GFP vs. Bilirubin-Binding Proteins: A Researcher's Guide to Choosing Fluorescent Tags

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and bilirubin-inducible fluorescent proteins (FPs) like UnaG, offering biomedical researchers and drug development professionals a structured framework for selecting...

GFP vs. Bilirubin-Binding Proteins: A Researcher's Guide to Choosing Fluorescent Tags

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and bilirubin-inducible fluorescent proteins (FPs) like UnaG, offering biomedical researchers and drug development professionals a structured framework for selecting the optimal tag. We explore the foundational biology, from GFP's intrinsic β-barrel structure to the fatty acid binding protein architecture of bilirubin-binding FPs. The scope extends to methodological applications in live-cell imaging, biosensors, and therapeutic cell tracking, alongside troubleshooting for common challenges like anaerobic conditions, acidic environments, and autofluorescence. A direct, evidence-based comparison validates the performance of each system, empowering scientists to make informed decisions for their specific experimental or clinical contexts.

Illuminating the Core: Structural and Mechanistic Foundations of Fluorescent Proteins

The discovery and development of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria revolutionized molecular and cellular biology, providing researchers with a genetically encodable fluorescent marker that functions without exogenous cofactors [1]. The iconic GFP structure—an 11-stranded β-barrel surrounding a central chromophore—has become a paradigm for understanding how protein architecture can confer remarkable fluorescence properties [2] [3]. This scaffold protects the chromophore from non-radiative decay, allowing efficient fluorescence emission [4]. Within this structural paradigm, a new class of fluorescent proteins has emerged that leverages similar β-barrel scaffolds but operates through fundamentally different mechanisms. Bilirubin-inducible fluorescent proteins, notably UnaG discovered in the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica, represent a significant divergence from the GFP model, utilizing ligand binding rather than autocatalytic chromophore formation to generate fluorescence [5] [6] [7]. This comparative analysis examines the structural foundations, photophysical properties, and experimental applications of these distinct yet structurally related fluorescent protein families, providing researchers with objective data to inform their selection for specific investigative contexts.

Structural Foundations and Fluorescence Mechanisms

The GFP Family: Intrinsic Chromophore Formation

The GFP β-barrel scaffold encloses a chromophore that forms autocatalytically from three consecutive amino acids (X65-Tyr66-Gly67) within the polypeptide chain [2] [1]. This post-translational modification involves cyclization, dehydration, and oxidation reactions that create an extended π-conjugated system responsible for light absorption and emission [3] [1]. The mature chromophore, 4-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)-1,2-dimethyl-imidazolinone (p-HOBDI), is deeply embedded within the β-barrel, where it is shielded from the aqueous environment and its rotational freedom is restricted, thereby enabling high fluorescence quantum yield [4]. A critical limitation of conventional GFP-like proteins is their absolute requirement for molecular oxygen to complete the chromophore maturation process, which precludes their use in anaerobic systems [8].

UnaG and Bilirubin-Binding Proteins: Ligand-Induced Fluorescence

UnaG belongs to the fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) family and features a β-barrel structure that transiently binds bilirubin (BR) as an exogenous fluorophore [5] [6] [7]. Unlike GFP, UnaG in its apo state (apoUnaG) is non-fluorescent; fluorescence emerges only upon formation of the holoUnaG complex with bilirubin [5] [7]. The UnaG-bilirubin interaction is characterized by high specificity, with the ligand protected from solvent within the protein barrel by a conserved glycine-proline-proline (GPP) motif [6]. This ligand-binding mechanism operates independently of oxygen, enabling fluorescence applications in anaerobic environments where GFP cannot function [8]. Recent research has revealed that holoUnaG exists in two distinct fluorescence states (holoUnaG1 and holoUnaG2) that reach equilibrium through a reversible intramolecular reaction, with the brighter holoUnaG2 state exhibiting approximately fourfold greater molecular brightness [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Structural and Functional Characteristics

| Characteristic | GFP Family | UnaG/Bilirubin-Binding FPs |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Scaffold | 11-stranded β-barrel [2] [3] | β-barrel typical of FABP family [5] [6] |

| Chromophore Origin | Autocatalytic from internal tripeptide [2] [1] | Exogenous ligand (bilirubin) [5] [7] |

| Maturation Requirement | Oxygen-dependent oxidation [8] | Oxygen-independent binding [8] |

| Apo-State Fluorescence | Non-fluorescent until matured | Non-fluorescent without ligand [5] [7] |

| Key Conserved Motifs | Ser65-Tyr66-Gly67 (or variants) [2] | Glycine-Proline-Proline (GPP) loop [6] |

| Maturation Time | Minutes to hours [9] | Instantaneous upon ligand binding [5] |

Comparative Photophysical Properties

The practical utility of fluorescent proteins in research depends critically on their photophysical characteristics, which determine their brightness, spectral profile, and stability under experimental conditions. Quantitative comparison of these parameters enables researchers to match protein properties to application requirements.

Table 2: Photophysical Properties and Performance Metrics

| Parameter | GFP (EGFP) | UnaG | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Maximum (nm) | ~488 [9] | 496-498 [5] [6] | In vitro spectroscopic measurement |

| Emission Maximum (nm) | ~507 [9] | 527-532 [5] [6] | In vitro spectroscopic measurement |

| Quantum Yield (%) | ~50-60 [5] | ~50 [5] | Comparison to known standards |

| Maturation Rate | Minutes to hours [9] | Instantaneous [5] | Time from synthesis to fluorescence |

| Brightness Ratio (States) | N/A | 1:3.9 (holoUnaG1:holoUnaG2) [5] | Photon counting statistics |

| Oxygen Requirement | Essential [8] | None [8] | Anaerobic bacterial imaging |

| Thermal Stability | High (denatures ~65-70°C) [3] | Moderate (mutants alter stability) [7] | Circular dichroism melting curves |

The data reveal that UnaG achieves quantum efficiency comparable to enhanced GFP (approximately 50%) despite their different fluorescence mechanisms [5]. UnaG's instantaneous activation upon bilirubin binding provides a significant advantage for time-sensitive applications, unlike GFP's slower maturation process. The recently discovered two-state system in UnaG adds complexity to its photophysical behavior, with the equilibrium favoring the brighter holoUnaG2 state (6:4 population ratio) [5]. From a practical standpoint, UnaG's oxygen independence enables applications in anaerobic environments that are inaccessible to GFP [8].

Experimental Applications and Methodologies

GFP-Based Experimental Workflows

GFP and its engineered variants have enabled diverse experimental approaches in live-cell imaging and protein dynamics. The protein's tolerance to circular permutation and genetic fusion has been particularly valuable for biosensor design [9]. Split-GFP systems represent another significant application, where fragments of GFP only reassemble into fluorescent complexes when fused to interacting protein partners [9]. This protein-fragment complementation assay (PCA) approach has become a powerful tool for detecting protein-protein interactions in living cells.

UnaG Experimental Protocols and Biosensor Implementation

The following detailed protocol for UnaG expression, purification, and fluorescence analysis provides researchers with a methodology for implementing this bilirubin-inducible system:

Protein Expression and Purification [5] [7]:

- Clone UnaG gene into pColdI vector with N-terminal 6xHis tag

- Transform into BL21 E. coli cells and culture in lysogeny broth with ampicillin (100 μg/mL)

- Induce expression with 0.5 mM IPTG at 16°C for 18 hours

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and lyse via sonication in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5)

- Purify using HisTrap HP column with imidazole gradient (20-500 mM)

- Desalt into storage buffer using PD-10 column

Fluorescence Titration for Bilirubin Binding [5] [7]:

- Prepare UnaG samples in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5)

- Titrate with bilirubin stock solution (1 mM in DMSO)

- Measure fluorescence emission at 527-532 nm with excitation at 496 nm

- Plot fluorescence intensity against bilirubin concentration

- Calculate dissociation constant (Kd) using nonlinear regression analysis

Anaerobic Imaging Applications [8]:

- Culture anaerobic bacteria (e.g., Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron) expressing UnaG

- Add bilirubin (25 μM final concentration) to growth media

- Transfer cells to anaerobic microscopy chamber

- Image using standard GFP filter sets without oxygen exposure

Molecular engineering of UnaG has created variants with altered binding affinity and fluorescence properties. For example, R112M, R132M, and double R112&132M mutations reduce polarity at bilirubin-binding sites, resulting in shifted excitation and emission profiles and modified thermal stability [7]. These engineered variants expand UnaG's utility as a quantitative biosensor for bilirubin detection, with potential clinical applications in diagnosing hyperbilirubinemia and related neurological disorders [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Experimental Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent/Method | Function/Role | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin (BR) | Fluorogenic ligand for UnaG [5] [8] | Prepared as 1 mM stock in DMSO [5] |

| Biliverdin (BV) | Ligand for far-red BBFPs like IFP2.0 [8] | Anaerobic multi-color imaging [8] |

| Analytical Ultracentrifugation | Determine oligomeric state [5] | Confirm monomeric state of apoUnaG and holoUnaG [5] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Engineer UnaG variants [7] | Modify bilirubin binding affinity and spectral properties [7] |

| Photon Counting Analysis | Quantify brightness states [5] | Resolve holoUnaG1 and holoUnaG2 populations [5] |

| Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy | Analyze secondary structure and stability [7] | Monitor thermal denaturation of UnaG variants [7] |

| Far-Red BBFPs (IFP2.0) | Anaerobic compatible partner for multicolor work [8] | Distinguish multiple bacterial species in co-culture [8] |

