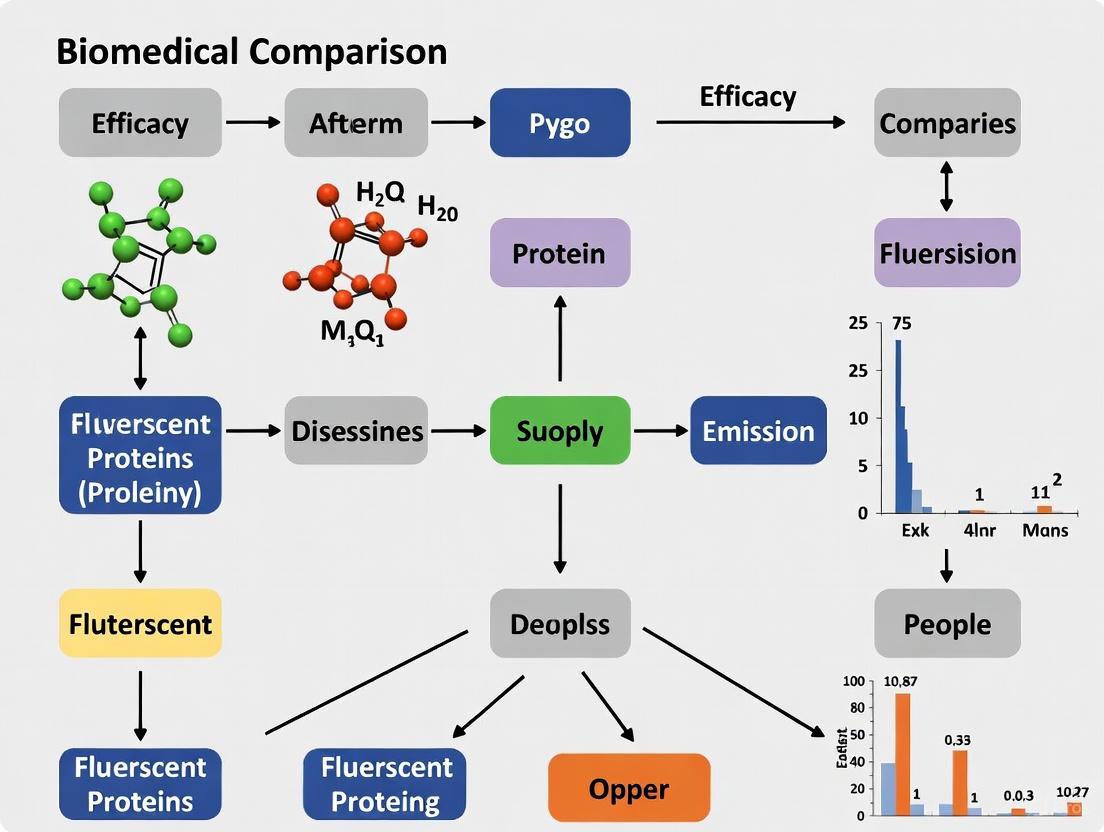

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for developing and characterizing novel fluorescent proteins:

Figure 1: Standard workflow for fluorescent protein development and characterization, from gene discovery to biological application.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescent Protein Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| FP Expression Vectors | Heterologous expression in model systems | pBAD, pET (bacterial); pcDNA3, pEGFP (mammalian) |

| Affinity Chromatography | Protein purification | His-tag/Ni-NTA; GST-tag/glutathione resin |

| Spectrophotometer | Extinction coefficient determination | UV-Vis with cuvette holder; measurement of absorbance spectra |

| Spectrofluorometer | Quantum yield determination | Measurement of excitation/emission spectra; photon counting |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Photostability assays | Embedding purified FPs for standardized bleaching measurements |

| Mammalian Cell Lines | Cellular characterization | HEK293, HeLa, COS-7 for localization and toxicity studies |

| Confocal Microscope | Cellular imaging and photostability | Laser scanning or spinning disk with environmental control |

Emerging Applications and Future Perspectives

Recent developments in FP technology continue to expand their utility in biomedical research. The discovery of StayGold from the jellyfish Cytaeis uchidae provides unprecedented photostability, enabling extended super-resolution imaging of organelles including the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria [8]. StayGold's tandem dimer version (tdStayGold) facilitates labeling of microtubules and neuronal structures while maintaining exceptional brightness and photostability [8].

Novel applications continue to emerge, including the recent demonstration that enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) can function as an optically addressable spin qubit at liquid-nitrogen temperatures [9]. This unexpected quantum property suggests potential applications in nanoscale field sensing and spin-based imaging modalities, potentially bridging fluorescence microscopy and quantum sensing [9].

The expansion of the FP color palette into the far-red and near-infrared regions continues, with variants such as mCardinal and mPlum enabling deeper tissue imaging with reduced autofluorescence [4] [3]. Ongoing engineering efforts focus on improving brightness while maintaining photostability, enhancing pH stability, and reducing residual dimerization tendencies in nominally monomeric FPs.

For researchers selecting FPs, considerations should include brightness, photostability, oligomeric state, maturation time, and environmental sensitivity, balanced against the specific experimental requirements including multicolor imaging, live-cell duration, and subcellular targeting [7]. The availability of comprehensive online databases such as FPbase provides updated spectral information and sequence data to inform these decisions [7].

The historical trajectory of fluorescent proteins—from fundamental curiosity to indispensable research tool—demonstrates how basic biological discovery can transform biomedical research. Ongoing protein engineering and the discovery of novel natural variants promise continued expansion of this versatile toolkit, enabling researchers to address increasingly complex biological questions with greater precision and clarity.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized biomedical research by enabling real-time visualization of cellular processes. The core of their function lies in a conserved structural framework: a protective β-barrel scaffold that encapsulates a self-catalyzed chromophore. This guide provides a comparative analysis of FP architecture and chromophore maturation, detailing how these elements dictate performance metrics critical for experimental outcomes. We present standardized experimental data and methodologies to objectively evaluate FP efficacy, empowering researchers to select optimal tools for imaging, biosensing, and live-cell tracking in drug development.

The discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria unveiled a unique structural motif that has become a cornerstone of modern biotechnology [10]. All GFP-like fluorescent proteins share a fundamental design: a β-barrel scaffold housing a central chromophore [11]. This cylindrical barrel is formed by 8 to 12 antiparallel β-strands, creating a rigid structure that shields the fluorophore from the external environment [10] [12]. The chromophore originates from an internal tripeptide sequence that undergoes autocatalytic cyclization, dehydration, and oxidation to form a conjugated π-electron system responsible for fluorescence [11] [10]. This structural blueprint is remarkably conserved across a diverse palette of FPs, from blue to far-red variants, despite significant sequence divergence [11].

Understanding the intimate relationship between the β-barrel and its chromophore is essential for selecting appropriate FPs for specific research applications. The barrel not only influences chromophore properties but also depends on the chromophore for its own stability, creating a complex interdependence that affects folding efficiency, maturation kinetics, and photophysical behavior [11] [13]. This guide deconstructs this structural relationship through comparative analysis of key FP variants, providing researchers with a framework for informed tool selection in biomedical investigations.

