Multiplexed Fluorescence Imaging: A Guide to High-Plex Biomarker Analysis for Drug Development and Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern multiplexed fluorescence imaging, a transformative technology enabling the simultaneous visualization of numerous biomarkers within their native tissue context.

Multiplexed Fluorescence Imaging: A Guide to High-Plex Biomarker Analysis for Drug Development and Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern multiplexed fluorescence imaging, a transformative technology enabling the simultaneous visualization of numerous biomarkers within their native tissue context. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of fluorophores and imaging techniques, including novel time-resolved fluorescent proteins and cyclic immunofluorescence. The piece delves into cutting-edge methodological applications in spatial biology and clinical tumor immunology, offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing protocols and conjugation chemistries, and concludes with a comparative analysis of leading platforms to guide technology selection. By synthesizing recent advances, this review serves as a strategic resource for leveraging high-plex imaging to unravel complex biological systems and enhance therapeutic development.

Core Principles and Emerging Fluorophores in Multiplexed Imaging

Fluorescence forms the cornerstone of modern biological research and drug development, enabling the visualization and quantification of biomolecules in living systems with exquisite sensitivity and specificity [1] [2]. The fundamental photophysical process—where a fluorophore absorbs high-energy light and emits lower-energy light—provides a powerful mechanism for probing cellular environments, tracking therapeutic compounds, and understanding complex biological interactions [3] [2]. For researchers investigating complex biological systems, the ability to simultaneously track multiple targets through multiplexed fluorescence imaging has become increasingly vital [4] [5]. This application note details the core principles of fluorescence, quantitative parameters researchers must control, and advanced methodologies for successful multiplexed experiments, providing a foundational framework for applying these techniques in pharmaceutical development and basic research.

The Fluorescence Process: A Photophysical Journey

The fluorescence process occurs through a precise sequence of photophysical events that transform absorbed light into emitted light, typically represented by a Jablonski energy diagram [2].

The fluorescence cycle comprises three essential stages. In Stage 1 (Excitation), a photon of energy (hνEX) from an external source such as a laser or lamp is absorbed by the fluorophore, creating an excited electronic singlet state (S'1) [2]. This process distinguishes fluorescence from chemiluminescence, where the excited state is populated chemically rather than by light absorption [2].

During Stage 2 (Excited-State Lifetime), the excited state exists for a finite time (typically 1-10 nanoseconds), where the fluorophore undergoes conformational changes and interacts with its molecular environment. These interactions cause partial energy dissipation, yielding a relaxed singlet excited state (S1) from which fluorescence emission originates. Not all excited molecules return to the ground state via fluorescence; other processes like collisional quenching, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), and intersystem crossing may also depopulate S1 [2].

In Stage 3 (Fluorescence Emission), a photon of energy (hνEM) is emitted, returning the fluorophore to its ground state S0. Due to energy dissipation during the excited-state lifetime, this emitted photon has lower energy and longer wavelength than the excitation photon. This energy difference, known as the Stokes shift, is fundamental to fluorescence sensitivity as it allows emission photons to be detected against a low background, isolated from excitation photons [3] [2].

Visualizing the Process: Jablonski Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the energy transitions during fluorescence, including vibrational relaxation, fluorescence emission, and competing processes like non-radiative decay and intersystem crossing.

Diagram 1: Jablonski energy diagram illustrating the photophysical processes in fluorescence, including excitation, vibrational relaxation, fluorescence emission, and competing pathways.

Quantitative Parameters in Fluorescence Spectroscopy

The utility of fluorophores in research applications depends on several key quantitative parameters that determine their brightness, stability, and detectability in biological systems.

Core Photophysical Properties

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Fluorescent Dyes [2]

| Property | Definition | Significance in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Extinction Coefficient (EC) | Capacity for light absorption at a specific wavelength (units: cm⁻¹ M⁻¹) | Fluorescence brightness per fluorophore is proportional to EC × Quantum Yield |

| Fluorescence Quantum Yield (QY) | Number of fluorescence photons emitted per excitation photon absorbed | Determines fluorophore efficiency; values range from 0.1-0.9 for commercial dyes |

| Excitation Spectrum | Plot of excitation wavelength vs. number of fluorescence photons generated | Identifies optimal excitation wavelengths for maximum signal output |

| Emission Spectrum | Plot of emission wavelength vs. number of fluorescence photons generated | Enables spectral discrimination for multiplex detection and background reduction |

| Stokes Shift | Energy/wavelength difference between excitation and emission maxima | Allows emission isolation from excitation light, fundamental to detection sensitivity |

| Photobleaching | Irreversible destruction of excited fluorophores due to reactive oxygen species | Limits observation time; depends on exposure duration and intensity |

These parameters collectively determine a fluorophore's effectiveness in specific applications. For instance, the brightness of a fluorophore—which determines its detectability—is calculated as the product of its extinction coefficient and quantum yield [2]. Environmental factors including solvent viscosity, ionic concentrations, pH, and hydrophobicity can profoundly affect both fluorescence intensity and excited-state lifetime [3].

Representative Fluorophore Properties

Table 2: Experimental Quantum Yields of Selected Fluorophores [3]

| Compound | Solvent | Excitation Wavelength (nm) | Emission Wavelength (nm) | Quantum Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acridine Orange | Ethanol | 493 | 535 | 0.46 |

| Benzene | Ethanol | 248 | 300-350 | 0.04 |

| Chlorophyll-A | Ethanol | 440 | 685 | 0.23 |

| Eosin | Water | 521 | 544 | 0.16 |

| Fluorescein | Water | 437 | 515 | 0.92 |

| Rhodamine-B | Ethanol | 555 | 627 | 0.97 |

The data in Table 2 illustrates the substantial variation in quantum yields across different fluorophores, with Rhodamine-B and Fluorescein exhibiting particularly high efficiency. This makes them valuable for applications requiring high signal-to-background ratios. When designing experiments, researchers should note that quantum yields below 1 result from energy loss through non-radiative pathways like heat or photochemical reactions, rather than the re-radiative pathway of fluorescence [3].

Multiplexed Fluorescence Imaging: Challenges and Advanced Solutions

Multiplexed fluorescence imaging—using multiple fluorescent dyes to examine various elements within a sample—has become essential for characterizing complex biological processes and disease states [5]. However, implementing effective multiplexing strategies presents significant technical challenges that require sophisticated solutions.

The Spectral Overlap Challenge

A primary obstacle in multiplexed imaging is signal crosstalk caused by the broad emission spectra of most fluorophores [5]. When using two or more fluorophores, their emission spectra frequently overlap, causing signals to bleed into detection channels intended for other fluorophores. This can yield false positives or negatives and otherwise obscure data if not properly accounted for [5].

Traditional approaches to minimize crosstalk involve careful selection of fluorophore combinations with minimal spectral overlap and using optical filters with restricted bandpasses centered around peak emission wavelengths of individual fluorophores [5]. However, these approaches involve trade-offs—narrow filter bandwidths provide higher specificity but discard more of the desired signal, reducing detection efficiency [5].

Advanced Unmixing Methodologies

To overcome spectral overlap limitations, researchers have developed several computational unmixing techniques:

PICASSO (Process of ultra-multiplexed Imaging of biomoleCules viA the unmixing of the Signals of Spectrally Overlapping fluorophores) enables more than 15-color imaging of spatially overlapping proteins in a single imaging round without using reference emission spectra [4]. This blind unmixing approach uses information theory, iteratively minimizing mutual information between mixed images based on the principle that spectral mixing increases mutual information between channels [4]. PICASSO requires only an equal number of images and fluorophores, making it compatible with standard bandpass filter-based microscopy systems [4].

Bleaching-Assisted Multichannel Microscopy (BAMM) leverages photobleaching behavior as an identifying property, discriminating between fluorescent species by their characteristic photobleaching rates [6]. This approach uses non-negative matrix factorization to extract spectral and photobleaching characteristics from timelapse data of sample bleaching, potentially tripling multiplexing capabilities without additional hardware [6].

