Microspectrophotometry in Marine Visual Ecology: Techniques, Applications, and Advances in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of microspectrophotometry (MSP) as a pivotal technique for analyzing visual pigments in marine species.

Microspectrophotometry in Marine Visual Ecology: Techniques, Applications, and Advances in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of microspectrophotometry (MSP) as a pivotal technique for analyzing visual pigments in marine species. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of MSP, detailed methodological protocols for marine applications, and strategies for troubleshooting and data validation. By exploring its use in diverse organisms—from deep-sea crustaceans to flatfish—the content highlights how MSP-derived insights into spectral sensitivity and visual adaptation are informing the discovery of novel bioactive compounds and visual system models with biomedical potential.

Unlocking Marine Vision: The Foundational Role of Microspectrophotometry

Microspectrophotometry (MSP) is a cornerstone technique in visual neuroscience for directly measuring the absorbance properties of visual pigments within individual photoreceptor cells. This method is particularly vital for studying marine species, whose visual systems have evolved complex adaptations to the unique light conditions of aquatic environments. By enabling the analysis of single cells, MSP provides researchers with precise, cell-specific data on spectral sensitivity, revealing the chromatic basis of vision in everything from deep-sea fish to coastal species.

The Core Measurement Principle of MSP

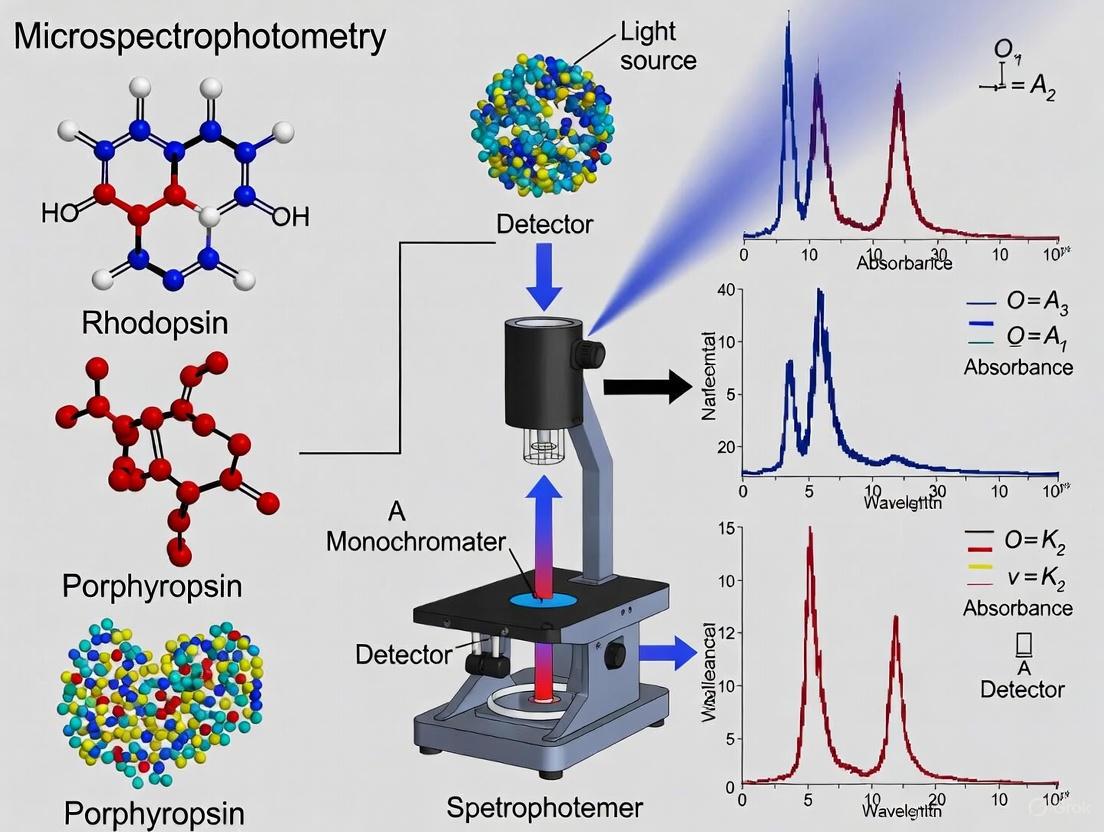

Fundamental Operating Principle

The fundamental principle of MSP is to pass a beam of monochromatic light through a single, isolated photoreceptor cell and measure the proportion of light that is absorbed at each wavelength. Visual pigments, which are housed in the outer segments of photoreceptor cells, have characteristic bell-shaped absorption spectra [1]. The key parameter derived from an MSP measurement is the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax), which denotes the specific wavelength at which the visual pigment absorbs the most light and is a direct indicator of the pigment's spectral sensitivity [1].

The measurement is based on the Beer-Lambert law, which relates the absorption of light to the properties of the material through which the light is traveling. A higher density of visual pigment molecules in the light path results in greater light absorption. The ratio of transmitted light through the cell to a reference beam (often through a blank area of the preparation) is calculated across the spectrum, yielding a transverse absorbance spectrum for that single cell.

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for an MSP experiment, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and Mounting

- Tissue Extraction: Dark-adapt the animal for at least one hour prior to dissection to allow visual pigments to regenerate fully. Under dim, deep-red light, enucleate the eye and hemisect it to remove the retina.

- Photoreceptor Isolation: Place the retinal piece in a droplet of appropriate physiological saline or buffer on a microscope coverslip. Gently macerate the tissue using fine needles or a small vibrator to liberate individual photoreceptor cells.

- Slide Preparation: Introduce a small volume of glycerol-based mounting medium to the suspension to improve optical clarity. Carefully lower a glass microscope slide onto the coverslip to create a sealed preparation. The sample should be kept cool and dark until measurement.

Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

- Microscope Setup: MSP is performed on a modified microscope that combines a high-quality optical microscope with a scanning monochromator and a sensitive photodetector (e.g., a photomultiplier tube or CCD).

- Cell Selection and Alignment: View the sample under infrared light using an infrared-sensitive camera to avoid bleaching the visual pigments. Select an intact photoreceptor and meticulously align its outer segment so it is perfectly positioned in the path of the measuring beam.

- Spectral Scanning: Scan through a range of wavelengths (e.g., from 350 nm to 700 nm), measuring the intensity of light transmitted through the cell (I) and through a reference blank area next to the cell (I~0~) at each wavelength step.

- Bleaching Control: Expose the cell to intense white light for several minutes to photobleach the visual pigment. Repeat the spectral scan to obtain a "bleached" baseline spectrum.

Data Processing and Analysis

- Absorbance Calculation: For each wavelength, compute the absorbance (A) using the formula: ( A = \log{10} (I0 / I) ) This generates a raw absorbance spectrum.

- Baseline Correction: Subtract the bleached spectrum from the raw absorbance spectrum to obtain a difference spectrum, which represents the specific absorbance of the visual pigment.

- Normalization and Curve Fitting: Normalize the difference spectrum to its peak absorbance. Fit a standard visual pigment template curve (e.g., a Govardovskii or Dartnall template) to the data points to determine the precise λmax [2] [3].

Key Data and Applications in Marine Research

Representative MSP Data from Marine Fish

MSP has revealed a remarkable diversity of visual pigments in marine fishes, adapted to their specific photic environments. The table below summarizes example λmax values measured in various species, illustrating this diversity.

Table 1: Visual Pigment λmax Values in Selected Marine Fishes

| Species | Common Name | Photoreceptor Type | λmax (nm) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippoglossus hippoglossus | Atlantic Halibut | Rod | 491 | [2] |

| Single Cone (S) | 431, 457 | [2] | ||

| Single Cone (M) | 500, 514, 527 | [2] | ||

| Single Cone (L) | 550 | [2] | ||

| Mugil cephalus | Flathead Grey Mullet | Rod | 506 | [3] |

| Single Cone (S) | 464 | [3] | ||

| Single Cone (M) | 518 | [3] | ||

| Double Cone (L1/L2) | 560, 574 | [3] | ||

| Pleuronectes americanus | Winter Flounder | Pre-metamorphosis Cone | 519 | [1] |

| Post-metamorphosis Single Cone | 457 | [1] | ||

| Post-metamorphosis Double Cone | 531, 547 | [1] |

These measurements are crucial for understanding visual ecology. For instance, the spectral shift in the rod pigments of deep-sea fish (λmax ~470-490 nm) is an adaptation to the dominant blue light of the deep ocean and the spectrum of bioluminescent emissions [1].

