Molecular Imaging Modalities: A Comparative Analysis of Biofluorescence, MRI, CT, and PET

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of major molecular imaging modalities—biofluorescence, MRI, CT, and PET—for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Imaging Modalities: A Comparative Analysis of Biofluorescence, MRI, CT, and PET

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of major molecular imaging modalities—biofluorescence, MRI, CT, and PET—for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, methodological applications, optimization strategies, and comparative validation. The scope includes examining the high sensitivity and real-time capabilities of fluorescence imaging against the deep-tissue penetration and anatomical precision of radiographic techniques, with insights into overcoming inherent limitations through probe development and hybrid imaging. The content also explores future directions, including the integration of deep learning and multimodal approaches, to enhance diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic monitoring in biomedical research.

Core Principles and Instrumentation of Molecular Imaging Technologies

This guide provides an objective comparison of five core molecular imaging modalities: bioluminescence, fluorescence, MRI, CT, and PET. The table below summarizes their fundamental mechanisms and key performance characteristics to inform tool selection for research and drug development.

| Imaging Modality | Fundamental Mechanism | Primary Signal | Key Performance Metric | Quantitative Data (Representative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioluminescence (BLI) | Light emission from enzyme-substrate (e.g., luciferase-luciferin) chemical reaction [1] [2] | Bioluminescent light (photons) | Sensitivity / Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Very high; minimal background light yields excellent signal-to-noise [1] [2] |

| Fluorescence (FLI) | Light emission from fluorophore excited by an external light source [2] | Fluorescent light (photons) | Spatial Resolution / Multiplexing | High; enables multiplexing with different fluorophores [2] |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Emission of radiofrequency signals from hydrogen protons realigning in a strong magnetic field [3] | Radio waves | Soft-Tissue Contrast / Specificity | Sensitivity: 92%; Specificity: 85% (ovarian tumors) [3] |

| Computed Tomography (CT) | Differential absorption of X-rays by tissues [4] | X-rays | Anatomical Detail / Speed | Sensitivity: 68%; Specificity: 94% (colorectal liver metastases) [4] |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | Detection of gamma rays from positron-emitting radiotracer decay [5] | Gamma rays | Metabolic Sensitivity / Quantification | Sensitivity: 61%; Specificity: 99% (colorectal liver metastases) [4] |

Performance Comparison in Research Applications

Lesion Detection and Staging

Direct comparisons in clinical and preclinical oncology highlight trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity.

Table 2: Oncologic Staging Performance (Per-Lesion Analysis)

| Pathology | Modality | Sensitivity | Specificity | Context & Comparative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Liver Metastases [4] | CT | 68% | 94% | MRI demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity, especially for sub-centimeter lesions. |

| MRI | 90% | 87% | ||

| PET/CT | 61% | 99% | ||

| Breast Cancer (Whole-Body) [6] [7] | PET/CT | - | - | Trend toward higher sensitivity for PET/MRI, particularly for liver and bone metastases; PET/CT had higher specificity in some studies [6]. |

| PET/MRI | Higher | - | ||

| Nodal/Distant Staging (NSCLC) [8] | PET/CT | 82% / 86%* | 88% / 89%* | No significant differences reported; modalities have similar value for staging Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer [8]. |

| PET/MRI | 86% / 93%* | 90% / 90%* | ||

| *Sensitivity/Specificity for nodal metastases / distant metastases |

Functional and Metabolic Imaging

- Bioluminescence Imaging: Ideal for longitudinal tracking of tumor growth, gene expression, and cell migration in live animals due to very low background [1] [9]. A key application is developing safer BSL-2 models for studying highly pathogenic viruses via longitudinal BLI [9].

- Fluorescence Imaging: Excels in visualizing protein localization, enzymatic activity, and cellular trafficking with high spatial resolution, though background autofluorescence can be a limitation [1] [2].

- PET-based Modalities: Provide highly sensitive, quantitative mapping of metabolic activity (e.g., with 18F-FDG), specific molecular targets (e.g., with 68Ga-PSMA), or fibroblast activation (e.g., with FAPI tracers) [8] [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging for Tumor Growth Monitoring

This protocol is widely used in oncology research for non-invasive, longitudinal tracking of tumor dynamics [1] [2].

- Cell Line Engineering: Stably transduce tumor cells of interest with a luciferase reporter gene (e.g., Firefly luciferase - Fluc).

- Subject Preparation: Implant luciferase-expressing cells into an appropriate animal model (e.g., mouse).

- Substrate Administration: Once tumors are established, inject the luciferase substrate (e.g., D-luciferin for Fluc) intraperitoneally or intravenously. The standard dose is 150 mg/kg body weight for D-luciferin [1].

- Image Acquisition: Place the animal in a light-tight chamber of a bioluminescence imaging system. Acquire data after a brief incubation period (typically 10-20 minutes for IP injection) to allow for substrate distribution and peak light emission. Exposure times can range from 1 second to several minutes.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the total photon flux (photons/second) within a region of interest (ROI) drawn around the tumor signal. This provides a quantitative measure of tumor burden over time.

Protocol 2: PET/MRI for Synergistic Whole-Body Staging

This hybrid protocol leverages the functional strength of PET and the superior soft-tissue contrast of MRI [7].

- Tracer Administration: Intravenously inject the subject with a PET radiotracer (e.g., 18F-FDG, 68Ga-PSMA). The administered activity for 18F-FDG in human studies is typically 258 ± 50 MBq [7].

- Uptake Period: Allow ~60 minutes for the tracer to distribute and be taken up by target tissues.

- Sequential Imaging: First, acquire a low-dose CT scan for initial anatomical correlation and attenuation correction. This is followed by the PET acquisition. Subsequently, perform the MRI scan on an integrated system. A typical whole-body MRI protocol includes [7]:

- Attenuation Correction Sequence: A coronal 3D Dixon VIBE sequence.

- Anatomical Imaging: Transverse T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences.

- Functional/Diffusion Imaging: Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences to assess tissue cellularity.

- Image Reconstruction and Fusion: Reconstruct PET data using iterative algorithms (e.g., ordered-subset expectation maximization). The MRI-derived attenuation maps are used for accurate PET attenuation correction. Fused PET/MRI images are generated for analysis.

- Interpretation: Images are reviewed in consensus by a radiologist and nuclear medicine physician. Findings are classified, and clinical relevance is assessed.

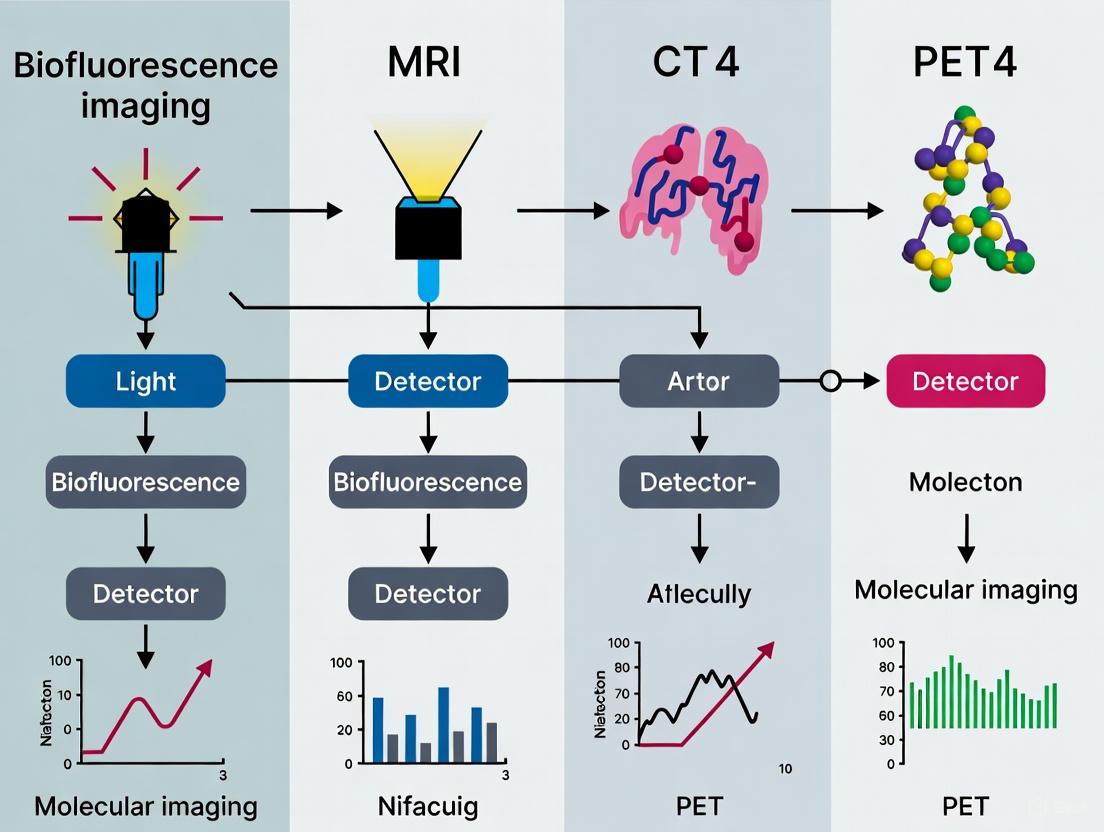

Fundamental Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Bioluminescence vs Fluorescence Mechanism