The comparative analysis of GFP and bilirubin-binding fluorescent proteins reveals a complementary relationship rather than a competitive one in the researcher's toolkit. GFP remains the superior choice for standard aerobic cellular imaging where genetic encoding and autonomous fluorescence are paramount. Its well-engineered variants and extensive validation across model systems provide a reliable platform for most fluorescence applications. Conversely, UnaG and related BBFPs offer unique capabilities for specialized investigations: anaerobic systems, rapid detection assays, and quantitative bilirubin sensing. UnaG's oxygen-independent fluorescence enables real-time imaging of previously inaccessible biological environments, particularly anaerobic microbial communities [8]. The ligand-inducible nature of UnaG provides both an advantage in temporal control and a limitation in maintaining consistent fluorescence during prolonged experiments. As protein engineering continues to advance both protein families, the strategic selection between intrinsic and induced fluorescence paradigms will depend on specific experimental requirements, environmental constraints, and measurement objectives.

The discovery and development of genetically encoded fluorescent tags have revolutionized biological imaging, enabling researchers to visualize protein localization, dynamics, and interactions in living cells and organisms [10]. While intrinsically fluorescent proteins like GFP and its variants dominate biological imaging applications, a distinct class of ligand-induced fluorescent proteins (LIFPs) has emerged with unique advantages for specialized applications [5] [10]. Among these, bilirubin-binding fluorescent proteins represent a specialized category of extrinsic fluorescent tags that derive their fluorescence from binding bilirubin, an endogenous tetrapyrrole chromophore [7] [6]. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis between conventional GFP-like proteins and bilirubin-binding proteins, with specific focus on UnaG, the prototypical bilirubin-inducible fluorescent protein from the Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica).

Fundamental Mechanisms: Intrinsic versus Ligand-Induced Fluorescence

GFP and Intrinsically Fluorescent Proteins

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) and its homologs are intrinsically fluorescent proteins that form their fluorophore autocatalytically from internal amino acids within an 11-stranded β-barrel structure [10]. This fluorophore formation requires molecular oxygen and can take from minutes to days depending on the specific protein, which represents a significant limitation for anaerobic applications or rapid labeling needs [10]. The fluorescence mechanism is entirely self-contained within the folded protein structure, requiring no external cofactors beyond oxygen.

Bilirubin-Binding Proteins as Ligand-Induced Fluorescent Proteins

In contrast, bilirubin-binding proteins such as UnaG belong to the fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) family and remain non-fluorescent in their apo state (apoUnaG) [5] [7]. Fluorescence is induced only upon binding of unconjugated bilirubin (UC-BR) within the protein's β-barrel structure [7] [11]. This binding occurs with high specificity for the unconjugated form of bilirubin and creates the fluorescent holoUnaG complex [11]. The fluorescence activation mechanism involves an instantaneous, oxygen-independent formation of the fluorophore, a significant advantage over GFP-family proteins [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Fluorescent Protein Classes

| Characteristic | GFP-like Proteins | Bilirubin-Binding Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorophore Origin | Autocatalytic from internal amino acids | External bilirubin ligand |

| Oxygen Requirement | Required for fluorophore maturation | Not required |

| Maturation Time | Several minutes to days | Instantaneous upon bilirubin binding |

| Native Structure | β-barrel | β-barrel with α-helical domains |

| Baseline Fluorescence | Constitutive | Inducible by ligand binding |

Molecular and Spectral Properties: A Detailed Comparison

Structural Characteristics

UnaG shares the fundamental β-barrel structural motif with GFP, though it belongs to the FABP family rather than the GFP superfamily [7]. The UnaG protein has a molecular weight of 15.6 kDa and comprises 139 amino acids folded into a β-barrel structure with three alpha helical domains [7]. The bilirubin binding pocket contains critical arginine residues (R112 and R132) that participate in bilirubin binding through their guanidino groups [7]. Mutation studies demonstrate that replacing these arginine residues with methionine significantly alters bilirubin binding affinity and spectral properties [7].

Spectral Properties and Quantum Efficiency

The UnaG-bilirubin complex (holoUnaG) exhibits green fluorescence with excitation and emission maxima at approximately 498 nm and 527 nm, respectively [7] [11]. The quantum efficiency of holoUnaG is remarkably high at approximately 50%, comparable to enhanced GFP (EGFP), one of the brightest GFP mutants [5]. Recent research has revealed that holoUnaG exists in two distinct fluorescence states (holoUnaG1 and holoUnaG2) that reach equilibrium after initial complex formation, with a molecular brightness ratio of 1:3.9 and equilibrium population ratio of 6:4 [5].

Table 2: Spectral Properties Comparison

| Parameter | EGFP | UnaG | GymFP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Maximum (nm) | 488 | 498 | 496 |

| Emission Maximum (nm) | 507 | 527 | 532 |

| Quantum Yield | 0.60 | ~0.50 | Not reported |

| Extinction Coefficient (mM⁻¹cm⁻¹) | 56 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Brightness (Quantum Yield × Extinction Coefficient) | 33.6 | Comparable to EGFP | Not reported |

| Maturation Time | Hours | Instantaneous | Instantaneous |

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Bilirubin Detection and Quantification

The high specificity of UnaG for unconjugated bilirubin has been harnessed for clinical detection applications. A robust protocol for serum bilirubin measurement involves incubating serum samples with purified UnaG protein and measuring fluorescence intensity, which shows linear correlation with bilirubin concentrations from 0 to 70 mg/dL [11]. This method demonstrates exceptional precision with coefficients of variation <10% and remains unaffected by common serum interferents like hemoglobin or lipid emulsion [11]. The technique has been successfully validated in newborn serum samples, demonstrating strong correlation (r = 0.943, P < 0.001) with conventional bilirubin oxidase methods [11].

Protein Engineering and Mutant Development

Protein engineering efforts have generated UnaG variants with modified properties. The R112M, R132M, and R112&132M mutants show altered spectral properties, with the double mutant exhibiting a pronounced blue shift in excitation (504 nm) and emission (542 nm) peaks [7]. These mutations also affect thermal stability, with the R112M mutant demonstrating the lowest melting temperature (53.8°C) among the variants [7]. Another engineered variant, eUnaG, exhibits approximately twice the fluorescence intensity of wild-type UnaG through modification of the valine amino acid at position 2 [7].