Integrating MSP with Other Techniques

MSP is often used in conjunction with other methods to build a comprehensive understanding of visual systems. As exemplified in a 2022 study on Atlantic halibut, MSP can be correlated with ophthalmic histology to connect spectral sensitivity with retinal structure, and with bioinformatic analysis of the opsin gene repertoire to link functional pigment expression with genetic potential [2]. Another powerful combination is the use of liquid chromatography, as seen in mullet studies, to determine the specific chromophore (e.g., A1- vs. A2-based) used in the visual pigments, which can further tune their λmax [3].

The conceptual relationships between MSP and these complementary disciplines are shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful MSP experimentation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key items and their functions in the protocol.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for MSP

| Item/Category | Specific Examples & Details | Critical Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Saline | Teleost Ringer's solution, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). | Maintains osmotic balance and cellular integrity of photoreceptors during dissection and isolation. |

| Mounting Medium | Glycerol-based solutions (e.g., 50-90% glycerol in buffer). | Provides an optically clear medium that minimizes light scattering for accurate absorbance measurements. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Cocktails (e.g., containing AEBSF, EDTA). | Added to saline to slow proteolytic degradation of visual pigments and outer segments. |

| Microscope & Optics | UV-VIS capable microscope, high-NA objectives, IR light source. | Forms the core platform for visualizing cells (via IR) and delivering/collecting measuring light. |

| Monochromator | Scanning grating monochromator. | Generates a highly pure, wavelength-specific beam of light for the spectral scan. |

| Photodetector | Photomultiplier Tube (PMT), sensitive CCD camera. | Precisely measures the intensity of light transmitted through the single cell. |

The marine environment presents unique challenges for vision, leading to the evolution of highly specialized visual systems. Research into the anatomy of marine vision has revealed remarkable adaptations in photoreceptors, retinal mosaics, and optical structures across diverse species. These adaptations are crucial for survival in various photic niches, from surface waters to the deep sea. Microspectrophotometry (MSP) has emerged as a pivotal technique for investigating visual pigments in marine organisms, allowing researchers to measure absorbance spectra of individual photoreceptor cells and correlate them with molecular genetics and ecological adaptations [2] [4] [5].

The significance of this field extends beyond basic biological understanding, with applications in drug development where marine visual proteins serve as models for human retinal diseases, and in environmental risk assessment where the impact of pollutants on marine visual function is increasingly recognized [6]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for studying marine visual anatomy, with detailed protocols for microspectrophotometry, morphological analysis, and environmental assessment.

Photoreceptor Diversity and Visual Pigments

Photoreceptor Types and Distribution

Marine species exhibit extraordinary diversity in photoreceptor types and organization, reflecting adaptations to their specific ecological niches and visual requirements.

Table 1: Photoreceptor Types in Marine Species

| Species | Photoreceptor Types | Distribution Pattern | Ecological Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) | Single, double, and triple cones | Square mosaic with regional variations | Demersal life style post-metamorphosis [2] |

| Molly Fish (Poecilia sphenops) | Double cones with two single cone variants | Square mosaic pattern throughout retina | Diurnal activity; motion awareness [7] |

| Sea Urchin (Echinoidea) | Distributed photoreceptors with opsins | All-body photoreceptor network | Whole-body light sensitivity without eyes [8] |

| Marine Protists | Four newly discovered photoreceptor groups | Cellular distribution | Daylight synchronization for growth cycles [9] |

In teleost fish like the Atlantic halibut, the retina undergoes dramatic reorganization during metamorphosis from larval to juvenile stages. Pre-metamorphic larvae typically possess a honeycomb mosaic of single cones, which transforms into a square mosaic of single and double cones in juveniles [2]. This transition enables adaptation from a pelagic to demersal lifestyle, with changes in diet from pelagic plankton to benthic invertebrates. The square mosaic configuration typically consists of four double cones arranged around a central single cone, optimizing both spatial resolution and chromatic sensitivity [7].

Visual Pigment Diversity

Visual pigments, consisting of opsin proteins bound to chromophores, determine the spectral sensitivity of photoreceptors. Microspectrophotometry has revealed remarkable diversity in marine visual pigments:

Table 2: Visual Pigments in Atlantic Halibut Identified by Microspectrophotometry

| Photoreceptor Type | Visual Pigment Class | Absorbance Peak (λmax, nm) | Probable Opsin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short wavelength cones | S(431) | 431 nm | SWS1 or SWS2 |

| Short wavelength cones | S(457) | 457 nm | SWS2 |

| Middle wavelength cones | M(500) | 500 nm | RH2 |

| Middle wavelength cones | M(514) | 514 nm | RH2 |

| Middle wavelength cones | M(527) | 527 nm | RH2 |

| Long wavelength cones | L(550) | 550 nm | LWS |

| Rods | Rod pigment | 491 nm | RH1 [2] |

Sea urchins exemplify an extreme adaptation, where the entire body functions as a diffuse photoreceptive structure. They express multiple opsin types and neurotransmitters throughout their nervous system, creating what researchers term an "all-body brain" for distributed light processing [8]. This system enables urchins to respond to light despite lacking discrete eyes, with photoreceptors distributed across their body surface.

Experimental Protocols

Microspectrophotometry for Visual Pigment Analysis

Principle: Microspectrophotometry enables non-destructive measurement of absorbance spectra from individual photoreceptor cells, providing direct data on visual pigment spectral sensitivity.

Reagents and Equipment

- Marine species of interest (freshly collected or properly preserved)

- Physiological saline appropriate for the species

- Glutaraldehyde or other mild fixatives (optional, for stabilization)

- Liquid nitrogen for rapid freezing (if required)

- Multichannel microspectrophotometer system [4] [5]

- Microscope with infrared illumination and imaging capability

- Vibration isolation table to minimize spectral artifacts [4]

- Monochromator or other tunable light source (wavelength range 300-700 nm)

- Computer system with spectral acquisition and analysis software

Procedure

Sample Preparation

- Dark-adapt specimens for at least 2 hours prior to dissection

- Dissect retinal tissue under dim red light using microsurgical tools

- Prepare photoreceptor suspension by gentle mechanical agitation or enzymatic treatment (e.g., papain or hyaluronidase)

- Transfer suspension to microscope slide with coverslip sealed with petroleum jelly to prevent dehydration

Instrument Calibration

- Perform wavelength calibration using standard absorbance filters or rare-earth oxides

- Establish baseline with clear area of slide

- Verify system stability with control measurements

Spectral Measurements

- Identify target photoreceptors using infrared viewing system

- Align measuring beam (typically 1-2 μm diameter) with outer segment

- Scan through wavelength range (e.g., 700-300 nm) to record absorbance spectrum

- Expose to bright light to bleach photopigment and repeat scan

- Calculate difference spectrum to identify visual pigment absorbance [4]

Data Analysis

Retinal Histology and Photoreceptor Mosaic Analysis

Principle: Detailed morphological analysis of retinal structure reveals the organization of photoreceptor mosaics and their relationship to visual function.

Reagents and Equipment

- Fixative solutions (e.g., Bouin's fluid, paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde combination) [7]

- Ethanol series for dehydration (50%, 70%, 90%, 100%)

- Embedding media (paraffin for light microscopy, Araldite for electron microscopy)

- Staining solutions (toluidine blue, hematoxylin and eosin, lead citrate, uranyl acetate)

- Microtomes (rotary for paraffin, ultramicrotome for thin sections)

- Light and electron microscopes with digital imaging capabilities

Procedure

Tissue Fixation and Processing

- Dissect eyes and immerse in appropriate fixative within minutes of sacrifice

- For Bouin's fixation: 22 hours at room temperature [7]

- For ultrastructural analysis: 2.5% paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde combination for 24 hours [7]

- Dehydrate through graded ethanol series, clear with xylene or propylene oxide

- Infiltrate and embed in appropriate medium

Sectioning and Staining

- Cut serial sections at 4-5 μm thickness for light microscopy [7]

- Cut ultrathin sections (70 nm) for transmission electron microscopy [7]

- Stain paraffin sections with Harris hematoxylin and eosin for general morphology

- Stain semithin sections with toluidine blue for photoreceptor identification

- Stain ultrathin sections with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for TEM [7]

Mosaic Analysis

- Identify retinal regions (dorsal, ventral, nasal, temporal)

- Map photoreceptor distribution and density using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ)

- Classify mosaic patterns (honeycomb, square, row) based on geometric arrangement

- Correlate mosaic organization with spectral data from MSP

Oil Droplet Adhesion Assessment for Ecological Risk

Principle: Quantifying oil droplet adhesion to marine organisms, particularly fish eggs, provides critical data for environmental risk assessment of oil spills.

