Hyperspectral Imaging for Biofluorescence Characterization: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative role of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) in biofluorescence characterization for biomedical research and drug development.

Hyperspectral Imaging for Biofluorescence Characterization: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) in biofluorescence characterization for biomedical research and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of HSI, which captures both spatial and spectral information to create a detailed chemical fingerprint of samples. The scope extends to methodological advances, including excitation-scanning HSI to overcome signal strength limitations in fluorescence microscopy and the application of algorithms like linear unmixing for sensitive cellular signal detection. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, such as managing variable illumination in surgical settings and optimizing preprocessing pipelines for deep learning. Finally, the article provides a rigorous validation of HSI against established techniques like fluorescence angiography in clinical perfusion assessment and surgical microscopy for glioma detection, demonstrating its superior sensitivity and quantification capabilities. This comprehensive resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement and optimize HSI in their work.

Unlocking Spectral Fingerprints: Core Principles and Advantages of Hyperspectral Biofluorescence Imaging

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is an advanced optical sensing technique that integrates the principles of spectroscopy and digital photography into a single system [1]. This integration enables the simultaneous acquisition of spatial and spectral data, capturing images of a scene across numerous contiguous spectral bands. The result is a three-dimensional dataset known as a hyperspectral data cube, which combines two spatial dimensions (x, y) with one spectral dimension (λ) [1]. Each pixel within this cube contains a continuous spectrum, often referred to as a spectral "fingerprint," that enables precise identification and characterization of materials based on their chemical composition [1].

The fundamental advantage of HSI over conventional imaging modalities lies in its exceptional spectral resolution. While standard RGB cameras capture only three broad spectral bands (red, green, and blue), and multispectral systems typically capture fewer than 20 discrete bands, hyperspectral imaging routinely captures over hundreds of spectral channels at high spectral resolution (commonly 5-10 nm) [1]. This extensive spectral coverage allows researchers to identify subtle yet diagnostically significant features, including molecular absorption bands and pigment-related transitions, which are often invisible or indistinct in conventional imaging [1].

In the context of biofluorescence characterization, HSI has demonstrated particular value due to its inherently non-destructive and label-free nature [1]. Unlike invasive biochemical assays or staining-based microscopy, HSI does not require physical contact or chemical labeling of samples, making it highly suitable for in situ and in vivo applications, continuous monitoring, and real-time diagnostics [2]. This Primer explores the underlying principles, methodological considerations, and practical applications of HSI, with emphasis on its growing role in biomedicine and drug development research.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Implementation

Physical Basis of Hyperspectral Imaging

The high-dimensional nature of hyperspectral data stems from fundamental physical interactions between incident radiation and target materials. When light interacts with matter, several processes occur including electronic transitions, molecular vibrations, scattering, and fluorescence [1]. These interactions, which vary according to the imaging modality and spectral domain, underpin the unique capability of HSI to provide non-destructive, label-free analyses of biological and material samples [1].

Hyperspectral imaging focuses primarily on the optical window of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically covering wavelengths from 380 to 2500 nm [1]. This range encompasses the visible light (400-700 nm), near-infrared (NIR), and short-wave infrared (SWIR) regions. The inclusion of the NIR region (800-2500 nm) is particularly valuable for biofluorescence applications as it corresponds to overtone and combinational vibrational modes of molecular bonds such as O─H, N─H, and C─H [2]. Furthermore, the NIR region offers significant benefits for biomedical applications due to the existence of "optical windows" from 650 to 1350 nm and above 1450 nm, where absorption and scattering are reduced, allowing light to penetrate deeper into biological tissues [2].

Hyperspectral Data Cube Structure and Acquisition

The primary data structure in HSI is the three-dimensional hyperspectral cube, which contains both spatial and spectral information [2]. As illustrated in Figure 1, this cube is formed by stacking images captured across contiguous wavelength bands, assigning a complete spectrum to each spatial pixel [2].

Figure 1. Hyperspectral data cube structure. The cube combines two spatial dimensions with one spectral dimension, capturing a complete spectrum for each pixel.

Two primary approaches exist for hyperspectral data acquisition in fluorescence microscopy: emission-scanning and excitation-scanning HSI [3]. Each method offers distinct advantages and trade-offs for biofluorescence characterization, as summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1: Comparison of HSI Acquisition Modalities for Fluorescence Imaging

| Parameter | Emission-Scanning HSI | Excitation-Scanning HSI |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Separation Method | Filters emission light across bands | Scans excitation wavelength |

| Excitation Source | Broad-band with band-pass filter | Tunable narrow-band illumination |

| Eission Detection | Broad-band or long-pass filter | Tunable filter or dispersive element |

| Signal Strength | Lower (signal divided across bands) | Higher (minimal emission filtering) |

| Photobleaching Risk | Higher | Lower |

| Best Suited For | Bright samples, fixed cells | Live-cell imaging, weak signals |

| Spectral Information | Emission spectrum | Excitation spectrum |

Figure 2. HSI acquisition modalities for fluorescence microscopy. Comparison of emission-scanning and excitation-scanning approaches for hyperspectral imaging.

For dynamic cell signaling studies, excitation-scanning HSI provides significant advantages due to its higher signal strength [3]. This approach utilizes the wavelength-dependent properties of the excitation spectrum of each fluorophore to perform spectral separation, while minimally processing the emission in the spectral dimension, resulting in stronger signals reaching the detector [3]. This enables increased imaging speeds and decreased photobleaching, crucial factors for live-cell imaging and kinetic studies [3].

Experimental Protocols for Biofluorescence Characterization

This protocol describes the implementation of excitation-scanning HSI for kinetic measurements of intracellular Ca²⁺ signals in human airway smooth muscle cells (HASMCs), based on the methodology reported by PMC [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Excitation-Scanning HSI

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function | Supplier Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Airway Smooth Muscle Cells | Primary culture, passages 3-8 | Model system for Ca²⁺ signaling studies | N/A |

| Cal 520-AM | 5 µM in DMSO | Fluorescent Ca²⁺ indicator | AAT Bioquest |

| NucBlue Live ReadyProbes | 2 drops/mL | Nuclear counterstain | ThermoFisher Scientific |

| Laminin-coated Coverslips | 20 mm round | Cell adhesion substrate | Various |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium | With 5% FBS and growth factors | Cell culture maintenance | GIBCO |

| Extracellular Buffer | 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM CaCl₂ | Physiological imaging solution | N/A |

| Excitation-Scanning HSI Microscope | Tunable excitation source, broad-band emission filter | Hyperspectral image acquisition | Custom or commercial |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Cell Culture and Preparation

- Culture HASMCs in Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, basic fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at pH 7.0 [3].

- Seed cells onto 20 mm laminin-coated round glass coverslips and incubate at 37°C and 5% CO₂ for 48 hours or until 70-80% confluency [3].

Fluorescent Labeling

- Prepare single-label control samples for system validation:

- For experimental samples: Prepare mixed-label samples using both Cal 520-AM and NucBlue labeling with identical concentrations and incubation times as single-label controls [3].

Hyperspectral Image Acquisition

- Transfer labeled coverslips to an appropriate imaging chamber (e.g., attoflour holder) covered with extracellular buffer [3].

- Configure excitation-scanning HSI system parameters:

- Set excitation wavelength range to cover absorption peaks of all fluorophores (typically 350-500 nm for Cal 520 and DAPI-channel dyes).

- Set emission detection using a broad-band or long-pass emission filter.

- Define spectral sampling interval (typically 5-10 nm) and exposure time per wavelength.

- Acquire time-lapse excitation-scanning HSI data with appropriate temporal resolution for the kinetic process being studied (e.g., 30-second intervals for Ca²⁺ oscillations).

Spectral Data Analysis

- Process raw HSI data using one of the following algorithms:

- Linear Unmixing (LU): Separates signals based on reference spectra [3].

- Constrained Energy Minimization (CEM): Minimizes energy from background while maintaining target response [3].

- Matched Filter (MF): Enhances response of target spectrum while suppressing background [3].

- Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM): Compares angles between spectral vectors [3].

- Apply theoretical sensitivity framework to filter pixels below minimum detectable limit.

- Extract quantitative Ca²⁺ signal traces from regions of interest.