Phasor-based analysis provides a powerful method for unmixing multiple fluorophores without reference spectra by transforming spectral data into phasor plots for rapid separation of signals [5]. This approach simplifies workflow by eliminating extensive calibration needs and can separate background autofluorescence from specific signals [5].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for multiplexed fluorescence imaging, incorporating both sample preparation and computational unmixing steps.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for multiplexed fluorescence imaging, showing sample preparation and computational unmixing steps with algorithm options.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: PICASSO for Ultra-multiplexed Imaging

This protocol enables 15-color multiplexed imaging of spatially overlapping proteins in a single staining and imaging round, adapted from the PICASSO methodology [4].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials Table 3: Essential Materials for PICASSO Multiplexed Imaging

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Spectrally overlapping fluorophores | Must be excitable by the same laser source; select from commercial organic dyes |

| Primary antibodies | Target proteins of interest; from same host species permitted |

| Fab fragments of secondary antibodies | Conjugated to fluorophores; form complexes with primary antibodies |

| Assembly buffer | Compatible with antibody-Fab complex formation |

| Mounting medium | Preserves sample integrity during imaging |

| Reference standards | For calibrating fluorescence measurements between experiments |

Procedure

Fluorophore Selection: Choose 15+ spectrally overlapping fluorophores that can be strongly excited by the same laser source. Include large Stokes shift fluorophores to enhance multiplexing capability [4].

Antibody Complex Formation: Use primary antibody-Fab complex preformation technique to bypass host species limitations [4]:

- Assemble each primary antibody with Fab fragment of secondary antibody bearing specific fluorophore

- Combine all assembled antibody complexes together

Sample Staining:

- Apply the mixture of antibody complexes to specimen simultaneously

- Incubate according to standard immunohistochemistry protocols

- Wash to remove unbound complexes

Image Acquisition:

- Acquire images at different spectral ranges, each containing emission peak of specific fluorophore

- Use standard bandpass filter-based microscopy system

- Ensure number of acquired image channels equals number of fluorophores used

Computational Unmixing with PICASSO:

- Initialize channel solutions as acquired mixed images

- Iteratively update solutions by minimizing mutual information between channels

- Apply non-negativity constraints to ensure physically plausible results

- Continue iterations until convergence criteria met (minimal change in mutual information)

Validation:

- Verify unmixing accuracy through control samples with known staining patterns

- Compare with sequential staining results if available

Technical Notes: PICASSO performs particularly well in highly heterogeneous specimens like brain tissue where emission spectra show significant regional variation [4]. The algorithm's effectiveness stems from the assumption that spatial distribution of different proteins is mutually exclusive, enabling accurate information unmixing through mutual information minimization [4].

Protocol: BAMM (Bleaching-Assisted Multichannel Microscopy)

This protocol uses photobleaching characteristics to distinguish fluorescent labels, enabling resolution of up to three fluorescent labels in a single spectral channel [6].

Procedure

Sample Preparation: Label cellular targets with fluorescent species showing distinct photobleaching characteristics, even with similar emission spectra.

Timelapse Acquisition:

- Place sample on confocal or widefield fluorescence microscope

- Record timelapse movie during continuous illumination

- Use standard filter sets compatible with fluorophore excitation

- Continue acquisition until significant photobleaching occurs

Pre-processing:

- Perform background subtraction

- Apply drift compensation algorithms to correct for sample movement

Unmixing Algorithm Application:

- For samples with isolated fluorophores: Use Non-Negative Least Squares (NNLS) with manually identified bleaching fingerprints

- For complex cellular samples: Apply Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) or Non-increasing NMF (NI-NMF) to simultaneously estimate bleaching characteristics and abundances

- Use principal components of photobleaching curves as initial estimates

Validation:

- Compare results with known spectral properties of fluorophores

- Verify biological plausibility of unmixed distributions

Technical Notes: BAMM is particularly effective for organic dyes, autofluorescent biomolecules, and fluorescent proteins with distinct photobleaching rates [6]. The technique can be combined with spectral unmixing for enhanced multiplexing capability [6].

Reference Standards & Analysis Tools

QUEL-QAL Library: An open-source Python library designed to streamline quantitative analysis of fluorescence images using solid reference targets [7] [8]. This tool provides modular, reproducible workflows for key metrics including response linearity, limit of detection, depth sensitivity, and spatial resolution in alignment with AAPM TG311 and FDA guidelines [7].

Fluorescence SpectraViewer: Interactive online tools for plotting and comparing fluorescence excitation and emission spectra for over 250 fluorophores, essential for experimental planning and fluorophore selection [2].

Reference Standards: Fluorescent microsphere standards for microscopy and flow cytometry, plus ready-made fluorescent standard solutions for spectrofluorometry, enabling calibration of measurements across different instruments and timepoints [2].

Antifade Reagents for Photobleaching Mitigation

Table 4: Properties of Common Antifade Reagents [3]

| Reagent | Application Effectiveness | Stability & Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| p-phenylenediamine | Most effective for FITC; also works for Rhodamine | Light-sensitive (blackens with exposure); extremely dangerous skin contact |

| DABCO | Highly effective for FITC; slightly lower efficacy than p-phenylenediamine | More light-stable; higher safety profile |

| n-propylgallate | Most effective for Rhodamine; also effective for FITC | Prepare as 1% solution in glycerol/PBS |

| 2-mercapto-ethylamine | Used for chromosome/DNA specimens stained with propidium iodide, acridine orange, or Chromomycin A3 | Prepare as 0.1mM solution in Tris-EDTA buffer |

Application in Drug Development & Research

Advanced fluorescence techniques have revolutionized drug visualization in living systems. At the subcellular level, super-resolution microscopy enables exploration of the molecular landscape within individual cells and cellular responses to drugs [1]. When integrated with optical near-infrared II imaging, researchers can study complex spatiotemporal interactions between drugs and their surroundings across multiple biological scales [1].

The combination of these visualization approaches provides supplementary information on physiological parameters, metabolic activity, and tissue composition, leading to a comprehensive understanding of drug behavior [1]. For pharmaceutical researchers, these techniques enable tracking of drug distribution, target engagement, and therapeutic effects from subcellular to organismal levels, potentially redefining our understanding of pharmacology through analysis of drug micro-dynamics in subcellular environments [1].

Multiplexed fluorescence imaging particularly benefits immuno-oncology research, where studying immune cell locations relative to key biomarkers is essential, and neuroscience applications, where understanding neuronal synapse complexity requires simultaneous visualization of multiple proteins [5]. By enabling parallel observation of related components and processes, multiplexed fluorescence adds crucial context to observations, providing more meaningful results and revealing interdependencies that might otherwise be missed [5].

Fluorescence imaging has moved far beyond the simple visualization of protein localization. The field is now defined by the sophisticated engineering of both synthetic dyes and genetically encoded reporters, a synergy that enables the simultaneous monitoring of multiple biological processes in live cells—a capability central to advanced multiplexed imaging research [9].

This expansion addresses a fundamental challenge in systems biology: biological processes are not isolated but are the result of coordinated networks of signaling proteins, second messengers, and metabolites. While individual biosensors have provided profound insights, they cannot capture the complex, dynamic interactions between different molecular players [9]. The drive to overcome the spectral limitations of conventional microscopy has fueled innovations that separate signals not just by color, but also by time, space, and sophisticated computational unmixing. This document details the key reagents, quantitative data, and experimental protocols that form the modern toolkit for multiplexed fluorescence imaging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential materials used in the development and application of advanced fluorescent probes.

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| HaloTag/SNAP-tag [9] | Self-labeling protein tags that covalently bind to synthetic fluorophores, enabling the use of bright, photostable organic dyes with genetically targeted specificity. |

| EMcapsulins [10] | Genetically encoded nanocompartments that accumulate heavy metals for correlative electron microscopy, providing multiplexable genetic labels for ultrastructural analysis. |

| Time-Resolved FPs (tr-FPs) [11] | A family of fluorescent proteins engineered to exhibit distinct fluorescence lifetimes, enabling multiplexing in a single spectral channel via Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM). |

| Chemigenetic Biosensors [12] [9] | Hybrid biosensors combining a genetically encoded protein scaffold (sensing unit) with a synthetic fluorophore (reporting unit), offering enhanced optical properties and design flexibility. |

| SEPARATE Computational Unmixing [13] | A machine learning method that unmixes signals from two proteins labeled with the same fluorophore based on their distinct 3D spatial expression patterns, effectively doubling multiplexing capacity. |

| NIR-II Protein-Seeking Dyes [14] | Synthetic dyes that covalently bind to endogenous proteins like albumin, creating biomimetic NIR-II fluorescent complexes for high-contrast, deep-tissue imaging. |

Quantitative Comparison of Fluorescent Reporters

The selection of an appropriate reporter requires careful consideration of its photophysical properties. The tables below summarize key performance metrics for synthetic dyes and genetically encoded reporters.

