NIR-I vs NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging: A Comprehensive Analysis of Resolution and Contrast for Biomedical Applications

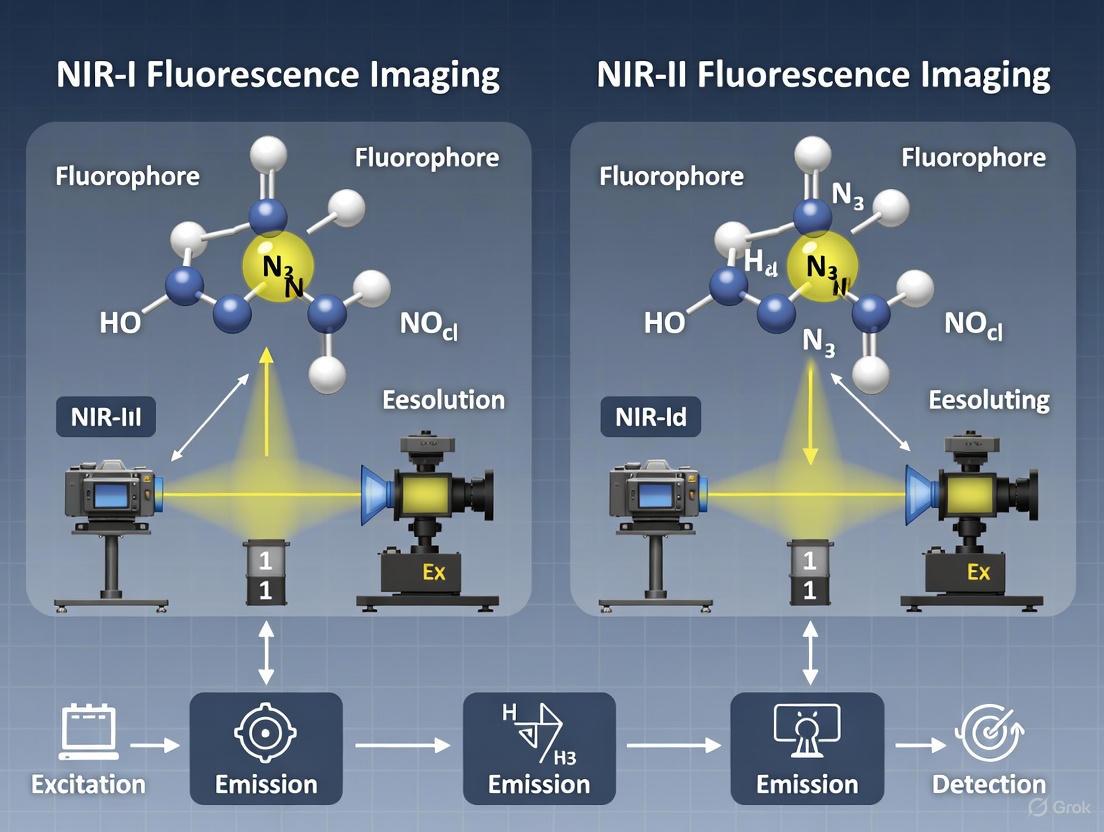

This article provides a detailed comparison of NIR-I (700–900 nm) and NIR-II (1000–1700 nm and beyond) fluorescence imaging, focusing on the fundamental mechanisms that confer superior resolution and contrast in...

NIR-I vs NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging: A Comprehensive Analysis of Resolution and Contrast for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of NIR-I (700–900 nm) and NIR-II (1000–1700 nm and beyond) fluorescence imaging, focusing on the fundamental mechanisms that confer superior resolution and contrast in the NIR-II window. We explore the foundational principles of light-tissue interactions, including reduced photon scattering, minimal autofluorescence, and the newly recognized beneficial role of water absorption. The review covers the latest methodological advances in NIR-II fluorophores and imaging instrumentation, alongside their growing applications in cancer imaging, vascular mapping, and image-guided surgery. We also address key challenges in probe development and image optimization, and present comparative validation data that underscores the clinical potential of NIR-II imaging for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking deeper tissue visualization.

The Physics of Light: Unraveling Why Wavelength Matters in Bioimaging

Fluorescence imaging has become a cornerstone technique in biomedical research, enabling the non-invasive visualization of biological processes in live subjects. However, the interaction of light with biological tissues—specifically through the processes of absorption and scattering—presents significant challenges. These phenomena can attenuate signal intensity, reduce image clarity, and limit penetration depth. To overcome these limitations, researchers have identified specific spectral regions where light maintains superior tissue-penetrating capabilities, known as "biological windows".

The progression from the visible spectrum to the near-infrared (NIR) region represents a paradigm shift in bioimaging. While conventional imaging operated in the visible (400-700 nm) and NIR-I (700-900 nm) windows, the discovery of the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 900-1880 nm) has unlocked unprecedented capabilities for deep-tissue, high-fidelity imaging [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these optical windows, focusing on their fundamental properties, performance metrics, and practical applications in biomedical research.

Defining the Spectral Windows

The optical landscape for bioimaging is divided into distinct regions based on how light interacts with biological components. The defining characteristics of each window are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Definition and Properties of Optical Biological Windows

| Spectral Window | Wavelength Range | Defining Characteristics | Key Interactions with Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible | 400 - 700 nm | High photon energy; strong tissue autofluorescence | Strong scattering and absorption by hemoglobin, melanin, and water |

| NIR-I | 700 - 900 nm | Reduced scattering vs. visible light; first "biological window" | Lower hemoglobin absorption; moderate water absorption |

| NIR-II | 900 - 1880 nm [2] [1] | Significantly reduced scattering and autofluorescence | Low absorption except at specific peaks (e.g., ~1200 nm, ~1450 nm, ~1930 nm) [1] |

| NIR-IIa | 1300 - 1400 nm [2] | Sub-window of NIR-II | Favorable balance of scattering and absorption |

| NIR-IIb | 1500 - 1700 nm [2] | Sub-window of NIR-II | Further reduced scattering |

| NIR-IIx | 1400 - 1500 nm [2] [1] | Region around water absorption peak at ~1450 nm | Moderate water absorption improves contrast [2] |

| NIR-IIc | 1700 - 1880 nm [1] | Sub-window of NIR-II | Similar properties to NIR-IIb |

| NIR-III | 2080 - 2340 nm [1] | Newly proposed window beyond NIR-II | High water absorption requires very bright probes |

The conventional NIR-II window is defined as 900-1880 nm, moving beyond the historical limit of 1700 nm [1]. This expansion is supported by a refined understanding of water absorption, which demonstrates that regions surrounding absorption peaks (like NIR-IIx, 1400-1500 nm) can be harnessed for high-contrast imaging rather than avoided [2].

Physical Principles and Performance Comparison

The Role of Scattering and Absorption

The quality of in vivo fluorescence imaging is predominantly governed by two physical phenomena: scattering and absorption.

- Scattering causes photons to deviate from their original path, blurring the image and reducing spatial resolution.

- Absorption attenuates the total number of photons, diminishing signal intensity.

In the NIR-II window, the reduced scattering of longer wavelengths is a key advantage. Scattering in biological tissues decreases monotonically with increasing wavelength from 400 to 1700 nm [3]. This reduction directly translates to improved image clarity and spatial resolution.

Contrary to traditional belief, recent research reveals that moderate absorption can be beneficial. While excessive absorption depletes signal, strategic use of absorption peaks preferentially attenuates multiple-scattered photons (which have longer path lengths) over ballistic signal photons. This phenomenon increases the proportion of useful signal photons reaching the detector, thereby enhancing the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) [2] [1].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The theoretical advantages of longer wavelength imaging are confirmed by experimental data quantifying performance across different windows.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Optical Windows for In Vivo Imaging

| Performance Metric | NIR-I (700-900 nm) | NIR-II (900-1880 nm) | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Lower resolution due to higher scattering | ~2.1x higher resolution than NIR-I [4] | Murine vascular imaging; distinction of adjacent capillaries |

| Penetration Depth | < 1 cm [3] | Up to several centimeters [3]; ~1.7x deeper than NIR-I [4] | Non-invasive through-scalp/skull brain imaging in mice [4] |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) | Moderate, limited by autofluorescence | ~3.5x higher than NIR-I [4] | Cerebral vasculature imaging with significantly improved contrast |

| Tissue Autofluorescence | Significant | Minimal [3] | Dramatically reduced background noise in NIR-II images |

Monte Carlo simulations of photon transport through biological tissues further validate these findings, demonstrating that the NIR-IIx (1400-1500 nm) and 1880-2080 nm windows provide superior SBR and structural similarity compared to other NIR-II sub-windows [2].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Monte Carlo Simulation for Window Evaluation

Purpose: To simulate photon propagation in biological tissues and evaluate imaging quality across different spectral windows.

