Overcoming Penetration Depth Limits in Fluorescence Imaging: From NIR Probes to Clinical Solutions

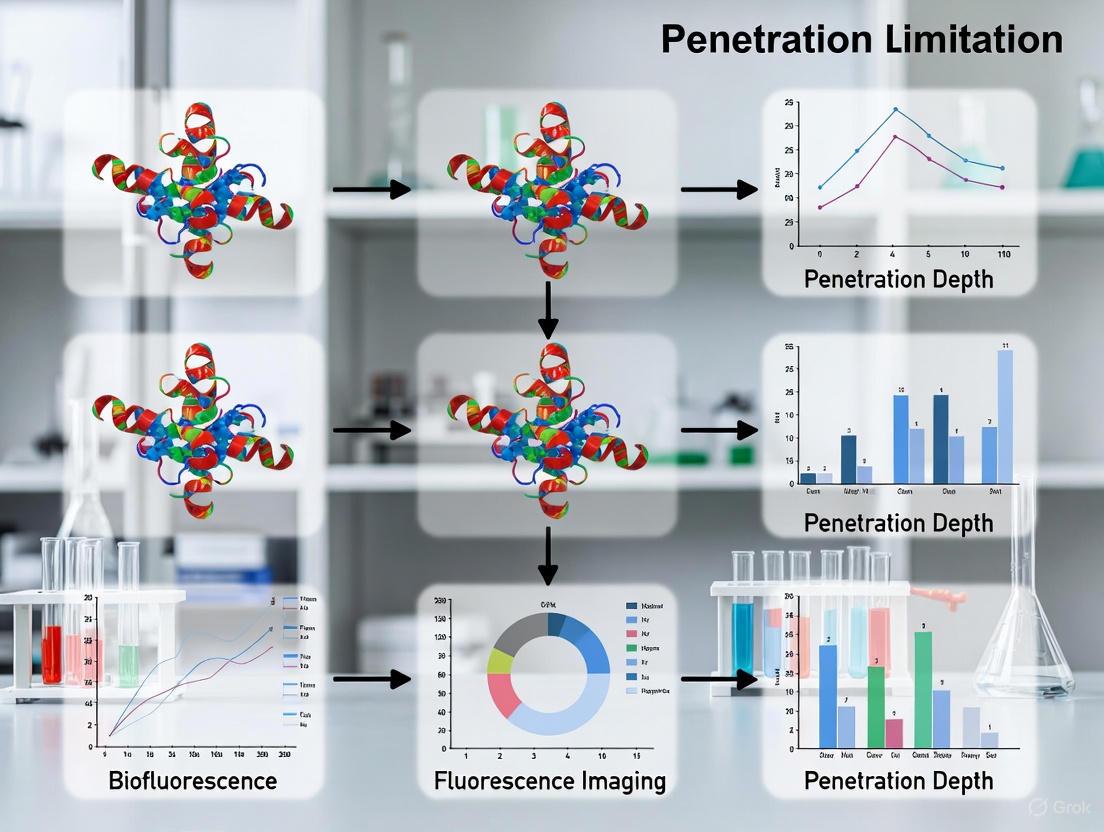

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the penetration depth limitations inherent to fluorescence imaging, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals.

Overcoming Penetration Depth Limits in Fluorescence Imaging: From NIR Probes to Clinical Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the penetration depth limitations inherent to fluorescence imaging, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational physics of light-tissue interactions, including scattering and absorption, which constrain imaging depth and resolution. The review covers methodological breakthroughs, such as imaging in the Second Near-Infrared (NIR-II) window and the development of novel fluorophores, which significantly enhance signal-to-background ratios. We also detail practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, from advanced denoising algorithms to probe design, that improve imaging efficacy in deep tissues. Finally, a comparative analysis validates these solutions against established clinical standards, assessing their potential for translation into areas like image-guided surgery and therapeutic monitoring. The synthesized insights aim to guide the strategic implementation of fluorescence imaging technologies in preclinical and clinical research.

The Physics of Light in Tissue: Understanding the Core Barriers to Deep Imaging

Fundamental Principles of Fluorescence and Signal Generation

Core Principles of Fluorescence

What is the fundamental process behind fluorescence generation?

Fluorescence is a three-stage process that occurs in molecules known as fluorophores or fluorescent dyes [1]:

- Excitation: A fluorophore absorbs a photon of light from an external source (e.g., a lamp or laser), elevating it to a higher-energy excited electronic state (Sâ‚´) [1].

- Excited-State Lifetime: The fluorophore resides in the excited state for a short time (typically 1–10 nanoseconds). During this period, it undergoes conformational changes and interacts with its environment, losing some energy and relaxing to a lower vibrational state (Sâ‚) [1].