Structural Anatomy of Fluorescent Proteins

The β-Barrel Scaffold: Architecture and Conservation

The β-barrel of FPs typically consists of 11 antiparallel β-strands arranged in a cylindrical formation, often described as a "β-can" structure [10]. This scaffold measures approximately 4.2 nm in length and 2.4 nm in diameter, forming a rigid microenvironment that is crucial for chromophore function and fluorescence emission [10]. The interior surface of the barrel is predominantly hydrophobic, while the exterior exhibits hydrophilic characteristics that ensure solubility in aqueous cellular environments [11].

Strategic residues throughout the barrel play critical roles in structural integrity. Computational analyses of over 260 naturally occurring GFP-like proteins reveal that most conserved residues cluster in the turns between β-sheets at the top and bottom of the barrel, forming "lids" that may function as folding nuclei [13]. These conserved lid residues undergo less translational movement than other regions and potentially serve as hinges in FP dynamics [13]. Particularly conserved are glycine residues at positions 31, 33, and 35, whose structural roles remain incompletely understood despite their persistence across FP variants [11].

Table 1: Key Structural Elements of the Fluorescent Protein β-Barrel

| Structural Element | Composition | Function | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Strands | 8-12 antiparallel strands | Forms rigid cylindrical scaffold | High - number varies |

| Central α-Helix | Single helix running through barrel | Contains chromophore-forming tripeptide | High |

| N-terminal/C-terminal Loops | Variable sequences | Cap the ends of the barrel | Low |

| Lid Residues | Turns between β-sheets | Potential folding nuclei; structural stability | Very High |

| Internal Glycines | Positions 31, 33, 35 | Unknown structural role | Very High |

Chromophore Diversity and Spectral Characteristics

The fluorescent color of FPs is primarily determined by the chemical structure of the chromophore housed within the β-barrel. All FP chromophores originate from an internal tripeptide sequence (X65-Tyr66-Gly67) that undergoes autocatalytic modification, but variations in this core structure yield different spectral classes [11]:

- Green Fluorescent Chromophores: Feature a phenolic ring from Tyr66 and a five-membered heterocyclic structure with an oxidized double bond bridge creating a conjugated π-electron system [11].

- Red Fluorescent Chromophores (DsRed-like): Contain an additional desaturated Cα-N bond at Gln65 that extends π-conjugation, resulting in red-shifted absorption and emission [11].

- Kaede-like Chromophores: Composed of three aromatic rings where a GFP-like core is supplemented by an indole ring from His65 [11].

- Blue Fluorescent Chromophores: Possess a shorter π-conjugated system with an N-acylimine double bond and a phenolic ring nearly perpendicular to the heterocyclic structure [11].

The protein matrix surrounding the chromophore fine-tunes its fluorescent properties through electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and steric constraints [11]. Absolutely conserved catalytic residues Arg96 and Glu222 promote chromophore formation, with Arg96 acting as an electrostatic catalyst and Glu222 as a base catalyst [11].

Table 2: Chromophore Types and Their Spectral Properties

| Chromophore Type | Representative FPs | Core Structure | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | mTagBFP, mTagBFP2 | Five-membered heterocycle with N-acylimine | 399 | 456 |

| Cyan | ECFP, mCerulean | Trp66-containing imidazolone | 434 | 477 |

| Green | GFP, EGFP, mNeonGreen | 4-hydroxybenzylidene-imidazolinone | 488-505 | 507-515 |

| Yellow | EYFP, mVenus | π-conjugated phenolate-imidazolone | 514-525 | 527-540 |

| Red (DsRed-like) | DsRed, mCherry | Extended acylimine conjugation | 554-587 | 580-635 |

| Far-Red | Katushka2S, mCardinal | Further extended conjugation | 588-605 | 635-670 |

Chromophore Maturation: Biochemical Mechanism and Kinetics

The Maturation Pathway

Chromophore formation is a post-translational, autocatalytic process that requires only molecular oxygen as an external cofactor [10] [12]. The maturation mechanism proceeds through three well-defined steps:

- Cyclization: Correct protein folding brings the chromophore-forming tripeptide (X65-Tyr66-Gly67) into a strained conformation that enables nucleophilic attack by the amide nitrogen of Gly67 on the carbonyl carbon of residue 65. This forms an imidazolin-5-one heterocyclic ring [10] [12].

- Dehydration: The cyclized intermediate undergoes dehydration, though the precise sequence relative to oxidation remains debated [12].

- Oxidation: Molecular oxygen oxidizes the α-β carbon bond of Tyr66, extending electron conjugation to include the tyrosine phenyl ring and creating the mature fluorescent chromophore, 4-hydroxybenzylidene-imidazolinone (HBI) [10] [12].

The requirement for molecular oxygen as a fluorophore activation catalyst is remarkable considering that oxygen must be excluded from regular interactions with the mature fluorophore to avoid collisional quenching of fluorescence [10]. The generally low photobleaching rate of FPs suggests this design evolved as a compromise between efficient fluorophore formation and long-term stability [10].

Key Catalytic Residues and Structural Influences

Chromophore maturation depends critically on precisely positioned catalytic residues within the β-barrel. The highly conserved Arg96 and Glu222 residues facilitate the initial cyclization reaction, with Arg96 serving as an electrostatic catalyst and Glu222 acting as a base catalyst [11]. The absolutely conserved Gly67 is essential for forming the central α-helix with the required kinked conformation that positions the amide nitrogen for nucleophilic attack [11]. Substitution of Gly67 with any other residue impairs chromophore synthesis [11].

The β-barrel undergoes significant structural changes during chromophore maturation. Computational analyses comparing immature and mature FP structures reveal that the barrel contracts upon chromophore formation and becomes more rigid [13]. This compaction contributes to folding hysteresis, where unfolding and refolding pathways differ due to decreased flexibility of the chromophore compared to its immature analog [11] [13].

Figure 1: Chromophore Maturation Pathway. The fluorescent protein chromophore forms through a multi-step autocatalytic process requiring proper protein folding, cyclization, oxidation, and dehydration.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Fluorescent Proteins

Standardized Assessment Methodologies

Objective comparison of FP performance requires standardized experimental approaches that account for the complex intracellular environment. Recent advances have employed several innovative methodologies:

- Intracellular Nanocage Assembly: FP-tagged peptides self-assemble into stable 60-subunit dodecahedral nanoparticles, enabling quantitative brightness comparison on a molecule-by-molecule basis in live mammalian cells [14]. This approach normalizes for expression level and assembly efficiency, providing direct measurement of FP brightness in physiological conditions.

- Single-Copy Transgene Knock-ins: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated insertion of FP sequences into identical genomic loci enables direct comparison of brightness and photostability without confounding variables from differential expression or chromosomal position effects [15].

- Whole-Body Imaging in Model Organisms: Transfected cell implants in mice allow comparative assessment of signal intensity, penetration depth, and signal-to-noise ratio under biologically relevant conditions [16].