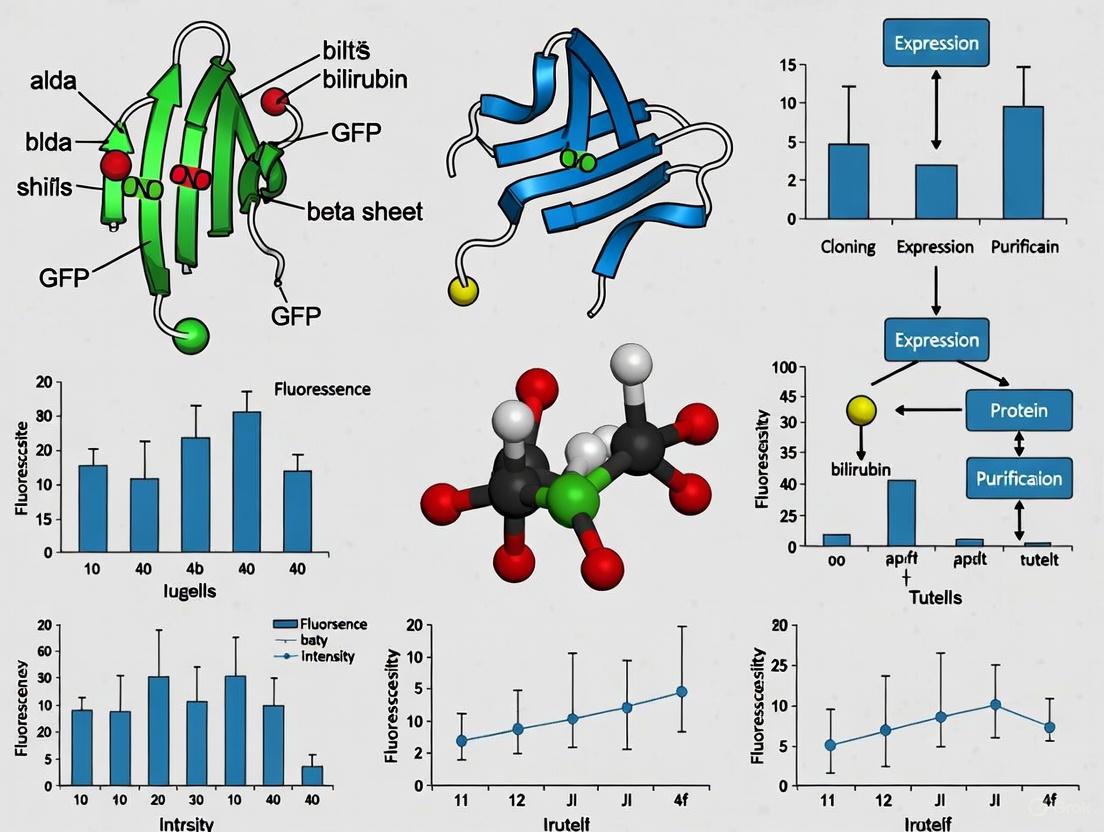

Diagram 1: UnaG Fluorescence Activation Pathway. This diagram illustrates the transition from non-fluorescent ApoUnaG to the two distinct fluorescent states of HoloUnaG upon bilirubin binding, culminating in an equilibrium state between the two forms.

Advantages and Limitations in Research Applications

Unique Advantages of Bilirubin-Binding Proteins

- Oxygen-Independent Maturation: Unlike GFP, UnaG fluorescence activation doesn't require molecular oxygen, enabling applications in anaerobic conditions and hypoxic environments [5].

- Instantaneous Activation: Fluorescence develops immediately upon bilirubin binding, unlike GFP variants that require time for fluorophore maturation [5].

- Endogenous Fluorophore Utilization: Can leverage naturally occurring bilirubin in biological systems, potentially enabling monitoring of heme catabolism pathways [12].

- Specific Biosensing Capability: The specific binding to unconjugated bilirubin enables direct development as a biosensor for this clinically relevant molecule [11].

Practical Limitations and Challenges

- Dependence on Bilirubin Availability: Fluorescence is contingent upon bilirubin presence and proper delivery to the cellular compartment of interest [7].

- Potential Endogenous Interference: In systems with natural bilirubin fluctuations, background signals may complicate interpretation [12].

- Limited Color Palette: Currently, bilirubin-binding proteins are primarily green-emitting, unlike the broad color palette of GFP variants [10].

- Relatively New Technology: Less established and characterized compared to the extensive toolkit of GFP variants and applications [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bilirubin-Binding Protein Work

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pColdI-UnaG, pTolT-UnaG, pGEX-UnaG | Recombinant protein expression in E. coli systems [5] [7] |

| Chromophore | Unconjugated bilirubin (UC-BR) | Fluorophore ligand for activating fluorescence [5] [7] |

| Purification Systems | HisTrap HP column (for 6×His-tagged UnaG) | Affinity purification of recombinant proteins [5] |

| Mutagenesis Kits | Phusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Creating specific UnaG mutants [7] |

| Spectroscopic Tools | Fluorescence spectrophotometer (e.g., Hitachi F-7100) | Measuring excitation/emission spectra and binding kinetics [7] |

| Structural Analysis | Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy | Assessing secondary structure and thermal stability [7] |

Diagram 2: UnaG Protein Engineering Workflow. This experimental workflow outlines the key steps in generating and characterizing UnaG variants, from gene synthesis to spectroscopic analysis.

Bilirubin-binding proteins represent a distinct class of extrinsic fluorescent tags with unique mechanisms and applications that complement conventional GFP-like proteins. Their oxygen-independent, instantaneous activation and specific binding to an endogenous ligand provide unique advantages for specialized applications including hypoxia imaging, bilirubin sensing, and rapid protein tagging [5] [11]. While the GFP toolkit offers broader color options and more established protocols, bilirubin-binding proteins like UnaG and newly discovered homologs such as GymFP from the moray eel (Gymnothorax zonipectis) expand the fluorescent protein arsenal with novel functionalities [6]. Future directions include engineering brighter variants, expanding the spectral range, and developing optimized delivery systems for bilirubin in cellular environments. For researchers considering these tools, bilirubin-binding proteins offer the greatest advantage in applications involving hypoxic conditions, rapid labeling requirements, or when leveraging bilirubin as a biological signal.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) are indispensable tools in biological research, enabling the visualization of cellular processes in real time. Despite their similar functional output—the emission of light—these proteins achieve fluorescence through fundamentally different biochemical pathways. This guide provides a structured comparison between two principal classes of fluorescent proteins: those with autocatalytic maturation, exemplified by the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), and those with cofactor-dependent activation, such as bilirubin-binding proteins including UnaG. The core distinction lies in the origin of their chromophores; GFP self-assembles its chromophore from its own amino acids, while UnaG must bind an externally synthesized ligand, bilirubin, to become fluorescent. This article objectively compares their performance, detailing underlying mechanisms, experimental workflows, and key reagent solutions for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Chromophore Formation

The genesis of the light-emitting chromophore is the critical event that confers fluorescence. The pathways for GFP-like proteins and bilirubin-binding FPs are distinct, involving either an internal synthesis or an external binding process.

Autocatalytic Maturation in Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) The GFP chromophore is formed post-translationally from three consecutive amino acids within its own polypeptide chain (Ser65–Tyr66–Gly67 in Aequorea victoria GFP) [13]. This process is autocatalytic, requiring only molecular oxygen and proceeding without the need for external enzymes or cofactors [13]. The generally accepted mechanism involves a series of internal reactions within the folded protein: cyclization, dehydration, and oxidation [14]. Theoretical studies using hybrid density functional theory (B3LYP) indicate that the rate-limiting cyclization step is initiated by the deprotonation of the Gly67 amide nitrogen, a process facilitated by the protein's internal environment, including residues Arg96 and Glu222 acting as a general base [14]. This creates an extended π-conjugation system within the imidazolinone ring, enabling light absorption and emission.

Cofactor-Dependent Activation in Bilirubin-Binding Proteins (UnaG) In stark contrast, fluorescent proteins like UnaG, discovered in the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica, belong to the fatty acid binding protein family and are not intrinsically fluorescent [7] [6]. Their fluorescence is induced upon the highly specific, non-covalent binding of an external chromophore, bilirubin [7]. Bilirubin is a linear tetrapyrrole molecule produced from the catabolism of heme in vertebrates [7]. The apo form of UnaG (apoUnaG) does not fluoresce. Upon binding bilirubin, it forms the holo complex (holoUnaG), which emits bright green light (peak emission at 527 nm) [7]. The binding affinity is high, with dissociation constants ((K_d)) in the nanomolar range, and is stabilized by specific amino acid interactions, such as arginine residues R112 and R132 in wild-type UnaG [7].

The diagrams below summarize these two fundamental pathways and their key characteristics.

Figure 1: Comparative chromophore genesis pathways. GFP undergoes an internal, multi-step maturation process, while UnaG requires the binding of an externally produced bilirubin molecule to become fluorescent.

Experimental Analysis & Workflows

Studying these proteins requires tailored experimental approaches to probe their distinct maturation, stability, and spectral properties.

Probing GFP's Autocatalytic Mechanism

The study of GFP maturation often involves site-directed mutagenesis to alter key chromophore residues, followed by spectroscopic analysis and theoretical calculations.

- In Silico Mechanism Studies: Cluster models based on X-ray crystal structures (e.g., PDB: 2AWJ) are used with hybrid density functional theory (e.g., B3LYP) to calculate potential energy profiles for cyclization. This allows researchers to compare the energy barriers of different proposed mechanisms, such as cyclization initiated by deprotonation of the Gly67 amide nitrogen versus the Tyr66 α-carbon [14].

- In-Gel Fluorescence Detection: A key practical protocol involves detecting GFP fluorescence directly in SDS-PAGE gels, known as In-Gel Fluorescence (IGF). The robust β-barrel structure of GFP and its derivatives allows them to retain fluorescence even after denaturation in SDS sample buffer at high temperatures [15].

- Workflow: Cell extracts expressing GFP-fusion proteins are prepared with standard Laemmli buffer, heated (95°C, 5-10 min), and loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel is immediately imaged using a standard fluorescence imager with appropriate filters (e.g., 488 nm excitation/510 nm emission) without the need for protein transfer or antibody staining [15].

- Application: This protocol is used for rapid verification of fusion protein integrity, quantification, and screening, offering high sensitivity and a broad dynamic range with minimal background [15].

Characterizing UnaG-Bilirubin Interaction

Analyzing bilirubin-binding FPs focuses on the protein-ligand interaction, structural changes upon binding, and tuning of biophysical properties.