Diagram 2: PET/MRI Integrated Imaging Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Molecular Imaging

| Item | Function & Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Luciferase Reporters | Genetically encoded enzymes that catalyze light-emitting reactions for BLI [1]. | Firefly luciferase (Fluc), Renilla luciferase (Rluc), Bacterial Lux operon [1]. |

| Luciferin Substrates | Chemical compounds oxidized by luciferases to produce bioluminescent light [1] [2]. | D-luciferin (for Fluc), Coelenterazine (for Rluc and Gaussia luciferase) [1]. |

| Fluorescent Proteins & Dyes | Molecules that absorb external light and re-emit it at a longer wavelength for FLI [2]. | GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein), RFP (Red Fluorescent Protein), Cyanine dyes (Cy5, Cy7) [9]. |

| PET Radiotracers | Radioactive molecules that target specific metabolic pathways or receptors for functional imaging [8]. | 18F-FDG (glucose metabolism), 68Ga-PSMA (prostate cancer), 68Ga-DOTATOC (neuroendocrine tumors) [7] [8]. |

| MRI Contrast Agents | Paramagnetic or superparamagnetic materials that alter tissue relaxation times to enhance contrast [10]. | Gadolinium-based chelates (Gd-DOTA, Gd-DTPA), Manganese-based complexes, Iron oxide nanoparticles [10]. |

| Dual-Modality Probes | Integrated agents designed to provide contrast for two imaging modalities simultaneously [10]. | Small-molecule probes (e.g., Gd-DOTA-4AMP-18F for PET/MRI), Nanoparticle-based probes [10]. |

Molecular imaging is indispensable for biomedical research and drug development, enabling the non-invasive visualization of biological processes. Two dominant technological approaches for this task are biofluorescence imaging and radiation-based modalities like MRI, CT, and PET. Each offers a distinct combination of strengths in resolution, sensitivity, and depth penetration, making the choice of instrumentation critical for experimental design. This guide provides an objective comparison of the hardware underlying these technologies, equipping researchers with the data needed to select the optimal system for their specific research context.

Performance Comparison: Biofluorescence Imaging vs. Anatomical and Nuclear Modalities

The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of key molecular imaging modalities, highlighting their complementary nature.

Table 1: Instrumentation Performance Comparison for Molecular Imaging

| Imaging Modality | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Strength | Primary Limitation | Common Instrumentation & Hardware |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Imaging (NIR-II) | ~μm to mm scale [11] | ~1-10 mm (highly wavelength-dependent) [11] [12] | High sensitivity, real-time imaging, non-radioactive [11] | Limited tissue penetration, scattering, autofluorescence [11] | NIR-sensitive cameras (InGaAs/CCD), lasers, optical filters [12] |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Sub-mm to mm scale [13] | No practical limit (full body) [14] | Excellent soft-tissue contrast, no ionizing radiation [13] | Low sensitivity, high cost, long scan times [14] | Superconducting magnet (1.5T-7T), RF coils, gradient systems [13] |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | Mm scale [11] [15] | No practical limit (full body) [14] | Exceptional sensitivity (picomolar), quantitative metabolic data [16] [15] | Requires radioisotopes, lower resolution, radiation exposure [11] | Gamma photon detectors (BGO, LSO crystals), photomultiplier tubes [17] |

| Computed Tomography (CT) | Sub-mm scale [14] | No practical limit (full body) [14] | High-speed bone and tissue anatomy imaging [14] | Low soft-tissue contrast, ionizing radiation [14] | X-ray tube, rotating gantry, digital detector array [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Acquisition

The performance data in Table 1 is derived from standardized experimental protocols. Below are the methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide, which are essential for understanding the quantitative comparisons.

Protocol 1: High-Contrast In Vivo NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging

This protocol is based on research that explored fluorescence imaging in the 1880-2080 nm window, a region previously avoided due to strong water absorption [12].

- Objective: To achieve high-contrast fluorescence imaging of vasculature in live mice by exploiting the water absorption peak at ~1930 nm.

- Materials:

- Fluorescent Probe: Water-soluble core-shell PbS/CdS quantum dots (QDs) with emission peaks at 1700 nm or beyond [12].

- Imaging System: NIR-sensitive camera (e.g., InGaAs detector) capable of detecting light in the 1880-2080 nm range.

- Animal Model: Live mice (e.g., BALB/c).

- Procedure:

- Synthesize and PEGylate PbS/CdS QDs to ensure water solubility and biocompatibility [12].

- Intravenously administer the QDs into the mouse tail vein.

- Excite the QDs with an 808 nm laser diode.

- Collect emitted fluorescence using the NIR camera through a long-pass filter (>1880 nm).

- Acquire images and analyze the Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) and Structure Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), comparing results to those from traditional NIR-II sub-windows (e.g., 1500-1700 nm) [12].

- Supporting Data: The study demonstrated that the 1880-2080 nm window provides a higher SBR and SSIM compared to the NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm) window, due to enhanced suppression of scattered photons by water absorption [12].

Protocol 2: Integrated PET/MRI for Glioblastoma (GBM) Monitoring

This protocol outlines the methodology for a multimodal imaging study that combined the strengths of PET and MRI for brain tumor assessment [15].

- Objective: To evaluate the complementary value of FLT-PET and contrast-enhanced MRI in diagnosing Glioblastoma (GBM) and assessing early treatment response.

- Materials:

- Scanner: Integrated PET/MRI system (e.g., GE SIGNA PET/MRI).

- PET Tracer: 18F-fluorothymidine (FLT), a marker of cellular proliferation.

- MRI Contrast Agent: Gadolinium-based contrast agent.

- Subjects: Human patients with diagnosed GBM.

- Procedure:

- Patients undergo four sequential FLT-PET/MRI examinations: before and during radiochemotherapy.

- For the PET component, administer FLT intravenously and acquire emission data.

- For the MRI component, acquire T1-weighted images before and after gadolinium injection.

- Reconstruct PET images and correct for attenuation.

- Co-register PET and MRI image sets using advanced analysis platforms (e.g., MATLAB, imlook4d).

- Extract quantitative parameters: from MRI (tumor volume), and from PET (SUVmax, PET tumor volume, Total Lesion Activity - TLA) [15].

- Supporting Data: The study found that while MRI showed significant variations in tumor response between long-term and short-term survivors, PET parameters like SUVmax and TLA provided complementary trending data for predicting progression-free survival [15].

Instrument Workflows and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational principles and data acquisition workflows for fluorescence imaging and a combined PET/MRI system, highlighting their distinct approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of molecular imaging experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details essential components for the featured modalities.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Molecular Imaging

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorophores | Fluorescent probes for deep-tissue imaging. | PbS/CdS Quantum Dots [12]; BODIPY dyes [11]. Emit in 1000-2080 nm range to reduce scattering. |

| Targeted Antibodies | Conjugates for specific molecular targeting. | Trastuzumab (Herceptin) conjugated to Alexa Fluor dyes for HER2+ tumor imaging [11]. |

| PET Radioisotopes | Radiotracers for metabolic and functional imaging. | 18F-fluorothymidine (FLT) for monitoring tumor proliferation [15]. |

| MRI Contrast Agents | Compounds to enhance soft-tissue contrast. | Gadolinium-based complexes [14] [15]; Ultrasmall Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (USPIONs) for multimodal (MRI/SPECT/PET) imaging [16]. |

| FLIM Analysis Software | Tools for analyzing fluorescence lifetime, independent of probe concentration. | FLiSimBA framework for simulating and analyzing FLIM data in biological tissue, accounting for autofluorescence [18]. |

| Quality Control Phantoms | Devices for ensuring scanner performance and quantification accuracy. | ACR-approved PET phantom for semi-annual uniformity, contrast, and resolution testing [17]. |

The choice between biofluorescence imaging and modalities like MRI, CT, and PET is not a matter of selecting a superior technology, but rather the optimal tool for a specific research question. Fluorescence instrumentation (cameras, NIR probes) offers unparalleled capabilities for real-time, high-sensitivity molecular imaging in superficial tissues or in pre-clinical models where radiation is a concern. In contrast, MRI, PET, and CT scanners provide critical anatomical and functional data from deep within the body. As evidenced by the growing development of multimodal probes and integrated systems like PET/MRI, the future of molecular imaging instrumentation lies in strategic combination, leveraging the complementary strengths of each hardware platform to achieve a more comprehensive biological picture.