These methodologies reveal significant discrepancies between in vitro measurements and in vivo performance. For instance, while mNeonGreen (mNG) demonstrates superior brightness in purified protein assays, it underperforms relative to predictions in vivo, with yellow fluorescent protein mYPet exhibiting approximately four times greater brightness than mNG in C. elegans embryos [15].

Brightness and Photostability Comparisons

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Green Fluorescent Protein Performance

| Fluorescent Protein | Brightness Relative to EGFP | Photostability | Maturation Rate | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | 1.0 | Moderate | Moderate | Monomeric |

| mEmerald | 1.1 [14] | High | Moderate | Monomeric |

| mNeonGreen | 0.5 (in vivo) [15] | High | Fast | Monomeric |

| mYPet | 2.0 (in vivo) [15] | Moderate | Fast | Monomeric |

| mStayGold | 3.0 (nanocage assay) [14] | Very High | Fast | Monomeric |

| mBaoJin | 2.8 (nanocage assay) [14] | Very High | Fast | Monomeric |

Table 4: Quantitative Comparison of Red and Far-Red Fluorescent Protein Performance

| Fluorescent Protein | Brightness | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (in vivo) | Maturation Half-time | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mCherry | Moderate | Low | Fast | Monomeric |

| TagRFP-T | High | Moderate | Fast | Monomeric |

| mRuby2 | High | Moderate | Fast | Monomeric |

| mKate2 | Moderate | Low | Slow | Monomeric |

| Katushka2S | Very High [16] | High [16] | Very Fast [16] | Dimeric |

| mNeptune2.5 | Low [16] | Low [16] | Slow [16] | Monomeric |

| mCardinal | Moderate [16] | Moderate [16] | Slow [16] | Monomeric |

| iRFP720 | High [16] | High [16] | Fast [16] | Monomeric |

The recently developed StayGold variant and its monomeric derivatives represent significant advances in FP technology, demonstrating at least 3-fold greater brightness than EGFP in nanocage assays and exceptional photostability with a functional lifetime 8-10 times longer than EGFP or mEmerald [14]. For far-red imaging, Katushka2S emerges as the preferred GFP-like protein, exhibiting superior brightness and maturation rate compared to other far-red FPs, while bacterial phytochrome-based iRFP720 achieves comparable signal-to-noise ratio in whole-body imaging [16].

Experimental Protocols for FP Characterization

Nanocage Assembly for Quantitative FP Comparison

Principle: Self-assembling peptide nanocages (I3-01) form defined 60-subunit dodecahedrons, enabling precise comparison of FP brightness at the single-particle level in live cells [14].

Procedure:

- Construct Design: Fuse FP sequences to the N-terminus of I3-01 peptide via flexible linkers, ensuring exterior orientation in assembled nanocages.

- Cell Transfection: Express FP-I3-01 constructs in mammalian cells (e.g., human RPE cells) using appropriate transfection methods.

- Sample Preparation: 24-48 hours post-transfection, increase cytoplasmic viscosity by treating cells with 400 mOsm D-mannitol to slow nanocage diffusion and facilitate imaging.

- Image Acquisition: Image live cells using spinning disc confocal microscopy with standardized settings (500 ms exposure, appropriate laser power, 525/50 nm emission filter for green FPs).

- Particle Analysis: Identify sub-resolution nanocage particles in cell periphery. Fit 2D Gaussian distributions to individual particles and integrate fluorescence intensity within a radius of two standard deviations, subtracting local background.

- Data Analysis: Compare mean intensities across FP variants, normalizing to EGFP nanocages. Each nanocage represents 60 FP molecules, enabling per-molecule brightness calculation.

Applications: This method provides quantitative assessment of FP performance in physiological intracellular environments, free from artifacts of variable expression levels or incomplete peptide cleavage [14].

Whole-Body Imaging for In Vivo FP Assessment

Principle: Transiently transfected cell implants in mice enable comparison of FP performance in deep tissues, accounting for tissue absorption, scattering, and autofluorescence [16].

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Transfect HEK293FT cells with FP expression plasmids containing IRES-driven luciferase for signal normalization.

- Animal Implantation: Inject transfected cells intramuscularly into nude mice at approximately 5 mm depth.

- Multispectral Imaging: Image anesthetized mice using IVIS Lumina II or similar system with multiple excitation wavelengths (500-640 nm) and emission filters (DsRed: 575-650 nm; Cy5.5: 695-770 nm).

- Signal Quantification: Acquire luminescence images for normalization, then quantify fluorescence signals and calculate signal-to-noise ratios for each FP across spectral channels.

- Spectral Unmixing: Utilize differential signal patterns across channels to distinguish multiple FPs in the same animal.

Applications: This protocol identifies optimal FP combinations for multiplexed in vivo imaging and provides critical data on tissue penetration and contrast for whole-body imaging applications [16].

Figure 2: Fluorescent Protein Assessment Workflow. Comprehensive FP evaluation employs multiple methodological approaches to quantify key performance metrics under biologically relevant conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Reagents for Fluorescent Protein Research and Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| FP Expression Vectors | Encoding FP sequences with appropriate promoters | Mammalian expression, transfection | Choose cell-type specific promoters; consider 2A peptide systems for co-expression |

| Genome Editing Tools | Precise FP integration into endogenous loci | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, homologous recombination templates | Enables single-copy expression at native loci; reduces expression variability |

| I3-01 Nanocage System | Self-assembling peptide for quantitative FP comparison | Standardized brightness assessment in live cells | Provides defined oligomerization state; enables per-molecule quantification |

| Spectral Unmixing Software | Separating overlapping FP signals | Multicolor imaging, multiplexed detection | Requires reference spectra; effectiveness depends on spectral separation |

| IVIS Imaging Systems | Whole-body fluorescence imaging | In vivo animal studies, tumor progression tracking | Multiple filter sets needed for comprehensive spectral characterization |

| Spinning Disc Confocal Microscopy | High-resolution live-cell imaging | Subcellular localization, dynamic processes | Reduced phototoxicity compared to laser scanning confocals |

| Hyperosmotic Reagents (D-mannitol) | Increasing cytoplasmic viscosity | Slowing intracellular diffusion for particle tracking | Enables capture of fast-moving structures; concentration-dependent effects |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Novel Engineering Approaches and De Novo Design

Recent innovations have expanded FP capabilities beyond natural variants. De novo design of β-barrel proteins that bind and activate fluorogenic dyes represents a groundbreaking approach to creating synthetic FPs [17]. These designed proteins demonstrate that the β-barrel scaffold can be engineered from first principles rather than derived from natural templates, opening possibilities for custom FPs with tailored properties.

Additionally, the discovery that FPs can function as optically addressable spin qubits introduces entirely new applications in quantum biology and nanoscale sensing [9]. Enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) has been shown to possess a metastable triplet state that can be manipulated with microwave control, demonstrating coherence times of up to 16 μs [9]. This finding transforms FPs from mere fluorescence markers to potential quantum sensors capable of detecting nanoscale magnetic fields, temperature, and electric fields within cellular environments.

Optimization for Advanced Imaging Modalities

The continuing evolution of FP technology addresses persistent challenges in biomedical imaging:

- Reduced Aggregation: Engineering of truly monomeric FPs enables more accurate protein fusion studies without artifactual clustering.