Reagents and Equipment

- Fish eggs with adhesive chorion (e.g., haddock, cod)

- Crude oil samples or prepared oil-seawater dispersions

- Dispersant chemicals (e.g., Corexit) for comparison studies

- Flow-through exposure systems with precise temperature control

- Microscopy systems for documenting droplet adhesion

- Chemical analysis equipment for hydrocarbon quantification

Procedure

Experimental Setup

- Prepare oil-seawater dispersions with controlled droplet size distributions

- Characterize droplet size using Coulter counter or laser diffraction

- Measure zeta potential of oil droplets [10]

- Establish flow-through exposure system simulating natural conditions

Exposure Experiments

- Expose adhesive fish eggs to oil dispersions of known concentration

- Vary exposure duration, oil concentration, and droplet size systematically

- Include controls with dispersants alone and untreated seawater

- Maintain appropriate temperature and water quality throughout exposure

Adhesion Quantification

- Document droplet adhesion using microscopy with digital imaging

- Quantify accumulated oil mass per egg using chemical extraction and GC-MS

- Measure developmental abnormalities and mortality rates

- Calculate adhesion probabilities and exposure thresholds [6]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Marine Vision Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Bouin's fluid, Paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde, Hartman's fixative [11] [7] | Tissue preservation for histology | Maintain structural integrity during processing |

| Embedding Media | Paraffin, Araldite resin [7] | Sectioning support | Provide structural support for thin sectioning |

| Staining Solutions | Toluidine blue, Hematoxylin & Eosin, Uranyl acetate, Lead citrate [7] | Tissue contrast enhancement | Highlight cellular structures for microscopy |

| Molecular Probes | Anti-GFAP, Anti-Rhodopsin, Anti-Calbindin, ViewRNA probes [11] [7] | Cellular localization | Identify specific proteins or mRNA in tissue |

| Enzymes | Papain, Hyaluronidase | Photoreceptor isolation | Dissociate retinal tissue for single-cell analysis |

| Buffers | Phosphate buffer, Sodium citrate, Tris-EDTA [11] | pH and osmotic maintenance | Maintain physiological conditions during processing |

| Optical Standards | Rare-earth oxides, Absorbance filters | MSP calibration | Verify wavelength accuracy and system performance |

Advanced Techniques and Applications

Molecular Histology Integration

Combining microspectrophotometry with molecular techniques provides a comprehensive understanding of visual system function:

Single-molecule Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (smFISH) enables precise localization of opsin mRNA transcripts within retinal sections. When combined with immunofluorescence for opsin proteins and MSP for functional characterization, this approach reveals relationships between gene expression, protein localization, and spectral sensitivity [11]. Critical steps include:

- RNAse-free handling throughout sample processing

- Antigen retrieval pretreatments for formalin-fixed tissues

- Multiplexed detection with spectrally distinct fluorophores

- Controls for specificity and autofluorescence

Environmental Impact Assessment

The adhesion of oil droplets to marine organisms represents a significant environmental threat that requires specialized assessment protocols [6]:

Field Sampling

- Collect water samples during and after oil spills

- Document oil droplet size distributions and concentrations

- Capture affected organisms for adhesion assessment

Laboratory Analysis

- Quantify hydrocarbon composition of adhered droplets

- Measure developmental impacts on early life stages

- Determine threshold concentrations for adverse effects

Modeling Exposure Scenarios

- Implement individual-based models of organism movement

- Simulate oil dispersion under various environmental conditions

- Predict population-level impacts from individual exposure data

The integrated study of photoreceptors, retinal mosaics, and environmental interactions provides crucial insights into marine visual systems. Microspectrophotometry serves as a cornerstone technique, enabling direct measurement of visual pigment function that can be correlated with molecular, anatomical, and ecological data. The protocols outlined in this application note provide a comprehensive framework for investigating marine vision across multiple levels of biological organization, from molecular interactions to ecosystem-scale environmental impacts. As research in this field advances, these methodologies will continue to refine our understanding of how marine organisms perceive their visual world and respond to environmental challenges.

Spectral tuning is a fundamental evolutionary process whereby the visual systems of marine species adapt to the specific light qualities of their ecological niches. In aquatic environments, water acts as a spectral filter, selectively absorbing and scattering wavelengths, which creates diverse light habitats from surface waters to the deep sea [12]. This application note details the mechanisms of spectral tuning and provides standardized protocols for investigating visual adaptations in marine species, with a specific focus on microspectrophotometry (MSP) as a core analytical technique. The information is framed within the context of a broader thesis research project utilizing MSP for visual pigment analysis, providing essential methodologies and reagent solutions for researchers and scientists in the field.

Key Mechanisms of Spectral Tuning

Evolution has equipped marine organisms with multiple, often complementary, mechanisms to fine-tune their visual sensitivity to ambient light. The table below summarizes the primary spectral tuning mechanisms identified in marine fish and other vertebrates.

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Spectral Tuning in Marine Species

| Mechanism | Functional Principle | Biological Example | Spectral Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Substitutions in Opsins | Changes in key amino acids in the opsin protein alter the interaction with the chromophore [12]. | Convergent evolution in primate LWS opsins and Characiform fish LWS-paralogs [12]. | Large (e.g., ~75 nm) or small (2-10 nm) shifts in λmax [12]. |

| A1/A2-Chromophore Shift | Switching the chromophore from 11-cis retinal (A1) to 11-cis 3,4-dehydroretinal (A2) [13]. | Marine fish like the masked greenling (Hexagrammos octogrammus) and prickleback (Pholidapus dybowskii) [13]. | Red-shifts the λmax of the visual pigment [12] [13]. |

| Gene Duplication & Loss | Whole-genome or gene-specific duplications provide genetic material for neofunctionalization [12]. | Characiform-specific duplication of LWS- and RH1-opsins following teleost-specific genome duplication (TGD) [12]. | Creates new visual pigments with distinct spectral sensitivities [12]. |

| Differential Opsin Expression | Varying the relative expression levels of different opsin genes in the retina [12]. | Characiforms base color vision on expression of LWS-paralogs and SWS2 [12]. | Modifies the retina's overall spectral sensitivity without changing pigment λmax. |

| Optical Filters (Oil Droplets) | Colored oil droplets in cone photoreceptors act as long-pass filters [14]. | Avian species like the whooping crane; R-type droplets (λcut 576 nm) in LWS cones [14]. | Narrows photoreceptor spectral sensitivity and reduces overlap between cone types [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Visual Pigment Analysis

Protocol: Microspectrophotometry (MSP) of Photoreceptors

Objective: To measure the absorbance spectrum (λmax) of visual pigments in individual retinal photoreceptor cells.

Materials:

- Dark-adapted retinal tissue

- Physiological saline solution

- Microspectrophotometer

- Glass slides and cover slips

- Software for template fitting (e.g., Govardovskii et al. 2000 templates)

Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Euthanize the specimen following approved IACUC protocols. Enucleate the eye and hemisect it under dim red light. Remove the retina and place it in physiological saline.

- Cell Suspension: Gently homogenize the retinal tissue to create a suspension of individual photoreceptor cells.

- MSP Measurement: Transfer a small aliquot to a microscope slide. Using the microspectrophotometer, target single rods or cones and measure the absorbance spectrum across visible wavelengths.

- Data Analysis: Fit the recorded absorbance spectrum to known visual pigment templates to determine the λmax. For pigments containing an A1/A2 mixture, the data may be best fitted by a combination of templates [13].

Protocol: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for Chromophore Analysis

Objective: To quantify the relative proportions of A1 (11-cis retinal) and A2 (11-cis 3,4-dehydroretinal) chromophores in the retina.

Materials:

- Retinal tissue

- HPLC system with a UV-Vis detector

- Normal-phase HPLC column

- Organic solvents (e.g., hexane, ethyl acetate)

- Standard solutions of A1 and A2 chromophores

Procedure:

- Chromophore Extraction: Homogenize the retinal tissue in a buffer. Extract retinoids using organic solvents.