Table 1: Properties of Advanced Synthetic Dyes and Chemigenetic Systems

| Dye/System Class | Excitation/Emission (nm) | Key Properties | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BODIPY Dyes [15] | 500-700 (tunable) | High quantum yield (>0.8), strong extinction coefficients, exceptional photostability. | Targeted cellular imaging (e.g., folate-conjugated for cancer imaging). |

| NIR-II Dye (CO-1080) [14] | 1044/1079 | Requires protein binding for brightness. | Deep-tissue bioimaging, lymphography, angiography. |

| HSA@CO-1080 FPs [14] | 1044/1079 | 22-fold fluorescence enhancement upon binding HSA; improved photostability & biocompatibility. | Multicolor deep-tissue imaging with 1064 nm excitation. |

Table 2: Properties of Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Reporters

| Reporter Class | Example | Key Properties | Readout Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-FP Biosensors [12] [9] | GCaMP8 (Ca2+), KTRs (Kinase Activity) | Excitation-ratiometric; large dynamic range; improved kinetics (GCaMP8: ms transients). | Change in fluorescence intensity or subcellular localization. |

| FRET-Based Biosensors [12] [9] [16] | AKAR (PKA Activity), RasAR (Ras Activity) | Sensitive to conformational changes; measures molecular interactions <10 nm. | Change in FRET efficiency between donor and acceptor FPs. |

| Time-Resolved FPs (tr-FPs) [11] | tr-mNeonGreen, tr-mScarlet | Fluorescence lifetime (1-5 ns) as a distinguishable parameter. | FLIM for multiplexing beyond spectral limits. |

| EMcapsulins [10] | 1M-QtFLAG, 2M-MxFLAG | 6 distinct classes; readable by TEM/SEM; automatic semantic segmentation possible. | Genetically encoded EM contrast for correlative microscopy. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiplexed Live-Cell Imaging with tr-FPs and FLIM

This protocol enables simultaneous imaging of up to nine cellular targets by leveraging the distinct fluorescence lifetimes of tr-FPs [11].

- Construct Preparation: Clone genes of interest (GOIs) as fusion proteins with selected tr-FPs (e.g., tr-mNeonGreen, tr-mScarlet) using standard molecular biology techniques. Ensure tr-FPs within the same spectral channel have well-separated lifetimes.

- Cell Preparation and Transfection:

- Culture mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T, HeLa) in appropriate media.

- Transfect with tr-FP fusion constructs using a preferred method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation). For multiple constructs, optimize DNA ratios to achieve balanced expression.

- Seed transfected cells onto glass-bottom imaging dishes and culture for 24-48 hours before imaging.

- FLIM Data Acquisition:

- Use a confocal or multiphoton microscope equipped with a FLIM module (time-correlated single photon counting, TCSPC, is recommended).

- Set excitation lasers to the appropriate wavelengths for the tr-FPs used.

- Acquire images at a resolution sufficient for the biological question. Collect a sufficient number of photons per pixel (typically >1000) for robust lifetime fitting.

- Data Analysis and Unmixing:

- Fit the fluorescence decay curve at each pixel to a multi-exponential model using the microscope's FLIM software or open-source tools.

- Assign a false color to each lifetime value corresponding to different tr-FPs.

- Generate a composite lifetime map where each color represents a different target protein, enabling visualization of multiple structures or activities within a single cell.

Protocol 2: Creating Biomimetic NIR-II Fluorescent Proteins

This protocol describes the creation of bright, biocompatible NIR-II fluorescent proteins through the covalent binding of synthetic dyes to a protein shell like Human Serum Albumin (HSA) [14].

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a solution of HSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, at a concentration of 10 µM.

- Add the protein-seeking NIR-II dye (e.g., CO-1080) from a concentrated DMSO stock to the HSA solution at a 1:1 molar ratio (10 µM final concentration). Ensure the final DMSO concentration is <1% to avoid protein denaturation.

- Incubation and Conjugation:

- Incubate the reaction mixture at 60 °C for 2 hours in the dark with gentle agitation. This temperature and time have been optimized for maximum yield.

- Purification:

- Allow the solution to cool to room temperature.

- Use ultrafiltration centrifugal devices (e.g., 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off) to separate the HSA@Dye conjugate from unreacted free dye. Centrifuge according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Wash the retentate with PBS three times to ensure complete removal of free dye.

- Characterization and Storage:

- Measure the absorption and fluorescence spectra of the purified HSA@Dye to confirm successful formation.

- The conjugate can be stored in PBS at 4 °C for short-term use or at -20 °C for long-term storage.

Protocol 3: Volumetric Multiplexed Imaging with SEPARATE

This protocol reduces the number of staining cycles required for 3D multiplexed imaging by pairing proteins and unmixing their signals computationally [13].

- Feature Extraction and Pairing:

- Acquire high-resolution 3D immunofluorescence images of each protein of interest individually stained in control tissue samples.

- Process these images through the feature extraction network (a convolutional neural network trained with contrastive learning) to generate feature-based distances between all proteins.

- Identify the optimal protein pairs by maximizing the minimum feature-based distance between paired proteins.

- Sample Staining and Imaging:

- For each pair of proteins (α and β), stain the experimental tissue sample with three fluorophore-conjugated antibodies:

- Fluorophore A: Anti-protein α

- Fluorophore B: Anti-protein β

- Fluorophore C: A cocktail of anti-protein α and anti-protein β

- Perform a single round of volumetric imaging (e.g., using a confocal microscope) to capture three channels: the signal of protein α, protein β, and the mixed signal.

- For each pair of proteins (α and β), stain the experimental tissue sample with three fluorophore-conjugated antibodies:

- Training Data Generation and Network Training:

- Generate a synthetic training dataset by linearly combining the single-protein images (α and β) with random ratios to simulate the mixed signal under various experimental conditions.

- Train the protein separation network using the synthetic mixed images as input and the corresponding single-protein images as targets.

- Signal Unmixing:

- Input the experimentally acquired mixed channel image into the trained protein separation network.

- The network will output two unmixed images, each containing the predicted signal for one of the paired proteins.

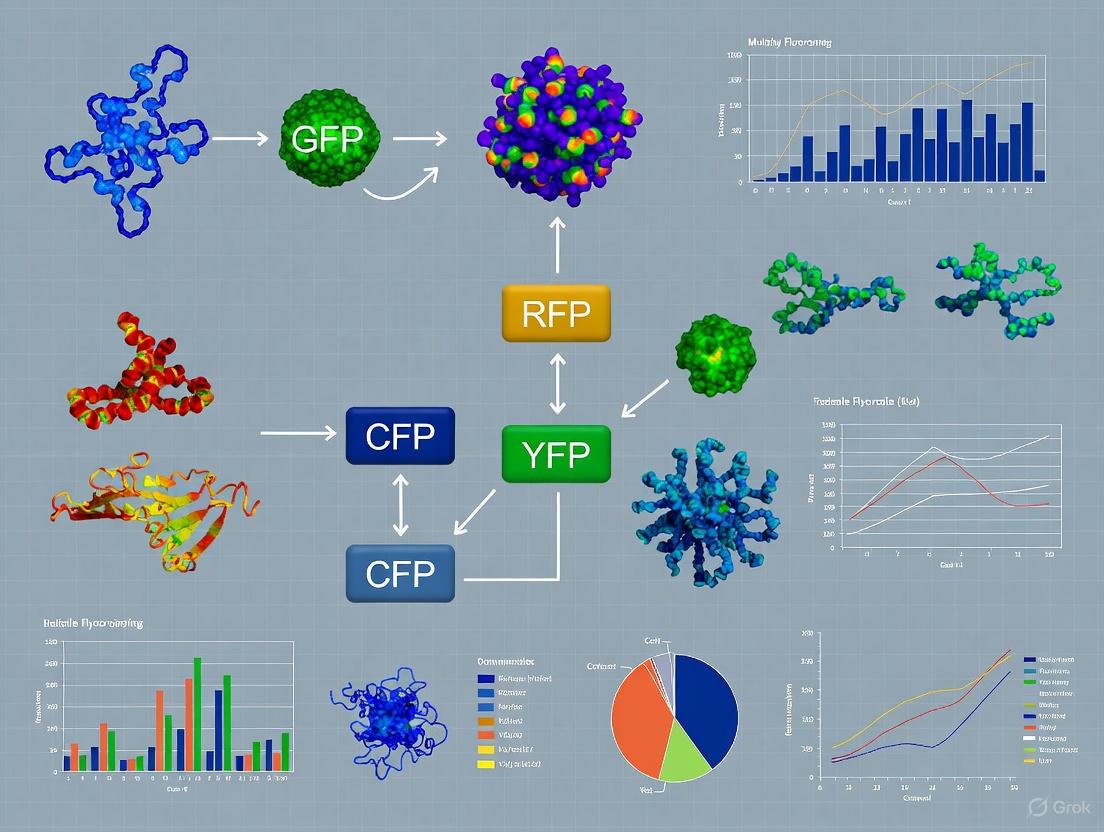

Visualizing Multiplexed Imaging Strategies

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and workflows behind advanced multiplexing techniques.