- Process raw HSI data using one of the following algorithms:

Protocol 2: HyperNIR Spectral Phasor Imaging for Biofluorescence

This protocol describes the implementation of a fast NIR hyperspectral imaging approach using spectral phasor transformation (HyperNIR) for distinguishing NIR fluorophores with emission peaks less than 5 nm apart [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HyperNIR Imaging

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Fluorophores | Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) or other NIR fluorophores | Biofluorescence labels | Tailorable as biosensors |

| Liquid Crystal Variable Retarder | Electrically tunable retardance | Spectral filtering element | Core component of HyperNIR |

| Linear Polarizers | High extinction ratio, NIR compatible | Polarization control | Two units required |

| NIR-Sensitive Camera | InGaAs detector or similar | NIR light detection | Typically 0.1 MP resolution |

| Optical Mounting Hardware | Cage system or custom mount | System alignment | Precision positioning required |

Step-by-Step Procedure

HyperNIR System Configuration

- Assemble optical module with two parallel linear polarizers (set at 45° with respect to the fast axis of the variable retarder) and a liquid crystal variable retarder (LCVR) placed between them [2].

- Align optical components to ensure collimated light path through the entire system.

- Connect LCVR to appropriate control electronics for rapid retardance adjustment.

Spectral Calibration

- Characterize the wavelength-dependent transmission of the system using known light sources.

- Determine the relationship between applied voltage to the LCVR and resulting retardance.

- Tune the retardance to cover the desired spectral range (900-1600 nm, adjustable in windows from 50 to 700 nm) [2].

- Optimize system for specific spectral region of interest by minimizing phasor calculation error.

Image Acquisition

- For each sample, acquire three key images:

- Cosine-filtered image: Set LCVR to create cosine-shaped spectral transmission.

- Sine-filtered image: Adjust LCVR to sine-shaped spectral transmission.

- Normalization image: Set retardance to zero for wavelength-independent transmission [2].

- Maintain consistent illumination and exposure settings across all three acquisitions.

- For each sample, acquire three key images:

Spectral Phasor Analysis

- Transform optical signals into 2D spectral phasor space using the acquired sine, cosine, and normalization images.

- Map each pixel into phasor space where position contains spectral information.

- Identify and separate distinct fluorophores based on their clustering in phasor space.

- Apply phasor analysis to distinguish fluorophores with emission peaks separated by less than 5 nm [2].

Data Processing and Analysis Methods

Preprocessing Strategies for Hyperspectral Data

Effective preprocessing of hyperspectral data is essential for optimal analysis results, particularly in biomedical applications. A recent comprehensive study compared various preprocessing techniques for hyperspectral deep learning-based cancer diagnostics, with findings relevant to biofluorescence characterization [4].

Table 4: Comparison of HSI Preprocessing Techniques for Biomedical Applications

| Preprocessing Step | Options | Performance Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaling | Normalization, Standardization | Standardization significantly improves both sensitivity and specificity compared to Normalization [4] | Use Z-score standardization for enhanced convergence |

| Spatial Context | Patch size 3, Patch size 5 | Larger input patch sizes enhance performance by capturing more spatial context [4] | Use larger patches (e.g., 5×5) when computational resources allow |

| Noise Reduction | 1D, 2D, 3D smoothing with Median, Gaussian, or Savitsky-Golay filters | Noise reduction unexpectedly degrades performance [4] | Apply smoothing cautiously; validate performance impact |

| Artifact Filtering | Blood filtering, Light reflection filtering | Blood filtering is more effective than filtering reflected light pixels [4] | Prioritize blood absorption artifact removal |

| Dataset Imbalance | Class weighting, Sample weighting | Addresses underrepresentation of target features [4] | Implement weighting strategies for imbalanced datasets |

Spectral Analysis Algorithms

For quantitative analysis of hyperspectral biofluorescence data, several algorithms have been compared for their effectiveness in dynamic cell signaling studies [3]:

Linear Unmixing (LU): Separates mixed fluorescence signals based on reference spectra of pure fluorophores. Demonstrates linear response to increasing Ca²⁺ concentrations and effective signal separation from autofluorescence [3].

Constrained Energy Minimization (CEM): Minimizes energy from background components while maintaining a strong response to the target signature. Effective for detecting weak signals in high-background environments [3].

Matched Filter (MF): Enhances the response of a target spectrum while suppressing the background. Shows similar linear response to LU for quantitative Ca²⁺ measurements [3].

Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM): Compares the angles between spectral vectors rather than their magnitudes. Less sensitive to illumination variations but may be less effective for quantitative measurements [3].

The selection of an appropriate algorithm should be guided by the specific application requirements, with LU and MF recommended for quantitative kinetic studies based on their demonstrated linear response to increasing analyte concentrations [3].

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Hyperspectral imaging has shown significant potential across various domains of biomedical research and drug development. In cancer diagnostics, HSI has been applied for discrimination of pathological tissues in colorectal cancer [4], skin cancer [4], breast cancer [4], head and neck cancer [4], brain cancer [4], oral cancer [4], and gastric cancer [4]. The technology enables non-invasive, label-free identification of cancerous tissues based on their spectral characteristics, providing valuable intraoperative guidance and margin assessment [4].

In drug development, HSI facilitates high-content screening and mechanistic studies of drug effects through several approaches:

- Receptor Trafficking Studies: Monitoring of GPCR internalization and recycling using labeled ligands or fluorescent protein tags.

- Second Messenger Assays: Quantitative measurement of intracellular Ca²⁺, cAMP, IP₃, and other signaling molecules.

- Metabolic Activity Profiling: Label-free assessment of cellular metabolism through autofluorescence imaging of NADH, FAD, and other intrinsic fluorophores.

- Cytotoxicity and Viability Screening: Multiparametric assessment of drug effects using multiple fluorescent indicators simultaneously.

The non-destructive nature of HSI makes it particularly valuable for longitudinal studies where the same cells or tissues need to be monitored over extended periods, such as in time-course experiments of drug response or stem cell differentiation.

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of hyperspectral imaging for biofluorescence characterization is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends shaping its future development:

AI-Driven Analysis: Deep learning approaches, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are transforming HSI data processing by enabling automatic extraction of nonlinear spectral features without manual preprocessing [5]. Lightweight CNN architectures are being developed for resource-constrained applications, facilitating real-time analysis onboard satellite platforms or portable devices [5].

Miniaturization and Portability: Advances in optics and detector technologies are driving the development of compact, portable HSI systems suitable for point-of-care diagnostics and field applications [1].

High-Speed Acquisition: New approaches such as the HyperNIR spectral phasor method are addressing the intrinsic speed limitations of traditional HSI, enabling hyperspectral frame rates of 0.2 s⁻¹ [2].

Cross-Modal Fusion: Integration of HSI with other imaging modalities (e.g., MRI, CT, photoacoustic imaging) provides complementary information and enhances diagnostic capability.

Foundation Models: Development of large-scale pretrained models for HSI analysis promises to improve generalizability across tasks, domains, and sensor types [1].

As these trends continue, hyperspectral imaging is poised to become an increasingly accessible and powerful tool for biofluorescence characterization in basic research, drug development, and clinical applications.

Biofluorescence hyperspectral imaging (HSI) represents a transformative approach in analytical science, enabling non-destructive, label-free chemical characterization across diverse research domains. This technique captures both spatial and spectral information from autofluorescent samples or those labeled with exogenous fluorophores, providing a comprehensive molecular fingerprint without the need for destructive sample preparation. The integration of advanced chemometric algorithms and computational imaging approaches has significantly enhanced our ability to extract meaningful chemical information from complex biological and material systems. This application note details the fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and key applications of hyperspectral biofluorescence imaging, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementation in pharmaceutical development, biomedical research, and agricultural science.

Hyperspectral biofluorescence imaging merges the molecular specificity of fluorescence spectroscopy with spatial mapping capabilities, creating a powerful tool for non-destructive material characterization. Unlike conventional fluorescence microscopy that relies on measurements at single excitation and emission bands, HSI acquires the complete emission spectrum at each spatial location within a sample, generating a three-dimensional dataset (x, y, λ) often called a "hypercube" [6]. This comprehensive spectral data enables researchers to distinguish between multiple fluorescent signals even when they significantly overlap, providing unprecedented capability for analyzing complex chemical compositions without damaging samples [7].