- Enhanced Photostability: Variants like StayGold provide dramatically improved resistance to photobleaching, enabling extended time-lapse imaging [14].

- Maturation Efficiency: Improved folding and maturation kinetics allow faster visualization after protein synthesis, critical for tracking dynamic cellular processes.

- Spectroscopic Diversity: The development of spectrally distinct FPs with large Stokes shifts facilitates multiplexed imaging and FRET-based biosensors.

As FP engineering progresses, the integration of computational design with high-throughput screening will likely yield next-generation probes with optimized characteristics for specialized applications in drug discovery and diagnostic development.

The structural blueprint of fluorescent proteins—a protective β-barrel scaffold housing a autocatalytically-formed chromophore—represents a remarkable natural architecture that has been optimized through both evolution and protein engineering. The intimate relationship between these structural elements dictates FP performance in research applications, with chromophore chemistry determining spectral properties and the β-barrel governing folding efficiency, stability, and environmental resilience.

Comparative analysis reveals that while no single FP excels in all characteristics, optimal variants exist for specific research needs: StayGold derivatives for extreme photostability, Katushka2S for far-red in vivo imaging, and mYPet for bright yellow fluorescence in cellular contexts. The continued diversification of the FP toolkit, coupled with standardized assessment methodologies, empowers researchers to select optimal probes for their experimental systems, driving advances in our understanding of biological mechanisms and accelerating the development of novel therapeutics.

As FP technology expands into emerging fields including quantum sensing and de novo protein design, these versatile molecular tools will undoubtedly continue to illuminate fundamental biological processes and contribute to biomedical innovation.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have fundamentally transformed biomedical research by enabling real-time observation of dynamic biological processes in live cells and organisms [14]. From their origins in the Aequorea victoria jellyfish, the FP toolkit has expanded to encompass a full spectrum of colors, each with unique photophysical properties tailored for specific applications in live-cell imaging, flow cytometry, and biosensor development [18] [19]. The color classification of FPs—spanning from blue to near-infrared—provides researchers with a versatile palette for multiplexed imaging, where multiple cellular targets can be visualized simultaneously [20]. However, this diversity presents a significant challenge: selecting optimal FPs requires careful consideration of brightness, photostability, oligomeric state, and performance in specific physiological environments [14]. This guide provides a systematic, data-driven comparison of FPs across the color spectrum, empowering researchers to make informed decisions based on the latest experimental evidence and performance metrics relevant to modern biomedical research.

FP Classification and Performance Metrics

The Biochemical Basis of Fluorescence Color

The color of an FP is determined by the electronic structure of its chromophore—a formed amino acid sequence within the protein's β-barrel structure that absorbs and emits light at specific wavelengths [21]. The chromophore's chemical environment, including adjacent amino acids and structural constraints, fine-tunes the excitation and emission spectra, creating the diversity of colors available to researchers. Blue and cyan FPs typically feature shorter conjugation systems in their chromophores, while red and near-infrared variants exhibit more extended electron delocalization, resulting in longer wavelength emission [18]. This structural basis directly impacts key performance metrics including brightness (a product of extinction coefficient and quantum yield), photostability (resistance to photobleaching), maturation efficiency (rate of chromophore formation), and oligomeric state (monomeric vs. dimeric/tetrameric tendencies) [14] [19]. Monomeric FPs are generally preferred for protein fusion constructs as they minimize interference with normal protein function and localization [19].

Quantitative Comparison of FPs Across the Spectrum

The following tables provide standardized performance data for commonly used FPs across the color spectrum, compiled from recent experimental characterizations.

Table 1: Blue to Yellow-Green Fluorescent Proteins

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Brightness Relative to EGFP | Photostability | Oligomeric State | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTagBFP2 | 399 | 454 | ~80% | Moderate | Monomeric | Flow cytometry, FRET donor |

| mCerulean3 | 433 | 475 | ~85% | Moderate | Monomeric | FRET, multiplexed imaging |

| Sapphire | 399 | 511 | ~50% | Low | Monomeric | Specialized applications |

| EGFP | 488 | 507 | 100% (reference) | Moderate | Monomeric | General tagging, reference |

| mNeonGreen | 506 | 517 | ~180% | High | Monomeric | Super-resolution, live-cell |

| EYFP | 513 | 527 | ~115% | Moderate | Monomeric | Historical use, FRET |

| Venus | 515 | 528 | ~125% | Moderate | Monomeric | FRET, biosensors |

| mStayGold | ~499 | ~511 | ~300% | Extremely High | Monomeric | Long-term live-cell imaging |

Table 2: Orange to Near-Infrared Fluorescent Proteins

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Brightness Relative to mCherry | Photostability | Oligomeric State | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LssmOrange | 437 | 572 | ~90% | Moderate | Monomeric | Flow cytometry |

| mOrange2 | 549 | 565 | ~110% | Moderate | Monomeric | General tagging |

| mApple | 568 | 592 | ~120% | Moderate | Monomeric | General tagging |

| tdTomato | 554 | 581 | ~240% | High | Tandem dimer | Bright labeling |

| mCherry | 587 | 610 | 100% (reference) | Moderate | Monomeric | General tagging, reference |

| TagRFP657 | 611 | 657 | ~95% | Moderate | Monomeric | Flow cytometry, deep tissue |

| mScarlet | 569 | 594 | ~130% | High | Monomeric | Protein fusions |

| mIFP | 683 | 704 | ~60% | Low-Moderate | Monomeric | Near-infrared imaging |

Recent quantitative comparisons using standardized intracellular nanocage assemblies reveal that mStayGold demonstrates exceptional performance in the green spectrum, with approximately 3-fold higher brightness compared to EGFP and a functional lifetime at least 8-10 times longer than EGFP or mEmerald [14]. In the red spectrum, performance differences between recent variants (mScarlet, mRuby) and the established mCherry are less pronounced on typical spinning disc confocal microscope systems [14].

Experimental Protocols for FP Validation

Standardized Intracellular Brightness Assessment

Accurately comparing FP brightness in live cells presents significant challenges due to variations in expression levels and maturation efficiency. Recent research has developed nanocage-based standardization methods that enable molecule-by-molecule comparison in physiological intracellular environments [14].

Protocol: Nanocage-Based FP Brightness Assay

- Construct Design: Fuse FP genes to the N-terminus of I3-01 peptides, which self-assemble into stable 60-subunit dodecahedral structures [14].

- Cell Transfection: Express FP-tagged I3-01 constructs in mammalian cells (e.g., human retinal pigmental epithelial cells) using appropriate transfection methods.

- Sample Preparation: Increase cytoplasmic viscosity by treating cells with 400 mOsm D-mannitol to slow nanocage diffusion and facilitate imaging [14].

- Image Acquisition: Image cells using spinning disc confocal microscopy with standardized settings (e.g., 488 nm excitation, 500 ms exposure, 525/50 nm emission filter for green FPs) [14].

- Quantitative Analysis: Fit 2D Gaussian distributions to individual sub-resolution nanocage particles and integrate fluorescence intensity within a circle of two standard deviations, subtracting local background [14].