Multiplexing strategies move beyond color to use time and spatial patterns for separating signals.

Biosensor designs and hybrid probes combine genetic targeting with synthetic chemistry for enhanced performance.

The development of time-resolved fluorescent proteins (tr-FPs) represents a transformative advancement in fluorescence microscopy. A recent landmark study introduces a family of tr-FPs with rationally controlled fluorescence lifetimes, enabling unprecedented capabilities in live-cell imaging and quantitative biology [17]. This technology addresses a critical limitation in conventional fluorescence microscopy, which primarily relies on steady-state intensity signals, by unlocking the underexplored dimension of fluorescence lifetime [17].

For researchers engaged in multiplexed imaging and drug development, tr-FPs provide a solution to the spectral overlap problem that constrains conventional fluorescence techniques. By engineering proteins with distinct lifetimes despite spectral similarity, this approach enables simultaneous monitoring of multiple cellular components and processes, thereby facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of system complexity with quantitative accuracy [17].

Key Properties of Time-Resolved Fluorescent Proteins

Spectral and Lifetime Characteristics

The engineered tr-FPs cover the visible spectrum while exhibiting a wide range of fluorescence lifetimes. This orthogonal control over spectral and temporal properties is crucial for expanding multiplexing capability. Researchers can now design experiments combining multiple tr-FPs based on both color and lifetime separation, dramatically increasing the number of simultaneously imageable targets.

Quantitative Properties of tr-FPs:

| Protein Type | Excitation Maximum (nm) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Fluorescence Lifetime Range | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Fluorescent Proteins | ~380 [18] | 440-470 [18] | Not specified in results | FRET pairs, multicolor labeling [18] |

| Cyan Fluorescent Proteins | ~436 [18] | 470-500 [18] | Not specified in results | FRET biosensors with YFP [18] |

| Engineered tr-FPs | Visible spectrum coverage [17] | Visible spectrum coverage [17] | Wide range, rationally controlled [17] | Temporal-spectral resolved microscopy, multiplexed super-resolution [17] |

Performance Metrics for Biological Imaging

The development of tr-FPs focuses on optimizing key performance parameters essential for biological applications. These include:

- Brightness and Photostability: Critical for time-lapse imaging and long-term observation of cellular dynamics.

- Maturation Efficiency: Ensures rapid and complete fluorophore formation for accurate temporal analysis.

- Monomeric Character: Essential for fusion protein construction without perturbing native protein localization or function.

Experimental Applications and Workflows

Temporal-Spectral Resolved Microscopy

The tr-FP technology enables simultaneous imaging of nine different proteins in live cells, allowing researchers to correlate multiple cellular activities with cell cycle progression [17]. This application is particularly valuable for drug development professionals studying complex signaling networks and pathway interactions.

Experimental Protocol: Multiplexed Live-Cell Imaging with tr-FPs

Cell Line Preparation:

- Select appropriate cell line (e.g., HEK293, HeLa, or primary cells).

- Engineer cell lines to express tr-FP fusion proteins for targets of interest using lentiviral transduction or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in.

Microscope Setup Configuration:

- Utilize a fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) system equipped with:

- Pulsed laser source matching tr-FP excitation spectra

- Time-gated or frequency-domain detection capability

- Environmental chamber for live-cell maintenance (37°C, 5% CO₂)

- Configure appropriate filter sets for spectral separation of tr-FP signals.

- Utilize a fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) system equipped with:

Image Acquisition Parameters:

- Set temporal resolution based on biological process under investigation (seconds to minutes between frames).

- Adjust laser power to balance signal-to-noise ratio with phototoxicity concerns.

- Collect sufficient photons per pixel for accurate lifetime calculation (typically 1,000-10,000 photons).

Data Processing Workflow:

- Perform biexponential or multiexponential fitting of fluorescence decay curves.

- Apply lifetime unmixing algorithms to distinguish proteins with spectral overlap but distinct lifetimes.

- Generate spatial maps of protein localization and abundance.

Multiplexed Super-Resolution Microscopy

tr-FPs enable concurrent visualization of four proteins using lifetime signals in super-resolution microscopy [17]. This application pushes beyond the diffraction limit while maintaining multiplexing capability, essential for detailed structural studies in neurobiology and cell biology.

Protein Stoichiometry Quantification

The lifetime properties of tr-FPs enable quantification of cellular protein stoichiometry [17], providing crucial information about complex formation and protein-protein interactions that is inaccessible with conventional intensity-based measurements.

Advanced Implementation: SEPARATE Methodology

The SEPARATE (Spatial Expression PAttern-guided paiRing And unmixing of proTEins) methodology provides a complementary approach to multiplexed imaging that can be integrated with tr-FP technology [13]. This computational strategy enables volumetric multiplexed imaging by pairing proteins with distinct spatial expression patterns and unmixing their signals via machine learning.

Protein Pairing Strategy Based on Spatial Patterns

SEPARATE employs a feature extraction network trained through contrastive learning to quantify visual distinctiveness between protein spatial patterns [13]. The network calculates feature-based distances between protein clusters to identify optimal pairing for multiplexed imaging.

Quantitative Framework for Protein Pairing:

| Metric | Mathematical Definition | Functional Role | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interclass Distance (d_inter) | (d_{inter} = \frac{1}{ | {\bf P} | ( | {\bf P} | -1)}\sum_{p1 \ne p2} | \,{\bar{f}}_{p1}-{\bar{f}}_{p2} | ) [13] | Measures average distance between feature vectors of different proteins | ||

| Intraclass Distance (d_intra) | (d_{intra} = \frac{1}{ | {\bf P} | }\sum_{p}\frac{1}{Np}\sum_{i=1}^{Np} | \,{\bar{f}}_p-{f}_p^{(i)} | ) [13] | Measures average distance between feature vectors within the same protein | ||||

| Optimal Grouping (G_opt) | ({G}_{opt} = \mathop{\rm{argmax}}\limitsG\min ({d}{1},{d}{2},\ldots,{d}{n})) [13] | Identifies protein pairing that maximizes the minimum distance between paired proteins |

Integration of SEPARATE with tr-FP Technology

The combination of SEPARATE's computational unmixing capability with the intrinsic lifetime discrimination of tr-FPs creates a powerful multimodal platform for high-dimensional biological imaging.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for tr-FP Experiments:

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| tr-FP Plasmid Library | Coverage across visible spectrum with varied lifetimes [17] | Genetic encoding of time-resolved fluorescent markers |

| Cell Line Engineering Tools | Lentiviral vectors, CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in systems | Stable tr-FP fusion protein expression in cellular models |

| FLIM-Compatible Microscope | Pulsed laser source, time-gated detector, environmental control [17] | Acquisition of fluorescence lifetime data in live cells |

| Lifetime Analysis Software | Biexponential fitting, phasor analysis, lifetime unmixing algorithms | Extraction of lifetime information and signal separation |

| Mounting Media (fixed samples) | Prolong Diamond, Fluoromount-G, or custom formulations | Preservation of fluorescence and lifetime properties |

Protocol: Implementing tr-FPs for Live-Cell Multiplexing

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

Molecular Construct Design:

- Clone tr-FP genes in-frame with target proteins using Gibson assembly or traditional restriction enzyme methods.

- Select linkers of appropriate length (typically 5-15 amino acids) to minimize steric interference.

- Verify construct sequence integrity through Sanger sequencing before proceeding.

Cell Line Development:

- Transfect mammalian cells using polyethylenimine (PEI) or electroporation for initial validation.

- Select stable clones using appropriate antibiotics (e.g., puromycin, G418) over 2-3 weeks.

- Sort cells for uniform expression levels using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

FLIM Data Acquisition:

- Seed tr-FP expressing cells in glass-bottom dishes 24-48 hours before imaging.

- Switch to phenol-red free medium supplemented with HEPES buffer immediately before imaging.