The "biofluorescence advantage" stems from several key benefits: non-destructive operation that preserves sample integrity, label-free detection that leverages intrinsic fluorescent properties, high molecular specificity through unique spectral signatures, and exceptional sensitivity capable of detecting fluorescent signals as low as 15% of the autofluorescence intensity in highly autofluorescent tissues [6]. These characteristics make the technology particularly valuable for applications where sample preservation is critical, such as forensic evidence analysis [8], pharmaceutical tablet characterization [9], and longitudinal biological studies [7].

Key Applications and Performance Metrics

Application Domains

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Hyperspectral Biofluorescence Imaging

| Application Domain | Specific Use Cases | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Analysis | Characterization of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in tablets [9] | Non-destructive quality control; rapid in-line analysis |

| Forensic Science | Identification of bio-fluids (blood, urine, saliva, sperm) on cotton supports [8] | Non-destructive evidence preservation; minimal sample preparation |

| Biomedical Research | Detection of GFP-expressing cells in highly autofluorescent lung tissue [6] | High sensitivity in challenging environments; accurate cell quantification |

| Agricultural Science | Chlorophyll content monitoring in rice leaves [10] | Non-destructive plant health assessment; precision agriculture enablement |

| Food Safety | Prediction of microbial growth in chicken breasts [11] | Rapid contamination assessment; non-invasive quality monitoring |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Hyperspectral Biofluorescence Imaging Across Applications

| Application | Detection Sensitivity | Accuracy/Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFP Detection in Lung Tissue | GFP intensity as low as 15% of autofluorescence | Zero false positives detected; substantially better than single-band thresholding [6] | |

| Chlorophyll Detection in Rice | N/A | RMSE-Train: 0.26, RMSE-Test: 0.29, RPD: 2.64 (CNN+LSTM model with fluorescence data) [10] | |

| Bio-fluid Identification | N/A | Successful discrimination of blood, urine, saliva, and sperm spots on cotton using SIMCA, PCA, and PLS-DA [8] | |

| Pharmaceutical API Characterization | N/A | Complete separation of ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid, and paracetamol using first two principal components [9] |

Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for Hyperspectral Fluorescence Imaging

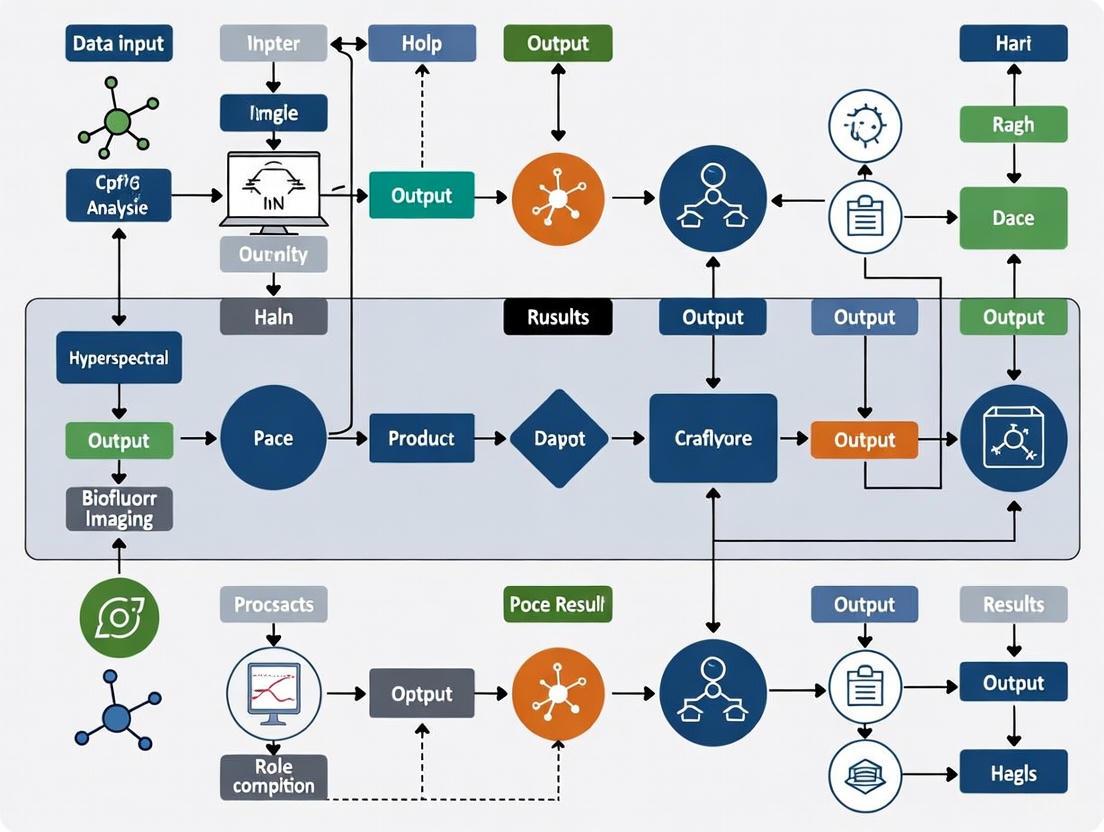

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for hyperspectral fluorescence imaging experiments, from sample preparation through data analysis:

Protocol 1: Detection of Bio-fluids on Forensic Substrates

Application: Identification of blood, urine, saliva, and sperm spots on cotton fabric for forensic analysis [8]

Materials and Reagents:

- White cotton fabric substrates

- Reference bio-fluids (blood, urine, saliva, sperm)

- Raman hyperspectral imaging system

- MATLAB or similar analytical software with chemometric tools

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Deposit controlled volumes (2-10 µL) of bio-fluids onto white cotton fabric

- Allow samples to air-dry under controlled conditions (temperature, humidity)

- Prepare replicate samples for validation

Instrument Configuration:

- Configure Raman hyperspectral imaging system with appropriate laser wavelengths

- Set spatial resolution to capture fiber-level details

- Calibrate instrument using standard reference materials

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire hyperspectral images across appropriate spectral range (e.g., 500-1800 cm⁻¹ Raman shift)

- Ensure sufficient spectral resolution (typically 4-8 cm⁻¹) for molecular discrimination

- Include control samples (pure cotton substrate) in each imaging session

Data Analysis:

- Apply preprocessing: cosmic ray removal, fluorescence background subtraction, vector normalization

- Implement SIMCA for initial pixel classification and detection of bio-fluid regions

- Use PCA to explore spectral variance within and between bio-fluid classes

- Apply PLS-DA to build predictive models for bio-fluid identification

- Validate models using cross-validation and independent test sets

Technical Notes: This methodology enables non-destructive analysis of forensic evidence, preserving samples for subsequent DNA analysis or other confirmatory tests. The approach successfully discriminates between forensically relevant bio-fluids based on their intrinsic molecular signatures without chemical pretreatment [8].

Protocol 2: Detection of GFP-expressing Cells in Autofluorescent Tissues

Application: Identification and quantification of GFP-labeled pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells in highly autofluorescent lung tissue [6] [12]

Materials and Reagents:

- Lung tissue sections (10 μm cryoslices)

- GFP-expressing PMVECs and vector control cells

- Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain (5 μg/mL)

- Fluorescent mounting medium

- Custom hyperspectral imaging fluorescence microscope with AOTF

- MATLAB with custom analysis scripts

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Perfuse GFP+ or vector control PMVECs into pulmonary circulation of CD rats

- Fix perfused lungs in OCT compound

- Prepare 10 μm cryosections using cryostat

- Stain with Hoechst 33342 (0.225 μM) for nuclear visualization

- Mount with fluorescent mounting medium

Instrument Configuration:

- Configure hyperspectral microscope with 40X oil immersion objective

- Set excitation wavelength to 430 nm for GFP imaging

- Set AOTF to acquire emission from 450-700 nm in 5 nm increments

- Use 8.5 nm FWHM bandwidth and 2 second exposure per spectral band

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire hyperspectral image stacks from multiple tissue regions

- Include control samples: GFP+ cell monolayers, vector control tissues, blank slides

- Acquire Hoechst images using 360 nm excitation and 450 nm emission for nuclear reference

Data Analysis:

- Perform background subtraction and flat-field spectral correction

- Extract pure spectra from control samples for spectral library development

- Apply non-negative least squares linear unmixing to resolve GFP signal from autofluorescence

- Validate detection sensitivity using "what-if" scenarios with artificially added GFP signals

- Establish detection thresholds based on histogram analysis of unmixed signal distributions

Technical Notes: This approach enables accurate detection of GFP-expressing cells even when GFP intensity is as little as 15% of the autofluorescence intensity. The method achieves zero false positives compared to standard thresholding approaches, which produce substantial false positives [6].