Workflow Overview:

Protocol Details:

- Define Spectral Windows: Establish specific ranges for comparison (e.g., NIR-IIa: 1300-1400 nm, NIR-IIx: 1400-1500 nm, NIR-IIb: 1500-1700 nm, NIR-IIc: 1700-1880 nm) [2].

- Set Optical Parameters: Incorporate wavelength-dependent absorption coefficients (μa), particularly for water, and reduced scattering coefficients (μs') into the model [2] [1].

- Photon Propagation: Use Monte Carlo methods to simulate the random walk of numerous photons (typically millions) through simulated tissue [1].

- Path Length Analysis: Differentiate between ballistic (direct-path) photons and scattered photons, noting that absorbed photons are preferentially those with longer path lengths [2].

- Image Quality Quantification: Calculate key metrics including Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR), Structure Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of point spread functions [2].

In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging Protocol

Purpose: To experimentally validate imaging performance across different optical windows in live animal models.

Workflow Overview:

Protocol Details:

- Fluorophore Selection: Choose bright, biocompatible fluorophores with emission covering target windows:

- PbS/CdS Quantum Dots: Tunable emission from 1100 nm to >1700 nm; used for comparing NIR-II sub-windows [2] [1].

- Organic Dyes: CH1055-PEG (D-A-D scaffold); IR-12N3; ICG (FDA-approved, emits in NIR-II beyond 1000 nm) [5] [3].

- Targeted Probes: EPH-3-DBS (EphA2-targeted) for specific cancer imaging [6].

- Animal Preparation: Utilize established models (e.g., murine cerebral vasculature, tumor xenografts, orthotopic cancer models).

- Imaging System Configuration:

- Excitation Source: Tunable lasers or fixed-wavelength lasers matched to fluorophore absorption.

- Detection: InGaAs cameras for 900-1700 nm range; liquid nitrogen-cooled InGaAs or other sensors for >1700 nm [2] [7].

- Spectral Filtering: Use long-pass filters (e.g., 1000 nm, 1200 nm, 1400 nm, 1500 nm LP) or band-pass filters to isolate specific windows [1].

- Image Analysis: Quantify resolution (FWHM of line profiles across vessels), SBR (target vs. background), and penetration depth (signal quality at depth).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for NIR-I/NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging Research

| Category | Specific Examples | Key Function/Application | Notable Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Fluorophores | PbS/CdS core-shell QDs [2] [1] | Tunable emission for multi-window comparison | Bright, size-tunable emission (1100->1700 nm); PEG coating for solubility |

| Ag₂S Quantum Dots [4] | NIR-II imaging; guided surgery | Low toxicity; emission ~1200 nm | |

| Organic Small Molecules | CH1055-PEG [5] | First aqueous NIR-II small-molecule dye | D-A-D architecture; ~90% renal excretion |

| IR-FGP, IR-FTAP [5] | High-performance NIR-II imaging | Systematic molecular engineering; improved quantum yield | |

| FDA-Approved & Clinical Dyes | Indocyanine Green (ICG) [5] [3] | Clinical NIR-I dye with NIR-II tail emission | FDA-approved; emits >1000 nm; used in first human NIR-II-guided surgery |

| IRDye800CW [5] | Clinical trial dye with NIR-II emission | Conjugatable; used in clinical trials | |

| Targeted Molecular Probes | EPH-3-DBS [6] | EphA2-targeted CRC imaging | Asymmetric cyanine scaffold; specific tumor targeting |

| CH1055-4Glu-AE105 [4] | uPAR-targeted glioma imaging | Peptide-targeted; delineates tumor margins | |

| Detection Equipment | InGaAs Cameras [7] | NIR-II (900-1700 nm) detection | Standard for NIR-II imaging; may require cooling |

| Spectrometers | Emission spectrum acquisition | Critical for characterizing fluorophore emission tails |

The strategic selection of optical imaging windows represents a critical factor in optimizing fluorescence bioimaging. While NIR-I imaging continues to provide value for certain applications, the NIR-II window consistently demonstrates superior performance through significantly reduced scattering, minimal autofluorescence, and enhanced penetration depth.

The emerging paradigm shift involves recognizing that regions with moderate water absorption (NIR-IIx, 1400-1500 nm; 1880-2080 nm) can be harnessed for high-contrast imaging rather than avoided. This refined understanding, coupled with continuous development of brighter fluorophores and more sensitive detectors, promises to further advance deep-tissue imaging capabilities for preclinical research and clinical translation.

In vivo fluorescence imaging is a powerful tool for biomedical research and clinical applications, yet its effectiveness is fundamentally governed by the interaction of light with biological tissues. The principal barriers to high-resolution deep-tissue imaging are photon absorption and scattering, both of which distort signal detection and degrade image quality. While absorption removes photons entirely from the detection pathway, scattering redirects photons, causing blurring and reducing the spatial information carried by each photon. Near-infrared (NIR) imaging has emerged as a solution to these challenges, with a significant performance leap observed when moving from the traditional NIR-I window (700-900 nm) to the NIR-II window (1000-1700 nm) and beyond. This transition capitalizes on a fundamental physical principle: scattering decreases substantially as wavelength increases. The reduced scattering of longer wavelengths minimizes photon diffusion, leading to unprecedented improvements in imaging resolution, contrast, and penetration depth. This review quantitatively compares the scattering advantages of longer wavelength imaging windows, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to guide imaging platform selection for specific applications.

The Physics of Light-Tissue Interactions

Scattering and Absorption Fundamentals

As photons travel through biological tissues, they encounter microscopic variations in refractive index from cellular structures, membranes, and organelles. These encounters cause photon scattering, which randomizes photon direction and blurs spatial information. The degree of scattering is inversely related to wavelength, following a power-law relationship approximately described as µs' ∝ λ^(-α), where the exponent α typically ranges between 0.2-4 for most biological tissues [5]. This inverse relationship means that longer wavelengths experience significantly less scattering than shorter wavelengths. Concurrently, photon absorption by chromophores such as hemoglobin, melanin, and water removes photons from the detection pathway. The combined effect of scattering and absorption determines the effective penetration depth and resolution achievable in biological imaging [8].

The Evolution of Biological Transparency Windows

The recognition of wavelength-dependent scattering has driven the exploration of successive biological transparency windows. The NIR-I window (700-900 nm) first provided advantages over visible light imaging, yet still experiences considerable scattering that limits resolution at depth. The NIR-II window (1000-1700 nm) demonstrates markedly reduced scattering and autofluorescence, enabling substantially improved imaging performance [5] [9]. Recent research has further subdivided the NIR-II window into NIR-IIa (1300-1400 nm), NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm), and NIR-IIc (1700-1880 nm) regions, with progressively improved scattering characteristics [2]. Most remarkably, investigations now extend beyond 1880 nm, where previously disregarded due to water absorption peaks, this region demonstrates exceptional imaging contrast attributable to the combined benefits of minimal scattering and strategic utilization of absorption properties [2].

Table 1: Characteristics of Near-Infrared Imaging Windows

| Imaging Window | Wavelength Range (nm) | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-I | 700-900 | Established fluorophores, FDA-approved agents (ICG) | Moderate scattering, limited penetration |

| NIR-II | 1000-1700 | Reduced scattering, minimal autofluorescence | Bright fluorophores needed for optimal performance |

| NIR-IIa | 1300-1400 | Enhanced resolution over NIR-I | - |

| NIR-IIb | 1500-1700 | Superior penetration depth | - |

| NIR-IIc | 1700-1880 | Further reduced scattering | - |

| 1880-2080 nm | 1880-2080 | Highest contrast from combined scattering/absorption effects | Requires bright probes to overcome water absorption |

Quantitative Comparison of Imaging Performance Across Wavelengths

Scattering Reduction and Resolution Enhancement

The theoretical foundation for reduced scattering at longer wavelengths translates directly into measurable improvements in imaging resolution and signal-to-background ratio (SBR). Monte Carlo simulations of photon transport through biological tissues quantitatively demonstrate these advantages across different spectral regions. When imaging identical structures, the NIR-IIx window (1400-1500 nm) and the 1880-2080 nm window produce simulated images with significantly higher SBR and structural similarity index measures (SSIM) compared to shorter NIR-II regions [2]. This improvement occurs because longer wavelengths experience less scattering, preserving ballistic photon paths that carry accurate spatial information. Additionally, in regions with higher water absorption (such as around 1930 nm), multiple scattered photons with longer path lengths are preferentially absorbed, further increasing the proportion of ballistic photons reaching the detector and thus enhancing image contrast [2].