- Ligand Binding and Spectroscopic Characterization: The core protocol involves titrating a purified, non-fluorescent apoUnaG protein sample with increasing concentrations of bilirubin and monitoring the emergence of fluorescence.

- Workflow: Purified apoUnaG (from recombinant expression in E. coli) is diluted in a suitable buffer. A concentrated stock solution of bilirubin (in DMSO or NaOH) is added in increments. After each addition, the fluorescence emission spectrum (e.g., 500-600 nm, with excitation at ~490 nm) is recorded. The fluorescence intensity at the emission maximum (~530 nm) is plotted against the bilirubin concentration to determine the dissociation constant ((K_d)) [7].

- Mutagenesis to Modulate Function: Site-directed mutagenesis of key bilirubin-binding residues is performed to engineer UnaG variants. For instance, mutating arginine residues (R112, R132) to methionine reduces polarity in the binding pocket, which can alter the excitation/emission peaks, binding affinity ((K_d)), and thermal stability of the protein [7].

- Structural Stability Assessment: The impact of bilirubin binding on protein structure is assessed using Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy in the far-UV region (190-250 nm). This technique compares the secondary structure of apoUnaG (often showing low ellipticity and poor defined structure) with holoUnaG (showing characteristic α-helical and β-sheet signatures), confirming that ligand binding induces proper folding [7].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for characterizing a bilirubin-inducible fluorescent protein like UnaG.

Figure 2: Core workflow for characterizing a bilirubin-inducible fluorescent protein. The process from gene identification to biophysical analysis enables the determination of key functional parameters.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of GFP and UnaG, highlighting their differences for research applications.

Table 1: Performance comparison of autocatalytic GFP and cofactor-dependent UnaG.

| Feature | Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Bilirubin-Binding Protein (UnaG) |

|---|---|---|

| Chromophore Origin | Autocatalytic (Internal Ser-Tyr-Gly) [13] | Exogenous ligand (Bilirubin) [7] |

| Maturation Requirement | Molecular oxygen (O₂) [13] | Binding of bilirubin [7] |

| Typical Excitation/Emission | Ex ~488 nm / Em ~509 nm (for EGFP) [13] | Ex ~496 nm / Em ~527 nm [6] |

| Fluorescence Quantum Yield | 0.60 (EGFP) [13] | 0.51 (Wild-type UnaG, varies by mutant) [7] |

| Extinction Coefficient (ε) | ~55,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ (EGFP) [13] | Information not specified in results |

| Ligand Dissociation Constant ((K_d)) | Not applicable | Nanomolar range (e.g., ~98 nM for R132M UnaG mutant) [7] |

| Key Advantage | No external cofactor needed; self-sufficient | High specificity for bilirubin; usable as biosensor |

| Key Limitation | Slow maturation at lower temperatures; sensitivity to pH (wtGFP) | Dependent on bilirubin availability and concentration |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Successful experimentation with these fluorescent proteins requires a specific set of reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for studying fluorescent protein maturation and function.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces point mutations into gene sequences to study chromophore formation or ligand binding. | Engineering GFP chromophore mutants (S65T) [13] or UnaG binding pocket mutants (R112M) [7]. |

| pBAD/His Expression Vector | Allows tightly controlled, inducible recombinant expression of proteins in E. coli. | Expression of UnaG and its mutant variants for purification [7]. |

| Bilirubin Stock Solution | The essential ligand for activating fluorescence in UnaG and related proteins. | Titration into apoUnaG for fluorescence characterization and (K_d) determination [7]. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer | Measures the excitation and emission spectra of fluorescent samples; quantifies intensity. | Determining the (λ{ex}/λ{em}) maxima and quantum yield of GFP and UnaG [7]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrometer | Analyzes the secondary structure and stability of proteins in solution. | Confirming the structural change in UnaG upon bilirubin binding and assessing thermal stability [7]. |

| SDS-PAGE Gel Electrophoresis System | Separates proteins by molecular weight; used with in-gel fluorescence (IGF) detection. | Rapidly verifying the expression and integrity of GFP-fusion proteins directly in gels [15]. |

Discussion & Research Implications

The choice between autocatalytic and cofactor-dependent fluorescent proteins is fundamental and depends on the research context. Each system presents unique advantages and challenges that direct their application.

GFP and its engineered variants (e.g., EGFP, sfGFP) offer a self-contained system. Their ability to fold and form a chromophore autonomously in diverse cellular environments makes them exceptionally versatile for general-purpose tagging and reporting in live cells [13]. However, their maturation can be slow and is sensitive to the cellular environment, such as pH and redox potential [13]. The robust, covalent nature of its chromophore also allows for direct detection in denaturing SDS-PAGE gels (IGF), a significant advantage for biochemical analyses [15].

In contrast, the bilirubin-dependent fluorescence of UnaG defines a specialized niche. Its absolute requirement for an endogenous metabolite makes it a powerful biosensor for bilirubin, with direct applications in diagnosing liver function and jaundice [7]. The ligand-induced fluorescence provides a "switch-on" mechanism, eliminating background from unbound apo-protein. This property is being exploited to develop rapid, inexpensive, and specific clinical detection methods for bilirubin [7]. Furthermore, the discovery of UnaG homologs in other eels, like GymFP from the moray eel, demonstrates the natural diversity and evolutionary expansion of this protein family [6].

From a protein engineering perspective, the two systems offer different handles for optimization. GFP is typically engineered by mutating residues around the chromophore to alter its color, brightness, and stability [13]. UnaG, however, can be tuned by mutating residues involved in bilirubin binding (e.g., R112, R132) to modulate its affinity, spectral shift, and thermal stability, as demonstrated in recent studies [7].

In conclusion, the dichotomy between autocatalytic and cofactor-dependent maturation underpins the functional diversity of the fluorescent protein toolkit. While GFP remains a cornerstone for generic cellular imaging, bilirubin-binding proteins like UnaG are emerging as highly specific biosensors, opening new avenues in biomedical diagnostics and fundamental research.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized molecular and cellular biology, enabling researchers to visualize dynamic processes within living systems. Since the discovery of the original Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) from Aequorea victoria, the FP toolbox has expanded dramatically to include proteins with diverse spectral properties and biochemical characteristics. These proteins can be broadly categorized by their chromophore type and source. The classic GFP-like proteins form their chromophores through an autocatalytic process requiring oxygen, while a newer class of proteins binds to exogenous or endogenous fluorogenic chromophores such as bilirubin, biliverdin, or flavins. This diversity provides researchers with a rich palette of tools for imaging, each with unique advantages and limitations in terms of brightness, spectral range, and environmental requirements.

The quest for spectral diversity is driven by the need for multi-color imaging, deeper tissue penetration, and compatibility with different microscope systems and experimental conditions. Brightness, a product of a protein's extinction coefficient and quantum yield, is a critical parameter determining the signal-to-noise ratio in fluorescence imaging. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance characteristics across different fluorescent protein systems, with a specific focus on GFP versus bilirubin-binding fluorescent proteins, to assist researchers in selecting the optimal probes for their experimental needs.

Performance Comparison of Fluorescent Protein Systems

The table below summarizes the key photophysical properties of major fluorescent protein classes, providing a quantitative basis for comparison.

Table 1: Photophysical Properties of Major Fluorescent Protein Classes

| Protein Class | Example Protein | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Quantum Yield | Molecular Brightness* | Oxygen Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFP-like | sfGFP | 485 | 510 | 83,000 [16] | 0.65 [16] | 53,950 | Yes |

| GFP-like (Enhanced) | YuzuFP | 485 | 510 | ~90,000 [16] | ~0.72 [16] | ~64,800 | Yes |

| Bilirubin-binding | UnaG | 498 | 527 | 77,900 [5] | 0.51 [5] | 39,729 | No [8] [17] |

| Bilirubin-binding | GymFP | 496 | 532 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | No [6] |

| Biliverdin-binding | IFP2.0 | 690 | 711 | 82,000 [8] | 0.08 [8] | 6,560 | No [8] |

| Biliverdin-binding (Triad) | BDFP1.1:3.1:1.1 | ~650-700 (FR) | 722 | Not specified | Not specified | High (in cells) [18] | No [18] |

| Flavin-binding | miniGFP1/2 | 450 | 499 | ~46,000 [19] | ~0.60 [19] | ~27,600 | No [19] |

Note: Molecular Brightness is calculated as the product of Extinction Coefficient and Quantum Yield, normalized to the value for EGFP (often set to 1.0 in literature). The values here are approximate for cross-comparison. FR = Far-Red light.