- Derivatization: Convert the chromophores to their corresponding oximes to stabilize the 11-cis isomers.

- HPLC Analysis: Inject the sample onto the HPLC column. Elute using a gradient of organic solvents and detect the oximes at 360 nm.

- Quantification: Identify A1 and A2 oxime peaks by comparing their retention times to known standards. Calculate the A1:A2 ratio based on peak areas [13].

Protocol: Investigating Chromophore Conversion with Light/Dark Adaptation

Objective: To study the effects of light regime on the A1/A2 chromophore ratio in marine fish retinas.

Materials:

- Live fish specimens

- Controlled environment aquaria with adjustable lighting

- Equipment for MSP and HPLC (as above)

Procedure:

- Acclimation: Maintain one group of fish under a bright light adaptation regime (e.g., 12h light/12h dark) and another under dark adaptation (e.g., continuous darkness) for a period of 4-5 weeks. Control for water temperature.

- Sample Collection: After the acclimation period, euthanize the fish and harvest retinal tissues under dim red light.

- Analysis: Perform MSP and HPLC analysis on the retinal samples as described in Protocols 3.1 and 3.2.

- Comparison: Compare the λmax values from MSP and the A1:A2 ratios from HPLC between the light- and dark-adapted groups. Note: Some marine fish show an unusual increase in A2 proportion after light exposure, a reversal of the common pattern [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents for conducting research on spectral tuning and visual pigment analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Visual Pigment Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 11-cis Retinal (A1) | Chromophore standard for HPLC; reconstitution of visual pigments in vitro [12] [13]. | Essential for determining A1:A2 ratio and for in vitro expression studies. |

| 11-cis 3,4-Dehydroretinal (A2) | Chromophore standard for HPLC; reconstitution of visual pigments in vitro [13]. | Used to quantify the A2 component in retinal extracts. |

| Opsin Expression Vectors | In vitro synthesis of visual pigments for spectral characterization [14]. | Allows for the measurement of λmax without the need for native tissue. |

| Govardovskii Template Equations | Computational tool for determining λmax from MSP absorbance data [13]. | Standard method for analyzing MSP spectral data. |

| Physiological Saline Solution | Maintenance of retinal tissue viability during dissection and preparation. | Typically an isotonic, buffered solution. |

| Normal-Phase HPLC Column | Chromatographic separation of A1 and A2 chromophore oximes [13]. | Critical for accurate quantification of chromophore ratios. |

Experimental Workflow and Chromophore Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a comprehensive research project investigating spectral tuning, integrating the protocols described above.

Research Workflow for Spectral Tuning Analysis

The biochemical pathway of chromophore conversion is central to one key mechanism of spectral tuning. The following diagram outlines this process.

A1/A2 Chromophore Conversion Pathway

Microspectrophotometry (MSP) is an indispensable technique in marine visual ecology, enabling researchers to characterize visual pigments in aquatic species by measuring their spectral absorbance properties. This methodology provides critical insights into how marine organisms perceive their light-attenuated underwater environments. The technique's particular value lies in its ability to analyze minute retinal samples directly, yielding precise data on photoreceptor spectral sensitivity that correlates with specific visual behaviors and ecological adaptations. For marine researchers investigating visual pigment diversity, MSP offers the resolution needed to document the complex visual systems that have evolved in response to the unique photic conditions of aquatic habitats.

The integration of multichannel detectors with MSP systems has significantly advanced the field, allowing for simultaneous measurements across multiple wavelengths and dramatically improving data acquisition efficiency. This technological synergy is especially valuable when working with marine species that may possess multiple visual pigment classes within a single retina—a common adaptation to variable light conditions at different depths. This application note details the essential toolkit and methodologies for employing MSP in marine visual pigment research, providing structured protocols, data presentation standards, and analytical frameworks tailored to the unique challenges of aquatic visual systems.

Technical Specifications & Data Presentation

Key Performance Metrics for Marine Visual Pigment Analysis

Microspectrophotometers deployed in marine visual research must meet specific performance criteria to accurately characterize the diverse visual pigments found in aquatic species. The following table summarizes essential technical specifications optimized for visual pigment analysis:

Table 1: Microspectrophotometer Technical Specifications for Visual Pigment Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Range | 350-750 nm | Covers UV to far-red spectrum; essential for marine species with UV sensitivity [15] |

| Spectral Bandwidth | ≤ 2 nm | Sufficient resolution to distinguish closely-spaced visual pigment λmax values |

| Photometric Accuracy | ±0.003 absorbance units | Critical for detecting small absorbance changes in visual pigment measurements |

| Spatial Resolution | 1-2 μm spot size | Enables measurement of individual photoreceptor outer segments |

| Detector Type | Multichannel CCD or CMOS | Simultaneous multi-wavelength detection reduces measurement time and photobleaching [15] |

| Beam Switching Frequency | 200-400 Hz | Minimizes photopigment bleaching during scanning procedures |

Quantitative Visual Pigment Data from Marine Species

MSP analysis of marine species reveals remarkable diversity in visual pigment composition, reflecting adaptations to specific photic environments. The following table presents representative absorbance data (λmax values) from various marine taxa:

Table 2: Visual Pigment Absorbance Maxima (λmax) in Marine Species

| Species | Photoreceptor Type | Visual Pigment λmax (nm) | Ecological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) | Rod | 491 | Demersal lifestyle; metamorphic visual system reorganization [2] |

| SWS Cone | 431, 457 | Multiple short-wave pigments for enhanced contrast in blue-shifted marine light | |

| MWS Cone | 500, 514, 527 | Middle-wavelength discrimination in variable depth habitats | |

| LWS Cone | 550 | Potential benthic prey detection against substrate | |

| Winter Flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) | Pre-metamorphic Cone | 519 | Larval pelagic phase visual requirements [2] |

| Post-metamorphic SWS Cone | 457 | Benthic juvenile phase with expanded spectral sensitivity | |

| Post-metamorphic LWS Cone | 531, 547 | Substrate discrimination and predator detection |

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Protocol for Marine Retinal Tissue

Principle: Proper preparation of retinal tissue from marine species is critical for preserving visual pigment integrity and obtaining accurate spectral measurements. This protocol outlines standardized procedures for handling diverse marine retinal samples.

Materials:

- Marine Ringer's solution (species-appropriate osmolarity)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Glutaraldehyde solution (2.5% in buffer)

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Tungsten or glass microtools for dissection

- Liquid nitrogen for flash freezing (optional)

Procedure:

Tissue Extraction and Initial Processing

- Euthanize specimen following institutional animal care guidelines

- Enucleate eyes and hemisect at the ora serrata under dim red light

- Remove vitreous humor carefully using fine forceps

- Isolate retinal tissue and transfer to marine Ringer's solution

Photoreceptor Isolation

- For rod-dominant species: gently agitate retinal pieces to dissociate outer segments

- For cone-dominant species: use fine vibration or enzymatic digestion (0.01% trypsin for 5-10 minutes) to liberate photoreceptors

- For flatfish species during metamorphosis: note retinal quadrant origin due to mosaic heterogeneity [2]

Sample Mounting

- Transfer suspension to clean microscope slide

- Allow photoreceptors to settle for 2-3 minutes

- Carefully aspirate excess fluid without allowing complete drying

- Apply coverslip, sealing edges with vacuum grease to prevent dehydration

Quality Control Checks

- Verify photoreceptor structural integrity using differential interference contrast microscopy

- Assess for bleaching by comparing initial and post-measurement absorbance

- Document sample orientation and photoreceptor type (rod, single cone, double cone)

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If photoreceptors show signs of bleaching, implement more stringent dim-light conditions

- For samples with poor adhesion, use poly-L-lysine coated slides

- When measuring multiple cone types, document spatial relationships for mosaic analysis

MSP Measurement Protocol for Visual Pigment Characterization

Principle: This protocol details the specific steps for acquiring absorbance spectra from marine photoreceptors using microspectrophotometry, with emphasis on preserving pigment integrity and ensuring measurement accuracy.