Experimental validations consistently support these theoretical predictions. In vivo imaging of murine cerebral vasculature through intact scalp and skull demonstrates that NIR-II imaging provides substantially sharper anatomical features compared to NIR-I imaging [10]. This enhancement enables clear resolution of capillary networks and fine vascular structures that appear blurred or indistinguishable in NIR-I images. The improved resolution is quantifiable through metrics such as full width at half maximum (FWHM) measurements of point sources or line scans across vascular features, with NIR-II imaging typically achieving 1.5-2 times better resolution than NIR-I imaging at equivalent depths [5] [8].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics Across Wavelength Windows

| Wavelength Region | SBR Improvement vs NIR-I | Resolution Enhancement | Effective Penetration Depth |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-I (800 nm) | Baseline | Baseline | ~0.5-1 mm |

| NIR-II (1000-1350 nm) | 2-4 fold [5] | 1.5-2 fold [8] | 2-3 mm |

| NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm) | 3-5 fold [9] | 2-2.5 fold [8] | 3-4 mm |

| 1880-2080 nm | 4-6 fold [2] | >2.5 fold [2] | 4+ mm |

Penetration Depth and Signal-to-Background Ratio

The reduction in scattering at longer wavelengths directly enables greater imaging penetration depths. While NIR-I imaging typically achieves effective penetration of 0.5-1 mm in most tissues, NIR-II imaging extends this to 2-4 mm, with some applications reaching even greater depths [10] [8]. This enhanced penetration stems from both reduced scattering and lower tissue autofluorescence in the NIR-II window, which collectively improve the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) by 2-6 fold compared to NIR-I imaging [5] [2]. The superior SBR enables visualization of deeper structures and more precise delineation of anatomical features against the tissue background.

The relationship between wavelength and imaging performance exhibits a continuum of improvement rather than a binary transition. Within the NIR-II window itself, longer wavelengths generally provide progressively better performance, with the 1880-2080 nm window demonstrating exceptional contrast despite water absorption concerns [2]. This region benefits from the dual advantages of significantly reduced scattering due to wavelength redshifting and the beneficial filtering effect of water absorption on multiply scattered photons. When using sufficiently bright fluorophores such as PbS/CdS quantum dots, the 1880-2080 nm window produces high-contrast in vivo images with minimal background interference, particularly for scenarios with significant background signals from deeper tissue regions [2].

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Intravital Vascular Imaging

Cerebral vasculature imaging through intact skull provides a rigorous testbed for comparing scattering characteristics across wavelength windows. The Diffuse Optical Localization Imaging (DOLI) technique employs microdroplets containing NIR-II quantum dots (PbS/CdS) flowing through cerebral vasculature while being imaged with a short-wave infrared (SWIR) camera [10]. This approach demonstrates that high-resolution tracking of flowing particles can be maintained at depths up to 4 mm in tissue-mimicking phantoms, far exceeding the capabilities of conventional NIR-I imaging [10]. The localization precision achieved in these experiments directly results from reduced scattering of NIR-II photons, which minimizes blurring and maintains sharply defined point spread functions even in diffuse imaging regimes.

Diagram 1: DOLI Experimental Workflow for Cerebral Vasculature Imaging

Super-Resolution Imaging in the Diffuse Regime

The DOLI methodology represents a paradigm shift in high-resolution fluorescence imaging beyond the light diffusion limit. By treating each flowing microdroplet as an isolated point source and precisely localizing its position in a sequence of epi-fluorescence images, this technique achieves super-resolution imaging in the NIR-II window [10]. The fundamental enabler of this approach is the reduced scattering of NIR-II photons, which allows a significant proportion of photons to maintain their original direction despite traveling through thick, scattering tissues. Experimental protocols for DOLI involve:

Microdroplet Synthesis: Preparation of monodisperse toluene or dichloromethane droplets encapsulating PbS-based quantum dots with emission at 1400-1600 nm, using standard emulsification procedures with TWEEN20 surfactant [10].

Phantom Validation: System characterization using tissue-mimicking phantoms with Intralipid/agar layers of varying thickness (0-4 mm) to quantify resolution degradation with depth [10].

In Vivo Application: Intravenous injection of microdroplets into anesthetized mice followed by time-lapse image acquisition through intact scalp and skull using an InGaAs-based SWIR camera [10].

Localization Processing: Computational analysis of particle trajectories using ImageJ and custom algorithms to reconstruct vascular networks with exceptional detail [10].

This methodology successfully demonstrates that the reduced scattering of NIR-II wavelengths preserves localization accuracy below the diffraction limit, enabling detailed mapping of the murine cerebral vasculature without surgical cranial window installation [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for NIR-II Imaging Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Example Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | FDA-approved NIR-I dye with NIR-II emission tail | Clinical angiography, perfusion assessment | λabs = 805 nm, λem = 830 nm (in blood); long emission past 1500 nm [5] |

| IRDye800CW | Conjugatable NIR-I dye in clinical trials | Molecular imaging, targeted contrast | Significant NIR-II emission tail; currently in clinical trials [5] |

| CH1055-PEG | First aqueous NIR-II small-molecule dye | Vascular imaging, tumor targeting | D-A-D architecture; QY~0.03%; >90% renal excretion [5] |

| PbS/CdS Quantum Dots | Bright NIR-II fluorophores | Deep-tissue imaging, DOLI | Emission tunable (1100-1700 nm+); high brightness [10] [2] |

| SWCNTs (Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes) | Semiconducting NIR-II nanomaterials | In vivo biological imaging | Intrinsic NIR-II fluorescence; used in pioneering NIR-II studies [5] [11] |

| Donor-Acceptor-Donor (D-A-D) Dyes | Organic NIR-II fluorophores | High-resolution bioimaging | Systematic molecular tuning; emission 900-1600 nm [5] |

| InGaAs SWIR Cameras | NIR-II detection | Fluorescence image acquisition | Spectral range 900-1700 nm+; essential for NIR-II detection [10] |

Advanced Applications Exploiting the Scattering Advantage

Multiphoton microscopy represents another imaging modality that benefits from the scattering advantages of longer wavelengths. In conventional two-photon microscopy, near-infrared excitation (typically 700-1000 nm) generates fluorescence emission in the visible or NIR-I range. However, combining two-photon excitation with NIR-II emission detection creates a powerful synergy that maximizes penetration depth and resolution [12] [13]. The excitation photons in the NIR-I range experience reduced scattering during tissue penetration, while the emitted NIR-II photons further benefit from reduced scattering as they travel back to the detector. Recent characterization of Alexa Fluor dyes has revealed unexpected two-photon excitation peaks beyond 1000 nm, enabling simultaneous excitation of multiple fluorophores using single-wavelength illumination at approximately 1090 nm [12]. This approach provides improved photostability and enhanced fidelity of linear spectral unmixing at depth compared to shorter excitation wavelengths.

Diagram 2: Two-Photon Excitation Microscopy with NIR-II Detection

Imaging in Adipose Tissue and Other Challenging Environments

Different tissue types present unique scattering and absorption profiles that influence optimal window selection. Adipose tissue, with its distinct absorption characteristics and low scattering properties, demonstrates optimal imaging performance in the 1700-2080 nm window [2]. The unique lipid composition of adipose tissue creates absorption patterns that differ from water-dominated tissues, shifting the ideal imaging window toward longer wavelengths. Monte Carlo simulations and experimental validation confirm that this extended window provides superior imaging quality in adipose-rich environments due to the combined effects of moderate absorption and significantly reduced scattering [2]. These findings highlight the importance of matching imaging window selection to specific tissue environments, moving beyond the concept of a universal "best window" for all applications.

The scattering advantage offered by longer wavelengths represents a fundamental principle that continues to drive innovation in biological imaging. The progression from NIR-I to NIR-II imaging has already demonstrated substantial improvements in resolution, penetration depth, and signal-to-background ratio. Recent explorations beyond 1880 nm further reveal that strategic utilization of absorption properties, combined with minimal scattering, can produce exceptional imaging contrast. Future developments will likely focus on optimizing fluorophore brightness to capitalize on these extended windows, developing multimodal imaging systems that combine the strengths of multiple wavelength regions, and creating tissue-specific imaging protocols that account for unique scattering and absorption profiles. As these technologies mature, the scattering advantage of longer wavelengths will continue to expand the frontiers of in vivo biological observation, enabling researchers to visualize physiological processes with unprecedented clarity in intact, living systems.