This method circumvents issues with traditional 2A peptide approaches, where incomplete cleavage and differential maturation can skew results, by providing a system with defined stoichiometry where each nanocage contains exactly 60 FP molecules [14].

Photostability and Lifetime Measurements

Photostability is a critical parameter for long-term live-cell imaging, and fluorescence lifetime provides additional information about the fluorophore's molecular environment.

Protocol: Photobleaching and FLIM Analysis

- Sample Preparation: Express FP-tagged constructs in cells or purify FPs for in vitro analysis.

- Photobleaching Setup: Expose samples to continuous illumination at defined power densities while recording fluorescence intensity over time.

- Data Analysis: Fit fluorescence decay curves to exponential functions to determine photobleaching half-lives [14].

- FLIM Acquisition: For lifetime measurements, use time-domain or frequency-domain fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) systems [21].

- Lifetime Calculation: Analyze photon arrival times to determine fluorescence lifetimes, which represent the average time a fluorophore remains in its excited state before emitting a photon [21] [20].

Recent developments in time-resolved FPs (tr-FPs) have expanded opportunities for multiplexed imaging based on fluorescence lifetime, enabling simultaneous visualization of up to 9 different targeting proteins in live cells [20].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for standardized FP performance assessment using nanocage technology.

Advanced Applications and Biosensor Design

FRET-Based Biosensors

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) represents a powerful application of FPs for monitoring molecular interactions and conformational changes. FRET occurs when an excited donor FP nonradiatively transfers energy to an acceptor FP through dipole-dipole coupling, with efficiency inversely proportional to the sixth power of the distance between them (effective range: 1-10 nm) [22] [23].

Key Considerations for FRET Pair Selection:

- Spectral Overlap: Significant overlap (>30%) between donor emission and acceptor excitation spectra is required [22].

- Orientation Factor: The relative orientation of donor and acceptor transition dipoles (κ²) impacts energy transfer efficiency [23].

- Brightness and Quantum Yield: High-quantum-yield donors and high-extinction-coefficient acceptors improve FRET sensitivity [22].

Commonly used FRET pairs include mCerulean3/mVenus (cyan/yellow), EGFP/mCherry (green/red), and specialized pairs optimized for specific applications such as calcium sensing or kinase activity monitoring [22].

Figure 2: FRET mechanism demonstrating distance-dependent energy transfer between FPs.

Multiplexed Imaging and Super-Resolution Applications

The expanding color palette of FPs enables increasingly sophisticated multiplexed imaging approaches. Recent advances include:

- Time-Resolved FPs (tr-FPs): Engineered variants covering the visible spectrum (383-627 nm) with a wide range of fluorescence lifetimes (1-5 ns) enable multiplexing based on both spectral and lifetime differences [20].

- Super-Resolution FLIM: Integration of tr-FPs with super-resolution techniques like STED-FLIM allows visualization of multiple subcellular organelles and cytoskeletal proteins in live cells [20].

- Flow Cytometry Panels: Carefully selected FP combinations enable multicolor flow cytometry with minimal spectral overlap. Optimal combinations include mTagBFP2 (blue), GFP/Venus (green), and mIFP/TagRFP657 (red/far-red) [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FP Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| FP-tagged I3-01 nanocages | Standardized assemblies for quantitative FP comparison in live cells | Brightness and photostability assessment [14] |

| 2A peptide vectors | Co-expression of multiple FPs from a single transcript | Relative brightness comparisons, controls [14] |

| Hypertonic treatment solutions (D-mannitol) | Reduce intracellular diffusion for improved particle imaging | Nanocage imaging and tracking [14] |

| FLIM calibration standards | Reference materials for fluorescence lifetime validation | Microenvironment sensing, FRET efficiency calculations [21] |

| HaloTag/SNAP-tag systems | Alternative labeling systems for small-molecule dyes | Multiplexing with FPs, expanded color range [20] |

| Spectral unmixing algorithms | Computational separation of overlapping FP signals | Multiplexed imaging with spectrally similar FPs [20] |

| Photoswitching buffers | Control FP photophysics in super-resolution imaging | PALM/STORM imaging techniques |

The expanding color palette of FPs, from blue to near-infrared, provides researchers with an unprecedented toolkit for probing cellular function. While recent developments like mStayGold offer remarkable improvements in photostability and brightness, performance in the red and near-infrared regions remains an area for continued optimization [14]. The ideal FP combination depends heavily on specific experimental requirements, including imaging modality, required temporal resolution, and multiplexing needs.

Future directions in FP development include:

- Further expansion into the near-infrared for improved tissue penetration and reduced autofluorescence [18].

- Engineering of FPs with tailored fluorescence lifetimes for increased multiplexing capacity [20].

- Development of "smart" FPs that respond to specific cellular conditions or enzymatic activities.

- Standardization of benchmarking methods to enable more accurate comparison of newly developed FPs [14].

As these tools continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly unlock new possibilities for visualizing and understanding the complex molecular interactions that underlie health and disease.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the visualization and tracking of cellular components and processes in living systems [24]. The efficacy of these genetic tools in applications ranging from super-resolution microscopy to drug screening hinges on a fundamental understanding of their key photophysical properties. Among these, brightness, quantum yield, and extinction coefficient are paramount, collectively determining the signal intensity that a fluorescent protein can produce in an experiment [25]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these properties across a spectrum of FPs, underpinned by experimental data, to aid researchers in making informed decisions for their specific biomedical applications.

Defining the Core Photophysical Properties

The performance of a fluorescent protein is quantitatively described by three intrinsic properties.

Extinction Coefficient (ϵ)

The extinction coefficient is a measure of how efficiently a fluorophore absorbs light at a specific wavelength [25]. It is a direct measure of the ability of a molecule to absorb light. A higher extinction coefficient means the FP has a greater probability of absorbing photons, leading to more molecules being excited. This parameter is analogous to the cross-sectional area for photon capture and is typically reported in units of M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [4].

Quantum Yield (Φ)

The quantum yield is the ratio of the number of photons emitted to the number of photons absorbed [25]. It defines the efficiency with which the absorbed light is converted into emitted fluorescence. A quantum yield of 1.0 signifies that every absorbed photon results in an emitted photon, while a yield of 0 means no fluorescence is produced. Quantum yields of FPs commonly range from 0.05 to near 1.0 [25].

Brightness

The brightness of a fluorophore is the product of its extinction coefficient and its quantum yield (Brightness = ϵ × Φ) [25]. This composite metric defines the total fluorescence output per molecule and is often reported relative to a standard, such as Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) [4]. It is crucial to distinguish this theoretical or intrinsic brightness from practical brightness, which also depends on the folding efficiency and maturation of the FP within the cellular environment, the microscope's light source and detectors, and the background autofluorescence of the sample [26].

The Photophysical Workflow

The relationship between these properties and the process of fluorescence can be summarized in the following workflow, from photon absorption to the final detected signal.

Quantitative Comparison of Fluorescent Proteins

The following tables summarize the key photophysical properties of popular and high-performing FPs across the visible spectrum. Data is primarily derived from large-scale quantitative assessments [4]. Brightness is normalized to EGFP.