- Acquire reference lifetime measurements from cells expressing individual tr-FP fusions.

- Perform multiplexed time-lapse imaging with temporal resolution appropriate for biological process.

Lifetime Unmixing and Validation:

- Fit fluorescence decay curves using maximum likelihood estimation.

- Apply linear unmixing algorithms to distinguish signals from proteins with overlapping spectra.

- Validate unmixing accuracy through control experiments with known expression ratios.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Increase laser power or acquisition time; optimize tr-FP expression level.

- Incomplete Lifetime Separation: Select tr-FPs with more distinct lifetimes; check for environmental factors affecting lifetime.

- Cellular Toxicity: Reduce laser power; use more photostable tr-FP variants; shorten acquisition periods.

- Incorrect Protein Localization: Verify fusion does not disrupt target protein function; test multiple linker designs.

The integration of time-resolved fluorescent proteins with advanced computational methods like SEPARATE provides researchers with an unprecedentedly powerful toolkit for investigating complex biological systems. These technologies enable quantitative analysis of multiple cellular components simultaneously, opening new avenues for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutics.

Fluorescence imaging is an indispensable tool in biomedical research, enabling the visualization of biological processes, disease progression, and therapeutic effects. However, conventional fluorescence imaging in the visible (400-700 nm) and first near-infrared window (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) faces significant challenges that limit its effectiveness for deep-tissue and prolonged imaging studies. These limitations include strong light scattering, significant tissue autofluorescence, and limited penetration depth, typically constraining high-fidelity imaging to superficial tissues [19] [20].

The emergence of second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm) fluorescence imaging represents a paradigm shift in optical bioimaging. By utilizing light in the 1000-1700 nm range, NIR-II imaging capitalizes on reduced photon scattering, minimal tissue autofluorescence, and lower light absorption by biological components [19]. This translates to superior imaging performance with deeper tissue penetration (up to several centimeters), enhanced spatial resolution, and significantly improved signal-to-background ratios compared to conventional imaging modalities [21] [20]. These advantages are particularly valuable in the context of multiplexed imaging, where simultaneously tracking multiple biomarkers is essential for understanding complex biological systems and disease mechanisms.

The NIR-II Advantage: Quantitative Performance Metrics

The theoretical advantages of NIR-II imaging are demonstrated by quantifiable improvements in key performance metrics compared to NIR-I imaging. The following table summarizes these advantages based on experimental data from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between NIR-I and NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging

| Performance Metric | NIR-I Imaging (700-900 nm) | NIR-II Imaging (1000-1700 nm) | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Penetration Depth | 1-6 mm [20] | Up to 20 mm [20] | ~3-5x deeper |

| Spatial Resolution | Micrometer-level [19] | Micrometer-level [19] | 2-3x higher clarity |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) | Moderate [19] | High [19] [20] | Significantly enhanced |

| Tissue Autofluorescence | Significant [19] | Greatly reduced [19] [20] | Drastically reduced |

The exceptional performance of NIR-II imaging stems from fundamental physical principles. Light scattering in biological tissues decreases monotonically as wavelength increases from 400 to 1700 nm. Furthermore, the optimal imaging window within the NIR-II spectrum is between 1000-1350 nm, where reduced scattering coincides with relatively low water absorption, maximizing photon penetration and signal fidelity [19].

Engineering Advanced NIR-II Fluorophores: Design Strategies and Properties

The development of high-performance NIR-II fluorophores has focused on several key structural families, each with distinct photophysical characteristics and design principles suitable for multiplexed imaging applications.

Organic Small-Molecule Fluorophores

Organic small-molecule dyes are particularly promising for clinical translation due to their superior biocompatibility, tunable optical properties, and potential for rapid body clearance [19] [22]. Major design strategies include:

- Donor-Acceptor-Donor (D-A-D) Architectures: These fluorophores feature an electron-accepting core (e.g., benzobisthiadiazole) symmetrically connected to electron-donating units via π-conjugated linkers. The HOMO-LUMO gap can be precisely tuned by modifying the electron-donating/withdrawing strengths of these components, allowing precise adjustment of absorption and emission profiles [19].

- Cyanine Derivatives: Characterized by a central polymethine chain conjugated to terminal heterocycles, cyanine fluorophores offer strong absorption and emission tunability [19].

- BODIPY and Aza-BODIPY Derivatives: These fluorophores provide excellent photostability and modular structures for chemical modification. Recent work has produced NIR-II emissive lipophilic membrane probes based on Aza-BODIPY that enable wash-free labeling with large ON/OFF ratios (>115) and fast staining rates (within 2 minutes) [23].

Innovative Design Strategies for Enhanced Performance

- Coulomb Attraction Interaction Tuning: A groundbreaking strategy for achieving NIR-II emission involves reducing Coulomb attraction interactions in excited states rather than simply reducing the fundamental band gap. This approach enables the development of fluorophores with low molecular weight (<500 Da) while maintaining emission beyond 1000 nm, facilitating better blood-brain barrier penetration and more efficient clearance [24].

- Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE): AIE-active fluorophores overcome aggregation-caused quenching by restricting intramolecular motion in the aggregated state, resulting in enhanced fluorescence quantum yields in nanoparticles or solid forms [19].

Table 2: Representative NIR-II Small-Molecule Fluorophores and Their Properties

| Fluorophore | Class | Emission Maximum (nm) | Molecular Weight (Da) | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH-1055 | D-A-D | 1055 | >500 | Early NIR-II dye, moderate QY | [25] |

| LS7 | GFP-chromophore derivative | >1000 | <449 | Low MW, targets Aβ fibrils, 22.7x fluorescence increase | [24] |

| BMP1 | Aza-BODIPY | NIR-II | N/A | Wash-free, fast membrane staining, large ON/OFF ratio | [23] |

| IR-FTEP | Cyanine derivative | 1100 | N/A | QY of 1.0% in water | [25] |

| Q4 | Cyanine derivative | 1100 | N/A | Good brightness for bioimaging | [25] |

Experimental Protocols for NIR-II Imaging Applications

Protocol: Labeling Lipid-Bilayer Structured Nanovectors with NIR-II Membrane Probes

This protocol describes the use of wash-free NIR-II membrane probes (e.g., BMP1) for labeling hybrid vesicles, adapted from methods reported for targeting colon cancer [23].

Materials:

- NIR-II membrane probe (BMP1 or BMP2)

- Hybrid vesicles (e.g., composed of probiotic outer membrane vesicles and anti-PD-L1 scFv-expressing cellular vesicles)

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS or HEPES)

- NIR-II fluorescence imaging system

Procedure:

- Probe Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of the NIR-II membrane probe (BMP1) in DMSO at a concentration of 1 mM.

- Vesicle Incubation: Add the BMP1 probe directly to the hybrid vesicle suspension at a final concentration of 1-5 µM.

- Staining Reaction: Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 2 minutes. The probe rapidly intercalates into the lipid bilayer without requiring washing steps.

- Purification (Optional): If necessary, remove unincorporated probe via gel filtration or dialysis.

- Validation: Characterize labeled vesicles using NIR-II fluorescence imaging to confirm incorporation efficiency and functionality.

Technical Notes:

- The wash-free property of BMP1 significantly streamlines the labeling process compared to traditional membrane probes that require extensive washing.

- This rapid staining protocol (2 minutes) preserves vesicle integrity and functionality.

- The large ON/OFF ratio (>115) provides high signal-to-background for sensitive detection.

Protocol: NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging of Brain Tissue in Alzheimer's Disease Models

This protocol utilizes low-molecular-weight NIR-II dyes for real-time imaging of amyloid-β deposits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease [24].

Materials:

- LS7 dye (GFP-chromophore based NIR-II fluorophore)

- Alzheimer's disease mouse model (e.g., APP/PS1 transgenic mice)

- Control wild-type mice

- NIR-II fluorescence imaging system with InGaAs camera

- Anesthesia equipment and reagents

Procedure:

- Dye Preparation: Prepare LS7 dye solution in physiological saline at a concentration of 100-500 µM.

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize mice using isoflurane or ketamine/xylazine cocktail according to approved animal protocols.

- Dye Administration: Administer LS7 dye via intravenous injection (e.g., tail vein) at a dose of 2-5 mg/kg.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire NIR-II fluorescence images at various time points post-injection (e.g., 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes) using appropriate NIR-II filters (1000-1400 nm range).

- Data Analysis: Quantify fluorescence signals in specific brain regions and compare between Alzheimer's model and control animals.