Protocol 3: Chlorophyll Monitoring in Rice Leaves

Application: Non-destructive assessment of chlorophyll content in rice leaves using hyperspectral and fluorescence imaging [10]

Materials and Reagents:

- Rice leaf samples (Ya5You5217 cultivar)

- GaiaSorter Hyperspectral Sorter or equivalent system

- SPAD device for reference measurements

- MATLAB or Python with machine learning libraries

Procedure:

- Sample Collection:

- Collect rice leaf samples from experimental fields (minimum 90 samples for robust models)

- Include leaves representing various health states and growth stages

- Perform reference chlorophyll measurements using SPAD device or chemical analysis

Spectral Data Acquisition:

- Acquire hyperspectral images using GaiaSorter Hyperspectral Sorter

- Collect fluorescence spectral data using appropriate excitation/emission settings

- Ensure consistent illumination and measurement geometry across samples

Feature Extraction:

- Apply IVSO-IVISSA (Iteratively Variable Subset Optimization–Interval Variable Iterative Space Shrinkage Approach) for feature selection

- Identify characteristic spectral bands correlated with chlorophyll content

- Extract both hyperspectral and fluorescence spectral features

Model Development:

- Implement CNN+LSTM (Convolutional Neural Network + Long Short-Term Memory) architecture

- Train models to predict chlorophyll content from spectral features

- Validate models using cross-validation and independent test sets

- Compare performance with traditional machine learning algorithms (PLS, SVM)

Technical Notes: The combined CNN+LSTM model with fluorescence spectrum data demonstrates superior prediction performance (RMSE-Test: 0.29, RPD: 2.64) compared to hyperspectral data alone, enabling rapid, non-destructive crop health monitoring for precision agriculture applications [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hyperspectral Biofluorescence Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33342 | Nuclear counterstain | Cell nucleus identification in tissue sections [6] [12] |

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Cellular labeling | Tracking and quantification of specific cell populations [6] [12] |

| Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) Compound | Tissue embedding medium | Cryosection preparation for tissue imaging [6] |

| Fluorescent Mounting Medium | Slide mounting | Preservation of fluorescence and reduction of photobleaching [6] |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) | Reflection standard | UV illumination homogenization in pharmaceutical applications [9] |

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) | Target analytes | Pharmaceutical tablet characterization [9] |

Data Processing and Analysis Approaches

Spectral Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the spectral data processing pathway from raw acquisition to final interpretation:

Advanced Analysis Methods

Spectrally Encoded Enhanced Representations (SEER): This approach, based on the phasor method, transforms wavelength space into information-rich color maps for intuitive RGB visualization. SEER enables rapid visualization of subtle spectral differences during data acquisition and pre-processing, significantly enhancing interpretability of complex hyperspectral datasets [7]. The method involves five key steps: (1) Fourier transformation of spectral data, (2) histogram representation of phasor plot, (3) spatially lossless spectral denoising, (4) assignment of RGB colors based on phasor position, and (5) remapping of original dataset colors based on SEER results.

Compressive Fluorescence Microscopy (CFM): This innovative approach implements compressed sensing theory to reduce data acquisition requirements in fluorescence microscopy. By using patterned illumination and computational reconstruction, CFM enables image acquisition with undersampling ratios up to 32 for standard imaging and 64 for hyperspectral imaging, dramatically reducing acquisition time and data storage requirements while maintaining image quality [13].

Hyperspectral biofluorescence imaging represents a powerful paradigm for non-destructive, label-free chemical characterization across diverse scientific domains. The methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust frameworks for implementing these techniques in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to agricultural science and biomedical research. The continuous advancement of computational analysis methods, including machine learning approaches and innovative visualization techniques like SEER, continues to expand the capabilities and applications of this technology.

As hyperspectral imaging systems become more accessible and computational methods more sophisticated, the "biofluorescence advantage" of non-destructive, label-free chemical characterization is poised to become increasingly integral to research and quality control workflows where sample preservation and comprehensive molecular information are paramount.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) has emerged as a transformative tool for biofluorescence characterization, enabling the non-invasive, label-free analysis of biological samples by simultaneously capturing spatial and spectral information. This capability is crucial for advanced research in drug development, where understanding subtle biochemical interactions and cellular responses is paramount. The performance of a hyperspectral system is fundamentally dictated by its core hardware components: the detector camera, the spectral dispersion mechanism, and the illumination sources. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for these key components, framed within the context of configuring a hyperspectral imaging system for biofluorescence research. We summarize critical performance data in structured tables and provide explicit experimental methodologies to guide researchers and scientists in optimizing their systems for high-fidelity, reproducible results.

The Hyperspectral Imaging Pipeline and Component Integration

The process of generating a hyperspectral data cube—a three-dimensional dataset comprising two spatial dimensions and one spectral dimension—relies on a specific sequence of hardware components. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow and the role of each key component.

Core Hardware Components: Specifications and Selection Criteria

Scientific Detectors: sCMOS vs. EMCCD

The detector is a critical element that converts incoming photons into a quantifiable electronic signal. For biofluorescence characterization, where signals can be weak, the choice between sCMOS and EMCCD technology is fundamental [14] [15] [16].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of sCMOS and EMCCD Detectors

| Parameter | sCMOS | EMCCD | Implication for Biofluorescence Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Noise | ~1.0–1.9 electrons (rms) [15] | <1 electron (with EM gain) [15] [16] | EMCCD superior for ultra-low-light, single-photon detection. |

| Quantum Efficiency (QE) | Up to 95% (back-illuminated) [16] | >95% (back-illuminated) [15] | Both high; EMCCD has a slight edge in photon collection. |

| Frame Rate | >100 fps (at full frame) [16] | ~26 fps (1024x1024 sensor) [15] | sCMOS is ideal for high-speed dynamic processes. |

| Dynamic Range | 16-bit, up to 53,000:1 [16] | High, but limited by EM gain noise [15] | sCMOS better for capturing both bright and dim features in one image. |

| Spatial Resolution | Multi-megapixel (e.g., 5.5 MP) [15] | Typically ~1 MP or less [15] [16] | sCMOS provides a larger field of view and finer spatial detail. |

| Multiplicative Noise | None [15] | Present (factor of √2) [15] | sCMOS provides superior signal-to-noise at medium-high light levels. |

| Typical Cost | \$5,000–\$20,000 [16] | \$20,000–\$30,000 [16] | sCMOS is more cost-effective for most non-single-molecule applications. |

Application Note: The decision between sCMOS and EMCCD should be driven by the specific photon flux of the experiment. sCMOS cameras are the preferred choice for the majority of biofluorescence applications due to their excellent balance of speed, resolution, dynamic range, and sensitivity [14] [15]. They are particularly suited for live-cell imaging, spectral imaging, and high-speed kinetics where photon counts are not limiting. EMCCD cameras remain the gold standard for the most demanding low-light applications, such as single-molecule localization microscopy (e.g., STORM, PALM) or tracking low-copy-number biomarkers, where their single-photon sensitivity is critical [15] [16].

Spectral Dispersion Components: Tunable Filters and Gratings

The imaging spectrometer, housing the spectral dispersion element, is the core component that distinguishes HSI from conventional imaging [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Spectral Dispersion Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism | Spectral Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffraction Grating | Wavelength separation via diffraction angles. | High (e.g., 5-10 nm) [1] | High light throughput, mechanical stability, fast spectral acquisition. | Complex data cube reconstruction (scanning). |

| Liquid Crystal Tunable Filter (LCTF) | Electrically controlled birefringence [1]. | Moderate to High | Flexible, random wavelength access, no moving parts. | Lower light throughput compared to gratings. |

| Acousto-Optic Tunable Filter (AOTF) | Radiofrequency-controlled diffraction in a crystal [1]. | High | Very fast wavelength switching (microseconds). | Higher cost, more complex electronics. |

| Prism | Wavelength-dependent refraction [1]. | Moderate (non-linear dispersion) | Robustness and stability. | Non-linear dispersion complicates spectral calibration. |

Application Note: For high-speed, bright-field hyperspectral imaging (e.g., in transmitted light modes), grating-based spectrometers coupled with sCMOS cameras are often optimal due to their high throughput and speed. For fluorescence hyperspectral imaging, where light levels may be lower and out-of-band rejection is critical, LCTFs or AOTFs provide excellent performance by selectively isolating specific emission bands without the need for physical movement [1].