The Role of Contrast Agents and Fluorophores in Signal Generation

In molecular imaging, the signal generation mechanism is fundamentally determined by the physical and chemical properties of the contrast agent used. These agents interact with specific forms of energy—whether light, magnetic fields, or radiation—to produce detectable signals that reveal biological processes at the cellular and molecular level. Optical imaging, primarily using fluorophores, relies on the absorption and re-emission of light, offering high sensitivity and spatial resolution at superficial depths. In contrast, clinical modalities like MRI, CT, and PET depend on contrasting mechanisms based on magnetic properties, X-ray attenuation, or radioactive decay, respectively, providing greater tissue penetration but often at the cost of molecular specificity or temporal resolution [19] [20] [21]. The choice of imaging agent directly dictates the type of information that can be obtained, from anatomical structure to functional and molecular activity. This guide provides an objective comparison of these agents, their performance characteristics, and the experimental methodologies used to evaluate them, framed within the context of selecting appropriate tools for research and drug development.

Fundamental Signaling Mechanisms

The underlying principles of signal generation differ significantly across imaging modalities. The following diagram illustrates the core pathways for the primary agents discussed in this guide.

The signaling pathways for different classes of contrast agents involve distinct physical processes. Fluorophores, including organic dyes like indocyanine green (ICG) and targeted antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor dyes, absorb high-energy photons and, after a brief period in an excited state, emit lower-energy photons [19] [22]. This Stokes shift allows the emitted light to be distinguished from the excitation light. The resulting signal is detected as fluorescence intensity, which can be quantified and mapped. Conversely, MRI contrast agents, such as gadolinium-based complexes or iron oxide nanoparticles, operate by altering the magnetic relaxation times of water protons in their immediate vicinity [21]. They do not generate a signal themselves but modify the native tissue signal, producing contrast detectable as changes in T1 or T2 relaxation times on an MRI scanner.

PET tracers incorporate positron-emitting isotopes (e.g., ¹⁸F, ⁶⁴Cu). The emitted positron travels a short distance before annihilating with an electron, producing two coincident gamma photons traveling in nearly opposite directions [23]. Detection of these simultaneous photons by a PET scanner ring allows precise localization of the radioactive source. CT contrast agents, typically iodine-based compounds or heavy metal nanoparticles, function by absorbing X-rays more effectively than surrounding tissue [21]. This differential attenuation results in increased signal (measured in Hounsfield Units) on X-ray detectors, effectively mapping tissue density or vascular structures.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The practical utility of an imaging agent is determined by a set of key performance parameters. The table below provides a comparative overview of these characteristics for agents used in different modalities.

Comparison of Contrast Agent Performance Characteristics

| Imaging Modality | Agent Type | Sensitivity | Spatial Resolution | Tissue Penetration | Temporal Resolution | Key Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Imaging | Organic Dyes (e.g., ICG, Alexa Fluor) | High (nM-pM) [24] | Microscopic to Macroscopic (μm-mm) [19] | Limited (mm-cm) [24] | Excellent (Seconds-Minutes) [22] | Fluorescence Intensity, Quantum Yield, Stokes Shift [20] |

| MRI | Gadolinium Complexes, Iron Oxide NPs | Low (μM-mM) [21] | High (10-100 μm) [21] | Unlimited (Whole body) | Slow (Minutes-Hours) | Relaxivity (r1, r2), Contrast-to-Noise Ratio [21] |

| PET | Radiolabeled Tracers (e.g., ¹⁸F-FDG, ⁶⁴Cu-mAb) | Very High (pM-fM) [23] | Low (1-2 mm) [23] | Unlimited (Whole body) | Moderate (Minutes) | Standardized Uptake Value (SUV), % Injected Dose per Gram (%ID/g) [23] |

| CT | Iodinated Compounds, Gold NPs | Low (μM-mM) [21] | High (50-200 μm) [21] | Unlimited (Whole body) | Very Fast (Seconds) | Hounsfield Units (HU), Attenuation Coefficient [21] |

Fluorophores excel in sensitivity and temporal resolution, enabling the detection of low-abundance molecular targets and the monitoring of fast biological processes, but are constrained by limited tissue penetration due to light scattering and absorption [24]. In vivo, their signal is surface-weighted, meaning fluorescence intensity decreases rapidly the deeper a probe is embedded. MRI and CT provide high spatial resolution and unrestricted penetration, offering exquisite anatomical detail, but their contrast agents are typically less sensitive to low concentrations of molecular targets [21]. PET stands out for its exceptional sensitivity and quantitative whole-body capability, allowing for tracer quantification in picomolar to femtomolar concentrations, though with lower spatial resolution than MRI or CT [23].

A critical development is the creation of multimodal agents that combine strengths from different modalities. For example, a single nanoparticle can be tagged with both a radionuclide for PET and a fluorophore for optical imaging [23] [25] [26]. This allows for non-invasive, quantitative whole-body imaging via PET, followed by high-resolution, real-time fluorescence imaging for surgical guidance or histological validation. The stability of the fluorophore compensates for the rapid decay of the PET isotope, enabling longitudinal correlative studies [23].

Experimental Protocols for Agent Evaluation

Rigorous, standardized experimental protocols are essential for the objective comparison of contrast agents. The workflow for evaluating a novel targeted fluorescent agent, common in cancer research, is outlined below.

Protocol 1: Evaluating a Targeted Fluorescent Agent In Vivo

This protocol is designed to assess the specificity, biodistribution, and signal kinetics of a novel fluorescent probe in a preclinical tumor model [19] [22] [24].

1. Probe Synthesis & Characterization: The targeting ligand (e.g., an antibody like trastuzumab or a small peptide like RGD) is chemically conjugated to an organic fluorophore with near-infrared emission (e.g., Alexa Fluor 660, Cy5.5, or IRDye 800CW) [19]. The conjugate is purified, and the degree of labeling (dye-to-protein ratio) is determined spectroscopically. This ensures consistent optical properties and function.

2. In Vitro Cell Validation: Prior to in vivo studies, the probe's binding specificity is validated in cell culture. Target-positive and target-negative cell lines are incubated with the probe. Binding affinity and specificity are quantified using flow cytometry or confocal microscopy, comparing signal intensity between the two cell populations [19].

3. Animal Model Preparation: A relevant disease model, typically a mouse xenograft with a human tumor cell line expressing the target antigen (e.g., EGFR-overexpressing squamous cell carcinoma), is established. Animals are housed and handled according to institutional animal care guidelines.

4. In Vivo Imaging: The probe is administered intravenously via tail vein injection. Animals are imaged at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 24, and 48 hours post-injection) using a fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) system. The animal is placed in the imaging chamber, and a 3D scan is acquired. If a hybrid system is available, a co-registered CT or MRI scan is performed immediately after to provide anatomical context [24]. This allows for longitudinal tracking of probe accumulation and clearance.

5. Ex Vivo Validation: After the final imaging time point, animals are euthanized, and tumors along with major organs (liver, spleen, kidneys, heart, lungs) are harvested. These tissues are imaged ex vivo to quantify the fluorescence signal in each organ. Tissues are then fixed, sectioned, and stained (e.g., with H&E) for histological analysis. Fluorescence microscopy is used to confirm the cellular localization of the probe signal and its co-localization with the target biomarker [19].

6. Data Analysis & Quantification: Fluorescence data is analyzed to calculate key metrics. The Tumor-to-Background Ratio (TBR) is determined by dividing the mean fluorescence intensity of the tumor by the intensity of adjacent normal tissue or muscle. For quantitative comparison, the Percentage of Injected Dose per Gram of tissue (%ID/g) is calculated [19] [23]. Statistical analysis (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) is performed to confirm significant differences in probe uptake.

Protocol 2: Assessing a Multimodal PET/Fluorescence Agent

This protocol highlights the complementary data obtained from a single multimodal probe, combining the quantitative depth penetration of PET with the high-resolution capabilities of fluorescence imaging [23].

1. Agent Preparation: A targeting vector (e.g., an antibody or peptide) is dual-labeled with both a positron-emitting isotope (e.g., ⁶⁴Cu via a chelator like NOTA or DOTA) and a NIR fluorophore (e.g., Alexa Fluor 750) [23]. Radiochemical purity and specific activity are determined before injection.

2. Hybrid Imaging: The dual-labeled agent is injected into tumor-bearing mice. At the time of peak tumor uptake (determined from prior pharmacokinetic studies, e.g., 24 hours for antibodies), a PET scan is acquired. The scan provides whole-body, quantitative data on probe distribution and allows calculation of %ID/g in all organs, leveraging the high sensitivity of PET for deep-tissue lesions [23]. This is followed immediately by a fluorescence imaging session, which may reveal superficial tumor margins and vascular patterns with higher spatial resolution than the PET scan.