Fluorescence imaging has become a cornerstone technology for in vivo visualization in biomedical research, enabling real-time, non-invasive observation of physiological processes with high spatial and temporal resolution. However, its effectiveness for deep-tissue imaging has been fundamentally limited by photon scattering and tissue autofluorescence within the visible (400-700 nm) and traditional near-infrared (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) spectral regions. These phenomena generate substantial background noise, severely compromising image contrast and resolution [14]. This comparison guide examines the paradigm shift toward the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm), where drastically reduced tissue autofluorescence enables unprecedented imaging clarity for research and drug development.

The core advantage of NIR-II imaging stems from fundamental light-tissue interactions. As wavelength increases, photon scattering decreases according to a λ-α relationship (where α typically ranges from 0.2-4 for most tissues) [5]. Furthermore, biological tissues contain far fewer endogenous fluorophores emitting in the NIR-II region, leading to significantly lower autofluorescence compared to the NIR-I window [14] [15]. This reduction in both scattering and autofluorescence substantially improves the signal-to-background ratio (SBR), which is the critical metric for image quality in deep-tissue imaging [2].

Quantitative Comparison: NIR-I vs. NIR-II Performance Metrics

Extensive experimental data demonstrates the superior performance of NIR-II imaging across multiple parameters. The following table summarizes key comparative metrics established through preclinical studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of NIR-I and NIR-II Imaging Performance

| Performance Parameter | NIR-I Window (700-900 nm) | NIR-II Window (1000-1700 nm) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Penetration Depth | 1-2 cm [14] | Several centimeters [14] [2] | Simulated and measured in murine models |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited by scattering (~10-100 μm) [14] | Micron-level at millimeter depth [14] [16] | Vascular imaging in mouse hindlimb |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) | Baseline [5] | ~2-4 fold higher than NIR-I [5] | Tumor imaging with targeted probes |

| Tissue Autofluorescence | High, problematic for gut and skin [15] | >2 orders of magnitude reduction [15] | Chow-fed mice with 670 nm excitation |

| Photon Scattering | Significant [14] | Significantly reduced [14] [2] | Theoretical models and experimental validation |

The data reveals that NIR-II imaging consistently outperforms NIR-I, particularly in scenarios requiring high contrast in deep tissues. The enhanced SBR is perhaps the most impactful advantage, as it directly translates to clearer delineation of anatomical structures and more precise identification of molecular targets.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Direct Visualization of Vasculature with NIR-II Probes

Protocol for High-Resolution Vascular Imaging:

- Probe Administration: Inject mice intravenously with a bolus of an NIR-II fluorescent probe (e.g., SWCNTs, Ag2S QDs, or organic dye CH1055-PEG).

- Image Acquisition: Under anesthetic, image the subject using an InGaAs camera optimized for the 1000-1700 nm range. Excitation is typically performed with an 808 nm laser.

- Data Analysis: Construct dynamic images from the acquired NIR-II fluorescence to visualize blood flow and vascular architecture with high spatiotemporal resolution [14] [5].

Results: Initial studies using single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) demonstrated the ability to resolve blood vessels with a spatial resolution of approximately ~10 μm and a temporal resolution of <300 ms, far surpassing what was achievable with NIR-I probes under identical conditions [14] [17]. The reduced scattering in the NIR-II window allowed for clear distinction of adjacent capillaries.

Systematic Analysis of Autofluorescence Reduction

Protocol for Quantifying Autofluorescence:

- Subject Preparation: Utilize mouse models fed either standard chow or a purified, alfalfa-free diet to control for dietary fluorophores [15].

- Multi-Wavelength Illumination: Illuminate subjects sequentially at different excitation wavelengths (e.g., 670 nm, 760 nm, 808 nm).

- Multi-Spectral Detection: Capture emission across different spectral bands (NIR-I: <975 nm; NIR-II: >1000 nm; NIR-II LP: >1250 nm) using a tunable imaging system like the IR VIVO preclinical imager (Photon, Etc.) [15].

- SBR Calculation: Calculate the SBR of a known contrast agent, such as liver-accumulated indocyanine green (ICG), across all imaging conditions.

Results: This rigorous protocol confirmed that autofluorescence is a major confounder in chow-fed mice under 670 nm excitation for NIR-I imaging. However, background autofluorescence was reduced by more than two orders of magnitude by switching to a purified diet, using longer excitation wavelengths (760 or 808 nm), and/or collecting NIR-II emission (>1000 nm) [15]. The combination of a purified diet and NIR-II imaging yielded the highest SBR, critical for identifying subtle features.

Diagram 1: The NIR-II Autofluorescence Reduction Mechanism. The core principle of NIR-II imaging is that reduced photon scattering and negligible tissue autofluorescence directly lead to a higher Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR), which is the foundation for superior image quality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful NIR-II imaging relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instrumentation. The table below details key solutions required for experiments in this field.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorophores | SWCNTs [14], Ag2S Quantum Dots [14] [17], CH1055-PEG [5], Rare Earth Nanoparticles [17] | Generate fluorescence within the NIR-II window. Choice depends on required brightness, emission peak, and biocompatibility. |

| Clinical Dyes (NIR-II Tails) | Indocyanine Green (ICG) [5], IRDye800CW [5] | FDA-approved or clinically trialed dyes whose long emission tails (>1000 nm) can be exploited for faster clinical translation. |

| Activation Probes | "Off-on-off" NIR-II probes (e.g., NDP [18]) | Designed for minimal background, activating only in target disease tissue (e.g., in response to H₂S) and deactivating upon exit. |

| Surface Coatings | Pluronic F-127 [16], PEGylation [8] | Enhance biocompatibility, water solubility, and circulation time of hydrophobic fluorophores; can reduce aggregation-caused quenching. |

| Imaging Instrumentation | InGaAs Cameras [14] [17] | Essential detectors for NIR-II light, as standard silicon-based CCDs have low quantum efficiency beyond 1000 nm. |

Advanced Probe Design and Emerging Sub-Windows

Molecular Engineering to Overcome Quenching

A significant challenge in NIR-II probe development is aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ), where fluorophores in close proximity undergo non-radiative decay, drastically reducing quantum yield (QY). Recent work on ring-fused fluorophores like 4F has provided insights into mitigating ACQ. By analyzing aggregate populations, researchers found that non-emissive dimers were primarily responsible for quenching. By implementing an aggregation control strategy to reduce dimer population, they created 4F NP3s—nanofluorophores with a NIR-II brightness of ~7,100 M⁻¹cm⁻¹, nearly five times greater than the clinical dye ICG [16].

Exploring New Imaging Windows Beyond 1500 nm

The conventional NIR-II window is being subdivided and extended to leverage specific optical properties. Notably, regions with higher water absorption, previously avoided, are now being exploited. The NIR-IIx (1400-1500 nm) and the newly proposed 1880-2080 nm windows benefit from the positive role of absorption: it preferentially attenuates multiple-scattered photons (which contribute to background blur) over ballistic signal photons, thereby further enhancing image contrast [2]. Simulation and experimental data confirm that these high-absorption windows can provide superior SBR and structural clarity compared to regions with lower absorption [2].

Diagram 2: NIR-II Probe Development Workflow. The journey to creating high-brightness NIR-II fluorophores involves identifying the root cause of emission quenching (like dominant dimer populations) and implementing targeted chemical strategies to mitigate it.

The collective evidence from optical simulations, controlled experiments, and advanced probe development solidifies the conclusion that NIR-II fluorescence imaging fundamentally overcomes the critical limitation of background noise that plagues NIR-I techniques. The drastic reduction of tissue autofluorescence, coupled with decreased photon scattering within the 1000-1700 nm window, provides a tangible and dramatic improvement in SBR, penetration depth, and spatial resolution. For researchers and drug development professionals, the transition to NIR-II methods and the selection of probes optimized for this window are no longer a matter of incremental gain but a strategic step toward achieving high-contrast, high-fidelity visualization in complex biological systems. The ongoing innovation in fluorophore chemistry and the exploration of new sub-windows promise to further elevate the capabilities of in vivo optical imaging.

Fluorescence imaging has become an indispensable tool for visualizing biological structures and physiological processes in biomedical research. For decades, the guiding principle in optical imaging has been to minimize light absorption by biological tissues, particularly by water, as it attenuates signal intensity. This conventional wisdom has directed researchers toward specific near-infrared windows, notably the first near-infrared window (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) and the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm) where water absorption is relatively low [5] [19]. However, recent groundbreaking research has challenged this fundamental assumption, revealing that water absorption, traditionally viewed as a detriment, can be strategically leveraged to enhance image contrast in deep tissue imaging [2].