Precise illumination is vital, especially for fluorescence excitation-emission matrix (EEM) approaches, which map fluorescence characteristics across multiple excitation and emission wavelengths [17] [18].

Table 3: Illumination Sources for Biofluorescence HSI

| Source Type | Spectral Range | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tunable LEDs | Discrete wavelengths from UV to NIR. | Long lifetime, stable output, compact, cost-effective. | Ideal for EEM-based systems; allows programmable excitation [18]. |

| Xenon Arc Lamps | Broadband (UV-Vis-NIR). | High intensity, continuous spectrum. | Requires external bandpass filters for specific excitation. |

| Laser Sources | Discrete, high-intensity lines. | Very high power density, monochromatic. | Best for techniques like CARS; requires safety precautions [14]. |

Application Note: The trend in modern HSI system design is toward LED-based illumination due to its stability, longevity, and the ease with which multiple discrete wavelengths can be integrated and controlled electronically. This is particularly suited for building optimized Fluorescence Imaging Systems (FIS) guided by EEM data, as it allows for the precise selection of excitation wavelengths that target specific fluorescent compounds (e.g., chlorophyll, flavonoids, NADH) [18].

Experimental Protocols for System Characterization

Protocol: Detector Performance Validation for Low-Light Fluorescence

This protocol assesses whether a detector (sCMOS or EMCCD) meets the sensitivity requirements for a given biofluorescence application.

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a dilution series of a stable fluorophore (e.g., Fluorescein, Rhodamine) spanning a concentration range expected in your biological samples.

- Spot 1 µL of each dilution onto a clean glass slide and create a sealed preparation.

Image Acquisition:

- Mount the slide on the HSI microscope stage.

- Set the illumination intensity to a low, non-saturating level and keep it constant for all acquisitions.

- For sCMOS: Set the camera to its lowest read noise mode and a 16-bit dynamic range. Acquire images at a fixed exposure time (e.g., 100 ms, 500 ms, 1 s).

- For EMCCD: Start with EM gain at 1 (off) to characterize baseline performance. Then, incrementally increase the EM gain until the signal from the dimmest detectable sample is sufficiently above the background. Record the corresponding EM gain setting.

Data Analysis:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): For each fluorophore spot and each camera setting, measure the mean signal intensity in a Region of Interest (ROI) and the standard deviation of the signal in a background ROI. Calculate SNR as (MeanSignal - MeanBackground) / Std_Background.

- Dynamic Range: Image a sample with both very bright and very dim features. Confirm that the detector can resolve the dimmest feature without noise saturation while the brightest feature is not pixel-saturated.

- Validation Criterion: The detector is suitable if the SNR for the target signal intensity is ≥ 5-10 under the intended experimental acquisition conditions.

Protocol: Spectral Calibration and Illumination Optimization

This protocol ensures accurate wavelength assignment and selects optimal excitation wavelengths for a target fluorophore.

Spectral Calibration:

- Use a calibration lamp with known emission lines (e.g., Mercury-Argon lamp).

- Acquire spectra of the lamp using your HSI system.

- Plot the known peak wavelengths against the corresponding pixel positions on the detector. Fit a polynomial function (linear or quadratic) to create a wavelength-pixel mapping model.

Excitation-Emission Matrix (EEM) Profiling:

- Place a sample of the pure target fluorophore (e.g., a key cellular metabolite) in the system.

- Using a tunable excitation source (e.g., a tunable laser or LED array), systematically step through a range of excitation wavelengths (λ_ex).

- At each λex, acquire the full emission spectrum (λem).

- Construct a 3D EEM plot (Excitation Wavelength vs. Emission Wavelength vs. Fluorescence Intensity) [18].

Illumination Selection:

- Analyze the EEM to identify the peak excitation wavelength (λexmax) for the target fluorophore.

- For multi-fluorophore imaging, analyze the EEMs of all targets to select 2-3 excitation wavelengths that provide the best spectral separation (discriminatory power) between them, minimizing cross-talk [19] [18]. Studies show that transitioning from single to dual illumination significantly enhances performance with diminishing returns beyond two illuminations [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Materials for Hyperspectral Biofluorescence Experiments

| Item | Specification/Example | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Fluorophores | Fluorescein, Rhodamine B, Nile Blue | System calibration, sensitivity validation, and positive controls. |

| Reference Standards | Wavelength calibration lamp (Hg/Ar), Spectralon reflectance tile | Spectral calibration and radiometric correction of the HSI system. |

| Biological Stains | DAPI, Hoechst (nucleus); MitoTracker (mitochondria); FM dyes (membrane) | Labeling specific cellular compartments for spatial-spectral analysis. |

| Metabolic Co-factors | NADH, FAD (autofluorescent) | Label-free monitoring of cellular metabolism and redox state. |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Phenol-red free medium, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), PBS buffer | Maintaining cell health and minimizing background fluorescence during live-cell HSI. |

| Microplates/Slides | Glass-bottom dishes, Black-walled 96-well plates | Sample mounting; black walls reduce cross-well fluorescence. |

The successful implementation of hyperspectral imaging for biofluorescence characterization hinges on a deliberate and informed selection of hardware components. As detailed in these application notes, sCMOS detectors generally offer the best balance of performance for most dynamic, live-cell imaging applications, while EMCCDs remain indispensable for single-photon-counting experiments. The choice of spectral dispersion technology should align with the required speed and light throughput, with tunable filters like LCTFs and AOTFs offering significant flexibility for fluorescence EEM studies. Finally, the move toward programmable, multi-wavelength LED illumination enables the precise excitation control needed to dissect complex biochemical environments. By following the provided protocols for system validation and calibration, researchers in drug development can establish robust, reliable, and highly informative HSI platforms to advance their characterization of biological systems.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is an advanced optical sensing technique that captures both spatial and spectral information from a sample, generating a three-dimensional data cube often referred to as a hyperspectral cube [1]. This cube contains detailed spectral information obtained by measuring reflectance or radiance across finely resolved spectral intervals, enabling precise identification and characterization of materials, biological tissues, and environmental surfaces [1]. Unlike conventional imaging modalities, HSI typically captures hundreds of narrow spectral channels within and beyond the visual spectral range, providing a continuous spectrum for each pixel that allows identification based on chemical composition [20].

Despite its powerful capabilities, traditional HSI faces significant limitations. Conventional methods rely on spatial or spectral scanning, which makes the technique intrinsically slow and limits its application in dynamic biological systems [2] [21]. The near-infrared (NIR) range (800-2500 nm) is particularly advantageous for biomedical and environmental applications because it falls into the tissue transparency window and contains vibrational overtone and combination modes useful for molecular fingerprinting [2]. However, standard HSI approaches struggle to capture rapid biological processes in this spectrum.

The spectral phasor approach transforms this landscape by providing a fit-free, high-speed method for hyperspectral imaging. This approach maps complex spectral information from each pixel into a 2D polar plot (phasor plot), where the angular position represents the center of mass of the emission spectrum, and the distance from the center indicates the spectral width [22] [21]. By performing this transformation directly in hardware using specialized optical filters, the method achieves dramatic improvements in imaging speed while maintaining high spectral resolution [2] [21].

The HyperNIR system implements a tunable phasor-based approach to NIR hyperspectral imaging using polarization optics to generate wavelength-dependent sine- and cosine-filtering [2]. The core optical module consists of two parallel linear polarizers and a liquid crystal variable retarder (LCVR) that transforms optical signals directly into a 2D spectral phasor space with just three images [2].