3. Data Correlation & Autoradiography: After imaging, animals are euthanized, and tumors are excised and frozen. Tissue sections are prepared. Autoradiography is performed to capture the high-resolution distribution of the radioactive signal within the tumor. The same sections are then imaged with a fluorescence slide scanner. Co-registration of the autoradiography and fluorescence images validates that both labels track the same biodistribution, confirming the probe's integrity and enabling correlation of macroscopic PET data with microscopic fluorescence findings [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key reagents and materials essential for conducting experiments in molecular imaging agent development and evaluation.

Key Reagents for Contrast Agent Research

| Reagent / Material | Core Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Near-Infrared Fluorophores (e.g., Cy5.5, Alexa Fluor 660, IRDye 800CW) | Serves as the optical reporter; absorbs and emits light in the NIR window (650-900 nm) where tissue absorption and autofluorescence are minimal [19] [22]. | Conjugated to antibodies or peptides for targeted tumor imaging in vivo [19]. |

| PET Radionuclides (e.g., ⁶⁴Cu, ⁸⁹Zr, ¹⁸F) | Serves as the radioactive reporter for PET; decays by positron emission, enabling deep-tissue, quantitative imaging [23]. | Radiolabeled to biologics for tracking their biodistribution and pharmacokinetics over time. |

| Bifunctional Chelators (e.g., DOTA, NOTA) | Chemically links radionuclides (like ⁶⁴Cu) to a targeting biomolecule without altering its biological function [23]. | Essential for synthesizing radioimmunoconjugates (e.g., ⁶⁴Cu-DOTA-trastuzumab). |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., mAbs, RGD Peptide, EGF) | Confers molecular specificity by binding to biomarkers overexpressed on target cells (e.g., EGFR, integrins) [19] [21]. | The "homing" component of a targeted contrast agent, driving accumulation at the disease site. |

| Fluorescence Molecular Tomography (FMT) System | Preclinical imaging system that reconstructs 3D quantitative maps of fluorophore concentration in living animals [24]. | Used for longitudinal, quantitative assessment of probe accumulation in tumors. |

| Hybrid Imaging Systems (e.g., FMT-CT, FMT-MRI) | Combines the molecular data from FMT with high-resolution anatomical context from CT or MRI in a single session [24]. | Provides precise anatomical localization of fluorescent signals, improving accuracy. |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | FDA-approved non-targeted NIR fluorescent dye [22]. | Used as a control agent for vascular and perfusion imaging, and for intraoperative guidance. |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) Sense Probe | An activatable fluorescent probe that remains quenched until cleaved by specific enzymes like MMPs [26]. | Used to image enzyme activity (e.g., in tumor microenvironment or neuroinflammation) rather than just target presence. |

Molecular imaging has revolutionized biomedical research and drug development by enabling the non-invasive visualization, characterization, and quantification of biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels within living organisms. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the optimal imaging modality requires careful consideration of key performance parameters, primarily sensitivity, spatial resolution, and penetration depth. These parameters determine a technology's ability to detect molecular targets, precisely locate them, and do so through various tissue depths.

This guide provides a objective, data-driven comparison of two major approaches: optical molecular imaging (specifically biofluorescence imaging) and clinical structural/functional imaging (MRI, CT, and PET). Biofluorescence imaging, including techniques like Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLI) and Fluorescence Molecular Tomography (FMT), offers high sensitivity and specific molecular contrast, but is constrained by photon penetration in tissues. In contrast, MRI, CT, and PET provide superior penetration for whole-body human and preclinical applications, but with varying trade-offs in resolution, sensitivity, and molecular specificity. The following sections will dissect these trade-offs using quantitative data and experimental evidence to inform modality selection for specific research applications.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Parameters

The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of the primary imaging modalities, synthesizing data from comparative studies and technology reviews.

Table 1: Key Parameter Comparison of Molecular Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Sensitivity | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Imaging (FLI) | High (nanomolar to picomolar) [27] | Low to Moderate (∼1-3 mm macroscopic; μm microscopic) [28] [27] | Shallow (∼1-2 cm) [27] | High specificity, non-radiative, low cost, real-time imaging [27] | Shallow penetration, scattering & absorption effects, difficult tomography [27] |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Low (millimolar) [27] | High (∼10-100 μm preclinical; ∼1 mm clinical) [28] [29] [30] | Unlimited (whole-body) | Excellent soft-tissue contrast, anatomical & functional data, no ionizing radiation [27] | Low sensitivity, high cost, long acquisition times [27] |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | Very High (picomolar) [27] | Moderate (∼1-2 mm preclinical; ∼4-7 mm clinical) [28] [31] [32] | Unlimited (whole-body) | Ultra-high sensitivity, absolute quantification, deep-tissue molecular imaging [27] [31] | Ionizing radiation, lower resolution than MRI, cyclotron requirement [27] |

| Computed Tomography (CT) | Not Applicable (anatomical) | High (∼50 μm preclinical; ∼0.5 mm clinical) | Unlimited (whole-body) | High-speed acquisition, excellent bone contrast, high resolution [27] | Low soft-tissue contrast, ionizing radiation, primarily anatomical [27] |

Deep Dive: Experimental Data and Performance Validation

Performance in Tumor Detection and Biodistribution Studies

Direct comparisons in preclinical models provide the most concrete evidence for modality performance. A seminal study compared FLI, PET, MRI, and Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) for monitoring tumor growth in mouse models.

Table 2: Tumor Detection Performance in Preclinical Models [28]

| Imaging Modality | Ability to Detect Small, Non-Palpable Tumors | Performance in Tumor Burden Measurement | Practicality for Longitudinal Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioluminescence (BLI) | Excellent | Excellent | High |

| Fluorescence Imaging (FLI) | Limited (macroscopic tumors only) | Good | High |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | Excellent | Good | Moderate (radiotracer availability) |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Limited (macroscopic tumors only) | Good | Moderate (cost, time) |

The study concluded that while BLI and FDG-PET were capable of identifying small, non-palpable tumors, MRI and FLI could only detect macroscopic, clinically evident tumors [28]. This highlights FLI's primary limitation in sensitivity for very early disease detection compared to radionuclide methods.

In biodistribution assessments, a direct comparison between FMT/CT and PET/MRI for tracking antibody delivery in xenograft models found that both methods faithfully monitored distribution and correlated significantly with ex vivo data [33]. However, the fluorescent label (Alexa750) altered pharmacokinetics, showing shorter blood half-times and higher liver uptake compared to the radiolabeled (64Cu) counterparts [33]. This is a critical consideration for drug development, indicating that the choice of label can influence the biological outcome.

Diagnostic Accuracy in Clinical Applications

The high specificity of PET is evident in clinical studies. A systematic review of 18F-FDG PET/CT for axillary lymph node staging in breast cancer found it has a modest sensitivity of 52.2% but a very high specificity of 91.6% [31]. This high specificity means a positive PET/CT scan is a strong indicator of disease (PPV of 77.8%), though its low sensitivity precludes it from ruling out metastasis alone [31].

Another 2025 study on giant cell arteritis found that combined cranial and large vessel PET/CT had the highest sensitivity (89%) and specificity (98%) compared to ultrasound, MRI, and temporal artery biopsy [34]. This demonstrates PET's power in specific clinical inflammatory conditions.

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols in Focus

Protocol for Depth-Resolved Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLI)

The HSF-FLI (High Spatial Frequency-Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging) protocol addresses FLI's depth challenge using structured illumination [35].

- Aim: To selectively isolate subsurface fluorescence from surface signals while preserving accurate lifetime estimation [35].

- Setup: A time-gated Intensified Charge-Coupled Device (ICCD) camera system with a Digital Micro-mirror Device (DMD) for projecting structured illumination patterns. Excitation is provided by a tunable Ti:sapphire laser [35].

- Procedure:

- Structured Illumination: The sample is illuminated with three-phase sinusoidal patterns at high spatial frequencies projected via the DMD.

- Signal Demodulation: The modulated surface signal (

I_AC) and non-modulated subsurface signal (I_sub) are decomposed from the total fluorescence (I_DC) using phase offset signals [35]. - Lifetime Fitting: Fluorescence decays are acquired over multiple time gates. A bi-exponential model is fitted to the data via Non-linear Least Squares Fitting (NLSF) to recover depth-resolved lifetime maps [35].

- Validation: The method was cross-validated in mouse models bearing tumor xenografts using ex vivo measurements, confirming its ability to separate superficial skin signals from deeper tumor-derived fluorescence [35].