Technical Notes:

- The low molecular weight of LS7 (449 Da) facilitates efficient blood-brain barrier penetration.

- LS7 shows a 22.7-fold fluorescence increase upon binding to Aβ42 fibrils in vitro, providing high specificity.

- Real-time imaging enables dynamic monitoring of amyloid deposition progression.

NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging Workflow

Advanced Applications in Multiplexed Imaging and Therapeutics

Multiplexed Imaging with Computational Unmixing

Conventional multiplexed imaging is limited by the number of spectrally distinct fluorophores that can be simultaneously detected. The SEPARATE (Spatial Expression PAttern-guided paiRing And unmixing of proTEins) method overcomes this limitation by pairing proteins with distinct spatial expression patterns, labeling them with the same fluorophore, and computationally unmixing their signals based on three-dimensional spatial expression patterns using neural networks [13].

This approach effectively doubles multiplexing capability by imaging two proteins using a single fluorophore channel, significantly reducing the number of staining cycles required for visualizing multiple targets. The method employs a feature extraction network to quantify spatial distinction between proteins, followed by a protein separation network that unmixes signals from protein pairs labeled with identical fluorophores [13].

NIR-II Phototheranostics: Integrating Diagnosis and Therapy

NIR-II fluorophores have enabled the development of "phototheranostics" that combine diagnostic imaging with therapeutic interventions:

- Photothermal Therapy (PTT): NIR-II dyes with high photothermal conversion efficiency (e.g., 41-50%) can generate localized heat under laser irradiation, enabling precise tumor ablation while monitoring treatment efficacy in real-time [23] [22].

- Targeted Immunotherapy: Hybrid vesicles labeled with NIR-II membrane probes can execute targeted photothermal-immunotherapy, combining spatiotemporally controlled PTT with immunogenic vesicles to induce tandem-amplified immune responses and reprogram the tumor microenvironment [23].

- Image-Guided Surgery: The superior penetration and resolution of NIR-II imaging enables real-time visualization of tumor margins, lymphatic mapping, and precise surgical resection guidance, particularly for deep-seated tumors [21].

NIR-II Phototheranostics Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging Applications

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Membrane Probes | Labeling lipid-bilayer nanovectors | BMP1, BMP2 [23] | Wash-free, fast staining (2 min), large ON/OFF ratio (>115) |

| Low-MW Brain-Penetrant Dyes | Blood-brain barrier crossing, brain imaging | LS series dyes [24] | MW <500 Da, emission >1000 nm, target-specific (e.g., Aβ) |

| Donor-Acceptor-Donor Dyes | High-performance NIR-II imaging | CH-1055, IR-FTEP [25] [19] | Tunable emission, high brightness, good photostability |

| Hybrid Vesicle Systems | Targeted drug delivery and immunotherapy | OMV + aPD-L1 scFv vesicles [23] | Immunogenic, actively tumor-targeting, combinable with PTT |

| Computational Unmixing Tools | Multiplexed imaging beyond spectral limits | SEPARATE method [13] | Neural network-based, doubles multiplexing capability |

The development of NIR-II fluorophores and photostable probes represents a significant advancement in fluorescence imaging, directly addressing the critical limitations of penetration depth and photobleaching that have constrained traditional approaches. These innovations are particularly valuable for multiplexed imaging studies, where tracking multiple biomarkers simultaneously provides comprehensive insights into complex biological systems.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on creating fluorophores with emission further into the NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm) region for even better performance, improving biocompatibility and clearance profiles to facilitate clinical translation, and integrating artificial intelligence for enhanced image analysis and unmixing capabilities [26]. As these technologies mature, they will undoubtedly expand our ability to visualize and understand biological processes at unprecedented depths and resolution, accelerating drug development and advancing our fundamental knowledge of disease mechanisms.

The integration of NIR-II imaging with targeted therapeutic interventions creates powerful theranostic platforms that promise to revolutionize both biomedical research and clinical practice. By providing real-time feedback on drug distribution, target engagement, and treatment efficacy, these approaches represent a significant step toward personalized medicine with enhanced precision and effectiveness.

Advanced Techniques and Translational Applications in Spatial Biology

Multiplexed fluorescence imaging represents a paradigm shift in spatial biology, enabling the simultaneous visualization of dozens to hundreds of biomolecules within their native tissue context. These methods provide unique insights into complex biological systems by preserving spatial information that is lost in dissociative analytical techniques. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the principles, applications, and practical implementation of these technologies is crucial for advancing biomarker discovery, drug target validation, and patient stratification strategies. This application note focuses on three prominent cyclic imaging methods—Cyclic Immunofluorescence (CycIF), Multiplexed Error-Robust Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (MERFISH), and the novel SPECTRE-Plex approach—detailing their fundamental principles, optimized protocols, and research applications.

The critical advantage of cyclic imaging methods over conventional fluorescence techniques lies in their ability to overcome the physical limitations of spectral overlap. While conventional immunofluorescence is typically limited to four to seven markers due to fluorophore emission spectra overlap, cyclic methods achieve high multiplexing through sequential imaging and signal removal or inactivation [27]. This capability makes them particularly valuable for characterizing complex cellular microenvironments, such as the tumor microenvironment, where intricate cell-cell interactions determine disease progression and treatment response [28].

Core Principles of Cyclic Imaging

Cyclic imaging methods share a common fundamental strategy: the sequential application, imaging, and removal of fluorescent signals to build high-dimensional datasets from a single sample. This iterative process bypasses the spectral limitations of traditional fluorescence microscopy, wherein the number of simultaneously detectable markers is constrained by the available fluorophore spectrum and filter sets. The cyclic approach typically involves four key phases that repeat for each imaging cycle: (1) staining with fluorescently-labeled probes, (2) multi-channel image acquisition, (3) signal inactivation or removal, and (4) image registration and alignment using a consistent reference marker, such as a nuclear stain [29].

The implementation details, however, vary significantly between protein-based detection (e.g., CycIF, SPECTRE-Plex) and RNA-based detection (e.g., MERFISH) methods, each with distinct advantages for different research applications. Protein-based methods provide direct information about protein expression and post-translational modifications that often correlate with cellular function, while RNA-based methods offer comprehensive transcriptomic profiling at single-cell resolution within intact tissues [27].

Comparative Analysis of Cyclic Imaging Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Key Cyclic Imaging Technologies

| Method | Target | Multiplexing Capacity | Resolution | Key Principle | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CycIF [29] | Proteins | Up to 60-plex | Subcellular | Sequential immunofluorescence with chemical dye inactivation | 14-36 hours (for ~7 cycles) |

| MERFISH [30] | RNA | Hundreds to thousands of genes | Single-molecule | Sequential FISH with error-robust barcoding | Several days |

| SPECTRE-Plex [31] | Proteins | Demonstrated 22-plex | Subcellular (high-NA objectives) | Optimized dye inactivation with microfluidics | ~8 hours (for 7 cycles) |

| CODEX [27] | Proteins | Up to 60-plex | Subcellular | DNA oligonucleotide barcoding with hybridization cycles | Varies |

Cyclic Immunofluorescence (CycIF)

Principles and Workflow

Cyclic Immunofluorescence (CycIF) is an accessible, highly multiplexed immunofluorescence imaging method that utilizes conventional microscopes and commercially available reagents. The method was specifically developed to overcome the limitations of conventional immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence, which are typically restricted to imaging a few markers simultaneously [29]. CycIF achieves multiplexing through sequential rounds of staining, imaging, and fluorophore inactivation, building a high-dimensional image dataset cycle by cycle.

The fundamental CycIF workflow consists of four key steps that repeat for each cycle: (1) immunostaining with directly conjugated antibodies targeting 3-4 protein antigens per cycle, (2) nuclear staining with Hoechst or DAPI for image registration, (3) multi-channel fluorescence imaging, and (4) chemical inactivation of fluorophores using a mild base with hydrogen peroxide under light exposure [29] [32]. This process preserves tissue integrity while progressively building a multiplexed dataset. A notable advantage of CycIF is that the signal-to-noise ratio often improves with successive cycles due to reduction of autofluorescence through repeated bleaching steps [29].

CycIF Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: The CycIF workflow involves iterative cycles of staining, imaging, and bleaching to build high-plex images from standard FFPE tissue sections.

Detailed CycIF Protocol

Sample Preparation

- Tissue Sections: Cut 5μm sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks using standard microtomy procedures [29].