Optical Configuration and Working Principle

The HyperNIR module features two linear polarizers oriented at 45° with respect to the fast axis of the variable retarder [2]. NIR light from fluorescence, reflected, or transmitted signals first passes through the initial polarizer, which filters the 45° component. The LCVR then imposes a variable retardation, creating an elliptically polarized beam dependent on wavelength. The second polarizer filters the 45° component of this elliptically polarized light, resulting in a wavelength-dependent transmission described by the equation:

[ T(R, \lambda) = \frac{I}{I_0} = \frac{1}{2} \left[ 1 + \cos \left( \frac{2\pi R}{\lambda} \right) \right] ]

where (R) represents the retardance and (\lambda) the wavelength [2]. This configuration generates sine- and cosine-shaped spectral transmissions that can be spectrally shifted by modulating the retardance, enabling the system to cover spectral ranges from 900 to 1600 nm in windows tunable from 50 to 700 nm [2].

Key Advantages Over Conventional HSI

The HyperNIR system addresses several critical limitations of conventional hyperspectral imaging:

- Speed: Achieves hyperspectral frame rates of 0.2 s⁻¹, limited only by the switching rate of the LCVR, compared to much slower scanning approaches [2]

- Spectral Resolution: Can distinguish NIR fluorophores with emission peaks less than 5 nm apart [2]

- Hardware Efficiency: Uses full camera resolution without the spatial compromise of mosaic-pattern or light-field snapshot cameras [2]

- Cost-Effectiveness: Components start at approximately 2000 €, significantly less than custom-built interference filters [2]

- Adaptability: The LCVR can be electronically switched between sine, cosine, and no spectral filtering modes, enabling flexible experimental designs [2]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: HyperNIR System Calibration and Operation

Purpose: To calibrate the HyperNIR system for hyperspectral imaging of samples in the NIR range (900-1600 nm) [2].

Materials:

- HyperNIR system with LCVR module

- NIR-compatible camera (InGaAs recommended)

- Standard NIR fluorophores or reflectance standards

- Computer with control software

Procedure:

System Setup

- Mount the HyperNIR module between the microscope/imager and the NIR camera

- Ensure linear polarizers are oriented at 45° relative to the LCVR fast axis

- Connect LCVR to controller and computer

Spectral Range Calibration

- Set desired spectral window (50-700 nm range within 900-1600 nm)

- Apply voltage sequences to LCVR to achieve sine and cosine filtering modes

- Capture reference images using NIR standards with known spectra

- Verify transmission function matches theoretical expectations

Image Acquisition

- For each sample position, acquire three images:

- Image with sine spectral filtering

- Image with cosine spectral filtering

- Reference image without spectral filtering (retardance set to zero)

- Maintain consistent exposure times across acquisitions

- For each sample position, acquire three images:

Phasor Calculation

- For each pixel, calculate real (G) and imaginary (S) phasor components: [ G = \frac{I{\text{cosine}}}{I{\text{reference}}}, \quad S = \frac{I{\text{sine}}}{I{\text{reference}}} ]

- Plot phasor coordinates for each pixel on 2D phasor plot

- Apply clustering algorithms to identify distinct spectral signatures

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If phasor points appear compressed, adjust LCVR voltage to optimize spectral range

- For low signal-to-noise, increase exposure time or sample concentration

- Verify polarization alignment using control samples

Protocol 2: NIR Fluorescence Hyperspectral Imaging of Fluorophores

Purpose: To distinguish NIR fluorophores with closely spaced emission peaks using HyperNIR phasor analysis [2].

Materials:

- NIR fluorophores (e.g., single-walled carbon nanotubes, organic NIR dyes)

- Appropriate solvent and sample chambers

- Excitation source matched to fluorophore absorption

- HyperNIR system calibrated per Protocol 1

Procedure:

Sample Preparation

- Prepare fluorophore solutions at optimal concentrations for detection

- For comparison, select fluorophores with emission peaks separated by <10 nm

- Deposit samples in designated wells or imaging chambers

Image Acquisition

- Set excitation wavelength appropriate for target fluorophores

- Acquire sine, cosine, and reference images for each sample

- Ensure minimal bleed-through between channels

Data Analysis

- Transform each pixel to phasor space

- Identify clusters corresponding to different fluorophores

- Calculate phasor distance between fluorophore species

- Verify separation of fluorophores with <5 nm peak separation

Validation

- Compare with conventional spectrometer measurements if available

- Confirm linear combination properties by analyzing mixed samples

Protocol 3: Label-Free Hyperspectral NIR Reflectance Imaging

Purpose: To identify material compositions and monitor biological processes without labeling using NIR reflectance hyperspectral imaging [2].

Materials:

- Test materials (plastic polymers, plant samples)

- Reference standards for validation

- HyperNIR system with reflectance illumination

Procedure:

System Configuration for Reflectance

- Arrange illumination at appropriate angle to minimize specular reflection

- Set spectral range to target specific molecular vibrations (O-H, C-H, N-H bonds)

- Optimize camera exposure for reflectance mode

Sample Imaging

- Position samples to ensure flat field of view

- Acquire hyperspectral dataset using three-image protocol

- Include background reference measurements

Spectral Analysis

- Transform reflectance data to phasor space

- Identify distinct clusters for different materials

- For plant samples, monitor phasor position shifts indicating water content changes

Data Interpretation

- Correlate phasor positions with known material properties

- Track temporal changes in phasor coordinates for dynamic processes

- Generate false-color maps based on phasor cluster membership

Performance Metrics and Applications

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of HyperNIR Spectral Phasor Imaging

| Parameter | Performance | Comparison to Conventional HSI |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Speed | 0.2 s⁻¹ frame rate | 10-100x faster than scanning methods [21] |

| Spectral Resolution | <5 nm fluorophore separation | Comparable to scanning spectrophotometers [2] |

| Spatial Resolution | Full camera resolution maintained | Superior to mosaic-pattern snapshot cameras [2] |

| Spectral Range | Tunable from 900-1600 nm | Adaptable versus fixed-range systems [2] |

| Light Throughput | 64% average filter transmission | Higher than dispersive scanning systems [21] |

| Cost | ~2000 € for core components | Significantly less than custom interference filters [2] |

Table 2: Application Examples for HyperNIR Spectral Phasor Imaging

| Application Domain | Specific Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Biomedical Imaging | Metabolic imaging of live tissues [21] | Minimal phototoxicity enables long-term imaging |

| Environmental Monitoring | Plastic polymer identification [2] | Label-free chemical discrimination |

| Agricultural Science | Plant water uptake monitoring [2] | Non-destructive temporal tracking |

| Cell Biology | Organelle tracking in 3D cultures [21] | High speed enables 5D (x,y,z,λ,t) imaging |

| Drug Development | Membrane order assessment with environment-sensitive dyes [22] | Fit-free analysis of complex systems |

| Food Safety | Bacterial biofilm detection [23] | Rapid, non-contact inspection |

Data Analysis Workflow

The phasor analysis approach provides a fit-free method for analyzing hyperspectral data without requiring a priori knowledge of spectral profiles, which is particularly valuable in complex biological systems where reference spectra may be unavailable or variable [21].

Phasor Transformation Mathematics

For each pixel in the hyperspectral image, the real (G) and imaginary (S) components of the spectral phasor are calculated using the following transformations:

[ G = \frac{\int{\lambda{\text{min}}}^{\lambda{\text{max}}} I(\lambda) \cos \left( 2\pi n \frac{(\lambda - \lambdai)}{\lambda{\text{max}} - \lambda{\text{min}}} \right) d\lambda}{\int{\lambda{\text{min}}}^{\lambda_{\text{max}}} I(\lambda) d\lambda} ]

[ S = \frac{\int{\lambda{\text{min}}}^{\lambda{\text{max}}} I(\lambda) \sin \left( 2\pi n \frac{(\lambda - \lambdai)}{\lambda{\text{max}} - \lambda{\text{min}}} \right) d\lambda}{\int{\lambda{\text{min}}}^{\lambda_{\text{max}}} I(\lambda) d\lambda} ]

where (I(\lambda)) represents the intensity as a function of wavelength, (n) is the harmonic number, and (\lambda_i) is the initial wavelength [22]. In the HyperNIR implementation, these integrals are effectively computed optically through the sine and cosine filtering approach, with normalization provided by the reference image [2].