Materials:

- Microspectrophotometer with multichannel detector

- Calibration standards (didymium glass, neutral density filters)

- Data acquisition software with bleaching correction algorithms

- Reference beam neutral density filter (if required by system)

Procedure:

System Calibration

- Wavelength calibration using holmium oxide or didymium glass standard

- Photometric calibration using neutral density filters of known transmission

- Background measurement with clear area of slide adjacent to sample

Sample Alignment and Measurement

- Locate intact photoreceptor using dim infrared illumination with image converter

- Align measuring beam to pass through outer segment longitudinally

- Position reference beam through clear area adjacent to cell

- For double cones in marine species: align beam through individual members separately [2]

Spectral Scanning

- Acquire baseline spectrum from 750nm to 350nm (reverse scan reduces bleaching)

- Repeat scan to verify stability (difference should be <0.005 absorbance units)

- Expose sample to bright white light for 3-5 minutes to bleach visual pigment

- Acquire post-bleach spectrum using identical parameters

Data Integrity Verification

- Calculate difference spectrum (pre-bleach minus post-bleach)

- Verify spectrum meets template fit criteria for visual pigments

- Discard data showing evidence of photoproduct accumulation or photobleaching during initial scan

Technical Notes:

- For species with multiple visual pigments, ensure measuring beam is properly aligned to target specific photoreceptor types

- When working with very small cones from marine fish, reduce beam size to minimize contamination from adjacent cells

- For accurate λmax determination, maintain signal-to-noise ratio >10:1 at peak absorbance

Data Analysis Framework

Functional Data Analysis for Spectral Interpretation

Principle: Functional data analysis provides a robust statistical framework for evaluating MSP evidence, treating absorbance spectra as continuous functions rather than discrete measurements. This approach enhances quantitative comparisons between marine visual pigments.

Likelihood Ratio Calculation: The evidence for whether control and recovered spectra originate from the same source is evaluated using the likelihood ratio (LR), computed as follows [15]:

Where:

- zc and zr represent transformed control and recovered spectral data

- θ represents the group mean with normal distribution N(η, C)

- U represents the fixed covariance matrix for within-group distribution

Implementation Steps:

Spectral Data Transformation

- Represent absorbance spectra using B-spline basis functions: f(x) ≈ Σθₖφₖ(x)

- Select optimal number of basis functions (B) and polynomial order (o) using Akaike's Information Criterion [15]

- Standardize wavelength axis to [0,1] interval to facilitate comparisons

Multivariate Random Effects Modeling

- Model within-group distribution as Z ∼ N(θ, U)

- Model between-group distribution as θ ∼ N(η, C)

- Estimate fixed covariance matrices U and C from training data

Hypothesis Testing Framework

- Hp: Control and recovered spectra originate from same source

- Hd: Control and recovered spectra originate from different sources

- Compute LR support for propositions using multivariate normal density functions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Marine Visual Pigment Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application Function |

|---|---|---|

| Marine Ringer's Solution | Species-specific osmolarity (900-1100 mOsm) | Maintain physiological ionic environment during tissue preparation |

| Digestive Enzymes | Trypsin (0.01-0.1%), Collagenase (0.05%) | Liberate photoreceptors from retinal tissue for individual analysis |

| Fixatives | Glutaraldehyde (2.5% in buffer), Paraformaldehyde (4%) | Structural stabilization for morphological correlation (limited use for MSP) |

| Mounting Media | Glycerol in PBS, Polyvinyl alcohol | Non-fluorescent media for sample preservation during measurement |

| Neutral Density Filters | Certified transmission values (0.1-3.0 OD) | Photometric calibration and reference beam attenuation |

| Wavelength Standards | Holmium oxide, Didymium glass | Accurate wavelength calibration across UV-visible spectrum |

| Opsin Antibodies | Species-specific where available | Immunohistochemical validation of opsin expression patterns |

Workflow Visualization

Marine Visual Pigment Analysis Workflow

Data Processing Pathway

The integrated toolkit of microspectrophotometry with multichannel detection provides marine researchers with a powerful methodology for elucidating visual pigment diversity in aquatic species. The protocols and analytical frameworks presented here offer standardized approaches for collecting robust spectral data while accounting for the unique challenges of marine visual systems. The application of functional data analysis represents a significant advancement over traditional qualitative assessments, enabling quantitative evaluation of spectral evidence within likelihood ratio frameworks. As marine visual ecology continues to explore the complex relationships between visual pigment complement, habitat depth, light environment, and behavioral ecology, these refined MSP methodologies will be essential for documenting and interpreting the remarkable visual adaptations that enable marine species to thrive in diverse photic environments.

From Ship to Lab: MSP Methodologies for Marine Species Analysis

Microspectrophotometry (MSP) serves as a cornerstone technique in visual neuroscience, enabling the direct measurement of visual pigment absorbance within individual photoreceptor cells. This application note provides a detailed protocol for preparing delicate marine biological samples—specifically retinas and isolated rhabdoms—for MSP analysis. Proper sample preparation is paramount for obtaining accurate and reproducible spectral data, as the integrity of visual pigments is easily compromised by improper handling. The methodologies outlined herein are framed within a broader thesis on advancing MSP for marine visual ecology research, offering researchers a standardized approach for investigating the fascinating diversity of marine visual systems.

The primary objective of sample preparation for MSP is to preserve the native state of visual pigments and the structural integrity of photoreceptors until spectral measurements can be performed. Marine samples present unique challenges:

- Rapid Degradation: Visual pigments are inherently photosensitive and begin degrading immediately upon exposure to light post-mortem. This is exacerbated in marine species, whose pigments may be adapted to specific, often cold, environmental conditions [13].

- Structural Fragility: The retinal tissue and rhabdoms of many marine invertebrates and fish are exceptionally soft and easily damaged during dissection and manipulation [16].

- Spectral Complexity: Many marine organisms possess mixed visual pigment systems (e.g., A1/A2 chromophore mixtures) that can be labile and alter with light exposure or temperature changes, requiring preparation techniques that stabilize the native pigment ratio [13].

Success hinges on three core principles: working under appropriate lighting conditions, maintaining physiological conditions where possible, and minimizing mechanical stress on the sample.

Essential Reagents and Equipment

The following toolkit is essential for the preparation of marine retinal samples. Specific reagents mentioned in the literature are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Marine Retina Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde | Light chemical fixation of tissue sections; promotes photobleaching and stabilizes rhabdom structure. | Used at 0.5% in filtered seawater for stomatopod larval sections [16]. |

| Filtered Seawater | Physiological mounting and dissection medium for marine tissue. | Used as a solvent for the glutaraldehyde fixative [16]. |

| Silicone Grease | Creating a sealed chamber between coverslips to contain the sample and mounting medium. | Used to mount cryosections for MSP measurement [16]. |

| Cryostat (Cryomicrotome) | Sectioning frozen retinal tissue into thin slices for MSP measurement. | Used at -30°C to section flash-frozen stomatopod eyes [16]. |

| Difluoroethane Spray | Rapid freezing of dissected tissue to preserve its state and prevent ice crystal formation. | Used to flash-freeze dissected eyes prior to cryosectioning [16]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Animal Handling and Dark Adaptation

- Dark Adaptation: Prior to sacrifice, animals must be fully dark-adapted to ensure visual pigments are in their native, unbleached state. Place the animal in a light-tight container for a period appropriate to its biology. For example, late-stage stomatopod larvae were dark-adapted for a minimum of 3 hours, while early-stage larvae were adapted overnight [16].

- Sacrifice: All subsequent steps must be performed under dim red light, to which most marine visual pigments are insensitive. Sacrifice the animal according to approved ethical guidelines.

Dissection and Tissue Isolation

- Rapid Dissection: Under dim red light illumination, quickly dissect the eyes from the animal. Speed is critical to prevent metabolic changes and post-mortem degradation.

- Primary Fixation/Freezing: Immediately process the isolated eyes. For cryosectioning, flash-freeze the tissue using a cryogen such as difluoroethane spray [16]. Alternatively, some protocols may use light chemical fixation.

Preparation of Retinal Sections

- Cryosectioning: Mount the flash-frozen tissue in a cryomicrotome maintained at -30°C. Section the tissue at a thickness of 10–12 µm [16]. This thickness is optimal for MSP, providing enough pigment density for measurement without excessive light scattering.

- Section Mounting: Transfer the sections to a microscope slide and lightly fix them in a solution of 0.5% glutaraldehyde in filtered seawater for approximately 10 minutes [16]. This step helps stabilize the tissue structure and promotes controlled photobleaching during MSP analysis.