This paradigm shift stems from a refined understanding of how absorption and scattering differentially affect image quality. While both phenomena reduce the number of photons reaching the detector, their effects on image formation are distinct. Scattering fundamentally blurs images by redirecting photons from their original paths, whereas absorption attenuates signal intensity without necessarily destroying spatial information [2]. This insight has led to the re-evaluation of spectral regions previously avoided due to strong water absorption, particularly around the ~1450 nm and ~1930 nm peaks, opening new possibilities for high-contrast fluorescence imaging in the NIR-II window and beyond [2] [8].

The implications of this discovery are profound for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on optical imaging for preclinical studies and surgical guidance. By understanding and exploiting the counterintuitive role of water absorption, imaging protocols can be optimized to achieve superior contrast, potentially revealing biological structures and processes that were previously obscured by background interference.

Theoretical Foundation: How Absorption Improves Contrast

The Physics of Light-Tissue Interactions

When photons travel through biological tissues, they encounter two primary interactions: scattering and absorption. Scattering events change the direction of photons, causing them to deviate from their original paths and creating a diffuse background that blurs the final image. Absorption, primarily by water and chromophores like hemoglobin and lipids, removes photons from the system entirely [2] [8]. The conventional view held that both processes were detrimental to image quality, but recent analysis reveals a more nuanced reality.

The critical insight is that multiple scattered photons travel longer paths through tissue compared to ballistic photons that maintain a straight trajectory from the source to the detector. When water absorption is significant, these multiply scattered photons have a higher probability of being absorbed due to their extended path lengths. Consequently, the relative proportion of ballistic photons that carry accurate spatial information increases at the detector, thereby improving the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) [2]. This phenomenon can be understood through the following relationship:

SBR ∝ (Iballistic / Iscattered) ∝ exp(μ_a × ΔL)

Where Iballistic represents ballistic photon intensity, Iscattered represents scattered photon intensity, μ_a is the absorption coefficient, and ΔL is the path length difference between scattered and ballistic photons. This equation demonstrates that increased absorption preferentially attenuates scattered photons with longer path lengths, enhancing the signal-to-background ratio.

Re-evaluating the Water Absorption Spectrum

Water, as the predominant component of biological tissues, exhibits characteristic absorption peaks at approximately 970 nm, 1200 nm, 1450 nm, and 1930 nm [2] [8]. The regions around these peaks were traditionally avoided in fluorescence imaging due to substantial signal attenuation. However, this perspective fails to consider the beneficial effect of absorption on image contrast.

Monte Carlo simulations of photon propagation through biological tissues have demonstrated that windows with moderate water absorption, specifically the NIR-IIx (1400-1500 nm) and the newly proposed 1880-2080 nm window, can produce images with higher SBR and structural similarity index measure (SSIM) compared to regions with lower water absorption [2]. The 1880-2080 nm window, situated around the strong water absorption peak at ~1930 nm, is particularly effective because it combines significant scattering suppression from wavelength redshift with the contrast-enhancing effect of water absorption [2].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental photon-tissue interactions and how water absorption preferentially attenuates scattered background signals:

Diagram: Water absorption preferentially attenuates scattered photons with longer path lengths, enhancing image contrast by reducing background signal.

Experimental Evidence: Validation in Biological Imaging

Monte Carlo Simulations and Theoretical Predictions

Computational modeling using Monte Carlo methods has been instrumental in predicting the advantages of high-absorption windows for fluorescence imaging. These simulations model photon propagation through biological tissues with realistic optical properties, allowing researchers to quantify expected image quality across different spectral regions without the constraints of current detector technology or probe availability [2].

In a seminal study, researchers simulated line source imaging across six NIR-II sub-windows: 1200-1300 nm, NIR-IIa (1300-1400 nm), NIR-IIx (1400-1500 nm), NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm), NIR-IIc (1700-1880 nm), and the proposed 1880-2080 nm window. The results demonstrated that the NIR-IIx and 1880-2080 nm windows produced images with significantly higher SBR and SSIM compared to other regions [2]. The 1880-2080 nm window showed particularly weak background interference, attributed to the combined effects of wavelength redshift and unique water absorption properties [2].

These simulations revealed a counterintuitive relationship: although absorption reduces total signal intensity, it disproportionately affects scattered photons that contribute to background noise. When sufficient signal intensity can be maintained through bright fluorophores or sensitive detectors, the contrast enhancement in high-absorption windows more than compensates for the overall signal reduction [2].

In Vivo Validation with Advanced Fluorophores

Experimental validation of this principle required the development of bright fluorophores with emission spectra in the high-absorption windows. Researchers employed water-soluble core-shell PbS/CdS quantum dots (QDs) with tunable emission peaks to objectively evaluate fluorescence imaging within various NIR windows [2]. These QDs were specifically engineered with four distinct emission maxima (1100 nm, 1300 nm, 1450 nm, and 1700 nm) to enable direct comparison of imaging performance across spectral regions [2].

In vivo experiments imaging mouse vasculature demonstrated that the 1880-2080 nm window provided exceptional contrast when using QDs with emission tails extending into this region. The high water absorption at these wavelengths effectively suppressed background signals from deeper tissues, which was particularly advantageous when imaging superficial structures above highly vascularized organs like the liver [2]. In these challenging scenarios, conventional NIR-II sub-windows struggled to distinguish target vessels from the strong background, while the 1880-2080 nm and NIR-IIx windows maintained clear visualization due to enhanced absorption [2].

Table 1: Comparison of NIR Imaging Windows Based on Monte Carlo Simulations and Experimental Data

| Imaging Window | Wavelength Range (nm) | Relative SBR | Relative SSIM | Key Characteristics | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-I | 700-900 | Low | Low | Moderate scattering, some autofluorescence | Clinical angiography with ICG |

| NIR-IIa | 1300-1400 | Medium | Medium | Reduced scattering vs NIR-I | General deep tissue imaging |

| NIR-IIx | 1400-1500 | High | High | Moderate water absorption enhances contrast | High-contrast vascular imaging |

| NIR-IIb | 1500-1700 | Medium-High | Medium-High | Low scattering, minimal absorption | Balanced performance imaging |

| NIR-IIc | 1700-1880 | Medium | Medium | Low scattering, rising absorption | Specialized applications |

| 1880-2080 nm | 1880-2080 | Very High | Very High | High water absorption maximizes contrast | Superficial structure imaging over bright backgrounds |

Multi-Channel Imaging Exploiting Absorption Differences

The positive role of absorption has further been exploited for multichannel bioimaging by leveraging the distinct absorption properties of different tissue types. For example, adipose tissue exhibits different absorption characteristics compared to other soft tissues, enabling the expansion of the optimal imaging window to 1700-2080 nm for applications involving fatty tissues [2]. This approach demonstrates how understanding the specific absorption profiles of different tissue components can guide selection of the optimal imaging window for particular biological contexts.

Researchers successfully performed simultaneous multi-channel imaging using both the 1880-2080 nm band and the NIR-IIx window, highlighting the potential for multiplexed imaging applications that exploit differential absorption effects [2]. This capability is particularly valuable for complex biological investigations requiring visualization of multiple targets or tissue types simultaneously.

Comparative Analysis: NIR-I vs. NIR-II Imaging Performance

The paradigm shift in understanding water absorption necessitates a re-evaluation of how we compare traditional NIR-I imaging with advanced NIR-II approaches. The following experimental data illustrates the performance differences between these modalities, accounting for both conventional low-absorption windows and the newly proposed high-absorption windows.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of NIR-I and NIR-II Imaging Performance for Vasculature Visualization

| Imaging Parameter | NIR-I (800 nm) | NIR-II (1300-1400 nm) | NIR-IIx (1400-1500 nm) | 1880-2080 nm Window |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~50 μm | ~20 μm | ~15 μm | ~10 μm |

| Penetration Depth | 1-3 mm | 3-8 mm | 2-6 mm | 1-4 mm |

| Tissue Autofluorescence | High | Low | Very Low | Negligible |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio | 1.5-2.5 | 3-5 | 5-8 | 8-12 |

| Vessel Contrast | Moderate | Good | Very Good | Excellent |

| Background Suppression | Limited | Good | Very Good | Exceptional |

The data reveals that while traditional NIR-II windows (1300-1400 nm) already offer significant improvements over NIR-I imaging, the strategic use of regions with higher water absorption (NIR-IIx and 1880-2080 nm) provides additional dramatic enhancements in image contrast, particularly for visualizing fine anatomical structures like capillaries [2] [19]. The trade-off for working in these high-absorption windows is potentially reduced penetration depth, making them ideally suited for applications where high contrast is prioritized over maximum depth.