Linear Combination Property

A key advantage of the phasor approach is the linear combination property, which states that mixtures of spectral components appear along straight lines between the pure components in the phasor plot [22] [21]. This enables:

- Quantitative determination of component ratios without reference spectra

- Identification of unknown spectral species through geometric relationships

- Model-free analysis of complex systems with multiple interacting components

- Resolution of subtle spectral differences between similar biological states

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HyperNIR Experiments

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Crystal Variable Retarder | Generates wavelength-dependent retardation | Core component of HyperNIR system [2] |

| NIR Linear Polarizers | Filters specific polarization components | Creates spectral filtering with LCVR [2] |

| Environment-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., LAURDAN) | Report on local environmental properties | Membrane order and hydration studies [22] |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes | NIR fluorescent nanomaterials | Biosensor development and deep-tissue imaging [2] |

| NIR Fluorophores with Narrow Emission | Spectral fingerprinting references | System calibration and validation [2] |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration and validation | System performance verification [2] |

Integration in Biomedical Research

The HyperNIR spectral phasor approach enables several advanced applications in biomedical research and drug development. For brain tumour surgery, hyperspectral imaging has demonstrated potential as an intraoperative guidance tool, with one study achieving 70.2% median macro F1-Score for tumour identification using machine learning classification [20]. The phasor method enhances these applications by providing rapid spectral information without the computational overhead of traditional hyperspectral analysis.

In membrane biology research, the combination of environment-sensitive dyes like LAURDAN with spectral phasor analysis has provided insights into membrane order and hydration [22] [24]. The phasor approach surpasses conventional generalized polarization (GP) analysis by utilizing the entire spectrum rather than just two wavelength bands, enabling detection of subtle heterogeneities and intermediate states [22].

The minimal phototoxicity and high imaging speed of phasor-based hyperspectral snapshot microscopy also enables metabolic imaging of live, three-dimensional mouse tissues and tracking of multiple organelles in 3D cultured cells over time [21]. These capabilities make the technology particularly valuable for drug development applications where understanding spatial-temporal dynamics of drug distribution and effect is crucial.

Spectral phasor transformation via the HyperNIR system represents a significant advancement in NIR hyperspectral imaging, addressing the critical limitation of acquisition speed while maintaining high spectral resolution. The direct optical transformation of spectral information into phasor space enables rapid, fit-free analysis of complex biological and materials systems. With applications spanning from biomedical research to environmental monitoring, and its compatibility with standard microscopy platforms, this approach promises to make high-speed hyperspectral imaging accessible to a broad research community. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide researchers with a foundation for implementing this powerful technology in their experimental workflows.

In biomedical research, the drive to observe dynamic processes within living systems using fluorescence microscopy is fundamentally constrained by the photon budget. This concept refers to the finite number of photons that can be collected from a sample before biological integrity is compromised by photobleaching or phototoxicity. This limitation creates an inescapable trade-off between spectral, spatial, and temporal resolution [25] [26]. Hyperspectral imaging (HSI), which captures the full spectrum of light at each pixel, exacerbates this challenge by dividing the photon signal across numerous spectral dimensions [1]. Consequently, a critical need exists for innovative imaging strategies and computational approaches that maximize information extraction from every collected photon. This application note details the underlying principles of these trade-offs and provides validated protocols to guide researchers in optimizing experimental design for hyperspectral biofluorescence characterization, particularly in drug development and live-cell studies.

Quantitative Analysis of Resolution Trade-offs

The following tables summarize the key trade-offs and performance characteristics of different HSI modalities, providing a quantitative foundation for experimental planning.

Table 1: Impact of Resolution Enhancement on Imaging Parameters

| Resolution Type | Spatial Cost | Temporal Cost | Photon Budget Cost | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Spectral | Reduced field of view or spatial sampling | Increased acquisition time per frame | Signal divided across many spectral channels | Spectral unmixing of multiple fluorophores [27] |

| High Spatial | --- | Reduced frame rate or smaller FOV | Signal divided across many pixels | Subcellular localization, fine structure analysis |

| High Temporal | Reduced spatial and/or spectral sampling | --- | Lower signal-to-noise per time point | Live-cell kinetics, rapid signaling events [26] |

Table 2: Comparison of Hyperspectral Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Spectral Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Photon Efficiency | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emission-Scanning HSI [26] | High (0.5 nm achievable) [28] | Lower (sequential channel capture) | Lower (signal loss through filtering) | High spectral fidelity of emission profiles |

| Excitation-Scanning HSI [29] [26] | High (dependent on light source) | Moderate to High | Higher (>10x signal vs emission-scanning) [26] | Detects all emitted photons; reduced photobleaching |

| Single-Shot HSI (e.g., SHy-Cam) [25] | Moderate | Very High (single exposure) | High (avoids sequential scanning) | Enables full-speed volumetric multiplexing in vivo |

| Full-Spectral FLIM [28] | Very High (512 channels) | Lower (6 s for 256x256 image) | Lower (high-dimensional data) | Simultaneous spectral & lifetime information |

Experimental Protocols for Optimizing the Photon Budget

This protocol is designed for kinetic studies of cell signaling, such as Ca²⁺ flux, where maintaining viability and high temporal resolution is critical [26].

1. Equipment and Reagent Setup

- Microscope Platform: Inverted widefield fluorescence microscope.

- Excitation Light Source: Wavelength-specific LED array illuminator with a Cassegrain-style optical combiner [29].

- Detection: Scientific CMOS or EMCCD camera with high quantum efficiency.

- Cells and Reagents: Human Airway Smooth Muscle Cells (HASMCs); culture media; fluorescent Ca²⁺ indicator dye (e.g., Cal-520 or Fluo-4); laminin-coated glass coverslips [26].

2. Sample Preparation

- Seed HASMCs onto laminin-coated 20 mm glass coverslips and culture for 48 hours to 70-80% confluency in standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Load cells with the cell-permeable Ca²⁺ indicator dye according to manufacturer instructions. Incubate for 30-45 minutes at 37°C, followed by a wash step with fresh media.

- Mount the coverslip in a live-cell imaging chamber on the microscope stage, maintaining physiological temperature and CO₂ throughout the experiment.

3. Data Acquisition

- Spectral Calibration: Acquire reference images of control cells (unlabeled) to establish the autofluorescence spectral signature.

- Excitation Scan: Set the acquisition software to sequentially cycle through the pre-defined LED excitation wavelengths (e.g., 20-30 bands across the visible spectrum). For each wavelength, acquire a single image frame with exposure times between 50-200 ms.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Repeat the entire excitation scan cycle over the desired time course (e.g., every 10-30 seconds for 30 minutes). To initiate signaling, add the agonist of interest (e.g., histamine) during the time-lapse sequence.

4. Data Processing and Analysis

- Algorithm Selection: Process the hyperspectral data cube using the Matched Filter (MF) or Linear Unmixing (LU) algorithm, which have shown superior performance for quantifying Ca²⁺ signals against autofluorescence [26].

- Pixel Filtering: Apply a signal intensity threshold (e.g., 10x the background noise level) to exclude pixels with signals below the minimum detectable limit, which enhances the accuracy of kinetic traces [26].

- Kinetic Trace Extraction: Generate quantitative traces of Ca²⁺ flux over time by plotting the unmixed signal intensity from regions of interest (ROIs).

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for excitation-scanning HSI of live-cell calcium signaling.

Protocol: Single-Shot Hyperspectral Phasor Analysis for Multiplexed Imaging

This protocol leverages a single-shot hyperspectral phasor camera (SHy-Cam) to rapidly unmix multiple fluorescent labels, ideal for sensitive samples where light exposure must be minimized [25] [27].

1. Equipment and Reagent Setup

- Imaging System: Single-shot hyperspectral phasor camera system (e.g., SHy-Cam) integrated with a widefield or light sheet microscope [25].

- Software: Original MATLAB code for SHy-Cam pre-processing and phasor-based linear unmixing (available from referenced GitHub repository) [25].

- Samples: Biological samples (e.g., zebrafish, fixed tissues) labeled with 3+ fluorophores with overlapping spectra.

2. System Configuration and Calibration

- Ensure the hyperspectral camera is properly calibrated for spectral response according to the manufacturer's specifications.

- In the control software, define the spatial and spectral sampling parameters. The single-shot nature of the system means no sequential scanning is required.

- For phasor analysis, pre-load or acquire reference spectral signatures for the fluorophores used, if available.

3. Data Acquisition

- Single-Exposure Capture: Illuminate the sample with broad-spectrum light suitable for all fluorophores. Acquire the hyperspectral image data in a single camera exposure.

- Volumetric Imaging (Optional): For 3D samples, perform a Z-stack, capturing a single-shot hyperspectral image at each focal plane. The high speed of acquisition enables full-speed volumetric multiplexing [25].