Table 1: Green, Yellow, and Orange Fluorescent Proteins

| Protein (Acronym) | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Relative Brightness (% of EGFP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | 484 | 507 | 56,000 | 0.60 | 100 (Reference) |

| Emerald | 487 | 509 | 57,500 | 0.68 | 116 |

| mVenus | 515 | 528 | 92,200 | 0.57 | 157 |

| mKO2 | 551 | 565 | 63,800 | 0.62 | 118 |

| mOrange | 548 | 562 | 58,000 | 0.45 | 78 |

Table 2: Blue, Cyan, and Red Fluorescent Proteins

| Protein (Acronym) | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Relative Brightness (% of EGFP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTagBFP | 399 | 456 | 52,000 | 0.63 | 98 |

| mCerulean | 433 | 475 | 43,000 | 0.62 | 79 |

| mTurquoise | 434 | 474 | 30,000 | 0.84 | 74 |

| mCherry | 587 | 610 | 72,000 | 0.22 | 47 |

| mKate2 | 588 | 633 | 62,500 | 0.40 | 74 |

| mCardinal | 604 | 659 | 87,000 | 0.19 | 49 |

| mPlum | 590 | 649 | 41,000 | 0.10 | 12 |

Experimental Protocols for Property Determination

Protocol for Measuring Extinction Coefficient and Quantum Yield (Relative Method)

This conventional method requires a purified FP sample and a reference standard with a known quantum yield [4].

- Sample Preparation: Purify the fluorescent protein in a suitable buffer (e.g., Tris buffer at pH 7.5). Precisely determine the protein concentration using a method like absorbance at 280 nm (accounting for the fluorophore's own absorbance) or a colorimetric assay [4].

- Absorbance Measurement: Record the absorbance spectrum of the purified FP solution. The extinction coefficient (ϵ) is calculated from the absorbance at the peak maximum (A) using the Beer-Lambert law: A = ϵ c l, where c is the molar concentration and l is the path length of the cuvette.

- Fluorescence Emission Measurement: Record the fluorescence emission spectrum of the sample, exciting at the absorption maximum. Ensure the absorbance is low (<0.1) to avoid inner-filter effects.

- Quantum Yield Calculation: The quantum yield (ΦX) of the unknown FP is calculated by comparing its emissive properties to a reference standard (ΦST) using the formula: ΦX = ΦST × (AST/AX) × (IX/IST) × (ηX²/ηST²) where A is absorbance at the excitation wavelength, I is the integrated area under the fluorescence emission spectrum, and η is the refractive index of the solvent [27].

Advanced Protocol: Absolute Quantum Yield Measurement Using a Plasmonic Nanocavity

This calibration-free method overcomes the limitation of conventional techniques by being insensitive to non-fluorescent absorbing species (e.g., immature proteins) [27].

- Principle: The method modulates the radiative decay rate (kr) of the fluorophore by placing it within a subwavelength plasmonic nanocavity formed by two silver mirrors. The modulation depends on the cavity size and the fluorophore's intrinsic quantum yield [27].

- Setup: A confocal microscope is coupled with the nanocavity. The bottom mirror is a vapor-deposited silver layer on a cover glass, and the top mirror is a silver-coated plano-convex lens. The cavity size is tuned by laterally moving the laser focus using a piezo stage [27].

- Measurement:

- A sub-micromolar solution of the FP in buffer is placed in the nanocavity.

- The fluorescence lifetime (τ) of the FP is measured as a function of the cavity's transmission wavelength (which correlates with mirror distance).

- The lifetime is shortest in the λ/2 region of the cavity, where radiative rate enhancement is maximal [27].

- Data Analysis: The measured lifetime versus cavity size data is fitted with a semi-classical quantum-optical model. The fit directly yields the absolute quantum yield and the free-space fluorescence lifetime without requiring a reference standard or knowledge of the concentration of fluorescent molecules [27].

Protocol for Assessing Practical Brightness in Live Cells

This assay determines the practical brightness of FPs under realistic biological conditions, accounting for maturation efficiency and cellular environment [26].

- Plasmid Design: Construct a vector where the FP of interest and a reference FP (e.g., mTurquoise2) are co-expressed from the same open-reading frame, separated by a self-cleaving 2A peptide. This ensures a 1:1 stoichiometric expression of both proteins, correcting for cell-to-cell variation in transfection efficiency [26].

- Cell Transfection and Imaging: Transfert mammalian cells with the constructed plasmid and image them using a microscope setup with appropriate filter sets for both FPs.

- Data Analysis: For each cell, measure the fluorescence intensity of both the FP of interest and the reference FP. Plot the intensity of the test FP against the reference FP. The slope of the resulting linear correlation is a direct measure of its practical brightness relative to the reference FP [26].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents required for the experimental characterization of fluorescent proteins.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Fluorescent Protein Characterization

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Purified FPs | Essential for in vitro determination of extinction coefficient and quantum yield. | Proteins should be highly purified and in a defined buffer [4]. |

| Reference Fluorophores | Act as quantum yield standards for relative measurements. | Examples include dyes with known, stable QYs (e.g., Fluorescein, QY=0.92) [28]. |

| Expression Vectors | For expressing FPs in live cells to assess practical brightness and performance. | Plasmids with 2A peptide systems for co-expression are particularly useful [26]. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Used as an inert matrix to immobilize purified FPs for photostability measurements. | Prevents diffusion during prolonged illumination [4] [29]. |

| Plasmonic Nanocavity | Enables calibration-free, absolute quantum yield measurement. | Custom-built setup involving silver mirrors and a precision positioning stage [27]. |

| Tris Buffer | A common physiological buffer for maintaining stable pH during FP measurements. | Typically used at pH 7.5 [27]. |

| Mammalian Cell Lines | Provide the biological context for testing practical brightness and fusion protein behavior. | Lines like HEK293 or HeLa are commonly used [24] [26]. |

Advanced FP Applications in Live-Cell Imaging and Biomedical Research

The use of fluorescent proteins (FPs) has revolutionized biomedical research, enabling scientists to visualize and study cellular processes in real-time within living systems. A critical step in this process is the creation of a functional fusion protein, where a fluorescent protein is genetically linked to a protein of interest (POI). The strategic decisions involved in how this fusion is constructed—specifically, whether the tag is placed at the N-terminus or C-terminus, and the design of the peptide linker connecting them—are fundamental to the success of the experiment. These choices directly influence the folding, stability, localization, and ultimate biological activity of the resulting chimeric protein. This guide provides a comparative analysis of terminal fusion strategies and linker design, equipping researchers with the knowledge to make optimal choices for their specific experimental needs in drug development and basic research.

Terminal Fusion Strategies: A Comparative Analysis

The placement of the fluorescent protein tag, at either the N- or C-terminus of your target protein, is one of the most consequential decisions in construct design. The optimal choice is primarily dictated by the structure and function of the native protein.