Analysis of Performance Data

The quantitative data reveals clear trade-offs between different fluorescent protein systems. GFP-like proteins, particularly enhanced variants like YuzuFP, generally offer the highest molecular brightness in the green-yellow spectrum, with improvements achieved through mutations that optimize chromophore interaction networks [16]. For instance, the H148S mutation in YuzuFP increases persistent hydrogen bonding with the chromophore and water residency time, resulting in a 1.5-fold brightness increase and 3-fold enhanced photobleaching resistance compared to sfGFP [16].

Bilirubin-binding proteins like UnaG and GymFP provide strong green fluorescence with the significant advantage of oxygen-independent maturation [6] [8] [17]. While UnaG's quantum yield (0.51) is moderately high, its practical brightness in mammalian cells is comparable to GFP because it utilizes endogenous bilirubin [5] [17]. These proteins exhibit instantaneous fluorescence upon bilirubin binding without the delay required for GFP chromophore oxidation [5].

Near-infrared systems based on biliverdin binding, such as the BDFP triad, offer emission in the tissue-penetrating spectral window (700-770 nm) but often at the cost of reduced quantum yield, as seen with IFP2.0 (0.08) [18] [8]. Engineered systems that employ FRET between biliverdin- and phytochromobilin-binding domains can overcome this limitation, achieving both large red-shift and high brightness in mammalian cells [18].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Live-Cell Anaerobic Imaging Using Bilirubin-Binding Proteins

Purpose: To enable fluorescence imaging of protein dynamics and localization in obligate anaerobic bacteria, such as those found in the gut microbiome, where conventional GFP-like proteins fail to mature [8].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strains: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) or other anaerobic species.

- Plasmids: Expression vectors encoding UnaG (cytoplasmic or fusion constructs).

- Ligand Solution: 25 mM bilirubin stock in DMSO [8].

- Growth Media: Rich media (tryptone-yeast extract-glucose) and minimal media with carbohydrate source (0.05% w/v glucose or maltose) [8].

- Anaerobic Chamber: Coy chamber or equivalent maintaining anaerobic atmosphere (typically 85% N₂, 10% CO₂, 5% H₂) [8].

Method:

- Transformation: Introduce the UnaG expression plasmid into B. theta via electroporation or conjugation.

- Culture Inoculation: Pick single colonies and inoculate 5 mL of rich media containing appropriate antibiotic. Grow anaerobically at 37°C for 24-48 hours.

- Back Dilution: Dilute the culture 1:100 into fresh minimal media containing 25 µM bilirubin [8].

- Anaerobic Growth: Grow cells anaerobically to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ~0.4-0.6).

- Microscopy Preparation: Transfer a small aliquot of cells (~2 µL) to a glass coverslip. Seal with a second coverslip using epoxy adhesive to maintain anaerobic conditions during imaging [8].

- Image Acquisition: Image cells using standard GFP filter sets (excitation ~470-490 nm, emission ~500-540 nm) on an epifluorescence or confocal microscope.

Technical Notes: Bilirubin is light-sensitive and should be handled in dim light. DMSO concentrations in media should be kept below 1% to avoid toxicity. For two-color anaerobic imaging, IFP2.0 (a biliverdin-binding protein) can be co-expressed and visualized using far-red filter sets [8].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Bilirubin Binding Kinetics and Fluorescence States

Purpose: To quantitatively analyze the binding interaction between UnaG and its bilirubin ligand, including the discovery and characterization of distinct fluorescent states [5].

Materials:

- Purified Protein: Recombinant 6xHis-tagged UnaG protein purified via immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) [5].

- Ligand: 1 mM bilirubin stock solution in DMSO (store at -20°C protected from light) [5].

- Buffers: 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 [5].

- Instrumentation: Spectrofluorometer, analytical ultracentrifuge [5].

Method:

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify UnaG from E. coli. Determine protein concentration spectrophotometrically.

- Fluorescence Time Course: Rapidly mix UnaG (final concentration 1 µM) with bilirubin (final concentration 1.5 µM) in potassium phosphate buffer. Immediately monitor fluorescence intensity (excitation 500 nm, emission 527 nm) over time [5].

- State Differentiation: Observe the biphasic fluorescence increase, indicative of the formation of two distinct states: the initial holoUnaG1 and the brighter, final holoUnaG2 [5].

- Equilibrium Analysis: After signal stabilization, measure the excitation and emission spectra of the mature holoUnaG complex.

- Quenching Experiments: Add a known concentration of a competing bilirubin-binding molecule (e.g., human serum albumin) to the mature holoUnaG complex and monitor fluorescence decrease to estimate dissociation rates [5].

- Oligomeric State Verification: Perform analytical ultracentrifugation sedimentation equilibrium analysis (AUC-SE) to confirm UnaG exists as a monomer in solution [5].

Technical Notes: The molecular brightness ratio of holoUnaG1 to holoUnaG2 is approximately 1:3.9, with an equilibrium population ratio of about 6:4 [5]. The intra-molecular reaction converting the two states is reversible and associated with a change in the chromophore environment rather than a chemical modification of bilirubin itself [5].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences in how GFP-like proteins and bilirubin-binding proteins achieve fluorescence, which underpins their distinct experimental applications.

Diagram 1: Contrasting fluorescence activation pathways between GFP-like and bilirubin-binding proteins. The key distinction is the oxygen-dependent chromophore maturation in GFP versus the instantaneous, oxygen-independent ligand binding in bilirubin-binding proteins.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials and their applications for working with different fluorescent protein systems, serving as a quick-reference guide for experimental planning.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescent Protein Applications

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin | Fluorogenic ligand for UnaG, GymFP, and related bilirubin-binding FPs [5] [8] | Anaerobic live-cell imaging [8]; BR distribution studies [5] |

| Biliverdin | Fluorogenic ligand for near-infrared FPs (IFP2.0, BDFPs) [18] [8] | Deep-tissue imaging; multi-color anaerobic studies with UnaG [8] |

| Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) | Endogenous chromophore for flavin-binding FPs (FbFPs, miniGFPs) [19] [17] | Hypoxia and anaerobic imaging; metal ion biosensing [19] |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Maintains oxygen-free environment for culture and imaging of obligate anaerobes [8] | Gut microbiome research; studies of anaerobic pathogens [8] |

| Superfolder GFP (sfGFP) | Robust, fast-folding GFP variant; baseline for engineering and comparison [16] | General protein tagging in aerobic conditions; reference standard for brightness [16] |

| HaloTag System | Chemical-genetic tagging system for anaerobic single-particle tracking [8] | Protein dynamics in anaerobic bacteria when expressed FPs are unsuitable [8] |

The expanding spectral diversity of fluorescent proteins provides researchers with an increasingly sophisticated toolkit for biological imaging. GFP-like proteins continue to be optimized for brightness and photostability through rational design and molecular dynamics-guided engineering, as demonstrated by variants like YuzuFP [16]. Simultaneously, bilirubin- and biliverdin-binding proteins offer unique capabilities for anaerobic imaging and deeper tissue penetration, albeit sometimes with compromises in absolute quantum yield.

The choice between these systems is fundamentally application-dependent. For standard aerobic cell culture with maximal brightness in the green spectrum, enhanced GFP variants remain superior. However, for investigating anaerobic microbiomes, hypoxic tumor environments, or for deep-tissue imaging requiring near-infrared emission, bilin-binding proteins are indispensable [8] [17]. Future directions will likely focus on engineering brighter near-infrared variants, developing more sensitive biosensors based on environmental sensitivity of these proteins, and creating new systems with tailored photophysical properties for advanced microscopy techniques such as super-resolution imaging and cryo-electron microscopy.

From Lab to Clinic: Practical Applications and Innovative Uses

Live-cell imaging represents a cornerstone of modern biological research, enabling scientists to visualize the intricate dynamics of proteins and cellular processes in real-time. For decades, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and its spectral variants have served as the workhorse tools in this field, revolutionizing our ability to track protein localization, interaction, and function in living systems. However, GFP possesses inherent limitations that restrict its application across all biological contexts. This guide provides a comprehensive objective comparison between conventional GFP-based systems and emerging bilirubin-binding fluorescent proteins (BBFPs), equipping researchers with the experimental data and methodologies necessary to select the optimal tool for their live-cell imaging investigations, particularly under challenging physiological conditions.

Technical Performance Comparison: GFP vs. BBFPs

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Fluorescent Proteins for Live-Cell Imaging

| Feature/Parameter | GFP (mEGFP) | UnaG (BBFP) | IFP2.0 (BBFP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromophore Formation | Oxygen-dependent maturation [8] [20] | Oxygen-independent bilirubin binding [8] [21] | Oxygen-independent biliverdin binding [8] [21] |

| Excitation/Emission Max (nm) | ~488/~510 [22] | ~495/~510 [8] [23] | Far-red excitation/emission [8] |

| Relative Brightness | Bright (benchmark) | Similar to GFP [8] | Dimmer than GFP or UnaG [8] |

| Ligand Requirement | None | Bilirubin (BR) [8] | Biliverdin (BV) [8] |

| Ligand Permeability | Not Applicable | Cell-permeable [8] | Cell-permeable [8] |

| Anaerobic Function | No [8] [20] | Yes [8] [21] [23] | Yes [8] [21] |

| pKa (Acid Sensitivity) | ~6.0 [20] | Data not fully established | Data not fully established |

| Multicolor Imaging | Excellent with variants (e.g., CFP, YFP) [22] | Yes (Green); Orange ligand available [23] | Yes (Far-red) [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Anaerobic Live-Cell Imaging

The following detailed methodology outlines the implementation of BBFPs for live-cell imaging of anaerobic bacteria, as substantiated by key research.