4. Data Processing and Unmixing

- Phasor Transformation: Process the raw hyperspectral cube using the phasor analysis algorithm. This transformation projects the complex spectral data at each pixel into a 2D phasor plot [27].

- Semi-Automated Unmixing: Utilize the hybrid phasor/linear unmixing approach. This method automates the separation of different fluorescent signals without requiring the user to manually interact with the phasor plot, simplifying the workflow [27].

- Component Visualization: Review the unmixed channels to verify correct separation of each fluorophore's signal and generate the final composite image.

Figure 2: Workflow for single-shot hyperspectral phasor imaging and analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Hyperspectral Fluorescence Imaging

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength-Specific LED Array [29] | Provides rapid, narrow-band excitation light for excitation-scanning HSI. | Live-cell Ca²⁺ signaling studies [26]. |

| Thin-Film Tunable Filter (TFTF) | An alternative for spectral filtering in emission-scanning HSI. | Filter-wheel based HSI of fixed samples [26]. |

| Supercontinuum White Light Laser [28] | A bright, broadband laser source for excitation. | Full-spectrum fluorescence lifetime imaging (FS-FLIM) [28]. |

| Single-Shot Hyperspectral Camera [25] | Captures the entire spectral data cube in a single exposure. | Fast, multi-color fluorescence microscopy in vivo [25]. |

| Phasor Analysis Software [25] [27] | Simplifies and improves the accuracy of spectral unmixing. | Discriminating multiple labels with significant spectral overlap [27]. |

| Linear Unmixing (LU) Algorithm [26] | A standard computational method to separate overlapping fluorescence signals. | Quantitative analysis of excitation-scanning HSI data [26]. |

| Matched Filter (MF) Algorithm [26] | A target detection algorithm that maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio for a known signature. | Detecting weak fluorescent signals against strong autofluorescence [26]. |

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Workflows and Cutting-Edge Biomedical Applications

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique in biomedical research, capable of capturing detailed spatial and spectral information from biological samples. This non-destructive method records a wide spectrum of wavelengths for each pixel in an image, generating complex, high-dimensional datasets often called "hypercubes" [30]. In the specific context of biofluorescence characterization, HSI enables researchers to detect and analyze multiple fluorescent markers or endogenous fluorophores simultaneously, providing unprecedented insight into cellular processes and molecular interactions.

The extraction of meaningful biological information from these complex datasets requires sophisticated chemometric approaches. This application note details practical methodologies for implementing three foundational chemometric techniques—Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), and Soft Independent Modeling of Class Analogy (SIMCA)—specifically for the automated segmentation of bio-traces in hyperspectral images. When properly validated and applied, these methods transform raw spectral data into actionable biological intelligence for drug discovery and development workflows.

Theoretical Foundations of Key Chemometric Techniques

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is an unsupervised dimensionality reduction technique that identifies the principal components (PCs)—orthogonal vectors that capture the maximum variance in the data without using class labels [31]. Informally, the PCA algorithm calculates the first PC along the first eigenvector by minimizing the projection error, then iteratively projects all points to a subspace orthogonal to the last PC and repeats the process [31]. For a data matrix X with n samples and m features, the principal component vectors correspond to the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix. The loading vectors, denoted by L~1~,...,L~n~, are given in terms of the eigenvectors, e~1~,...,e~n~, and the eigenvalues, λ~1~,...,λ~n~, of the covariance matrix C as follows: L~i~ = √λ~i~ e~i~, i = 1, ..., n [31].

Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA)

PLS-DA is a supervised adaptation of PCA that incorporates class label information to maximize the separation between predefined groups [31] [32]. Whereas PCA maximizes variance, PLS-DA maximizes the covariance between the spectral data (X) and the class assignment vector (y) [31]. The iterative process of PLS-DA computes loading vectors that have the highest covariance with the response, making it particularly effective for classification tasks where the goal is to distinguish between different biological states or tissue types [32]. However, as a supervised method, PLS-DA is prone to overfitting and requires rigorous validation [31] [33].

Soft Independent Modeling of Class Analogy (SIMCA)

SIMCA is a class-modeling technique that builds separate PCA models for each class in the training set. During classification, new samples are projected onto each class model, and their fit is evaluated to determine class membership. This approach is particularly valuable in quality control and authenticity testing, where the goal is to verify whether a sample belongs to a specific class rather than simply assigning it to one of several predefined classes.

Experimental Protocols for Hyperspectral Image Segmentation

Sample Preparation and HSI Acquisition

- Biological Sample Preparation: Plate cells or tissue sections of interest. Apply fluorescent probes or biomarkers relevant to the drug mechanism under investigation. Ensure appropriate controls are included (e.g., untreated controls, isotype controls for immunofluorescence).

- HSI System Setup: Configure the hyperspectral imaging system (e.g., push-broom, spectral scanning) to cover the appropriate excitation and emission ranges for your fluorophores. Implement dark current correction and spectral calibration using standard reference materials.

- Image Acquisition: Capture the hyperspectral datacube. The resulting data structure will be a three-dimensional array (x, y, λ) with two spatial dimensions and one spectral dimension.

Data Pre-processing Workflow

- Spectral Correction: Apply dark current subtraction and flat-field correction to minimize instrumental artifacts.

- Spectral Smoothing: Implement Savitzky-Golay filtering or similar techniques to reduce high-frequency noise while preserving spectral features.

- Normalization: Normalize spectra to correct for variations in signal intensity (e.g., using Standard Normal Variate normalization or vector normalization).

- Data Arrangement: Reshape the hypercube into a two-dimensional matrix where each row represents a pixel (x × y) and each column represents a spectral wavelength (λ).

Chemometric Analysis for Segmentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Chemometric Techniques in Hyperspectral Imaging Applications

| Application Area | Technique Used | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Classification | HSI-TransUNet | 86.05% Accuracy | [30] |

| Disease Detection | PLS-DA-based | 98.09% Accuracy | [30] |

| Colorectal Cancer ID | HSI with Classifier | 86% Sensitivity, 95% Specificity | [30] |

| Skin Cancer | HSI with Classifier | 87% Sensitivity, 88% Specificity | [30] |

| Counterfeit Alcohol | HSI with Classifier | 99.03% F1-score | [30] |

Protocol 1: PCA for Unsupervised Pattern Recognition

- Center the Data: Subtract the mean spectrum from each pixel's spectrum in the data matrix.

- Compute Principal Components: Perform singular value decomposition on the covariance matrix of the mean-centered data.

- Determine Significant Components: Use scree plots or cumulative variance explained to select the number of components (d) that capture the majority of variance (typically >95%).

- Generate Score Images: Project the data onto the selected PCs and reshape the scores back into images to visualize spatial patterns corresponding to each component.

- Interpret Loadings: Analyze the loading vectors to identify which spectral features contribute most to each PC, linking them to potential biological or chemical entities.

Protocol 2: PLS-DA for Supervised Classification

- Define Training Set: Select representative regions of interest (ROIs) from the HSI and assign class labels based on known biological features.

- Model Training: Build a PLS-DA model using the training spectra and their associated class labels. The algorithm finds latent variables that maximize covariance between spectral data and class separation [32].

- Cross-Validation: Implement k-fold cross-validation (typically 5- or 7-fold) to determine the optimal number of latent variables and prevent overfitting [31] [32].

- Permutation Testing: Validate model significance by randomly permuting class labels and comparing the performance of the true model with permutation-based null models [33] [32].

- Whole-Image Prediction: Apply the trained model to all pixels in the HSI to generate a classification map.

- Feature Importance: Calculate Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores to identify spectral regions most influential for class discrimination [32].

Protocol 3: SIMCA for Class Modeling

- Build Class Models: For each class of interest, develop a separate PCA model using only training samples from that class.

- Define Acceptance Criteria: Establish critical distance limits for each class model based on the residual variance and score distances of the training samples.

- Classify New Samples: Project each pixel onto all class models and assign it to a class if it falls within the critical distance of that model's space.

- Handle Ambiguity: Pixels may be assigned to multiple classes (overlapping) or no classes (outliers), providing valuable information about classification certainty.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process from sample preparation to segmentation:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for hyperspectral image segmentation using chemometrics, showing key steps from sample preparation to biological interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biofluorescence HSI