- Deparaffinization: Incubate slides at 60°C for 15 minutes, followed by two incubations in 100% Histoclear (first for 5 minutes, then for 10 minutes) at room temperature [31].

- Rehydration: Perform sequential 5-minute incubations in decreasing ethanol concentrations (100%, 95%, 75%, 50%, and 0%) at room temperature [31].

- Antigen Retrieval: Incubate slides in antigen retrieval buffer (e.g., citrate-based buffer, pH 6.0), heat to 100°C for 20 minutes, then cool to room temperature for 20-40 minutes [31] [29].

- Blocking: Wash slides twice with PBS and incubate in blocking buffer (e.g., 3% BSA in PBS) for 1 hour to reduce non-specific antibody binding [31].

Pre-staining and Initial Bleaching

- Pre-staining: Incubate samples with secondary antibodies to reduce autofluorescence caused by non-specific antibody binding in subsequent cycles [33].

- Initial Bleaching: Treat samples with fluorophore oxidation solution (high pH hydrogen peroxide with light exposure) to inactivate fluorophores and reduce background autofluorescence [29].

Cyclic Staining and Imaging

- Primary Antibody Staining: For each cycle, incubate with 3-4 directly conjugated primary antibodies diluted in antibody dilution buffer for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Directly conjugated antibodies are preferred over indirect immunofluorescence to avoid species limitation issues [32].

- Nuclear Staining: Include Hoechst 33342 (1-2 μg/mL) or DAPI in each cycle to facilitate image registration across cycles [29].

- Image Acquisition: Acquire four-channel images using a conventional epifluorescence microscope or slide scanner. For large specimens, collect tiled images with consistent exposure settings across cycles.

- Fluorophore Inactivation: After imaging, incubate slides in bleaching solution (100mM Tris pH 8.0, 3% H₂O₂) under bright light for 1 hour to inactivate fluorophores [29].

- Cycle Repetition: Repeat the staining-imaging-bleaching cycle until all targets have been imaged. Typical CycIF experiments involve 5-15 cycles to generate 15-60-plex datasets [29].

Post-cycling Processing

- Optional H&E Staining: After the final CycIF cycle, stain with hematoxylin and eosin to enable correlation with conventional histopathology [33] [29].

- Image Processing: Register and stitch individual image panels across cycles using nuclear staining as a reference. Process images to generate a high-dimensional representation using tools like MCMICRO pipeline [33].

CycIF Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CycIF Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Antibodies | Alexa Fluor 488, 555, 647 conjugates [32] | Target protein detection | Prefer directly conjugated antibodies; Alexa Fluor dyes bleach efficiently |

| Nuclear Stains | Hoechst 33342, DAPI [29] | Nuclear segmentation & image registration | Include in every cycle for consistent registration |

| Bleaching Reagents | Hydrogen peroxide, Tris base [29] | Fluorophore inactivation | High pH H₂O₂ solution with light exposure |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Citrate buffer (pH 6.0), Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) [31] | Epitope exposure | Required for FFPE samples; optimal pH varies by antigen |

| Blocking Buffers | BSA (3-5%), serum, commercial blocking reagents [31] | Reduce non-specific binding | Critical for minimizing background in multiplexed imaging |

Multiplexed Error-Robust FISH (MERFISH)

Principles and Workflow

Multiplexed Error-Robust Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (MERFISH) is a single-molecule transcriptomic imaging method that enables the quantification and spatial mapping of hundreds to thousands of RNA species simultaneously in individual cells within intact tissues [30]. As an image-based approach to single-cell transcriptomics, MERFISH combines single-molecule FISH with combinatorial barcoding and sequential hybridization to overcome the spectral limitations of conventional fluorescence microscopy.

The core principle of MERFISH involves a two-step labeling process using encoding probes with readout sequences [30]. First, unlabeled DNA "encoding probes" are hybridized to cellular RNA. These probes contain a targeting region complementary to the RNA of interest and a barcode region comprising a series of custom binding sites ("readout sequences"). The specific combination of readout sequences determines the optical barcode for each RNA species. Second, fluorescently labeled "readout probes" complementary to these sequences are hybridized in successive rounds of imaging, with each round detecting one bit of the barcode. The combinatorial barcoding scheme incorporates error-correction mechanisms to ensure accurate RNA identification despite occasional imaging or hybridization errors [30].

MERFISH Workflow Visualization

Diagram 2: MERFISH utilizes encoding probes with combinatorial barcodes that are read out through successive hybridization and imaging cycles to profile hundreds to thousands of RNAs simultaneously.

Optimized MERFISH Protocol

Probe Design Considerations

- Target Region Length: Encoding probes with target regions of 30-50 nucleotides provide optimal binding efficiency and specificity. Systematic optimization has shown that signal brightness depends weakly on target region length within this range, with 40 nt providing a good balance of efficiency and specificity [30].

- Barcode Design: Implement error-robust barcoding schemes (e.g., Hamming distance-based codes) to minimize misidentification errors during decoding.

- Probe Set Size: Include approximately 30-100 encoding probes per target RNA to achieve high molecular detection efficiency through binding redundancy [30].

Sample Preparation and Hybridization

- Fixation: Fix cells or tissue sections with 4% paraformaldehyde for optimal RNA preservation and probe accessibility.

- Permeabilization: Treat samples with detergent solution (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100) or protease digestion to enable probe access to RNA targets.

- Encoding Probe Hybridization: Hybridize encoding probes to the sample using optimized buffer conditions. Recent protocol improvements demonstrate that hybridization duration can be significantly reduced through buffer optimization without sacrificing efficiency [30].

- Hybridization Buffer Optimization: Screen formamide concentrations (typically 10-30%) with fixed hybridization temperature (37°C) to identify optimal stringency conditions for specific probe sets [30].

Sequential Imaging and Stripping

- Readout Probe Hybridization: For each round of imaging, hybridize fluorescent readout probes complementary to specific readout sequences in the encoding probes.

- Multi-channel Imaging: Acquire images for all fields of view using appropriate filter sets. Include fiducial markers for image registration if imaging large areas.

- Probe Stripping: After each imaging round, remove readout probes using chemical denaturation (e.g., formamide-based stripping buffers) or enzymatic degradation.

- Cycle Repetition: Repeat the readout hybridization-imaging-stripping cycle until all bits of the barcode have been read. Typical MERFISH experiments involve 8-16 rounds of hybridization to encode hundreds to thousands of RNA species [30].

Image Processing and Data Analysis

- Image Registration: Align images from successive hybridization rounds using fiducial markers or nuclear stains.

- Barcode Decoding: Identify RNA molecules by decoding the fluorescence on-off pattern across imaging rounds for each detected spot.

- Error Correction: Utilize the built-in error-correction capability of the barcoding scheme to correct for missing or extra bits in the fluorescence patterns.

- Cell Segmentation: Identify cell boundaries using nuclear stains or membrane markers to assign transcripts to individual cells.

Recent MERFISH Protocol Optimizations

Recent systematic optimization of MERFISH protocols has identified several key improvements:

- Hybridization Acceleration: Modified hybridization conditions can substantially enhance the rate of probe assembly, reducing hybridization time while maintaining or improving signal brightness [30].

- Buffer Composition: New imaging buffer formulations improve photostability and effective brightness for commonly used MERFISH fluorophores, enhancing signal-to-noise ratio throughout extended imaging sessions [30].

- Reagent Stability: Implementation of stabilization approaches mitigates the "aging" of reagents during prolonged experiments, maintaining consistent performance across multiple hybridization rounds [30].

- Background Reduction: Prescreening readout probes against sample types identifies and mitigates tissue-specific non-specific binding, reducing false-positive counts [30].

SPECTRE-Plex: An Advanced Successive Staining Approach

Principles and Innovations

SPECTRE-Plex (Spatial Photo-inactivation Enhanced Cyclic Target REsolved multiPlexing) represents a recent advancement in cyclic imaging technology that addresses several limitations of existing methods, particularly in terms of speed, resolution, and practical implementation [31]. This end-to-end system integrates novel chemical, microfluidic, and optical innovations to enable rapid, high-resolution multiplex immunofluorescence imaging at relatively low cost compared to existing platforms.

The key innovations of SPECTRE-Plex include:

- Advanced Dye Inactivation Chemistry: Implementation of meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (m-CPBA) as a dye inactivation agent that operates orders of magnitude faster than previously used reagents (LiBH₄ or H₂O₂) and does not generate oxygen bubbles that can interfere with microfluidics [31].