- Emission: The fluorophore returns to its ground state (Sâ‚€) by emitting a photon of light. Because energy was lost during the excited-state lifetime, this emitted photon has lower energy and a longer wavelength than the excitation photon. This difference in wavelength is known as the Stokes Shift [1].

The Stokes shift is crucial for sensitivity, as it allows the emission light to be distinguished from the excitation light [1].

Diagram of the fluorescence process (Jablonski diagram).

What are the key spectroscopic properties of a fluorophore?

The performance of a fluorescent probe is defined by several key properties, summarized in the table below [1].

| Property | Definition | Significance in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Spectrum | Plot of excitation wavelength vs. number of fluorescence photons generated [1]. | Determines the optimal wavelength of light needed to excite the fluorophore most efficiently [1]. |

| Emission Spectrum | Plot of emission wavelength vs. number of fluorescence photons generated [1]. | Used to select the appropriate emission filter for detection and is the basis for multiplexing different fluorophores [1]. |

| Extinction Coefficient (EC) | Measure of a fluorophore's ability to absorb light at a specific wavelength [1]. | The "brightness" of a fluorophore is proportional to the product of its EC and its Quantum Yield [1]. |

| Fluorescence Quantum Yield (QY) | Ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed [1]. | A measure of the efficiency of the fluorescence process; a higher QY indicates a brighter probe [1]. |

| Stokes Shift | The energy/wavelength difference between the peak excitation and peak emission [1]. | A larger Stokes shift makes it easier to separate the emission signal from scattered excitation light, reducing background [1]. |

| Photobleaching | The irreversible destruction of a fluorophore upon prolonged exposure to excitation light [1]. | Limits the duration over which a sample can be imaged. Can be mitigated by reducing light exposure and using antifade reagents [2] [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Why is my fluorescence signal weak or absent?

Weak or absent signal is a common issue with several potential causes and solutions [2].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No or Weak Staining | Primary antibody not validated for the application [2]. | Confirm species reactivity and check supplier data for application validation. Use a positive control [2]. |

| Antibody concentration is too low [2]. | Perform a titration experiment to find the optimal antibody concentration [2]. | |

| Intracellular target not accessible for surface staining [2]. | Check antibody epitope location; perform intracellular staining if the target is inside the cell [2]. | |

| Fluorophore is photobleaching [2]. | Use an antifade mounting medium, reduce light exposure during imaging, and choose photostable dyes (e.g., rhodamine-based) [2] [3]. | |

| Incorrect imaging settings [2]. | Verify that the microscope's excitation and emission filters are correctly set for the dye being used [2]. |

How can I reduce high background or non-specific staining?

Excessive background can obscure specific signals. The following table outlines common remedies [2].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background | Cell or tissue autofluorescence [2]. | Use an unstained control to assess autofluorescence. Avoid blue fluorescent dyes for low-expression targets, as autofluorescence is high in blue wavelengths. Use autofluorescence quenchers [2]. |

| Non-specific binding of secondary antibody [2]. | Include a secondary-only staining control. Use highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies and ensure blocking buffers are compatible (e.g., avoid goat serum when using anti-goat secondaries) [2]. | |

| Antibody concentration is too high [2]. | Titrate the antibody to find a concentration that provides strong specific signal with low background [2]. | |

| Insufficient washing [2]. | Increase the number and volume of washes during the staining procedure [2]. |

What can I do if my fluorescence images are blurry or have uneven illumination?

Image quality issues often relate to the microscope's optical components and setup [3] [4].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Image Quality | Dirty objective lens [3]. | Clean the lens gently with a lens cleaning cloth and an appropriate solvent (e.g., absolute ethanol), using compressed gas to remove dust first [3]. |

| Coverslip of incorrect thickness [3]. | Use high-quality coverslips with a thickness (e.g., 0.17 mm) matched to the microscope objective's correction [3]. | |

| Vignetting or uneven illumination [4]. | Center and align the light source. Increase the image overlap percentage during slide scanning or use background correction software [4]. | |

| Sample drift or out-of-focus areas [4]. | Allow the microscope to thermally stabilize for at least 2 hours before imaging. Add more focus points to the focus map for slide scanning [4]. | |

| Photobleaching between adjacent tiles [4]. | Optimize tissue preparation for fluorophore stability. Reduce exposure time and illumination intensity where possible [4]. |

How does penetration depth limit fluorescence imaging, and what are the emerging solutions?

The penetration depth of high-resolution fluorescence imaging is fundamentally limited by the scattering and absorption of light by biological tissues [5] [6]. This is a central challenge in preclinical and clinical imaging.

Fundamental Limitation: Tissue scatters light strongly, preventing it from being focused deep within tissue. Consequently, techniques like standard confocal microscopy are limited to superficial depths (sub-millimeter), while techniques that can image deeper (e.g., diffuse optical tomography) suffer from poor spatial resolution (millimeters) [6].