Figure 1: HSF-FLI Experimental Workflow for Depth Resolution

Protocol for Comparative Biodistribution Study (FMT/CT vs. PET/MRI)

This protocol directly compares the quantitative accuracy of optical and nuclear imaging for drug biodistribution [33].

- Aim: To systematically investigate the performance of FMT/CT versus PET/MRI for quantitative analysis of antibody biodistribution in xenografts [33].

- Animal Model: Nude mice with subcutaneously implanted A-431 squamous cell carcinoma tumors [33].

- Probe Preparation:

- FMT/CT: Anti-EGFR antibody formats (mAb, F(ab')2, Fab) labeled with Alexa750 dye.

- PET/MRI: The same antibody formats conjugated with 64Cu-NODAGA radiolabel [33].

- Imaging Protocol:

- Inject labeled compounds intravenously into separate cohorts.

- Image mice at 2 and 24 hours post-injection using both FMT/CT and PET/MRI systems.

- For FMT/CT: Acquire CT for anatomy, then FMT using multiple laser injection points for 3D reconstruction.

- For PET/MRI: Perform a 10-minute PET scan followed by a T2-weighted MRI sequence for anatomical coregistration [33].

- Quantification: Segment regions of interest (tumor, liver, kidney, muscle) on fused images. Compare in vivo imaging data to ex vivo fluorescence, γ-counting, and electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) of explanted organs [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Molecular Imaging Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Genes (e.g., GFP, RFP, Luciferase) | Genetically encoded probes for tracking gene expression, protein localization, and cell fate in vivo [27] [36]. | Engineering stable cell lines for tumor models; creating transgenic reporter animals. |

| Synthetic Fluorophores (e.g., Alexa750) | Fluorescent dyes for labeling antibodies, peptides, and other biomolecules for FLI and FMT [33]. | Labeling therapeutic antibodies for biodistribution and pharmacokinetic studies [33]. |

| Radionuclides (e.g., 18F, 64Cu) | Radioactive isotopes for PET imaging, enabling ultra-sensitive detection of molecular targets [31] [33]. | Synthesizing radiotracers like 18F-FDG for metabolic imaging; labeling antibodies with 64Cu [33]. |

| Structured Illumination Devices (DMD) | Digital Micro-mirror Devices for projecting precise light patterns to enable depth resolution in wide-field fluorescence imaging [35]. | Implementing HSF-FLI to separate surface from subsurface fluorescence signals in macroscopic imaging [35]. |

| Metasurface Enhancement Plates | Thin, smart metamaterials that manipulate radiofrequency fields to locally boost the Signal-to-Noise Ratio in MRI [30]. | Placing on the subject to achieve an up to eightfold SNR increase in 3T MRI without affecting the transmit field [30]. |

Technological Advancements and Future Directions

Pushing the Boundaries of Resolution and Sensitivity

Innovations continue to push the physical limits of each modality. In PET, ongoing development of ultra-high spatial resolution clinical systems targets resolutions below 2 mm, with dedicated organ-specific scanners (e.g., for head/neck or breast) achieving ~1 mm³ resolution through advanced detector materials and readout electronics [32]. In MRI, super-resolution parallel imaging (SURE-SENSE) techniques leverage intra-voxel coil sensitivity variations from multi-channel arrays to reconstruct higher-resolution images from fully-sampled low-resolution data, particularly beneficial for fMRI and spectroscopic imaging [29]. Furthermore, the integration of smart, thin metasurfaces can significantly boost MRI SNR—up to eightfold in 3T systems—by focusing the receive field without the need for bulky hardware, overcoming some fundamental sensitivity constraints [30].

Enhancing Fluorescence Imaging for Deeper Insights

For fluorescence imaging, the development of HSF-FLI represents a significant leap. By coupling structured illumination with physics-based depth modeling, it effectively eliminates surface signal bias without chemical clearing agents, enabling more accurate lifetime readouts from deeper tissues for applications like monitoring antibody-target engagement in tumors [35]. The broader field is also advancing with new bioluminescent and fluorescent probes, including near-infrared agents and quantum dots, which offer improved photon penetration and stability, expanding the possibilities for studying molecular interactions in live animals [27] [36].

Figure 2: Decision Logic for PET/MRI versus FLI/FMT Modalities

The choice between biofluorescence imaging (FLI/FMT) and clinical modalities like MRI, CT, and PET is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with research goals. As the comparative data show, PET remains the gold standard for high-sensitivity, whole-body molecular imaging, despite its use of ionizing radiation. MRI provides unparalleled soft-tissue contrast and high resolution for anatomical and functional studies. Fluorescence imaging offers an exceptional combination of high molecular specificity, safety, and cost-effectiveness, making it ideal for high-throughput preclinical studies, particularly those focusing on superficial tissues or using optical windowing techniques.

Emerging technologies are steadily eroding the traditional limitations of each modality. Ultra-high-resolution PET, super-resolution MRI, and depth-resolved fluorescence imaging are creating a new paradigm where the boundaries of sensitivity, resolution, and penetration depth are continuously being redrawn. For the modern researcher, this evolving landscape offers an expanding toolkit to precisely target complex biological questions in drug development and molecular research.

Practical Applications in Preclinical and Clinical Research

Tracking Tumor Dynamics and Metastasis with Fluorescence and PET

Modern oncology relies heavily on advanced imaging technologies to visualize tumors, track their dynamic changes, and detect metastasis. Among the most powerful tools are optical imaging techniques, particularly fluorescence imaging (FLI), and radionuclide-based techniques like positron emission tomography (PET). These modalities offer complementary insights into the molecular underpinnings of cancer. Fluorescence imaging provides high-resolution, real-time visualization of superficial tumors and precise surgical guidance, leveraging non-ionizing radiation for longitudinal studies [37]. In contrast, PET imaging offers unparalleled sensitivity for deep-tissue metabolic profiling and whole-body metastasis screening, albeit with ionizing radiation [38]. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and experimental protocols of these two pivotal technologies within the broader context of molecular imaging research, providing a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal tool for their specific investigative needs.

Technology Comparison: Fundamental Principles and Performance Metrics

Core Imaging Principles

Fluorescence Imaging (FLI): This technique operates on the principle of light emission from fluorophores. When a fluorescent probe (fluorophore) is excited by light at a specific wavelength, its electrons jump to a higher energy state. As they return to the ground state, they emit light at a longer, lower-energy wavelength. This emitted light is detected to create an image [11] [37]. Its utility in tumor imaging is significantly enhanced by using targeted probes that accumulate in tumors based on specific biomarkers like enzymes, receptor proteins, or the unique tumor microenvironment (e.g., hypoxia, acidosis) [39].

Positron Emission Tomography (PET): PET is a nuclear medicine technique that detects pairs of gamma rays emitted indirectly by a radioactive tracer introduced into the body. The most common tracer is 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG), a glucose analog that is preferentially taken up by highly metabolically active cancer cells via the Warburg effect. The decay of the radionuclide produces positrons, leading to gamma ray emission that is detected by the scanner to create a 3D image of tracer concentration [38]. PET provides metabolic or functional information, often combined with CT (PET/CT) or MRI (PET/MRI) to overlay this data with anatomical context [40] [41] [38].

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of FLI and PET based on current research and clinical data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fluorescence Imaging and PET in Tumor Detection

| Performance Characteristic | Fluorescence Imaging (FLI) | Positron Emission Tomography (PET) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | High (micrometer-level) for superficial tumors [39] | Lower than FLI; improved with hybrid PET/CT or PET/MRI [37] |

| Tissue Penetration Depth | Limited (up to ~1 cm in NIR-I; several cm in NIR-II) [39] [37] | Excellent (whole-body) [38] |

| Sensitivity | High (nanomolar level) [37] | Very High (picomolar level) [37] |

| Metabolic Imaging Capability | Indirect, via targeted probes [39] | Direct, with probes like [18F]FDG [38] |

| Real-Time Imaging | Yes, capability for real-time intraoperative guidance [42] [39] | No |

| Radiation Exposure | Non-ionizing [37] | Ionizing (requires radiotracers) [37] |

| Example Detection Rate | N/A (highly probe-dependent) | 48.28% for brain metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma [43] |

| Key Limitation | Tissue autofluorescence & limited depth [11] [37] | Radiation exposure & lower spatial resolution [37] |

Recent advances have pushed fluorescence imaging into the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm). This spectral region offers reduced light scattering, minimal autofluorescence, and deeper tissue penetration compared to the traditional NIR-I window (700-900 nm), leading to higher resolution and signal-to-background ratios [39]. A key clinical milestone was the use of the FDA-approved dye Indocyanine Green (ICG) for NIR-II fluorescence-guided surgery in patients with liver cancer [39].