Practical Implementation: Experimental Considerations

Research Reagent Solutions for High-Absorption Window Imaging

Transitioning to imaging in high-absorption windows requires specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for implementing this advanced imaging approach:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Absorption Window Fluorescence Imaging

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorophores | PbS/CdS QDs, Ag₂S QDs, CH1055-PEG dye, IR-FGP, IR-FTAP | Emission in NIR-II windows, particularly >1500 nm | High quantum yield, tunable emission, aqueous solubility |

| Surface Modification Agents | PEG derivatives, phospholipids, targeting ligands | Improve biocompatibility and targeting specificity | Enhanced circulation time, reduced immunogenicity |

| Reference Fluorophores | IR-26 | Quantum yield reference for NIR-II materials | Established reference standard (QY 0.05% in DMSO) |

| Tissue Phantoms | Intralipid, hemoglobin, agarose | System calibration and protocol validation | Simulate tissue scattering and absorption properties |

| Anaesthesia Equipment | Isoflurane systems, ketamine/xylazine | Maintain animal viability during in vivo imaging | Stable physiological conditions for prolonged imaging |

Experimental Protocol for High-Contrast NIR-II Imaging

Implementing high-contrast imaging in absorption-enhanced windows requires careful experimental design. The following workflow provides a standardized protocol for validating this approach:

Diagram: Experimental workflow for implementing high-contrast fluorescence imaging in water absorption-enhanced windows.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Fluorophore Selection and Preparation:

- Select fluorophores with sufficient brightness (quantum yield >5%) and emission extending beyond 1500 nm [2] [8]. PbS/CdS core-shell QDs have demonstrated particular effectiveness for the 1880-2080 nm window [2].

- Prepare fluorophore solutions at appropriate concentrations (typically 0.1-1 mg/mL in PBS) and ensure sterile filtration for in vivo applications.

System Calibration:

- Characterize the emission spectrum of the fluorophore using NIR spectrometers equipped with InGaAs detectors.

- Optimize excitation power and detector integration times to achieve sufficient signal while minimizing potential phototoxicity.

- Measure background autofluorescence in the target tissue regions without fluorophore administration.

Animal Preparation:

- Anesthetize animals according to institutional protocols (e.g., isoflurane maintenance at 1-2% in oxygen).

- Administer fluorophores via tail vein injection at optimized doses (typically 1-10 nmol for organic dyes).

- Position animals in the imaging system with temperature maintenance to ensure physiological stability.

Multi-Window Data Acquisition:

- Acquire sequential images across multiple NIR-II sub-windows (NIR-IIa, NIR-IIx, and 1880-2080 nm) using appropriate longpass filters.

- Maintain consistent imaging parameters (exposure, gain, FOV) across acquisitions for valid comparison.

- Include control images before fluorophore injection for background subtraction.

Quantitative Analysis:

- Calculate signal-to-background ratios for identical regions of interest across different spectral windows.

- Perform resolution measurements using line profiles across sharp anatomical features.

- Apply appropriate statistical tests to validate significance of contrast improvements (typically one-way ANOVA with post-hoc testing).

The re-evaluation of water absorption as a positive factor in fluorescence imaging represents a significant conceptual shift with far-reaching implications for biomedical research and drug development. By moving beyond the traditional avoidance of absorption peaks, researchers can now strategically select imaging windows that optimize contrast rather than simply maximizing signal intensity.

This paradigm shift enables unprecedented visualization of biological structures, particularly in scenarios with challenging backgrounds such as highly vascularized organs or adipose-rich tissues [2]. For drug development professionals, these advances translate to more accurate assessment of drug distribution, target engagement, and treatment response in preclinical models. The enhanced contrast facilitates more precise surgical guidance, potentially improving outcomes in oncological resection and vascular procedures.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on optimizing fluorophore brightness to further exploit high-absorption windows and developing multi-spectral imaging systems that can dynamically adapt to specific tissue environments. As these technologies mature, the counterintuitive role of water absorption may well become a fundamental principle in the design of next-generation optical imaging systems for biomedical applications.

Fluorescence imaging has become an indispensable tool for biomedical research, enabling real-time visualization of biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels. However, the effectiveness of this technology is fundamentally constrained by how deeply light can penetrate biological tissues and with what resolution. The competition between near-infrared imaging windows—specifically the first near-infrared window (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) and the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm)—represents a critical frontier in advancing preclinical and clinical imaging capabilities [20] [14]. While NIR-I fluorescence imaging has served as the workhorse for optical bioimaging for decades, its performance is ultimately limited by substantial photon scattering, significant tissue autofluorescence, and relatively shallow penetration depths that rarely exceed 1-2 mm in most tissues [14] [3]. The emergence of NIR-II fluorescence imaging has challenged these limitations by leveraging longer wavelengths that experience markedly reduced scattering and minimal autofluorescence, enabling penetration depths reaching several centimeters while maintaining micron-scale resolution [3] [21]. This comparison guide objectively examines the technical and performance distinctions between these imaging modalities through experimental data and practical implementation considerations, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate technologies for specific biomedical applications.

Technical Comparison: NIR-I vs. NIR-II Optical Properties

The differential performance between NIR-I and NIR-II imaging stems from fundamental interactions between light and biological tissues. As wavelength increases through the near-infrared spectrum, photon scattering decreases substantially while absorption characteristics exhibit more complex behavior influenced primarily by water, hemoglobin, and lipids [14] [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Optical Properties of NIR-I and NIR-II Windows

| Optical Property | NIR-I Window (700-900 nm) | NIR-II Window (1000-1700 nm) | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photon Scattering | Significant scattering | Markedly reduced scattering | NIR-II provides superior spatial resolution and clarity |

| Tissue Autofluorescence | High background levels | Minimal autofluorescence | NIR-II offers higher signal-to-background ratios |

| Water Absorption | Low absorption | Varies across sub-windows | Optimal sub-windows (1000-1350 nm) balance scattering and absorption |

| Penetration Depth | Typically 1-2 mm, up to 1-2 cm in ideal conditions | Several centimeters demonstrated | NIR-II enables deep-tissue imaging |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited by scattering effects | Micron-level resolution at millimeter depths | NIR-II reveals fine anatomical structures |

The signal-to-background ratio (SBR) represents a critical metric distinguishing these modalities. Research has demonstrated that the SBR of NIR-II imaging can be more than 100 times higher than that of NIR-I imaging when comparing quantum dot clusters emitting at 1,320 nm versus those emitting at 850 nm [14]. This dramatic improvement stems from significantly reduced autofluorescence and superior suppression of photon scattering in the NIR-II region [3] [21]. The penetration depth advantage of NIR-II imaging emerges from these favorable tissue-light interactions, with experimental evidence demonstrating visualization through several centimeters of tissue—a capability particularly valuable for whole-body imaging in small animals and potential clinical translation for human applications [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of NIR-I vs. NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging

| Performance Metric | NIR-I Imaging | NIR-II Imaging | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Depth | 1-2 cm maximum | Up to several centimeters | Cerebral vasculature imaging through intact scalp and skull [14] |

| Spatial Resolution | Diffraction-limited by scattering | Micron-level at millimeter depth | Visualization of fine capillary networks [3] |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio | Moderate (limited by autofluorescence) | High (>100x improvement possible) | Quantum dot studies showing dramatically improved SBR [14] |

| Tumor-to-Normal Tissue Ratio | ~2-3 | ~5-6 or higher | EGFR-targeted imaging in squamous cell carcinoma [21] |

| Vascular Imaging | Limited resolution of microvasculature | Clear delineation of blood vessels | Non-invasive mapping of cerebral vasculature [14] [21] |

Experimental Evidence: Key Studies and Methodologies

Preclinical Tumor Model Imaging

The superior performance of NIR-II imaging is particularly evident in oncology research, where precise tumor delineation is critical. In one representative study, researchers employed an EGFR-targeted NIR-II probe (CH1055-anti-EGFR) for human squamous cell carcinoma imaging in murine models [21]. The experimental protocol involved intravenous injection of the targeted contrast agent, followed by non-invasive imaging using an InGaAs camera system optimized for NIR-II detection. The results demonstrated a tumor-to-normal tissue ratio (T/NT) of approximately 5—significantly higher than what is typically achievable with NIR-I agents, which generally range between 2-3 [21]. This improved contrast enables more precise tumor margin delineation, potentially facilitating complete surgical resection while preserving healthy tissue.

Further advancing NIR-II molecular imaging, researchers developed organic small-molecule fluorophores with optimized S-D-A-D-S (shielding unit-donor-acceptor-donor-shielding unit) structures to enhance quantum yield and photostability [21]. One such probe, IR-BEMC6P, when conjugated to RGD peptides for targeting integrin receptors, achieved T/NT ratios around 6 in murine tumor models [21]. The methodology for these experiments typically involves: (1) synthesizing and functionalizing the NIR-II fluorophore with targeting ligands, (2) establishing tumor xenograft models, (3) intravenous administration of the probe, (4) longitudinal NIR-II imaging using InGaAs-based systems, and (5) ex vivo validation of probe distribution and target engagement.