Solutions and Advanced Methodologies:

- Near-Infrared (NIR) Imaging: Light in the near-infrared windows (NIR-I: 650-950 nm; NIR-II: 1000-1700 nm) experiences less scattering and absorption than visible light, allowing for greater penetration and higher resolution at depth [5] [7].

- Protocol Insight: A state-of-the-art approach uses biocompatible quantum dots emitting in the NIR-IIc window (1700-2000 nm) with superconducting single-photon detectors. This setup has enabled non-invasive confocal imaging through an intact mouse head to a depth of ~1,100 μm, allowing single-cell resolution in lymph nodes without surgery [7].

- Ultrasound-Switchable Fluorescence (USF): This technique breaks the acoustic diffraction limit to achieve high resolution in deep tissue.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Contrast Agent Synthesis: Environment-sensitive NIR dyes (e.g., ICG) are encapsulated into thermo-sensitive nanoparticles (e.g., made of PNIPAM polymer) [6].

- Switching Mechanism: A focused ultrasound beam locally heats a tiny volume within the tissue. When the temperature crosses the nanoparticle's lower critical solution temperature (LCST), it undergoes a phase transition, changing the dye's microenvironment and dramatically boosting its fluorescence (switching it "ON") [6].

- Image Acquisition: The ultrasound focus is raster-scanned across the sample. Only the fluorescence from the switched-on voxel is detected, building a high-resolution image point-by-point. This method is not susceptible to dynamic processes in tissue, unlike some other deep-imaging techniques [6].

- Experimental Workflow:

Workflow of Ultrasound-Switchable Fluorescence (USF) imaging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) | Enable labeling and tracking of specific proteins or structures in live cells through genetic fusion. They are the most common fluorophores for live-cell imaging [8]. |

| Organic Dyes (e.g., Cyanine Dyes, CF Dyes) | Synthetic fluorescent molecules often used for immunostaining, flow cytometry, and in vivo imaging. They offer high brightness and photostability [2] [1]. |

| Near-Infrared II (NIR-II) Dyes and Quantum Dots | Fluorophores emitting in the 1000-1700 nm range. They minimize light scattering and autofluorescence, enabling deep-tissue imaging with high spatial resolution [5] [7]. |

| Antifade Mounting Medium | A reagent used to slow down photobleaching in fixed samples prepared for microscopy, preserving fluorescence signal during prolonged observation [2] [3]. |

| Autofluorescence Quenchers (e.g., TrueBlack) | Used to chemically suppress the intrinsic fluorescence of tissues or cells, thereby improving the signal-to-background ratio in an experiment [2]. |

| Ultrasound-Switchable Contrast Agents | Thermo-sensitive nanoparticles encapsulating a dye (e.g., ICG). Their fluorescence is activated by localized ultrasound heating, facilitating high-resolution imaging deep within tissue [6]. |

| Blocking Buffers | Solutions containing proteins (e.g., BSA) or sera used to cover non-specific binding sites on a sample, reducing background staining in immunofluorescence [2]. |

| Acetylexidonin | Acetylexidonin, MF:C26H34O9, MW:490.5 g/mol |

| 3-Epichromolaenide | [(6Z,10Z)-9-acetyloxy-6,10-dimethyl-3-methylidene-2-oxo-3a,4,5,8,9,11a-hexahydrocyclodeca[b]furan-4-yl] (E)-4-hydroxy-2-methylbut-2-enoate |

FAQs: Understanding Penetration Depth

What are the fundamental optical phenomena that limit penetration depth in tissues? The primary limitations are due to absorption and scattering [9]. Absorption occurs when tissue components like hemoglobin, water, or melanin take up light energy, preventing its deeper propagation [9] [10]. Scattering refers to the deflection of light from its original path by tissue components, causing the light to diffuse and reducing the amount that travels straight into the tissue [9] [11]. These two phenomena work together to attenuate light, and penetration depth is defined as the depth at which the light's intensity inside the material falls to about 37% (1/e) of its original surface value [12].

How does the choice of wavelength affect imaging depth? Tissue absorption and scattering are strongly dependent on wavelength. In general, longer wavelengths in the near-infrared (NIR) region penetrate deeper because key tissue chromophores like hemoglobin and water have lower absorption in these ranges, and scattering is reduced [9] [10]. The table below summarizes how different wavelength windows perform.

| Wavelength Window | Wavelength Range | Key Characteristics & Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Visible | 400 - 700 nm | High scattering and absorption by hemoglobin and melanin; shallow penetration [9] [10]. |

| NIR-I | 700 - 900 nm | Reduced scattering and absorption compared to visible light; better penetration; used by FDA-approved dyes like ICG [10]. |

| NIR-II | 1000 - 1700 nm | Significantly reduced scattering, absorption, and autofluorescence; enables deepest penetration and highest resolution for in vivo imaging [10]. |

| Water Absorption Peaks | ~970 nm, 1200 nm, 1450 nm | Regions of high absorption by water, which can limit penetration and must be considered when selecting wavelengths [9] [10]. |