- Refractive Index-Matched Microfluidics: Development of a PDMS-based microfluidic device ("invisi-slip") with an embedded fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) window that enables aberration-free imaging with high-NA water dipping objectives [31].

- Integrated Automation: Custom python and μ-manager software that coordinates imaging, positioning, and fluidics for efficient and rapid repetition of cycles [31].

- Kinetic Analysis Capability: The in-situ design allows simultaneous imaging and antibody labeling, enabling direct measurement of antibody binding kinetics on tissues under various conditions [31].

SPECTRE-Plex Workflow and Protocol

System Setup

- Microfluidic Chamber: Assemble the invis-slip system with FEP optical window to create a refractive index-matched imaging environment.

- Fluidics Integration: Connect temperature-controlled fluidics with bubble-free operation enabled by m-CPBA chemistry.

- Objective Selection: Utilize high-NA water dipping objectives (e.g., 16×/0.8 NA for large FOV or 60×/1.2 NA for subcellular resolution) [31].

Staining and Imaging Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Follow standard FFPE processing including deparaffinization, rehydration, antigen retrieval, and blocking as described in the CycIF protocol [31].

- Automated Cycling: Implement iterative cycles of staining, washing, imaging, and dye inactivation in situ using integrated fluidics and imaging control.

- Rapid Dye Inactivation: Apply m-CPBA solution for efficient fluorophore inactivation without bubble formation [31].

- High-Resolution Imaging: Capture tiled images using a highly repeatable motorized stage with automated image registration.

Binding Kinetics Applications

The SPECTRE-Plex system enables unique applications for directly measuring antibody binding kinetics on tissues:

- Temperature Optimization: Assess binding half-times at different temperatures (e.g., anti-Muc2 IgG t₁/₂ = 50 min at 22°C vs. 13 min at 37°C) [31].

- Condition Screening: Evaluate effects of solution pH, ionic strength, or other parameters on antibody binding efficiency.

- Therapeutic Antibody Validation: Characterize binding behavior of therapeutic antibodies or small molecules directly in tissue contexts [31].

Performance Advantages

SPECTRE-Plex demonstrates significant practical advantages over existing cyclic imaging methods:

- Speed: A 7-cycle run can be completed in approximately 8 hours compared to 14-36 hours for most manual or semi-automated cyclical methods [31].

- Resolution: Compatibility with high-NA water dipping objectives enables subcellular resolution imaging not typically achievable with conventional cyclic imaging systems limited by air objectives or refractive index mismatches [31].

- Scalability: The automated, integrated system supports consistent and reproducible data acquisition across multiple samples and experiments.

Applications in Biomedical Research

Tumor Microenvironment Characterization

Multiplexed cyclic imaging methods have proven particularly valuable in immuno-oncology research, where understanding the spatial organization of immune cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME) has become crucial for predicting treatment response and developing new therapeutic strategies [28]. These technologies enable comprehensive profiling of immune cell populations, including:

- Immune Contexture Assessment: Simultaneous identification of multiple immune cell subsets (T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells) and their functional states within tissue architecture [28].

- Spatial Relationship Mapping: Analysis of cell-cell interactions and neighborhood relationships that influence therapeutic response, such as the proximity of cytotoxic T cells to tumor cells expressing PD-L1 [28].

- Tumor Heterogeneity Characterization: Resolution of intratumoral heterogeneity through high-plex protein or RNA expression profiling across different tumor regions [29].

Drug Development Applications

For drug development professionals, cyclic imaging methods offer powerful tools for:

- Biomarker Discovery: Identification of novel predictive or prognostic biomarkers through comprehensive tissue profiling [28].

- Pharmacodynamic Assessment: Evaluation of drug effects on multiple signaling pathways and cell populations simultaneously within intact tissues.

- Therapeutic Antibody Validation: Direct measurement of antibody binding kinetics and target engagement in relevant tissue contexts using systems like SPECTRE-Plex [31].

- Mechanistic Studies: Elucidation of drug mechanisms of action through spatial analysis of pathway modulation and cellular responses.

Integration with Complementary Technologies

Cyclic imaging methods are increasingly integrated with other spatial analysis platforms to provide comprehensive tissue characterization:

- Spatial Transcriptomics Correlation: Combination of protein-based cyclic imaging (CycIF, SPECTRE-Plex) with RNA-based methods (MERFISH) applied to adjacent tissue sections to correlate protein and RNA expression patterns [27].

- Single-Cell Sequencing Integration: Registration of multiplexed imaging data with single-cell RNA sequencing data from the same or similar samples to validate and spatialize cell type identities [29].

- Clinical Histopathology Correlation: Registration of high-plex cyclic imaging data with standard H&E staining and clinical immunohistochemistry to bridge discovery research with diagnostic practice [33] [29].

Technical Considerations and Challenges

Experimental Design Considerations

Successful implementation of cyclic imaging methods requires careful experimental planning:

- Panel Design: Strategic selection of markers based on biological questions, with consideration of antibody performance, expression levels, and cellular localization.

- Cycle Ordering: Placement of high-signal antibodies in early cycles and lower-signal antibodies in later cycles, as background autofluorescence tends to decrease with successive bleaching steps [33].

- Validation: Rigorous validation of antibody specificity and performance under cyclic conditions, including assessment of epitope stability through multiple cycles.

- Controls: Inclusion of appropriate positive and negative controls to ensure data quality and reproducibility.

Data Analysis Challenges

The high-dimensional data generated by cyclic imaging methods presents significant computational challenges:

- Image Processing: Efficient registration and stitching of large image datasets across multiple cycles and channels [34].

- Cell Segmentation: Accurate identification of cellular boundaries, particularly in dense tissue regions, which can be complicated by artifacts such as uneven illumination, antibody aggregates, and tissue folding [34].

- Cell Type Classification: Integration of high-dimensional marker data to define cell types and states, requiring specialized computational approaches [34].

- Spatial Analysis: Quantitative assessment of spatial patterns, cell-cell interactions, and tissue organization using appropriate statistical methods.

Artifact Identification and Mitigation

Cyclic imaging data can be affected by various technical artifacts that require detection and correction:

- Fluorescent Contaminants: Autofluorescent particles or debris that can be misidentified as specific signals [34].

- Uneven Immunolabeling: Regional variations in staining intensity due to fluidics or incubation inconsistencies [34].

- Image Blur: Out-of-focus regions that reduce segmentation and quantification accuracy [34].

- Antibody Aggregates: Non-specific clusters of antibodies that generate false-positive signals [34].

Emerging computational tools, including machine learning approaches, are being developed to automatically identify and correct these artifacts to improve data quality and reliability [34].

Cyclic imaging methods—including CycIF, MERFISH, and the novel SPECTRE-Plex approach—represent powerful and increasingly accessible technologies for high-dimensional spatial analysis of biological tissues. Each method offers unique advantages: CycIF provides an accessible entry point for high-plex protein imaging using conventional microscopes; MERFISH enables comprehensive transcriptomic profiling at single-molecule resolution; and SPECTRE-Plex delivers accelerated, high-resolution multiplexed imaging through integrated automation and optimized chemistry.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these technologies offer unprecedented capabilities to characterize complex biological systems, discover novel biomarkers, and validate therapeutic mechanisms within the native tissue context. As these methods continue to evolve through improvements in reagents, instrumentation, and computational analysis, they are poised to become increasingly integral to both basic research and translational applications, ultimately contributing to more personalized and effective therapeutic strategies.

The spatial organization of cells within healthy and diseased tissues is a critical determinant of physiological function and pathological states. For decades, traditional immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence have been limited to visualizing only one or two protein markers in a single tissue section, restricting our understanding of complex cellular ecosystems [35]. The emergence of multiplexed fluorescence imaging technologies has revolutionized our ability to characterize tissues at the single-cell level while preserving precious spatial context. Among these advanced methods, CODEX (Co-Detection by indEXing) and SABER (Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction) represent two powerful approaches that leverage DNA barcoding to overcome the limitations of conventional microscopy [35] [36]. CODEX utilizes DNA-conjugated antibodies and cyclic hybridization to enable highly multiplexed protein detection, while SABER employs primer exchange reactions to create long DNA concatemers for signal amplification in nucleic acid detection. These complementary technologies are rapidly advancing biological discovery and therapeutic development by providing unprecedented views into cellular organization, cell-cell interactions, and tissue microenvironments in conditions ranging from cancer to autoimmune diseases [35] [36].

CODEX: Principles and Workflow