- Coverslip Sealing: Mount the fixed section between two coverslips using a ring of silicone grease to create a sealed chamber containing the mounting medium. This prevents the sample from drying out during measurement.

Preparation of Isolated Rhabdoms

While the search results provide more detail on retinal sections, the preparation of isolated rhabdoms for MSP, as referenced in historical studies, generally follows this workflow [17]:

- Retina Isolation: Dissect the retina under dim red light and place it in a suitable physiological saline.

- Mechanical Separation: Gently homogenize or shred the retinal tissue to release the rhabdoms from the photoreceptor cells.

- Chemical Fixation: Immerse the isolated rhabdoms in a low-concentration glutaraldehyde solution (e.g., as used in fixed drone retinae [17]) to stabilize their structure.

- Mounting: Transfer a small aliquot of the suspension containing rhabdoms onto a microscope slide for MSP measurement.

The following workflow diagram synthesizes the core sample preparation pathway based on the protocols described above.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The ultimate goal of sample preparation is to yield high-quality data on visual pigment absorbance. MSP measurements generate spectral curves, but the preparation method itself is defined by specific parameters. The table below quantifies key aspects of the preparation protocols as found in the literature.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Sample Preparation from Literature

| Protocol Step | Key Parameter | Reported Value / Specification | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dark Adaptation | Duration | Minimum 3 hours to overnight [16] | For stomatopod larvae |

| Cryosectioning | Section Thickness | 10–12 µm [16] | Standard for MSP analysis |

| Cryosectioning | Chamber Temperature | -30°C [16] | For stomatopod larval eyes |

| Chemical Fixation | Glutaraldehyde Concentration | 0.5% [16] | In filtered seawater |

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Poor Signal-to-Noise in MSP: This can result from over-fixation, which destroys the visual pigment, or under-fixation, leading to poor structural integrity. The 0.5% glutaraldehyde concentration is a critical starting point [16].

- Sample Degradation: If pigments appear bleached upon measurement, check for light leaks during dissection or insufficient dark adaptation time. Ensure all steps are performed under strict dim red light conditions.

- Tissue Damage During Sectioning: If the retina is tearing, the freezing process may be too slow, leading to large ice crystal formation. Ensure the tissue is flash-frozen as rapidly as possible after dissection.

Ship-based microspectrophotometry (MSP) is a powerful technique for the in-situ characterization of visual pigments in marine species, enabling researchers to obtain crucial data on the spectral absorbance properties of photoreceptors directly in the field. This methodology is particularly valuable for studies on marine vertebrates and invertebrates where prompt measurement following capture is essential to preserve the native state of visual pigments [18] [19]. However, the marine environment introduces significant technical challenges, with vibration artifacts representing a primary obstacle to obtaining reliable spectral data. Shipboard vibrations, originating from propulsion systems, generators, wave impacts, and onboard machinery, can severely compromise the precision of optical measurements by introducing misalignment, noise, and instability in the microspectrophotometer [20] [21]. These issues are particularly pronounced for modern vessel designs, which have become more optimized and consequently more susceptible to vibration-induced failures that can affect sensitive instrumentation [21].

The problem of structural vibration in ships is well-documented, with flat plate structures constituting the basic structural units of hull components such as cabins, double bottoms, and superstructures [20]. These vibrations propagate through the ship's structure and can disrupt the critical alignment required for measuring minute absorbance spectra in photoreceptor cells. For MSP applications, where measurements often target single cone cells or rods with diameters of just a few micrometers, even sub-micron vibrations can render data unusable [18] [2]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for mitigating vibration artifacts in ship-based MSP systems, ensuring the collection of research-grade spectral data for visual pigment analysis in marine species.

Vibration Characteristics in Marine Environments

Understanding the origin and transmission pathways of shipboard vibrations is fundamental to developing effective mitigation strategies. Marine vessels present a complex vibration landscape with multiple excitation sources operating across different frequency ranges. The primary sources include rotating machinery such as motors, pumps, and fans; propulsion systems including shafts and propellers; and environmental forces from wave impacts and hydrodynamic flow [22] [21]. These vibrations propagate through the ship's structure, predominantly through flat plate components that form the basic structural elements of hull design [20]. The resulting vibrational energy distributes throughout the vessel, creating a challenging environment for sensitive optical instrumentation like microspectrophotometers.

Modern ship designs have exacerbated these challenges through structural optimizations that reduce weight and material usage while potentially increasing vibration susceptibility [21]. The problem is particularly acute in research vessels, which must accommodate both propulsion machinery and scientific equipment in a confined space. Vibration-induced failures in instrumentation can manifest as structural fatigue, component malfunction, and measurement inaccuracies - all of which directly impact the quality of scientific data collection [21]. For MSP systems, which depend on precise optical alignment and stability, these vibrations introduce noise, drift, and misalignment that compromise the integrity of visual pigment measurements.

Vibration Impact on Microspectrophotometry

The detrimental effects of vibration on MSP measurements are multifaceted and particularly problematic when working with the minute samples characteristic of marine organism photoreceptors. The wedge-tailed shearwater study, for instance, required measurements from seven different photoreceptor types including single cones with visual pigments ranging from violet (λmax 406 nm) to long-wavelength (λmax 566 nm) sensitivity [18] [23]. Achieving this resolution demands exceptional stability throughout the measurement process. Vibration-induced misalignment can cause beam deviation, leading to inaccurate absorbance measurements as the light path shifts relative to the microscopic sample. Low-frequency vibrations introduce baseline drift in spectral recordings, while higher-frequency components contribute signal noise that obscures the subtle spectral features of visual pigments.

The problem intensifies when measuring samples from deep-sea species, where visual pigments often exhibit spectral tuning to specific light environments. Studies on cetacean visual pigments have revealed precise spectral tuning of rod pigments to available light at foraging depths, with an inverse relationship observed between the wavelength of maximum sensitivity and depth [24]. Resolving these spectral characteristics requires vibration mitigation strategies that address the full frequency spectrum of shipboard vibrations. Furthermore, the trend toward rod monochromacy in multiple cetacean lineages (including sperm whales, some baleen whales, and beaked whales) means that researchers are often working with a single visual pigment type, making accurate characterization even more critical [25].

Table 1: Characteristic Vibration Sources and Their Impact on MSP Measurements

| Vibration Source | Frequency Range | Primary Impact on MSP | Affected Measurement Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Engines & Propellers | 5-30 Hz | Low-frequency drift | Baseline stability, long-term measurements |

| Generators & Pumps | 30-100 Hz | Medium-frequency oscillation | Absorbance peak resolution, signal-to-noise ratio |

| Wave Impact & Hydrodynamic Forces | 1-20 Hz | Broad-spectrum instability | General measurement reliability, alignment |

| HVAC Systems | 10-50 Hz | Continuous vibration | Precision of λmax determination |

| Auxiliary Machinery | 50-200 Hz | High-frequency noise | Spectral fine structure, measurement precision |

Vibration Mitigation Framework

Instrument Isolation Protocols

Effective vibration mitigation begins with comprehensive instrument isolation designed to decouple the microspectrophotometer from the ship's structure. A multi-layered approach delivers the most significant improvement in measurement stability, particularly for the critical alignment components within the optical path. The primary isolation system should incorporate pneumatic isolators with low natural frequencies (0.5-5 Hz) to address the dominant low-frequency vibrations originating from propulsion systems and wave action [20]. These should be supplemented with damping materials such as sorbothane or specialized polymer composites at instrument contact points to absorb higher-frequency vibrations from generators and rotating machinery.

The optical bench within the MSP system requires specialized attention, as measurements of visual pigment absorbance in marine species demand exceptional stability. Research on marine ostracodes, for instance, identified visual pigment absorbance peaks at approximately 460 nm, with luminescence emission spectra peaking at 473 nm [19]. Resolving these spectral characteristics requires implementing internal passive isolation within the instrument itself, particularly for the monochromator, sample stage, and detector assemblies. Kinematic mounting of optical components, constrained layer damping on flat surfaces, and strategic use of damping alloys for component holders can significantly reduce vibration-induced misalignment and noise. For shipboard installations, additional inertial stabilization of the light source and reference beam path may be necessary, particularly when working with the high magnification objectives required for targeting individual photoreceptor cells.