Strategic Considerations for Tag Placement

- N-terminal Fusions: This strategy involves fusing the fluorescent protein to the start of the protein of interest. It is generally preferred when the C-terminus of the POI is critical for its function, for example, if it contains a localization signal (such as a peroxisomal targeting signal -SKL- or a endoplasmic reticulum retention signal -KDEL-), a lipid modification site (e.g., for prenylation or palmitoylation), or is involved in catalytic activity or protein-protein interactions [30].

- C-terminal Fusions: This approach places the fluorescent protein at the end of the POI. It is the right choice when the N-terminus is functionally important. This is often the case for proteins possessing signal peptides for secretion or organellar targeting, mitochondrial import signals, or other N-terminal domains essential for function or partnership [30].

A classic example highlighting the importance of this choice is the enzyme APT1. When fused as APT1-mVenus (C-terminal tag), the protein localizes correctly to the Golgi apparatus. In contrast, the mVenus-APT1 (N-terminal tag) fusion is mislocalized because the N-terminal tag occludes a lipidation motif essential for its proper cellular targeting [30].

Advantages and Disadvantages at a Glance

Table 1: Comparison of N-terminal and C-terminal Fusion Strategies

| Feature | N-terminal Fusion | C-terminal Fusion |

|---|---|---|

| Best For | POIs with critical C-terminal functional domains | POIs with critical N-terminal functional domains (e.g., signal peptides) |

| Risk of Interference | May disrupt N-terminal signals, folding, or initial synthesis | May mask C-terminal localization motifs, interaction sites, or active sites |

| Construct Design | FP-Linker-POI | POI-Linker-FP |

| Functional Validation | Comparison with C-terminal fusion and native protein localization is critical | Comparison with N-terminal fusion and native protein localization is critical |

The Role of Linkers in Fusion Protein Design

A linker, or spacer, is a short amino acid sequence that sits between the fluorescent protein and the POI. While a direct fusion is sometimes feasible, the use of a designed linker is a standard practice to prevent steric hindrance and ensure that both domains fold independently and correctly [31] [32].

Types of Peptide Linkers

- Flexible Linkers: These are the most commonly used linkers. Composed of small, polar amino acids like Glycine (G) and Serine (S), they form unstructured, flexible peptides that act like a tether, allowing the two protein domains a degree of spatial freedom. The canonical example is the (GGGGS)n repeat, where n is typically 1 to 5 repeats [31] [32]. These are ideal for situations where the two domains do not need to interact directly.

- Rigid Linkers: These linkers are designed to keep the fused domains separated by a fixed distance. They are often formed from alpha-helix-forming sequences of amino acids such as (EAAAK)n. The helical structure provides rigidity, preventing the linker from coiling and ensuring the two protein domains remain apart [32]. This is useful for preventing unwanted interactions or in Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) sensors where distance is a critical parameter.

- In Vivo Cleavable Linkers: These specialized linkers contain a recognition sequence for a specific protease (e.g., TEV protease, Furin). They allow for the controlled separation of the fluorescent protein tag from the POI after purification or inside the cell, which is vital for certain functional assays or therapeutic applications [32].

Table 2: Common Linker Types and Their Applications

| Linker Type | Example Sequence | Primary Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible | (GGGGS)n [32] | General-purpose fusion; independent domain function | Unstructured, provides high degrees of freedom |

| Rigid | (EAAAK)n [31] | FRET biosensors; fixed domain separation | Alpha-helical structure, prevents domain interaction |

| Cleavable | ENLYFQG (TEV site) [32] | Tag removal post-purification | Specific protease recognition site |

Quantitative Performance of Fluorescent Proteins

The choice of the fluorescent protein itself is equally critical. Recent advances have led to FPs with vastly improved brightness and photostability, which are essential for prolonged live-cell imaging.

Standardized Intracellular Performance Data

A 2025 study provided a standardized, quantitative comparison of various FPs by expressing them as fusions to a self-assembling protein nanocage inside live mammalian cells. This innovative system allows for a molecule-by-molecule comparison in a physiological environment. The study combined brightness and photobleaching measurements into a single functional performance metric [33].

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Fluorescent Protein Performance in Live Mammalian Cells [33]

| Fluorescent Protein | Color | Relative Functional Lifetime | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| mStayGold | Green | > 8-10x EGFP/mEmerald | Exceptional photostability; confirmed monomeric |

| mEmerald | Green | Baseline (1x) | Bright, earlier-generation green FP |

| EGFP | Green | Baseline (1x) | Widely used standard green FP |

| mScarlet/mRuby3 | Red | No substantial improvement over mCherry | Bright, but limited photostability gain |

| mCherry | Red | Baseline (1x) | Common standard red FP |

The data clearly shows that mStayGold stands out as a superior green fluorescent protein, with a functional lifetime at least 8-10 times longer than EGFP or mEmerald. This makes it an excellent choice for long-term time-lapse experiments where photobleaching is a major concern. In the red spectrum, the performance of newer proteins like mScarlet and mRuby3 was found to be not substantially better than mCherry on a standard spinning disc confocal microscope, highlighting the importance of benchmarking FPs for specific experimental setups [33].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Validating Fusion Protein Localization

A critical step after generating a fusion construct is to verify that it recapitulates the native localization and behavior of the untagged protein.

- Construct Design: Generate multiple constructs (e.g., N-terminal FP-POI, C-terminal POI-FP) with short, flexible linkers (e.g., PVAT or GGGGS) [30].

- Transfection: Introduce the constructs into an appropriate cell line.

- Imaging & Comparison: Image the live or fixed cells using fluorescence microscopy. The localization pattern of the fusion protein must be compared directly to:

- The pattern obtained from immunofluorescence staining of the endogenous, untagged protein.

- The pattern of the fusion construct with the tag at the opposite terminus [30].

- Functional Complementation (Gold Standard): Where possible, express the FP-tagged protein in a cell line where the endogenous gene has been knocked down or knocked out. The ability of the fusion protein to rescue the wild-type phenotype is the strongest evidence for its functionality [30].

Protocol: Assessing Oligomerization with the OSER Assay

The propensity of a fluorescent protein to form dimers or higher-order oligomers can cause artifactual clustering of your POI. It is crucial to use verified monomeric FPs.

- Principle: The Organized Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum (OSER) assay measures the homodimerization of FPs targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum. Dimerization leads to the formation of characteristic ER "whorls" [30].

- Procedure:

- Fuse the FP in question to an ER-targeting sequence.

- Express the construct in mammalian cells and image using confocal microscopy.

- Quantify the percentage of cells displaying ER whorls versus normal reticular ER patterns.

- Interpretation: FPs that behave as true monomers (e.g., mTurquoise2, mEGFP, mNeonGreen, mScarlet, mCherry) will show a very low incidence of whorl formation, whereas dimerizing FPs will induce this artifact in a high proportion of cells [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Fusion Protein Work

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Monomeric Fluorescent Proteins (mEGFP, mStayGold, mScarlet) [30] [33] | Genetically encoded tags for live-cell imaging with minimal aggregation | Creating functional fusion proteins for localization and dynamics studies |

| Nanobody-based Kits (e.g., GFP-Trap) [34] | High-affinity binders for specific tags; ready-to-use beads for immunoprecipitation | One-step pulldown of GFP-fusion proteins and their interactors from cell lysates |

| Proteases for Tag Cleavage (TEV Protease, Thrombin) [35] | Highly specific enzymes for removing affinity or solubilization tags after purification | Releasing the native POI from a GST or MBP fusion tag after affinity chromatography |

| Plasmid Vectors with various tags (GST, MBP, His6) [35] | Standardized systems for protein expression and purification | Rapidly cloning and expressing a POI in E. coli for in vitro biochemical assays |

Workflow and Strategy Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Fusion Protein Design and Validation

The following diagram outlines the key decision points and experimental steps in creating and validating a fluorescent protein fusion construct.