For PET, the development of novel tracers beyond [18F]FDG is a major frontier. For instance, 18F-fibroblast activation protein inhibitor (18F-FAPI) PET/CT targets cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. One study reported variable detection rates for brain metastases depending on the primary lung cancer type: 48.28% for adenocarcinoma, 16.67% for large cell carcinoma, and 0% for small cell carcinoma [43]. Furthermore, tracers like 11C-Glutamine and 18F-FSPG are being used in dynamic PET to quantify specific metabolic pathways, such as glutamine uptake suppression in colorectal cancer in response to EGFR inhibitor therapy [44].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for NQO1-Targeted Tumor Imaging with a NIR Fluorescent Probe

This protocol is based on a recent study developing the ZX-CHO probe for identifying colorectal cancer tissues [42].

- Objective: To achieve prolonged, in situ imaging of the tumor biomarker NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1) in human colorectal cancer tissues and mouse models.

- Probe Design: The probe, ZX-CHO, consists of three key moieties:

- A dicyanoisophorone fluorophore that emits in the near-infrared (NIR) region (~590 nm).

- A trimethyl lock quinolone propionic acid (Q3PA) group that acts as a specific recognition and cleavage site for NQO1.

- An aldehyde group that serves as an anchoring site, enabling covalent bonding to amino acid residues of the NQO1 enzyme after the Q3PA group is cleaved. This design ensures the fluorescence signal remains at the reaction site for prolonged imaging.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Synthesis & Validation: The probe is synthesized and its structure is validated via techniques like NMR and mass spectrometry. Its optical properties and reactivity with recombinant NQO1 are confirmed in vitro.

- Cell Imaging: Various cancer cell lines are treated with ZX-CHO. Fluorescence signals are measured over time (e.g., 0-12 hours) to confirm NQO1-specific activation and prolonged signal retention.

- In Vivo Tumor Imaging:

- Animal Model: Mice bearing human colorectal tumor xenografts are used.

- Administration: The ZX-CHO probe is administered intravenously.

- Image Acquisition: Fluorescence images are captured at multiple time points post-injection using a NIR fluorescence imaging system.

- Ex Vivo Tissue Imaging: After in vivo imaging, tumors and major organs are excised and imaged to ex-vivo confirm the specificity of the probe and its ability to delineate tumor margins.

- Key Outcome: The probe successfully provided stable and prolonged fluorescent labeling of NQO1 in tumor tissues, enabling clear visualization of the boundary between tumor and normal tissue.

Diagram 1: NQO1 Probe Activation Workflow

Protocol for Detecting Breast Cancer Metastasis with [18F]FDG PET/CT

This protocol follows standardized guidelines and meta-analysis findings for staging breast cancer [38] [45].

- Objective: To accurately detect and localize distant metastases in patients with breast cancer for staging and treatment planning.

- Tracer: [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG).

- Patient Preparation:

- Fasting: Patients are required to fast for at least 4-6 hours prior to the scan to ensure low blood glucose levels and reduce competitive inhibition of FDG uptake.

- Blood Glucose Check: Blood glucose levels are measured; typically, levels below 150-200 mg/dL are required for the scan to proceed.

- Hydration: Patients are encouraged to be well-hydrated.

- Rest: Patients should avoid strenuous exercise for 24 hours before the scan.

- Image Acquisition:

- Tracer Injection: A standardized dose of [18F]FDG (e.g., 3.7-5.18 MBq/kg) is administered intravenously in a quiet, dimly lit room.

- Uptake Period: The patient rests for approximately 60-90 minutes to allow for tracer uptake and distribution.

- Scanning: The patient is positioned in the PET/CT scanner.

- CT Scan: A low-dose CT scan is performed first for anatomical localization and attenuation correction.

- PET Scan: A whole-body PET scan is immediately performed following the CT. The emission data from the PET scan is reconstructed using iterative algorithms and fused with the CT images.

- Image Analysis:

- Qualitative: Fused PET/CT images are visually assessed by a nuclear medicine physician. Areas of focally increased FDG uptake that are not explainable by normal physiology are considered suspicious for malignancy.

- Quantitative: The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) is calculated for identified lesions. SUVmax is a semi-quantitative measure of the tracer concentration within the lesion, providing an index of metabolic activity.

- Performance Data: A 2025 meta-analysis concluded that for detecting distant metastases in breast cancer, [18F]FDG PET/CT demonstrates a pooled sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 95%, performance comparable to the more expensive [18F]FDG PET/MRI [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Fluorescence and PET Imaging Research

| Item Name | Category | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| NQO1 Probe ZX-CHO [42] | Fluorescent Probe | Targets and covalently binds to NQO1 enzyme for in situ tumor imaging | Delineating margins of colorectal cancer in vivo and ex vivo |

| NIR-II Organic Fluorophores [39] | Fluorescent Probe | Emits light in 1000-1700 nm range for deep-tissue, high-contrast imaging | High-resolution imaging of tumor vasculature and metastasis in animal models |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) [11] [39] | Fluorescent Dye | FDA-approved NIR-I dye; used for perfusion and lymphatic mapping | NIR-II fluorescence-guided surgery for liver cancer [39] |

| [18F]FDG [38] [45] | PET Radiotracer | Glucose analog for imaging heightened glycolytic metabolism in tumors | Whole-body staging and detection of metastases in breast cancer |

| 18F-FAPI [43] | PET Radiotracer | Fibroblast activation protein inhibitor; targets tumor stroma | Detecting metastases in adenocarcinomas (e.g., lung, breast) |

| 11C-Glutamine / 18F-FSPG [44] | PET Radiotracer | Probes for glutamine metabolism pathway | Quantifying tumor metabolic response to targeted therapy (e.g., EGFR inhibitors) |

| D-Luciferin [37] | Bioluminescence Substrate | Substrate for firefly luciferase enzyme in bioluminescence imaging | Longitudinal tracking of tumor growth and response in luciferase-expressing xenografts |

Integrated Workflow and Data Analysis

Modern imaging research often involves complex workflows that integrate multiple techniques. The diagram below illustrates a potential integrated pipeline for evaluating a novel therapeutic agent, combining both fluorescence and PET imaging.

Diagram 2: Multimodal Therapy Assessment Workflow

Data Analysis Techniques:

- FLI Data: Analysis involves quantifying fluorescence intensity over time and region of interest (ROI). For the ZX-CHO probe, a key metric is the prolonged retention of signal within the tumor, confirming successful covalent binding [42].

- PET Data: Standardized Uptake Value (SUV), particularly SUVmax, is the primary quantitative metric. In dynamic PET studies, as with 11C-Glutamine, time-activity curves are fitted to multicompartment models to calculate metabolic flux rates (KGLN), providing a more nuanced view of tumor metabolism than a static SUV [44].

- Multimodal Fusion: Software platforms (e.g., MATLAB, imlook4d) are used to co-register and analyze fused datasets, such as FLT-PET and gadolinium-enhanced MRI for glioblastoma, to extract complementary attributes from each modality [41].

The choice between fluorescence imaging and PET for tracking tumor dynamics and metastasis is not a matter of superiority but of strategic application. Fluorescence imaging, particularly with advances in NIR-II probes and covalent targeting strategies, excels in providing high-resolution, real-time molecular data for superficial tumors, longitudinal studies in animal models, and intraoperative guidance. Its limitations in penetration depth are being actively addressed by chemical engineering of novel probes. PET imaging remains the gold standard for clinical whole-body staging, deep-tissue metabolic profiling, and quantitative assessment of therapy response, despite its lower resolution and use of ionizing radiation. The most powerful approach for comprehensive oncological research lies in a multimodal strategy, leveraging the unique strengths of each technology to build a complete picture of tumor biology, from initial molecular changes to systemic metastatic spread.

Visualizing Cellular Metabolism and Gene Expression

Visualizing cellular metabolism and gene expression is fundamental to advancing our understanding of basic biology, disease progression, and therapeutic efficacy. Molecular imaging technologies allow researchers to observe these dynamic processes in living organisms non-invasively and in real time. The field is broadly divided into techniques that provide anatomical and metabolic information, such as MRI, CT, and PET, and those based on optical signals, primarily biofluorescence and bioluminescence imaging [28] [1]. Each modality offers a unique set of capabilities and limitations regarding sensitivity, resolution, depth penetration, and practicality. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these technologies, focusing on their application in visualizing gene expression and metabolic activity, to help researchers select the optimal tool for their specific experimental needs.

Core Technology Comparison

The fundamental principles of these imaging modalities dictate their respective applications in research.

Optical Imaging (Bioluminescence & Fluorescence): These methods are used primarily for visualizing molecular and cellular processes, such as gene expression and protein localization.

- Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) generates light through an enzymatic reaction, typically involving a luciferase enzyme and its substrate (e.g., luciferin). This reaction produces light without the need for external excitation, resulting in a very low background signal and a high signal-to-noise ratio [1] [2].