Operational Procedures and Measurement Techniques

Adapting standard MSP protocols to compensate for residual vibration artifacts is essential for obtaining reliable data in shipboard environments. The measurement workflow should incorporate vibration-aware timing that synchronizes spectral scans with periods of relatively lower vibration, such as when the vessel is maintaining steady speed without course changes or when station-keeping in favorable sea states. During the larval to juvenile transition of Atlantic halibut, researchers documented complex photoreceptor reorganization involving the formation of square mosaics from single cones [2]. Studying such delicate morphological changes requires implementing signal averaging techniques with increased scan repetitions (typically 50-100% more than laboratory standards) to improve signal-to-noise ratio while applying adaptive filtering algorithms that recognize and reject vibration-corrupted scans in real-time.

Sample handling procedures must be optimized to minimize exposure to vibration during critical preparation and measurement phases. For marine species with diverse photoreceptor arrangements, such as the Atlantic halibut which exhibits six cone visual pigments with absorbance maxima ranging from 431 nm to 550 nm [2], precise positioning is essential. Implementing rapid mounting protocols that stabilize samples quickly and utilizing vibration-damped micropositioners for final alignment can preserve sample integrity while minimizing vibration exposure. Additionally, establishing a standardized vibration monitoring protocol using accelerometers mounted to the instrument frame provides quantitative data for correlating vibration levels with measurement quality, enabling post-processing compensation when necessary.

Table 2: Vibration Mitigation Solutions for Ship-Based MSP Components

| MSP Component | Primary Vulnerability | Recommended Solution | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Bench | Structural resonance | Kinematic mounting, damping composites | Reduction of resonant amplification by >60% |

| Light Source | Filament/mirror stability | Secondary isolation platform | Intensity fluctuation <0.5% during scans |

| Monochromator | Grating alignment | Temperature compensation, stiffened mounts | Wavelength shift <0.1 nm during measurement |

| Sample Stage | Positioning accuracy | Piezo-electric stabilization, damped controllers | Positional drift <0.2 μm during single scan |

| Detection System | Detector noise | Vibration-resistant housing, EMI shielding | Noise reduction of 40-60% across spectrum |

| Data Acquisition | Timing errors | Vibration-triggered scan rejection | Automatic rejection of >90% of corrupted scans |

Experimental Protocol for Ship-Based Visual Pigment Analysis

Sample Preparation Under Shipboard Conditions

Preparation of retinal samples for MSP analysis under shipboard conditions demands specialized protocols that account for both the marine environment and vibration constraints. For marine birds like the wedge-tailed shearwater, which possesses five different types of vitamin A1-based visual pigment across seven photoreceptor types [18], immediate processing following collection is essential to preserve pigment integrity. The dissection should be conducted in a stabilized workstation with vibration-damped surfaces, utilizing temperature-controlled chambers to maintain samples at species-appropriate conditions throughout preparation. For most marine species, this ranges between 2-8°C to slow metabolic processes without causing thermal damage to photoreceptor structures.

The mounting procedure requires particular attention to vibration mitigation. Retinal samples should be oriented and secured using UV-polymerizing adhesives rather than mechanical clamping to minimize stress and vibration transmission. For species with complex photoreceptor distributions, such as flatfishes undergoing metamorphic transition from honeycomb to square cone mosaics [2], sectioning should be performed with vibration-stabilized microtomes to preserve structural integrity. The final sample orientation must facilitate rapid identification of target photoreceptors – a particular challenge for deep-diving marine mammals like cetaceans, which may possess only a single visual pigment type [25] [24]. Implementing pre-alignment protocols that establish reference coordinates during calm periods significantly reduces measurement time when vibration conditions temporarily improve.

Vibration-Resilient Measurement Workflow

The spectral measurement protocol must be specifically adapted to compensate for persistent low-frequency vessel vibrations while maintaining the precision required for accurate visual pigment characterization. The following workflow integrates multiple vibration mitigation strategies:

System Stabilization Phase: Allow a minimum of 30 minutes for instrument warm-up and stabilization, with continuous monitoring of vibration levels using integrated accelerometers. During this period, perform preliminary alignment using stable reference materials that simulate sample properties.

Baseline Acquisition: Collect reference spectra with the sample translated clear of the beam path, immediately preceding each sample measurement series. This approach minimizes the impact of low-frequency drift in baseline measurements, which is particularly important for species with violet-sensitive visual pigments like the wedge-tailed shearwater (λmax 406 nm) where signal intensity is naturally lower [18].

Adaptive Scanning Protocol: Implement a scanning strategy that dynamically adjusts integration times based on real-time vibration monitoring. For relatively stable periods (vibration amplitude <0.5 μm), utilize standard integration times of 0.5-1.0 seconds per wavelength step. During higher vibration intervals, switch to shorter integration times (0.1-0.2 seconds) with increased repetition and averaging.

Multi-Spectral Validation: For each measurement location, collect overlapping spectral ranges with varying scan speeds to identify and exclude vibration-induced artifacts. This approach is particularly valuable when characterizing complex visual systems such as those in Atlantic halibut, which exhibits multiple middle-wavelength-sensitive pigments (M(500), M(514), and M(527)) that require precise differentiation [2].

Post-Measurement Verification: Immediately following each spectral measurement, verify sample integrity and positioning through rapid imaging or confirmatory scans. For shipboard analysis of marine ostracodes, which display visual pigment absorbance maxima at approximately 460 nm [19], this verification ensures that vibration has not displaced the measurement area during scanning.

Data Analysis and Artifact Correction

Vibration Identification in Spectral Data

Recognizing and quantifying vibration-induced artifacts in MSP spectra is essential for ensuring data quality and making informed decisions about measurement validity. Vibration corruption typically manifests as increased high-frequency noise, baseline irregularities, and peak position instability – each requiring different identification approaches. For marine species with multiple visual pigment classes, such as the wedge-tailed shearwater with its VS, SWS, MWS, and LWS cone types [18], the impact of vibration varies with the spectral region being measured. Short-wavelength measurements (e.g., violet-sensitive λmax 406 nm) generally show greater susceptibility to vibration-induced noise due to lower photon flux and detector sensitivity in these regions.

The most reliable indicator of vibration contamination is spectral inconsistency between repeated measurements of the same photoreceptor. Implementing a quantitative consistency metric based on the normalized root mean square deviation (NRMSD) between successive scans provides an objective measure of vibration impact. For quality control thresholds, measurements exceeding 5% NRMSD should trigger investigation, while those exceeding 10% warrant rejection and repetition. Additional vibration indicators include abnormal peak broadening beyond the instrument's characteristic point spread function and wavelength-dependent noise patterns that correlate with known vibration frequencies in the vessel. Establishing these criteria is particularly important when studying species like cetaceans, where spectral tuning of visual pigments to depth represents a key adaptive trait [24].

Computational Compensation Methods

When vibration artifacts cannot be eliminated through physical mitigation alone, computational approaches provide a secondary defense for recovering usable spectral data. Adaptive filtering algorithms that utilize reference signals from accelerometers mounted on the instrument can effectively remove vibration-correlated noise components from spectral measurements. These approaches are particularly valuable for long-term monitoring studies where environmental conditions inevitably vary. For species with complex visual pigment complements, such as Atlantic halibut with six cone visual pigments [2], maintaining consistent measurement quality across multiple spectral classes requires frequency-dependent noise suppression tailored to each pigment's characteristic absorbance range.

Spectral reconstruction techniques offer an alternative approach for recovering accurate λmax values from vibration-compromised data. These methods leverage a priori knowledge of visual pigment template shapes [19] to fit partially corrupted spectra, with confidence metrics derived from the goodness of fit to established pigment models. For rod-dominated visual systems like those found in many cetaceans [25] [24], where the spectral tuning range may be relatively constrained, Bayesian estimation methods can incorporate ecological context (e.g., typical foraging depths) to improve reconstruction accuracy. Implementation of these computational compensation methods requires careful validation against laboratory standards and should be documented transparently when reporting research findings.