Vascular Imaging and Perfusion Assessment

Cerebral and peripheral vasculature imaging provides another compelling demonstration of NIR-II advantages. The experimental approach typically utilizes non-targeted NIR-II fluorophores such as IRDye800CW, ICG, or specially designed NIR-II organic dyes that remain within the vascular compartment post-injection [5]. A key methodology involves tail vein injection in murine models followed by real-time dynamic imaging of cerebral blood flow using high-frame-rate NIR-II systems.

These studies consistently show that NIR-II imaging enables clear visualization of cerebral vasculature through the intact scalp and skull with resolution sufficient to distinguish individual vessels with diameters less than 20 μm [14] [21]. In comparison, NIR-I imaging of the same vascular networks suffers from considerable blurring and reduced contrast, particularly for deeper vessels. The quantitative analysis reveals that NIR-II imaging provides approximately 1.7-fold higher spatial resolution and 3-fold better contrast than NIR-I imaging at tissue depths exceeding 2 mm [21].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for NIR-II vascular imaging in preclinical models

Emerging Sub-Windows: NIR-IIb and Beyond

Recent investigations have explored specialized sub-windows within the NIR-II spectrum to further optimize imaging performance. The NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm) and NIR-IIx (1400-1500 nm) sub-windows have demonstrated exceptional imaging contrast despite previously being avoided due to water absorption peaks [2]. Counterintuitively, the moderate water absorption in these regions preferentially attenuates multiply scattered photons (which contribute to background) more than ballistic photons (which carry useful spatial information), thereby improving image quality [2].

Advanced experimental approaches now utilize bright fluorescent probes with emission beyond 1500 nm, such as specially engineered PbS/CdS quantum dots or organic dyes with extended conjugation [2]. The methodology involves: (1) synthesizing probes with tailored emission spectra, (2) characterizing optical properties using spectrophotometers with extended NIR detection, (3) performing comparative imaging across multiple spectral windows, and (4) quantifying performance metrics including spatial resolution, SBR, and penetration depth. These studies reveal that the 1700-2080 nm window provides optimal imaging quality in adipose-rich tissue environments due to unique absorption characteristics of lipids combined with significantly reduced scattering [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of NIR-I and NIR-II imaging requires specific reagents, instrumentation, and analytical tools. The following toolkit outlines core components for researchers entering this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for NIR-I/NIR-II Imaging

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-I Fluorophores | Indocyanine Green (ICG), IRDye800CW | Clinical and preclinical angiography, tumor imaging | FDA-approved (ICG), well-established protocols |

| NIR-II Organic Dyes | CH1055, FEB, LS-series dyes | Deep-tissue tumor imaging, vascular mapping | Renal clearance, modifiable for targeting |

| NIR-II Nanomaterials | PbS/CdS QDs, Ag₂S QDs, SWCNTs | High-resolution vascular imaging, theranostics | Potential long-term toxicity concerns |

| Targeting Moieties | RGD peptides, EGFR antibodies, affibodies | Molecular imaging of specific biomarkers | Conjugation chemistry, binding affinity |

| Imaging Systems | InGaAs cameras (NIR-II), Si-CCD (NIR-I) | Signal detection and image acquisition | Spectral sensitivity, cooling requirements, cost |

| Reference Standards | IR26 dye, custom phantoms | Quantum yield measurement, system calibration | Established reference values vary between labs |

Implementation Protocols: From Theory to Practice

NIR-II Image-Guided Surgery Protocol

The translational potential of NIR-II imaging is particularly evident in surgical oncology, where precise tumor margin delineation is critical. A comprehensive protocol for NIR-II fluorescence-guided tumor resection includes:

Preoperative Planning: Administer targeted NIR-II fluorescent probe (e.g., IR-BEMC6P@RGD) via intravenous injection 24 hours prior to surgery to allow for optimal target accumulation and background clearance [21].

Intraoperative Imaging: Employ a sterile NIR-II imaging system positioned 15-30 cm above the surgical field. Use 808 nm excitation at power densities of 10-100 mW/cm² (within safety limits) and acquire images using an InGaAs camera with appropriate long-pass filters (e.g., 1000 nm or 1200 nm cutoff) [20] [21].

Tumor Resection: Perform real-time visualization of tumor margins under NIR-II guidance, with periodic imaging to confirm complete resection. The high T/NT ratios (>5) achievable with NIR-II imaging provide clear visual guidance for distinguishing malignant from healthy tissue [21].

Margin Assessment: Excise tumor specimens and image ex vivo to quantify margin status. Comparative studies demonstrate that NIR-II imaging identifies positive margins that would be missed under NIR-I guidance or visual inspection alone [20].

Validation: Conduct histological analysis of resected tissues to correlate fluorescence signals with pathological findings, establishing sensitivity and specificity of the approach.

This protocol was successfully implemented in a clinical study involving 23 patients with primary and metastatic liver cancer, where NIR-II imaging with ICG (utilizing its NIR-II tail emission) significantly improved tumor identification and boundary delineation compared to conventional NIR-I imaging [3].

Quantitative Comparison Methodology

For researchers conducting direct comparisons between NIR-I and NIR-II imaging performance, the following standardized methodology is recommended:

Phantom Preparation: Create tissue-simulating phantoms using Intralipid suspensions (1-2% for scattering) with added India ink (for absorption) to mimic tissue optical properties. Embed capillary tubes filled with fluorophores at varying depths (1-10 mm).

Dual-Modality Imaging: Image identical phantoms or animal preparations using both NIR-I (Si-CCD) and NIR-II (InGaAs) systems with matched field of view, spatial calibration, and illumination geometry.

Image Analysis: Quantify key parameters including:

- Spatial Resolution: Measure edge spread function or full-width at half-maximum of line profiles across sharp features.

- Signal-to-Background Ratio: Calculate as mean signal intensity in region of interest divided by mean background intensity.

- Penetration Depth: Determine maximum depth at which structures remain distinguishable from background.

- Contrast-to-Noise Ratio: Compute as (signal mean - background mean)/background standard deviation.

Statistical Comparison: Perform paired t-tests or ANOVA with post-hoc testing to determine significant differences between imaging modalities, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Figure 2: Photon-tissue interactions showing ballistic versus scattered photons

The comprehensive comparison between NIR-I and NIR-II fluorescence imaging reveals a consistent pattern of superior performance for NIR-II technologies across multiple metrics including penetration depth, spatial resolution, and signal-to-background ratio. While NIR-I imaging remains valuable for specific clinical applications (particularly those utilizing FDA-approved agents like ICG), NIR-II imaging demonstrates clear advantages for preclinical research and emerging clinical applications requiring deep-tissue visualization with high spatial fidelity.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) creating brighter and more specific NIR-II organic fluorophores with optimal pharmacokinetics, (2) advancing imaging hardware to make NIR-II systems more accessible and cost-effective, (3) establishing standardized protocols and validation methods for quantitative NIR-II imaging, and (4) expanding clinical translation of NIR-II technologies through targeted contrast agents and optimized surgical guidance systems. As these advancements materialize, the penetration depth showdown between NIR-I and NIR-II imaging will increasingly favor NIR-II technologies for demanding biomedical applications where millimeter-to-centimeter imaging depth and micron-scale resolution are paramount.

Toolkit for the Future: NIR-II Fluorophores and Cutting-Edge Applications

Fluorescence imaging has become an indispensable tool in biomedical research and clinical practice, enabling real-time visualization of physiological and pathological processes. However, traditional imaging in the visible (400-700 nm) and first near-infrared (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) windows faces fundamental limitations due to significant light scattering, tissue autofluorescence, and absorption by biological components, resulting in limited penetration depth (typically 1-2 mm for visible light and 1-6 mm for NIR-I) and suboptimal spatial resolution [14] [22]. These constraints have motivated the exploration of the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm), where reduced photon scattering, minimal tissue autofluorescence, and lower light absorption enable superior imaging performance with deeper tissue penetration (up to several centimeters) and micron-scale resolution [23] [3].