Linker Selection Logic for Fusion Protein Design

This diagram provides a logical framework for selecting the most appropriate type of peptide linker based on the desired outcome for the fusion protein.

The strategic design of protein fusions—encompassing the choice of terminal placement, the selection of a high-performance fluorescent protein, and the rational design of the connecting linker—is a cornerstone of successful experimental biology. Quantitative data demonstrates that modern FPs like mStayGold offer significant advantages in photostability for live-cell imaging. A methodical approach, which includes generating multiple constructs and implementing rigorous functional validation protocols, is highly recommended. By carefully considering these factors, researchers can create robust and reliable tools that provide accurate insights into protein function, accelerating discovery in biomedical research and drug development.

The advent of genetically encoded fluorescent proteins (FPs) has revolutionized cell biology, enabling researchers to visualize and quantify the dynamic behavior of proteins in living cells with high spatiotemporal resolution [36]. Techniques such as Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) and photoconversion have become indispensable tools for studying protein mobility, interactions, and turnover. These methods provide unique insights into fundamental biological processes including signal transduction, cytoskeletal organization, and adhesion regulation [37] [38]. The efficacy of these studies critically depends on selecting appropriate fluorescent probes with photophysical properties matched to the experimental technique and biological question. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of fluorescent proteins and their applications in monitoring dynamic cellular processes, offering researchers objective performance data to inform experimental design.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) and FLIM

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) is a powerful technique for quantifying protein-protein interactions in living cells, especially when combined with Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) [39]. This approach detects energy transfer between a donor fluorophore and an acceptor fluorophore when they are in close proximity (typically 1-10 nm), indicating molecular interactions. The fraction of donor engaged in FRET (fD) is a key parameter accessible through FLIM that quantifies the relative concentration of interacting proteins [39]. This combination is particularly valuable for revealing spatiotemporal dynamics of protein interactions in various biological systems, with recent advancements reducing acquisition times and providing detailed maps of molecular environments.

Quantitative Comparison of FRET Pairs

The sensitivity of FRET experiments depends critically on the FP pair selected. Research has systematically compared different FRET couples for FRET-FLIM experiments, testing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) linked to various red acceptors including mRFP1, mStrawberry, HaloTag (TMR), and mCherry [39]. These studies revealed that the relatively low fD percentages obtained with some models may result from spectroscopic heterogeneity of the acceptor population, partially caused by different maturation rates for donor and acceptor proteins [39].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of FRET-FLIM Protein Pairs

| Donor Protein | Acceptor Protein | Fraction of Donor in FRET (fD) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | mRFP1 | Suboptimal | Relatively low fD values that may require mathematical correction |

| EGFP | mCherry | 0.35 (minimal fD in fast acquisitions) | Frequently used despite limitations |

| mTFP1 | EYFP | 0.70 (highest of all tandems tested) | Best FRET-FLIM couple in terms of fD analysis |

| mTFP1 | mOrange | Not specified | Attractive FRET couple, though less effective than mTFP1-EYFP |

Experimental Protocols for FRET-FLIM

Wide-field Fluorescence Microscopy Setup: Experiments are typically performed using an inverted microscope equipped with piezo scanning technology and an oil immersion objective with high numerical aperture (e.g., NA 1.4) [39]. A high-resolution camera such as the CoolSnap HQ is used for acquisition, with instrumentation controlled by software such as Metamorph 6.

Time-domain Picosecond FLIM and Data Analysis: Space-resolved fluorescence lifetimes are acquired using time- and space-correlated single-photon counting (TSCSPC) detectors [39]. A mode-locked titanium sapphire laser tuned to specific wavelengths (880 nm for mTFP1 excitation, 960 nm for EGFP excitation) after frequency doubling is employed. Acquired fluorescence decays are deconvoluted with the instrument response function and fitted using algorithms such as Marquardt nonlinear least-square with specialized software.

Data Fitting Approaches: Three models are typically considered for analysis: (1) a two-species model accounting for interacting and non-interacting fractions; (2) a stretched exponential approach considering lifetime distributions from different donor-acceptor orientations; (3) a discrete double exponential for the tandem with both lifetimes free [39].

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) and FLAP

Technical Foundations and Evolution

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) involves monitoring fluorescence emission recovery within a photobleached spot to probe diffusion of fluorescently-labeled biomolecules [36]. First developed by Axelrod and Webb in 1976, FRAP has evolved through advancements in optics, charged-coupled-device (CCD) cameras, confocal microscopes, and molecular probes into a highly quantitative tool for transport and kinetic studies in the cytosol, organelles, and cell membranes [36]. A related technique, Fluorescence Loss After Photobleaching (FLAP), uses a reference fluorophore to track the distribution of photobleached molecules themselves through image differencing [38].

Comparison with Other Biophysical Techniques

Table 2: Comparison of Biophysical Techniques for Studying Protein Dynamics

| Technique | Measurable Processes | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| FRAP/FLAP | Diffusion, Convection, Reaction/Binding | Requires sophisticated models; high-powered lasers; only valid for large ROI |

| Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) | Diffusion, Reaction/Binding, Concentration | Lack of interpreting models; difficult in live cells; requires high signal-to-noise |

| Single Particle Tracking | Diffusion, Viscosity, Molecular Binding | Only for dilute species; measures lower mobility; requires feedback tracking |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Reaction/Binding, Mass transfer | Requires gold substrate; lacks interpreting models; noise from optoelectronics |

Advanced Methodologies and Mathematical Modeling

Traditional deterministic FRAP models often rely on simplifying assumptions that may not fully capture the stochastic nature of molecular interactions [38]. Recent advances include novel stochastic models based on the analytical solution of the chemical master equation to extract dynamic parameters from FRAP and FLAP experiments in complex cellular structures like focal adhesions [38]. These approaches extend beyond standard FRAP/FLAP analysis by inferring additional parameters such as protein-specific entry (kIn) and exit (kOut) rates, enabling deeper understanding of protein turnover and interactions.

Experimental Protocol for FRAP in Focal Adhesions:

- Cells are transfected with GFP-tagged FA proteins of interest (e.g., tensin 1, talin, vinculin, α-actinin)

- Photobleaching is achieved with a 488 nm laser

- Fluorescence recovery is monitored at 10-second intervals for up to 5 minutes using systems such as a DeltaVision RT microscope [38]

- Data analysis involves fitting fluorescence recovery curves to exponential functions to extract parameters including turnover rates

Figure 1: FRAP and FLAP Data Analysis Workflow

Photoconvertible Fluorescent Proteins

Principles and Protein Variants