Research Reagent Solutions for Marine Visual Pigment Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ship-Based Visual Pigment Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Shipboard Adaptation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with stabilizers | Visual pigment extraction and stabilization | Pre-aliquoted, temperature-stable formulations in sealed vials | Extraction of rod visual pigments from cetacean retinas [24] |

| Hydroxylamine hydrochloride | Chromophore bleaching control | Oxygen-impermeable packaging with moisture control | Testing retinoid-based pigment stability in deep-sea fish [26] |

| Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with antioxidants | Tissue preservation during dissection | Pre-mixed, sterile single-use aliquots | Maintenance of photoreceptor integrity in marine bird retinas [18] |

| Siliconizing reagents | Surface treatment for sample holders | Low-volatility formulations for controlled application | Preventing adhesion of fragile photoreceptors in ostracode studies [19] |

| UV-curable optical adhesives | Sample mounting and stabilization | Vibration-resistant formulations with delayed curing | Securing retinal sections from flatfish during metamorphosis [2] |

| Deuterium-tungsten hybrid light source | Broad-spectrum illumination for MSP | Ruggedized design with reinforced filaments | Continuous spectrum for visual pigment mapping in marine species [18] |

| Spectral calibration standards | Wavelength accuracy verification | Stable, non-degrading materials in shock-resistant mounting | Daily validation of MSP precision for whale pigment studies [25] |

Validation and Quality Assurance Protocol

Performance Metrics and Verification Standards

Establishing rigorous quality assurance protocols is essential for validating ship-based MSP data, particularly when vibration mitigation strategies may introduce their own artifacts. The validation framework should incorporate daily system verification using stable spectral standards with known absorbance characteristics across the relevant wavelength range (typically 350-650 nm for marine visual pigments). For each analytical session, baseline performance metrics should include wavelength accuracy (deviation < ±0.5 nm), spectral resolution (bandwidth < 5 nm), and absorbance precision (CV < 2% for repeated measurements) under simulated vessel vibration conditions.

The validation protocol must include biological reference materials that approximate the sample matrix being studied. For marine fish visual pigment analysis, standardized retinal preparations from readily available species with well-characterized visual pigments provide essential method verification. Studies of Baltic Sea fishes, for instance, have documented rod visual pigment spectral shifts between marine and limnic populations [26], providing potential reference systems for method validation. Additionally, implementing intermediate precision testing that evaluates performance across different sea states and vessel operations provides crucial data on the robustness of the vibration mitigation strategy. This approach is particularly valuable for research vessels that transition between transit operations and stationary sampling, as vibration profiles differ significantly between these modes.

Documentation and Reporting Standards

Comprehensive documentation of vibration conditions and mitigation effectiveness ensures the scientific validity of ship-based MSP data and enables meaningful comparison with laboratory studies. Each measurement series should include vibration metadata capturing quantitative vibration levels (frequency spectra and amplitude distributions) during spectral acquisition, specific mitigation strategies employed, and any computational corrections applied during data processing. This documentation is particularly important when reporting subtle spectral differences, such as the rod visual pigment shifts observed between marine and Baltic Sea populations of herring, flounder, and sand goby [26].

The reporting framework should explicitly acknowledge the limitations imposed by the shipboard environment while demonstrating the effectiveness of mitigation strategies through quality control metrics. For studies investigating evolutionary adaptations in visual pigments, such as the parallel spectral tuning observed in whale M/LWS pigments [25], the methodology section should include sufficient detail on vibration control to establish measurement reliability. Implementing these documentation standards across the research community will facilitate the development of improved vibration mitigation strategies and enhance the credibility of ship-based MSP as a technique for in-situ visual pigment analysis.

This application note details the use of microspectrophotometry (MSP) to investigate the dynamic reorganization of photoreceptors and their visual pigments during the metamorphosis of Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus). Metamorphosis in flatfish involves a dramatic transition from bilaterally symmetrical, pelagic larvae to asymmetrical, demersal juveniles, accompanied by profound changes in the retinal architecture and visual pigment complement [2]. This case study aligns with a broader thesis on applying MSP to understand visual ecology in marine species, demonstrating how precise photopigment measurement can reveal adaptations to shifting environmental demands and lifestyles.

The retinal transformation in Atlantic halibut involves a complex transition from a larval honeycomb mosaic of single cones to a juvenile square mosaic incorporating single and double cones [2]. Concurrently, MSP revealed an expansion of the visual pigment repertoire from a pre-metamorphic single cone pigment to at least six distinct cone visual pigments in the juvenile, alongside the emergence of rod pigments for scotopic (dim-light) vision [2]. These findings highlight the utility of MSP in correlating morphological restructuring with functional chromatic diversity, providing a model for studying sensory system plasticity.

Key Quantitative Findings

Temporal Development of Eye Morphology

Table 1: Morphometric changes in the Atlantic halibut eye during metamorphosis. Data sourced from [2].

| Developmental Stage (Accumulated Temperature Units, ATU) | Approximate Days Post-Fertilization | Eye Long Axis (mm) | Eye Short Axis (mm) | Lens Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 720 ATU | 96 days | 1.6 ± 0.18 | 1.3 ± 0.11 | 0.44 ± 0.04 |

| 1170 ATU | 117 days | 2.2 ± 0.13 | 1.6 ± 0.15 | 0.64 ± 0.02 |

Spectral Absorbance of Visual Pigments in Juvenile Halibut

Table 2: Visual pigment diversity in post-metamorphic Atlantic halibut as determined by MSP. Data adapted from [2].

| Photoreceptor Type | Visual Pigment Class | Mean Wavelength of Maximum Absorbance (λmax, nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Rod | RH1 | 491 |

| Single Cone | SWS (Short-Wavelength Sensitive) | 431, 457 |

| Single/Double Cone | RH2 (Middle-Wavelength Sensitive) | 500, 514, 527 |

| Double Cone | LWS (Long-Wavelength Sensitive) | 550 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Microspectrophotometry (MSP) of Retinal Photoreceptors

Principle: MSP measures the absorbance spectrum of visual pigments within individual photoreceptor cells by passing a monochromatic beam of light through the outer segment and comparing it to a reference beam [2] [12].

Materials:

- Fresh or dark-adapted frozen retina from juvenile Atlantic halibut

- Microspectrophotometer

- Microscope with infrared-sensitive camera for cell manipulation

- Physiological saline solution

- Glass slides and cover slips

- Tools for fine dissection

Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Under dim red light, enucleate the eye and hemisect it. Remove the retina and place it in a drop of physiological saline on a glass slide. Gently tease the retinal tissue apart using fine needles to liberate photoreceptor cells. Apply a cover slip [2] [12].

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the MSP with a neutral density filter and ensure the baseline spectrum is stable.

- Cell Selection & Alignment: View the sample using infrared illumination. Identify and align a single photoreceptor outer segment in the measuring beam.

- Spectral Scanning: Scan the monochromatic light across the relevant wavelength range (e.g., 350-650 nm). Record the transmitted light intensity through the cell at each wavelength.

- Data Processing: For each cell, calculate absorbance as a function of wavelength. Fit the resulting absorbance spectrum with a standard visual pigment template to determine the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) [2].

- Chromophore Identification: To confirm the type of chromophore (A1 or A2), expose the pigment to deep red light, which will bleach pigments based on their chromophore type, and note the spectral changes in the difference spectrum [12].

Protocol: Retinal Histology and Photoreceptor Mosaic Analysis

Principle: This protocol details the preparation of retinal cross-sections to visualize and characterize the spatial organization of photoreceptor mosaics at different developmental stages.

Materials:

- Fixative (e.g., 4% Paraformaldehyde in 0.1M Phosphate Buffer)

- Cryostat or microtome

- SuperFrost Plus glass slides

- Stains (e.g., Toluidine blue) or dyes for differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy

- Fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

- Fixation: Immerse dissected eye cups immediately in fixative for 24 hours.

- Tissue Processing: Dehydrate the fixed tissue through a graded ethanol series, clear it, and embed it in paraffin or a resin for high-resolution sectioning. Alternatively, for cryosectioning, immerse the tissue in a sucrose solution before embedding in OCT compound [2] [27].

- Sectioning: Cut thin sections (1-15 μm thickness) using a microtome or cryostat and mount them on glass slides.

- Staining & Imaging: Stain sections with a histological stain like Toluidine blue to enhance contrast or use DIC microscopy to visualize unstained photoreceptor inner and outer segments [2].

- Mosaic Analysis: Image the photoreceptor layer at high magnification across different retinal regions (dorsal, ventral, nasal, temporal). Identify and classify photoreceptors as single, double, or triple cones. Map their spatial arrangement to classify the mosaic type (e.g., honeycomb vs. square) [2].

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated methodology from tissue preparation to data analysis, as applied in the halibut case study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for photoreceptor and visual pigment research.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|