Protocol: Implementing BBFPs in Gut Commensal Bacteria

1. Bacterial Strain Generation and Culture Conditions

- Strains and Plasmids: Utilize Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) or other genetically tractable anaerobes. Clone UnaG or IFP2.0 coding sequences into appropriate expression vectors [8].

- Anaerobic Growth: Culture bacteria in rich media (e.g., tryptone-yeast extract-glucose) within an anaerobic chamber (e.g., Coy chamber) at 37°C. For experiments, back-dilute cultures into defined minimal media with a relevant carbohydrate source (e.g., 0.05% w/v glucose) [8].

- Ligand Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of bilirubin (br) or biliverdin (bv) in DMSO. Supplement growth media with final concentrations of 25 µM bilirubin for UnaG or 2.5 µM biliverdin for IFP2.0 [8].

2. Live-Cell Anaerobic Imaging

- Sample Preparation: Grow cells to early- to mid-log phase. For imaging, seal cells between coverslips using epoxy resin inside the anaerobic chamber to maintain an oxygen-free environment throughout the imaging process [8].

- Microscopy: Perform imaging at room temperature using standard epifluorescence or confocal microscopes. For UnaG, use GFP filter sets (Ex ~485 nm). For IFP2.0, use far-red filter sets [8].

- Controls: Always include wild-type cells not expressing the BBFP but incubated with the same ligand concentration to account for any background or autofluorescence [8] [23].

Protocol: Validation and Functional Assays

1. Ligand Binding and Specificity

- In Vitro Titration: Purify the BBFP and perform fluorescence titration with increasing concentrations of its ligand (br or bv) to determine the dissociation constant (Kd). For the novel orange UnaG ligand, a Kd of 3 nM was measured [23].

- Competitive Assay: To confirm binding occurs in the native bilirubin pocket, perform a competition assay by adding excess native ligand (e.g., bilirubin) and observe the reduction in fluorescence from the new ligand pair [23].

2. Toxicity and Growth Curves

- Monitor bacterial growth via absorbance at OD600 in the presence and absence of ligands to ensure no adverse effects on cell viability or division. Research has shown that ligands like the benzothiazole-based compound "2" at 2.5 µM do not affect the growth kinetics of B. theta [23].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Chromophore Maturation Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Anaerobic Imaging with BBFPs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Live-Cell Imaging with GFP and BBFPs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Chamber | Creates and maintains oxygen-free environment for culture and imaging. | Essential for culturing obligate anaerobes like Bacteroides spp. and for all anaerobic imaging steps [8]. |

| Bilirubin (BR) | Fluorogenic ligand for UnaG BBFP. | Added to media (e.g., 25 µM) to activate green fluorescence in UnaG-expressing cells [8]. |

| Biliverdin (BV) | Fluorogenic ligand for IFP2.0 and other far-red BBFPs. | Added to media (e.g., 2.5 µM) to activate far-red fluorescence [8]. |

| Benzothiazole Ligand "2" | Synthetic orange-emitting ligand for UnaG. | Used at ~2.5 µM for labeling cells in the 540/570 nm channel for multicolor experiments [23]. |

| Epoxy Sealant | Chemically inert sealing agent for microscopy slides. | Seals samples under anaerobic conditions prior to imaging to prevent oxygen ingress [8]. |

| Custom Donor Vectors | Plasmid constructs for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of fluorescent tags. | For endogenous tagging of low-abundance proteins in human cells (e.g., PER2, CRY1) [24]. |

The choice between GFP and bilirubin-binding fluorescent proteins is not a matter of simple superiority but of application-specific suitability. GFP and its variants remain powerful, robust, and largely unparalleled for standard live-cell imaging in aerobic systems, offering a bright, well-characterized, and convenient platform.

However, for investigations venturing into anaerobic environments—such as the gut microbiome, soil ecosystems, or other hypoxic tissues—BBFPs provide a critical and enabling technology. Their oxygen-independent maturation, cell-permeable fluorogenic ligands, and growing color palette make them the definitive choice for these challenging yet biologically crucial contexts. As research continues to illuminate the complex dynamics of life in all its environments, the availability of diverse and specialized tools like BBFPs will be paramount to driving scientific discovery forward.

The development of genetically encoded biosensors represents one of the most significant advancements in molecular biology, enabling real-time monitoring of cellular processes with high spatial and temporal resolution. While traditional Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and its variants have revolutionized cell biology, a new class of bilirubin-inducible fluorescent proteins (FPs) derived from eels offers distinctive advantages for specific biosensing applications [25]. These unique FPs, belonging to the fatty acid binding protein (FABP) family, utilize endogenous bilirubin as a fluorogen and exhibit oxygen-independent maturation, making them particularly valuable for imaging under hypoxic conditions and for detecting specific metabolites [7] [25]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison between GFP-based and bilirubin-binding FP-based biosensors, examining their molecular mechanisms, performance characteristics, and practical applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Molecular Mechanisms and Fundamental Properties

GFP and Its Variants: Structure-Driven Fluorescence

Green Fluorescent Protein and its engineered variants function through an autocatalytically formed chromophore within a protective β-barrel structure [26]. The GFP chromophore derives from a tripeptide sequence (Ser-Tyr-Gly) that undergoes cyclization, dehydration, and oxidation to form the 4-(p-hydroxybenzylidene)-5-imidazolidinone fluorophore [26]. This maturation process requires molecular oxygen, which can limit applications in anaerobic or hypoxic environments [25]. The extensive engineering of GFP has produced variants spanning the visible spectrum, including blue (BFP), cyan (CFP), and yellow (YFP) fluorescent proteins, enabling multi-color imaging and FRET-based sensing approaches [26].

Bilirubin-Binding FPs: Ligand-Induced Fluorescence

In contrast, bilirubin-binding FPs such as UnaG (from Anguilla japonica) and the recently discovered GymFP (from Gymnothorax zonipectis) belong to the FABP family and remain non-fluorescent in their apo state [6] [7]. Their fluorescence is induced by bilirubin binding—a linear tetrapyrrole produced during heme catabolism [7] [5]. The unique Gly-Pro-Pro (GPP) motif conserved in these fluorescent FABPs serves as a structural element that protects bilirubin from solvent quenching, enabling bright fluorescence [27]. Unlike GFP, the fluorophore formation is instantaneous and oxygen-independent, as the chromophore is pre-formed rather than synthesized de novo [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Fluorescent Protein Classes

| Property | GFP-like Proteins | Bilirubin-Binding FPs |

|---|---|---|

| Chromophore Origin | Autocatalytic from protein sequence | Exogenous bilirubin ligand |

| Maturation Requirement | Oxygen-dependent | Oxygen-independent |

| Maturation Time | Hours | Instantaneous upon bilirubin binding |

| Native Structure | β-can fold | β-barrel (FABP family) |

| Molecular Weight | 25-27 kDa | ~15-16 kDa |

| Key Structural Motif | Ser-Tyr-Gly tripeptide | Gly-Pro-Pro motif |

Diagram 1: Fundamental differences in biosensor mechanisms between GFP-based and bilirubin-binding fluorescent proteins.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Spectral Properties and Brightness Characteristics

Direct comparison of spectroscopic properties reveals distinct advantages for each FP class. UnaG exhibits excitation and emission maxima at approximately 498 nm and 527 nm, respectively, with a quantum efficiency of nearly 50% when bound to bilirubin—comparable to enhanced GFP but with the advantage of instantaneous activation [7] [5]. Recent studies have identified that the holoUnaG complex exists in two distinct fluorescence states (holoUnaG1 and holoUnaG2) with a molecular brightness ratio of 1:3.9, suggesting potential for engineering brighter variants [5]. GymFP from moray eel shows similar spectral characteristics with excitation at 496 nm and emission at 532 nm [6].

The small size of bilirubin-binding FPs (~15 kDa versus 25-27 kDa for GFP-like FPs) provides significant advantages for genetic fusion constructs, reducing the potential for steric interference with target protein function [25]. This compact size is particularly beneficial for viral vector-based gene delivery where genetic payload capacity is limited [19].