- Fluorescence Imaging (FLI) requires an external light source to excite a fluorophore, which then emits light at a longer wavelength. While it can produce bright signals and is excellent for multiplexing, it can be affected by background autofluorescence from cells or media [46] [2] [47].

Positron Emission Tomography (PET): A nuclear medicine technique that uses radioactive tracers (e.g., FDG) to visualize metabolic activity. It is highly sensitive and quantitative, allowing for the tracking of processes like glucose metabolism in deep tissues, but requires the use of radioisotopes [28] [48].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Utilizes strong magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed anatomical images. Functional and molecular information can be obtained with targeted contrast agents. MRI provides excellent soft-tissue contrast and spatial resolution without ionizing radiation but generally has lower sensitivity for detecting molecular targets compared to optical or nuclear techniques [28] [49] [50].

Computed Tomography (CT): Employs X-rays to generate high-resolution 3D anatomical images. It is often used in combination with functional modalities like PET (PET/CT) to provide an anatomical reference for the functional data [50] [33].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principles of these key imaging modalities.

Performance Data and Experimental Evidence

Direct, side-by-side comparisons in preclinical models provide the most valuable data for evaluating performance.

Comparative Study on Tumor Model Detection

A 2011 study directly compared FDG-PET, MRI, BLI, and FLI for monitoring tumor growth in mouse models [28]. The key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance comparison of imaging modalities for detecting tumors in mouse models [28].

| Imaging Modality | Able to Detect Non-Palpable/Microscopic Tumors? | Practicality for Longitudinal Studies | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioluminescence (BLI) | Yes | High | Most practical; high sensitivity for small tumors; low background |

| FDG-PET | Yes | Medium | High sensitivity for small tumors; provides metabolic data |

| Fluorescence (FLI) | No (only macroscopic tumors) | High | Practical; useful for superficial and macroscopic tumors |

| MRI | No (only macroscopic tumors) | Low | High anatomical detail; good for spontaneous tumor identification |

This study demonstrated that BLI and FDG-PET were capable of identifying small, non-palpable tumors, while MRI and FLI were only able to detect larger, macroscopic tumors [28]. In terms of practicality for longitudinal studies, optical methods (BLI and FLI) were ranked highest.

Sensitivity in Clinical Staging

A 2025 meta-analysis comparing MRI, FDG-PET/CT, and FDG-PET/MRI for the initial staging of multiple myeloma provides insight into their performance in a clinical diagnostic context [49].

Table 2: Meta-analysis of imaging modalities for initial staging of multiple myeloma [49].

| Imaging Modality | Pooled Sensitivity for Lesion Detection | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Body MRI (WB-MRI) | 0.920 (92.0%) | Superior sensitivity for initial staging |

| Spine/Pelvis MRI | 0.906 (90.6%) | High sensitivity, but limited field of view |

| [^18F]FDG-PET/CT | 0.807 (80.7%) | Lower sensitivity compared to MRI |

The analysis concluded that MRI demonstrated superior sensitivity compared to FDG-PET/CT, leading the authors to suggest that future guidelines might prioritize MRI and FDG-PET/MRI for staging multiple myeloma patients [49].

Quantitative Biodistribution Assessment

A 2018 study systematically compared Fluorescence-Mediated Tomography combined with CT (FMT/CT) and PET/MRI for quantitatively assessing the biodistribution of antibody formats in xenograft models [33]. The experimental protocol involved labeling monoclonal antibodies and their fragments with either a fluorescent dye (Alexa750) for FMT/CT or a radioactive isotope (64Cu) for PET/MRI. Mice were imaged at 2 and 24 hours post-injection.

Both FMT/CT and PET/MRI successfully monitored the biodistribution and elimination routes of the antibody constructs, and the in vivo data from both modalities correlated significantly with ex vivo measurements [33]. However, a critical finding was that the Alexa750 fluorescent label altered the pharmacokinetics of the antibodies, leading to shorter blood half-lives and higher liver uptake compared to the radiolabeled counterparts. This highlights that the choice of label itself can influence the biological process being studied, a key consideration for experimental design.

The workflow of this comparative experiment is detailed below.

Practical Implementation and Reagent Solutions

Choosing the right reagents is paramount to a successful molecular imaging experiment. The table below details key tools for optical and radionuclide-based imaging.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for molecular imaging experiments [28] [1] [2].

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase (Fluc) | Enzyme that catalyzes light emission from D-luciferin. | Reporter for gene expression, cell tracking, and tumor growth in BLI [1]. |

| D-Luciferin | Substrate for Firefly Luciferase. | Administered to animals to produce bioluminescent signal for Fluc-based assays [28]. |

| Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., DsRed2, GFP) | Genetically encoded proteins that fluoresce when excited by external light. | Cell labeling, tracking migration, and reporting gene expression in FLI [28] [2]. |

| Synthetic Fluorophores (e.g., Alexa750) | Synthetic dyes that can be conjugated to antibodies or other targeting molecules. | Targeted imaging of specific biomarkers (e.g., EGFR) in FLI and FMT [33]. |

| ²-deoxy-2-[¹⁸F]fluoro-D-glucose ([¹⁸F]FDG) | Radioactive glucose analog used as a tracer for PET. | Assessing metabolic activity in tissues, such as tumor glucose uptake [28] [48]. |

| ⁶⁴Cu-NODAGA | Radioactive chelator complex for labeling biomolecules. | Enables tracking of biodistribution for compounds like antibodies using PET [33]. |

Side-by-Side Modality Comparison

The choice of imaging technology involves trade-offs. The following table provides a consolidated overview of the core characteristics of each modality to guide selection.

Table 4: Comprehensive comparison of molecular imaging modalities for research.

| Feature | Bioluminescence (BLI) | Fluorescence (FLI) | PET | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Mechanism | Enzymatic reaction [2] | External excitation [2] | Radioactive decay [48] | Magnetic fields/radio waves [50] |

| Sensitivity | Very High [2] | High (but limited by background) [2] | Very High [48] | Low to Moderate [49] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (millimeters) [1] | Moderate (micrometers to millimeters) [46] | Moderate (millimeters) [48] | Very High (sub-millimeter) [50] |

| Tissue Penetration Depth | Limited (1-2 cm) [1] | Limited (depends on wavelength) [46] | Unlimited (whole body) [48] | Unlimited (whole body) [50] |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative | Semi-quantitative | Excellent (fully quantitative) | Semi-quantitative |

| Background Signal | Very Low [2] | Moderate (autofluorescence) [2] | Low | Low |

| Ionizing Radiation | No | No | Yes | No |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity, low background, cost-effective [28] [2] | Multiplexing, real-time imaging [2] | High sensitivity, quantitative, whole-body [28] [48] | Excellent anatomical detail, no radiation [49] [50] |

| Primary Limitation | Requires genetic modification, low penetration [1] | Photobleaching, tissue autofluorescence [46] | Radiation exposure, cost, low resolution [48] | Low molecular sensitivity, high cost, long scan times [49] |

No single molecular imaging modality is universally superior; each serves a distinct purpose in the researcher's toolkit. Bioluminescence imaging excels in high-sensitivity, low-background longitudinal studies of pre-labeled cells and genetic activity in small animals. Fluorescence imaging is ideal for multiplexed experiments and high-resolution spatial visualization of molecular targets, particularly at superficial depths. PET offers unparalleled sensitivity and quantitative capability for tracking metabolic processes and biodistribution throughout the entire body, while MRI provides the highest anatomical soft-tissue contrast for pinpointing lesion locations.

The future of visualizing cellular metabolism and gene expression lies in multimodal imaging and technological integration. Combining modalities like PET/MRI or FMT/CT merges their strengths, providing both functional and high-resolution anatomical information in a single session [50] [33]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) is enhancing image analysis, enabling the extraction of subtle patterns and improving diagnostic accuracy [50]. Continued development of more sensitive, specific, and biocompatible probes will further push the boundaries of what we can visualize, solidifying molecular imaging's central role in biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Image-Guided Surgery and Therapeutic Monitoring

Image-guided surgery and therapeutic monitoring are critical components of modern precision medicine, enabling clinicians to visualize molecular processes in real-time, delineate tumor margins, and assess treatment efficacy. Central to these fields are two overarching classes of molecular imaging technologies: biofluorescence imaging (including techniques like fluorescence-mediated tomography or FMT) and radionuclide/anatomical hybrid imaging (such as MRI, CT, and PET). Biofluorescence imaging offers high spatial resolution and the potential for real-time visualization without ionizing radiation, making it attractive for surgical guidance. In contrast, established modalities like PET and MRI provide superior tissue penetration and whole-body quantitative biodistribution data, which are invaluable for therapeutic monitoring. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and limitations of these technologies for researchers and drug development professionals, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of their complementary roles in molecular imaging research.