The core thesis of NIR-II imaging research posits that leveraging the 1000-1700 nm spectral region fundamentally outperforms NIR-I imaging by providing enhanced spatial resolution and tissue contrast through reduced scattering phenomena. This advantage stems from the inverse relationship between scattering and wavelength, where longer wavelengths experience significantly less scattering in biological tissues [8] [24]. Table 1 quantitatively compares the fundamental properties of NIR-I and NIR-II imaging windows, highlighting the superior characteristics of NIR-II light.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of NIR-I vs. NIR-II Imaging Performance

| Parameter | NIR-I (700-900 nm) | NIR-II (1000-1700 nm) | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Penetration Depth | 1-6 mm [22] | Up to 20 mm [22] | Mouse tissue phantom studies [24] |

| Tissue Scattering | High | 4-10x reduction vs. NIR-I [3] | Resolution test chart imaging [2] |

| Autofluorescence | Significant | Minimal to negligible [14] | In vivo mouse imaging [14] |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited at depth | Micron-scale at millimeter depths [8] | Vasculature imaging in mice [23] |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) | Low (~1.3-2.2) [24] | High (3.3-10.5) [24] | Mouse lymph vessel imaging [24] |

| Maximum Permissible Exposure | Standard | Higher safety limits [25] | Laser safety standards [25] |

The development of NIR-II fluorophores has progressed rapidly, yielding diverse materials with distinct photophysical properties and biomedical applications. This review systematically compares the leading NIR-II fluorophore classes—inorganic nanomaterials, organic small molecules, and hybrid systems—providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to guide probe selection for specific applications.

The NIR-II Fluorophore Arsenal: Materials and Properties

Inorganic Nanomaterials

Inorganic nanomaterials represent the foundational class of NIR-II fluorophores, characterized by high photostability and tunable optical properties.

Table 2: Comparison of Inorganic NIR-II Nanomaterials

| Material Type | Emission Range (nm) | Quantum Yield | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Dots (Ag₂S, PbS/CdS) | 950-1700 [2] [22] | High (varies by composition) [22] | Broad excitation, narrow emission, superior quantum yield [23] | Potential toxicity, long-term retention [23] [3] |

| Rare-Earth-Doped Nanoparticles (RENPs) | 1000-1600 [26] [22] | Variable (low to moderate) [23] | Large Stokes shifts, no photobleaching, narrow emission peaks [26] [22] | Low quantum yield, unknown long-term toxicity [23] |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | 1000-1600 [14] [22] | Low [23] | Good photostability, large Stokes shift [22] | Low quantum yield, high excitation intensity required [23] |

| Metal Nanoclusters (Au, Au/Cu) | NIR-I to NIR-II [22] | Moderate | Excellent biocompatibility, renal clearable size [22] | Relatively newer class, properties under investigation [22] |

Quantum dots (QDs), particularly Ag₂S and core-shell PbS/CdS structures, exhibit bright emission with high quantum yields and size-tunable properties [2] [22]. Rare-earth-doped nanoparticles (RENPs) feature unique electronic transitions between 4f orbitals that generate large Stokes shifts, minimal photobleaching, and narrow emission bands [26] [22]. Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) were among the first materials used for in vivo NIR-II imaging, offering inherent fluorescence across 1000-1600 nm, though their low quantum yield remains a limitation [14] [23]. Metal nanoclusters, particularly gold-based formulations, provide excellent biocompatibility and renal clearance potential, emerging as promising candidates for clinical translation [22].

Organic Small-Molecule Fluorophores

Organic small-molecule fluorophores offer distinct advantages for clinical translation, including predictable metabolic clearance, synthetic versatility, and superior biocompatibility compared to inorganic nanomaterials [3].

Table 3: Comparison of Organic NIR-II Small-Molecule Fluorophores

| Molecular Architecture | Emission Range (nm) | Molecular Weight (Da) | Stokes Shift (nm) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor-Acceptor-Donor (D-A-D) | 1000-1200 [3] | >500 typical | Large (up to 582) [27] | Tunable ICT, high molar extinction coefficient [3] |

| Cyanine Derivatives | 800-1100 [3] | <500 achievable | Moderate | Structural flexibility, commercial availability [27] |

| GFP Chromophore-Based (LS Series) | 444-1218 [27] | 226-449 [27] | Up to 566 [27] | Low molecular weight, tunable emission [27] |

| BODIPY Derivatives | NIR-I to NIR-II [25] | Variable | Small to moderate | High quantum yield in NIR-I, modular synthesis [25] |

The donor-acceptor-donor (D-A-D) architecture represents a prominent design strategy, featuring an electron-deficient core (acceptor) flanked by electron-rich groups (donors) connected through π-conjugated bridges. This structure promotes intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), effectively reducing the energy gap and enabling NIR-II emission [3]. Cyanines, classical dye structures with polymethine chains, offer structural flexibility for emission tuning into the NIR-II window [3]. A groundbreaking approach reported in 2025 introduced the LS series of fluorophores based on modified green fluorescent protein (GFP) chromophores, achieving emission beyond 1200 nm with molecular weights under 500 Da by regulating Coulomb attraction interactions rather than traditional bandgap reduction [27].

Organic/Inorganic Nanohybrids

Organic/inorganic nanohybrids integrate the advantages of both material classes, combining the biocompatibility and metabolic clearance of organic components with the superior optical properties and stability of inorganic nanomaterials [24]. These systems enable sophisticated functions including energy transfer, J-aggregate formation, and stimulus-responsive imaging, permitting the development of activatable probes that enhance imaging specificity [24].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Validation

Synthesis of PbS/CdS Core-Shell Quantum Dots for NIR-II Imaging

Protocol Objective: Synthesis of water-soluble PbS/CdS core-shell quantum dots with emission at 1700 nm for deep-tissue imaging [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Lead oxide (PbO), elemental sulfur (S), oleic acid, 1-octadecene

- Cadmium oxide (CdO), hexamethyldisilathiane

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based ligands

Experimental Procedure:

- PbS Core Synthesis: Heat PbO, oleic acid, and 1-octadecene to 150°C under argon to form lead oleate. Inject sulfur precursor rapidly at 120°C and grow nanocrystals for 1-5 minutes [2].

- CdS Shell Growth: Purify PbS cores and transfer to cadmium oleate solution at 100°C. Slowly inject sulfur precursor for controlled shell growth [2].

- Water Solubilization: Ligand exchange with PEG derivatives to achieve aqueous compatibility [2].

- Characterization: Confirm core-shell structure via transmission electron microscopy. Measure absorption and emission spectra using NIR spectrophotometer and InGaAs detector [2].

Key Performance Metrics: The resulting PbS/CdS QDs exhibit bright fluorescence at 1700 nm with significantly improved photostability compared to bare PbS cores, enabling high-contrast in vivo imaging in the 1880-2080 nm window [2].

In Vivo Vascular Imaging in Mouse Model

Protocol Objective: High-resolution visualization of murine vasculature using NIR-II imaging [23].

Materials:

- Animal Model: Healthy nude mice

- Imaging Agent: ICG or other NIR-II fluorophore

- Equipment: NIR-II imaging system with 808 nm laser, InGaAs camera

Experimental Workflow:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize mouse and place on heated stage.

- Contrast Administration: Intravenously inject 100-200 μL of fluorophore solution.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire time-series images at 100-500 ms exposure using 808 nm excitation.

- Data Analysis: Quantify signal-to-background ratio (SBR) and resolution at different wavelengths.

Diagram 1: In vivo NIR-II vascular imaging workflow

Expected Outcomes: NIR-II imaging typically achieves SBR values of 3.3-10.5 in murine vasculature, significantly exceeding the 1.3-2.2 range typical of NIR-I imaging [24]. Resolution of 20-30 μm can be achieved for blood vessels located several millimeters deep [23].

Detection of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer's Disease Model

Protocol Objective: Real-time NIR-II fluorescent detection of deposited Aβ proteins in brains of living Alzheimer's disease mouse models [27].

Materials:

- Animal Model: Transgenic Alzheimer's disease mice

- Imaging Agent: LS7 dye (GFP chromophore-based NIR-II fluorophore)

- Equipment: NIR-II confocal microscope

Experimental Procedure:

- Dye Screening: Screen LS dye library for specificity toward Aβ42 fibrils in vitro.

- Validation: Confirm 22.7-fold fluorescence increase upon Aβ binding in vitro [27].

- In Vivo Imaging: Intraven administer LS7 dye and acquire NIR-II images through thinned skull.

- Histological Correlation: Sacrifice animals for brain sectioning and immunohistochemistry validation.

Results: The optimized NIR-II dye LS7 demonstrated selective binding to Aβ42 fibrils, enabling real-time imaging of deposited amyloid proteins in mouse brains with high specificity [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorophores | CH1055 [25], LS series [27], PbS/CdS QDs [2], Ag₂S QDs [22] | Contrast generation | Varies by type; see Tables 2 & 3 |

| Surface Modifiers | PEG derivatives [2], phospholipids [22] | Biocompatibility enhancement | Improves water solubility, circulation time |

| Targeting Ligands | Peptides, antibodies, aptamers [3] | Molecular targeting | Enables specific biomarker recognition |