Environmental Stability and Sensing Capabilities

Bilirubin-binding FPs demonstrate remarkable stability across various environmental conditions. Engineering studies have shown that UnaG mutants maintain function under physiological detection conditions, with certain point mutations (R112M, R132M) modulating binding affinity and thermal stability [7]. Circular dichroism spectroscopy reveals that bilirubin binding enhances the secondary structure content of UnaG variants, contributing to their stability [7].

For metabolite sensing, UnaG derivatives enable highly specific bilirubin detection with dissociation constants in the nanomolar range, allowing development of clinical assays for bilirubin quantification without the need for sample pretreatment [7] [25]. This specificity has been harnessed for developing biosensors for hepatic function and neurological disorders associated with bilirubin metabolism [7].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison

| Parameter | GFP-based Biosensors | Bilirubin-Binding FP Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Efficiency | ~50% (EGFP) | ~50% (UnaG) |

| Excitation/Emission | 488/509 nm (EGFP) | 498/527 nm (UnaG) |

| Brightness Relative to EGFP | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (UnaG) |

| Bilirubin Detection Limit | Not applicable | Nanomolar range |

| Monomeric State | Engineered monomers available | Native monomer |

| Oxidative Stress Resistance | Limited | Enhanced [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Expression and Purification of Bilirubin-Binding FPs

The following protocol for UnaG expression and purification has been adapted from published methodologies [7] [5]:

- Vector Construction: Clone the UnaG coding sequence into pColdI expression vector with an N-terminal 6xHis tag using BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites.

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into BL21 chemically competent E. coli cells.

- Protein Expression: Grow transformed cells in lysogeny broth with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) at 37°C for 3 hours, then induce with 0.5 mM IPTG and continue growth at 16°C for 18 hours.

- Cell Harvesting: Collect cells by centrifugation, wash with potassium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.5), and store cell pellets at -80°C.

- Protein Purification: Thaw cells and homogenize by sonication in potassium phosphate buffer. Apply soluble fraction to HisTrap HP column, wash with buffer containing 20 mM imidazole, and elute with elution buffer containing 500 mM imidazole.

- Buffer Exchange: Desalt eluted protein using PD-10 column with potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.02% sodium azide.

For bilirubin-binding assays, prepare a 1 mM bilirubin stock solution in DMSO and store at -20°C protected from light [5].

Bilirubin Binding and Fluorescence Characterization

- Sample Preparation: Mix purified apoprotein with increasing concentrations of bilirubin (0-500 nM) in potassium phosphate buffer.

- Spectroscopic Analysis:

- Record UV-VIS absorption spectra from 300-600 nm to detect characteristic bilirubin absorption peaks upon binding.

- Measure fluorescence excitation and emission spectra using a fluorescence spectrophotometer.

- For kinetic studies, monitor fluorescence intensity at 527 nm following excitation at 498 nm over time.

- Determination of Binding Affinity:

- Plot fluorescence intensity versus bilirubin concentration.

- Fit data to a hyperbolic binding equation to determine dissociation constant (Kd).

- Alternatively, use nonlinear regression analysis for more complex binding models accounting for the two fluorescence states [5].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for developing bilirubin-binding FP biosensors.

Biosensor Engineering and Applications

Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Protein engineering approaches have significantly advanced both GFP-based and bilirubin-binding FP biosensors. For UnaG, site-directed mutagenesis has targeted key residues involved in bilirubin binding [7]. Replacing arginine residues at positions 112 and 132 with methionine reduces polarity at bilirubin-binding sites, altering spectroscopic properties and binding affinity [7]. The development of eUnaG through valine substitution at position 2 demonstrates approximately twofold enhanced fluorescence intensity compared to wild-type UnaG [7].

Structural studies have been instrumental in these engineering efforts. The conserved Gly-Pro-Pro motif in fluorescent FABPs serves as a critical structural element, with mutation to Gly-Gly-Gly significantly reducing quantum yield and deletion fully quenching fluorescence [6] [27]. Residues adjacent to this motif show evidence of positive selection, suggesting ongoing refinement of fluorescent properties in natural systems [27].

Applications in Metabolic Monitoring and Disease Research

Bilirubin-binding FPs have enabled innovative applications in biomedical research:

- Hypoxia Imaging: The oxygen-independent fluorescence of UnaG has been exploited to visualize hypoxic regions in tumors at cellular resolution, overcoming a significant limitation of GFP-based sensors [25].

- Bilirubin Distribution Mapping: UnaG serves as a fluorescent probe for intracellular bilirubin distribution, providing insights into heme catabolism and bilirubin-related pathologies [5] [25].

- Protein-Protein Interaction Studies: Split UnaG systems (uPPI) enable bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays for monitoring protein interactions in living cells [25].

- Dual-Ligand Sensors: Engineering UnaG with calmodulin creates a dual-ligand modulable fluorescent protein that responds to both bilirubin and calcium concentrations, demonstrating the modularity of these biosensors [25].

- Oxidative Stress Resistance: Cells expressing eel fluorescent protein show approximately twofold greater resistance to oxidative stress like H₂O₂ exposure, suggesting protective functions [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pColdI, pGEX, pTolT | Recombinant protein expression in E. coli |

| Chromophore Ligands | Bilirubin (BR), Unconjugated Bilirubin | Fluorogen for bilirubin-binding FPs |

| Chromatography Media | HisTrap HP, Ni-NTA | Affinity purification of tagged proteins |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Phusion, KOD-Plus-Mutagenesis | Protein engineering and optimization |

| Spectroscopic Equipment | Fluorescence spectrophotometers, CD spectroscopy | Characterization of optical properties |

| Cell Culture Reagents | HEK293 cell line, hypoxic chambers | Cellular biosensor validation |

The expanding toolbox of genetically encoded biosensors continues to transform our ability to monitor cellular metabolism and signaling events. While GFP-based biosensors offer a well-established platform with diverse spectral variants, bilirubin-binding FPs provide unique advantages for specific applications, particularly oxygen-independent imaging, metabolite sensing, and hypoxic environment monitoring. The small size, native monomeric state, and instantaneous activation of bilirubin-binding FPs make them valuable complements to traditional GFP systems.

Future developments will likely focus on engineering enhanced variants with improved brightness and photostability, expanding the color palette through structural modifications, and developing multi-analyte sensors that simultaneously monitor multiple metabolic parameters. The continued discovery and characterization of new bilirubin-binding FPs from diverse eel species [6] [27] promises to provide additional templates for biosensor engineering. As these technologies mature, they will undoubtedly yield increasingly sophisticated tools for fundamental research and drug development, enhancing our understanding of cellular metabolism in health and disease.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) have revolutionized live-cell imaging, transforming our ability to visualize dynamic processes within living systems. As microscopy technologies, particularly super-resolution techniques, advance toward capturing finer structural details at faster speeds, the demand has intensified for FPs with optimized properties. This guide focuses on two distinct families of fluorescent probes: the traditional Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and its variants, and the emerging class of bilirubin-inducible fluorescent proteins (FPs). While GFP-like proteins dominate many biological imaging applications, bilirubin-binding FPs like UnaG and its homologs offer unique advantages for specialized imaging contexts, including oxygen-independent maturation and operation in hypoxic environments [29] [5] [19]. The choice between these protein families significantly impacts experimental outcomes in super-resolution and multiparameter imaging, influencing factors from image brightness to temporal resolution and viability in sensitive cellular conditions. This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal probes for their specific imaging challenges.

Technology Comparison: GFP-vs Bilirubin-Binding FPs

Core Mechanisms and Structures

GFP and its Variants: GFP-like proteins feature a beta-barrel structure that encapsulates a chromophore formed via autocatalytic post-translational modification of three internal amino acids. This maturation process requires molecular oxygen, which can limit their use in anaerobic or hypoxic conditions [16] [19]. Engineering efforts have produced enhanced variants like sfGFP (superfolder GFP) and the recently developed YuzuFP, which demonstrates improved brightness and photostability through a single H148S mutation that enhances chromophore interaction [16].