Technology Comparison: Biofluorescence Imaging vs. Radionuclide/Anatomical Modalities

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of these imaging modalities based on current technological capabilities.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Molecular Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Key Principle | Spatial Resolution | Tissue Penetration Depth | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Imaging (e.g., FMT) | Detection of light emitted by fluorescent probes (e.g., Alexa750) [33] | ~1-3 mm (FMT/CT) [33] | Superficial (a few mm to cm) | Non-radioactive; real-time imaging; high sensitivity for superficial structures; lower cost [11] | Limited penetration; background autofluorescence; photobleaching; signal quantification affected by tissue optics [11] |

| Super-Resolution Fluorescence (e.g., SPI) | Nanoscale photon reassignment and computational processing [51] | ~116-152 nm (sub-diffraction limit) [51] | Limited to samples/specimens (microscopy) | Extremely high resolution; enables high-throughput subcellular imaging [51] | Not for deep-tissue in vivo imaging; primarily for ex vivo or microscopic analysis |

| PET | Detection of gamma rays from radiotracers (e.g., [18F]FDG, 64Cu) [52] | 1-2 mm (preclinical); 4-7 mm (clinical) | Whole-body | High sensitivity; absolute quantification; whole-body biodistribution data [52] | Use of radioisotopes; lower spatial resolution than MRI; limited anatomical context without hybrid systems |

| MRI | Detection of radiofrequency signals from protons in a magnetic field [15] | 50-500 µm (preclinical); 1-2 mm (clinical) | Whole-body | Excellent soft-tissue contrast; no ionizing radiation; functional and anatomical data [15] | Lower sensitivity than PET/optical; relatively slow imaging; high cost |

| Hybrid PET/MRI | Combination of PET and MRI in a single session [15] | PET: 4-7 mm; MRI: 1-2 mm (clinical) | Whole-body | Simultaneous metabolic/functional and high-contrast anatomical data; superior soft-tissue characterization [52] [15] | Very high cost; complex logistics and data processing; access is limited |

Quantitative Performance Data in Preclinical and Clinical Settings

Direct comparisons of these technologies in standardized settings provide crucial data for informed decision-making.

Diagnostic Accuracy in Clinical Oncology

A 2025 meta-analysis directly compared [18F]FDG PET/CT and [18F]FDG PET/MRI for detecting breast cancer recurrence, providing high-level evidence of their clinical performance [52].

Table 2: Diagnostic Accuracy for Breast Cancer Recurrence (Patient-Level Analysis) [52]

| Imaging Modality | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Statistical Significance (vs. PET/CT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [18F]FDG PET/CT | 0.93 (0.88–0.96) | 0.87 (0.80–0.93) | (Reference) |

| [18F]FDG PET/MRI | 0.99 (0.94–1.00) | 0.98 (0.90–1.00) | Sensitivity: p=0.07; Specificity: p=0.06 |

The study concluded that while PET/MRI showed a trend towards higher sensitivity and specificity, the differences were not statistically significant, highlighting their comparable diagnostic performance for this indication [52].

Preclinical Biodistribution Assessment

A seminal 2018 study directly compared the accuracy of FMT/CT and PET/MRI for assessing the biodistribution of antibody formats in squamous cell carcinoma xenografts, offering a robust preclinical performance comparison [33].

Table 3: Preclinical Performance in Quantifying Antibody Biodistribution [33]

| Performance Metric | FMT/CT (Alexa750 Label) | PET/MRI (64Cu Label) | Correlation & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organ Accumulation Correlation | Significantly correlated with ex vivo measurements | Significantly correlated with ex vivo measurements | Both methods faithfully monitored biodistribution and elimination. |

| Inter-Modality Correlation | Accumulation in kidney, muscle, and tumor correlated with PET/MRI data. | Accumulation in kidney, muscle, and tumor correlated with FMT/CT data. | Supported reliable cross-modality validation. |

| Impact of Label | Shorter blood half-life and higher liver uptake for Alexa750-labeled mAbs. | Different pharmacokinetic profile for 64Cu-labeled mAbs. | Alexa750 labeling altered pharmacokinetics, a critical consideration for preclinical drug research. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide insight into the data generation process, here are the detailed methodologies from the key studies cited.

This protocol outlines a direct comparative imaging study in a preclinical xenograft model.

- Animal Model: Female athymic nude mice bearing subcutaneous A-431 (EGFR-expressing) squamous cell carcinoma tumors (~100 mm³).

- Therapeutic Compounds: Three formats of an anti-EGFR antibody: full-length monoclonal antibody (mAb), F(ab′)2 fragment, and Fab fragment.

- Labeling:

- For FMT/CT: Compounds were labeled with the fluorescent dye Alexa750.

- For PET/MRI: Compounds were conjugated with the chelator NODAGA and radiolabeled with ⁶⁴Cu.

- Dosing: Intravenous tail vein injection of equimolar amounts.

- Imaging Timeline: Scans were performed at 2 hours and 24 hours post-injection.

- FMT/CT Imaging:

- Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane.

- CT Scan: High-resolution protocol (180s scan) for anatomical reference.

- FMT Scan: Approximately 100 laser injection points (745 nm) were applied for 3D fluorescence data acquisition.

- Data Fusion & Quantification: FMT and CT datasets were fused. Fluorescence was reconstructed using heterogeneous absorption and scattering maps derived from CT. Organs and tumors were segmented using CT data, and fluorescence concentration was quantified.

- PET/MRI Imaging:

- Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane.

- PET Scan: 10-minute acquisition on a small-animal PET scanner.

- MRI Scan: Immediately after PET, using a 7T MRI scanner with a T2-weighted 3D turbo-RARE sequence.

- Data Analysis: PET and MRI datasets were co-registered. PET data were normalized, and regions of interest (tumor, liver, kidney, muscle) were segmented for quantification.

- Ex Vivo Validation: After final imaging, blood samples were taken, and organs were harvested for ex vivo fluorescence measurement, γ-counting, and electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) to validate in vivo data.

This protocol describes a high-throughput, real-time super-resolution fluorescence technique for cellular analysis.

- System Setup: Built on an epi-fluorescence microscope (e.g., Nikon Eclipse Ti2-U) with a 100×, 1.45 NA oil objective.

- Core Technology: Incorporates concentrically aligned microlens arrays in illumination and detection paths to contract the point-spread function (PSF).

- Image Acquisition:

- Multifocal Optical Rescaling: Enhances resolution by a factor of √2.

- High-Content Sample Sweeping: Physical translation of the sample for large-area imaging.

- Synchronized TDI Readout: A time-delay integration sensor synchronizes line-scan readout with sample motion, enabling continuous, high-speed data acquisition.

- Image Processing:

- Instant Image Formation: The TDI readout generates sub-diffraction-limited images on the fly.

- Non-Iterative Deconvolution: Optional rapid Wiener-Butterworth (WB) deconvolution provides an additional √2 enhancement, achieving a full 2× resolution improvement over conventional wide-field microscopy.

- Validation: Performance is validated using fluorescent point emitters (to measure PSF) and various biological specimens (e.g., β-tubulin, mitochondria, peripheral blood smears).

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for the key experimental and application pathways described.

Preclinical Biodistribution Study Workflow

Decision Pathway for Imaging Modality Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials used in the featured experiments, highlighting their critical role in generating reliable molecular imaging data.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Alexa750 Dye | Near-infrared fluorescent label for optical imaging. | Labeling antibodies for FMT/CT biodistribution studies [33]. |

| ⁶⁴Cu-NODAGA | Radiometal-chelate complex for PET radiolabeling. | Radiolabeling antibodies for quantitative PET/MRI biodistribution [33]. |

| ⁶⁸Ga-PSMA-11 | PET radiotracer targeting Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen. | Detecting brain metastases from various tumors, offering high tumor-to-background contrast [53]. |

| [¹⁸F]FDG ([¹⁸F]Fluorodeoxyglucose) | PET radiotracer for imaging glucose metabolism. | Standard clinical tool for detecting cancer recurrence in modalities like PET/CT and PET/MRI [52]. |

| BODIPY Dyes | Versatile synthetic fluorophore with high quantum yield and photostability. | Fluorescent probes for cellular imaging; can be modified with targeting moieties (e.g., folic acid) for targeted cancer imaging [11]. |

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin) | Monoclonal antibody targeting HER2 receptor. | Can be conjugated to fluorescent dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor) or radiolabels to visualize HER2+ tumors [11]. |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | Near-infrared fluorescent dye approved for clinical use. | Used in angiography and for real-time visualization of tumors and inflammation during surgery [11]. |

| Anti-EGFR Antibody Formats | Targeting agent for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. | Used as mAb, F(ab′)2, and Fab fragments to study the impact of molecule size on biodistribution in xenograft models [33]. |