Bilirubin-Binding FPs (UnaG Family): This class belongs to the fatty acid-binding protein family and features a beta-barrel structure that binds bilirubin (BR) as an exogenous chromophore [5] [6]. Unlike GFP, fluorescence is instantaneous and oxygen-independent, as the chromophore does not require oxidative maturation [5]. The UnaG-BR complex exists in two distinct fluorescence states (holoUnaG1 and holoUnaG2) with a reversible transition between them, offering unique photophysical properties [5].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Representative Fluorescent Proteins

| Protein | Class | Excitation (nm) | Emission (nm) | Quantum Yield | Brightness (Relative) | Maturation | Oxygen Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sfGFP [16] | GFP variant | 485 | 510 | ~0.65 | 1.0 (reference) | Hours | Yes |

| YuzuFP [16] | GFP variant (H148S) | ~485 | ~510 | Higher than sfGFP | 1.5x sfGFP | Hours | Yes |

| UnaG [5] | Bilirubin-binding | 496 | 527 | ~0.50 | Comparable to EGFP | Instantaneous | No |

| HoloUnaG2 [5] | Bilirubin-binding | ~496 | ~527 | - | 3.9x HoloUnaG1 | Instantaneous | No |

| miniGFP1/2 [19] | Flavin-binding | 450 | 499 | - | >2x parental | Instantaneous | No |

Table 2: Photostability and Advanced Application Performance

| Protein | Class | Photobleaching Resistance | Monomeric | Unique Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YuzuFP [16] | GFP variant | ~3x sfGFP | Yes | General super-resolution imaging | Enhanced brightness & stability |

| UnaG [5] | Bilirubin-binding | Moderate | Yes [5] | Hypoxic imaging, BR quantification | Oxygen-independent, no maturation delay |

| miniGFP1/2 [19] | Flavin-binding | Improved vs other FbFPs | Yes | Anaerobic imaging, metal sensing | Small size, Cu(II) sensitivity (Kd ~67 nM) |

Distinct Operational Advantages

GFP Variants excel in general-purpose applications where oxygen is available and maturation time is not critical. Their extensive optimization history provides researchers with a wide range of well-characterized tools for most standard imaging scenarios [16].

Bilirubin-Binding FPs offer crucial advantages for specialized imaging contexts: Their oxygen-independent fluorescence enables imaging in hypoxic environments and anaerobic organisms [19]. Instantaneous fluorogen activation allows real-time observation of rapid biological processes without maturation delays [5]. They also function as biosensors for bilirubin, with applications in quantifying heme catabolism in neurological research [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Characterizing Bilirubin-Binding FP Dynamics

The discovery of two distinct fluorescence states in UnaG required sophisticated biophysical characterization [5]:

Protein Purification: Recombinant 6×His-tagged UnaG was expressed in E. coli and purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) with Ni-NTA resin, followed by desalting into potassium phosphate buffer [5].

Complex Formation: UnaG was mixed with bilirubin (dissolved in DMSO) at specific molar ratios to form the holoUnaG complex [5].

Spectroscopic Analysis: Fluorescence spectra and time-course measurements were performed using a spectrophotometer (RF-5300PC). The team employed photon number counting analysis to quantify the molecular brightness ratio and equilibrium population ratio between holoUnaG1 and holoUnaG2 states [5].

Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC): Both sedimentation velocity (AUC-SV) and sedimentation equilibrium (AUC-SE) analyses were conducted to determine the oligomeric state of apoUnaG and holoUnaG under various conditions [5].

Experimental Workflow for UnaG State Characterization

Protocol 2: Engineering Enhanced GFP Variants

The development of YuzuFP from sfGFP employed computational and molecular biology techniques [16]:

Molecular Dynamics Modeling: Short time-scale (10 ns) MD simulations sampled all 19 canonical amino acids at position H148 to predict changes in chromophore interaction networks and solvation [16].

Mutant Construction: Selected mutations (H148S, H148A, H148C, H148N, H148T) were introduced into sfGFP using site-directed mutagenesis [16].

Spectral Characterization: Absorbance and fluorescence spectra of purified mutants were measured to determine excitation/emission maxima and relative brightness [16].

Photostability Assessment: Proteins were subjected to continuous illumination while monitoring fluorescence decay to quantify resistance to photobleaching [16].

Live-Cell Validation: Selected promising variants were expressed in mammalian cells for imaging under realistic conditions to confirm improved performance [16].

Advanced Microscopy Integration

Super-Resolution Imaging with 3D-MP-SIM

Recent advances in structured illumination microscopy (SIM) have created new demands and opportunities for fluorescent proteins. The development of 3D multiplane SIM (3D-MP-SIM) achieves approximately eightfold increased temporal resolution for volumetric super-resolution imaging, with lateral and axial resolutions of approximately 120 nm and 300 nm, respectively [31]. This technology enables high-speed time-lapse volumetric imaging at rates up to 11 volumes per second, ideal for capturing dynamic processes in live cells [31].

For such applications, the photostability of FPs becomes critically important. YuzuFP's 3-fold increased resistance to photobleaching compared to sfGFP makes it particularly valuable for extended super-resolution time-lapse experiments [16]. Similarly, the oxygen-independent fluorescence of bilirubin-binding FPs provides advantages when imaging hypoxic cellular regions or anaerobic organisms at high resolution [19].

Super-Resolution Microscopy Evolution

Multiparameter Imaging Applications

The distinct spectral and functional properties of different FP classes enable sophisticated multiparameter imaging experiments:

Dual-Color Organelle Interaction Studies: 3D-MP-SIM has demonstrated feasibility for dual-color imaging, enabling observation of rapid interactions between intracellular organelles in 3D space [31]. This requires FPs with precspectral separation and minimal cross-talk.

Metabolic and Ionic Sensing: Flavin-binding miniGFPs demonstrate sensitivity to copper ions (Kd ~67 nM for Cu(II)) and the ability to bind flavin mononucleotide, functioning as multisensing platforms for various analytes [19].

Neurological Biomarker Quantification: The HUG (HELP-UnaG) assay enables nanomolar-range detection of bilirubin and biliverdin in cerebrospinal fluid, providing insights into brain heme catabolism relevant to neurodegenerative diseases [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Fluorescent Protein Research and Applications

| Reagent/Method | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| HUG Assay System [30] | Quantify bilirubin/biliverdin at nM concentrations | Measurement of heme catabolism biomarkers in CSF |

| Analytical Ultracentrifugation [5] | Determine oligomeric state and molecular mass | Verification of UnaG monomeric state |

| Photon Counting Analysis [5] | Quantify molecular brightness ratios | Distinguishing holoUnaG1 vs holoUnaG2 states |

| 3D-MP-SIM Microscopy [31] | High-speed volumetric super-resolution imaging | Capturing ER dynamics at 11 volumes/second |

| Directed Molecular Evolution [19] | Protein engineering through iterative screening | Development of miniGFP1/2 from phiLOV3 template |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations [16] | Predict chromophore-residue interactions | Guiding H148S mutation in YuzuFP development |

The comparative analysis of GFP-like proteins versus bilirubin-binding fluorescent proteins reveals a complementary relationship rather than a competitive one in advanced microscopy applications. GFP variants like YuzuFP currently dominate general super-resolution imaging where their enhanced brightness and photostability provide practical advantages [16]. Meanwhile, bilirubin-binding proteins offer specialized capabilities for hypoxic imaging, anaerobic studies, and metabolic sensing [5] [30] [19].

Future developments will likely focus on engineering bridges between these protein families, creating variants that combine the beneficial properties of each. The successful engineering of YuzuFP through molecular dynamics-guided single mutation demonstrates the potential for rational design to enhance FP performance [16]. Similarly, the discovery of distinct fluorescence states in UnaG opens possibilities for developing brighter mutants constitutively stabilized in the holoUnaG2 state [5].

As microscopy technologies continue advancing toward faster volumetric imaging and higher resolution [31], both protein families will evolve to meet these demands. The ideal FP of the future may combine the oxygen-independent maturation of bilirubin-binding proteins with the exceptional brightness and photostability of optimized GFP variants, potentially through novel engineering approaches or the discovery of entirely new FP classes from unexplored biological sources [6].

The development of cell and gene therapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and viral gene transfer vectors, represents a breakthrough in treating life-threatening diseases. However, the clinical translation of these advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) remains hampered by limited knowledge about their biodistribution, persistence, and dynamic behavior in living organisms. Technologies to non-invasively and quantitatively monitor the distribution of ATMPs in vivo could greatly improve our understanding of their trafficking, therapeutic efficacy, and off-target toxicity. Likewise, adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based gene therapies would benefit from quantifying the location, magnitude, and duration of transgene expression. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current technologies for tracking therapeutic cells and viral vectors in vivo, with particular emphasis on fluorescent protein applications within a broader comparison framework of GFP versus alternative imaging modalities.

Comparative Analysis of In Vivo Tracking Technologies

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of major technologies used for tracking therapeutic cells and viral vectors in vivo.

Table 1: Comparison of Major In Vivo Tracking Technologies

| Technology | Spatial Resolution | Detection Sensitivity | Temporal Tracking Capacity | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET with Reporter Genes [32] | 1-2 mm (preclinical) | ~1,200 CAR T cells [32] | Longitudinal (≥4 weeks) [32] | Whole-body, quantitative, depth-independent, high sensitivity [32] | Requires reporter introduction, radiation exposure, complex radiochemistry |

| Super-resolution Microscopy (dSTORM) [33] | Single-molecule (~20 nm) [33] | Single CAR detection [33] | Terminal (ex vivo) | Tag-free CAR detection, single-molecule sensitivity, quantifies CAR density [33] | No in vivo capability, requires specialized equipment and expertise |