What are the observable consequences of absorption and scattering during an experiment? In imaging techniques like Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM), absorption creates "shadow" or "stripe" artifacts [13]. These appear as dark regions in the image where absorbing structures (e.g., pigmented cells) have blocked the excitation light path or the emitted fluorescence on its way to the detector [13]. More generally, attenuation leads to a dimming of the fluorescence signal, a lower signal-to-noise ratio, and can completely obscure structures located deep within or behind attenuating regions [14] [11].

Besides wavelength selection, what strategies can help overcome depth barriers? Several methodological and computational strategies can mitigate depth limitations:

- Chemical Clearing: Treating tissues with chemical clearing agents reduces scattering by matching the refractive indices of different tissue components [13].

- Multi-View Imaging: Acquiring images from multiple angles and computationally merging them can "see around" absorbing structures that would otherwise cast shadows in a single view [13].

- Computational Attenuation Correction: Techniques like OPTiSPIM use a transmission scan to create a 3D map of the sample's attenuation properties, which is then used to computationally correct the shadows in the fluorescence image [13].

- Advanced Fluorophores: Using bright, photostable fluorophores with high quantum yield in the NIR-II window, such as certain quantum dots or novel organic dyes, provides a stronger signal that is less affected by attenuation [10] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Shadow Artifacts in Thick Samples

Issue: Your fluorescence images of thick or mesoscopic samples (e.g., embryos, cleared tissues) show dark shadows or stripes, making it difficult to see the true fluorescence distribution [13].

Explanation: These shadows are attenuation artifacts caused by absorbing materials (e.g., pigment, densely packed cells) in the sample. They affect both the incoming excitation light and the outgoing emitted light [13].

Solutions:

- Strategy: Multi-view Imaging

- Protocol: Image your sample from at least two opposing angles (e.g., 0° and 180°). For more complex samples, acquire multiple views (e.g., every 90° or 120°). Use computational fusion software to combine these views into a single, artifact-reduced image [13].

- Rationale: A structure that is hidden by a shadow in one view may be fully visible in another. Combining these views provides a more complete picture.

- Strategy: Attenuation Correction with Transmission Data

- Protocol:

- Perform a transmission scan of your sample using Optical Projection Tomography (OPT) to measure the 3D distribution of the attenuation coefficient (α) [13].

- Acquire your standard fluorescence image (e.g., via LSFM).

- For each voxel in your fluorescence image, calculate a correction factor based on the Beer-Lambert law. This involves computing the path integral of the attenuation coefficient from the illumination source to the voxel, and from the voxel to the detector, accounting for the detection cone [13].

- Apply the correction factor to each voxel to generate a corrected fluorescence image.

- Rationale: This method directly measures and computationally reverses the physical effects of absorption.

- Protocol:

Diagram: Troubleshooting shadow artifacts in imaging.

Problem: Inadequate Penetration Depth for Deep-Tissue Imaging

Issue: The fluorescence signal from your target structure is too weak or cannot be detected because it is located deep (e.g., >500 µm) within scattering tissue.

Explanation: The excitation light and emitted fluorescence are severely attenuated by scattering and absorption as they travel through tissue. This is the central "depth barrier" in fluorescence imaging [14] [10].

Solutions:

- Strategy: Shift to NIR-II Imaging

- Protocol:

- Select or synthesize a fluorophore with excitation and emission in the NIR-II window (1000-1700 nm) [10].

- Use an imaging system equipped with lasers and detectors (e.g., InGaAs cameras) sensitive in this wavelength range.

- Adjust your optical filters and objectives to be optimized for NIR-II light.

- Rationale: Scattering of light is reduced at longer wavelengths, and tissue autofluorescence is minimal, resulting in deeper penetration and a higher signal-to-background ratio [10].

- Protocol:

- Strategy: Use Multiphoton Microscopy with SWIR Wavelengths

- Protocol:

- Label your sample with fluorophores having high multiphoton cross-sections, such as quantum dots (QDs) designed for infrared emission [15].

- Use a long-wavelength (e.g., 1300 nm or 1650 nm) short-wave infrared (SWIR) ultrafast laser for excitation in a multiphoton microscope [15].

- For large-area imaging, implement a temporal focusing setup to achieve axial resolution while using SWIR excitation [15].

- Rationale: Longer SWIR wavelengths experience less scattering in tissue. Multiphoton excitation provides inherent optical sectioning, and temporal filling allows parallel imaging of a large plane. QDs provide the high brightness needed for efficient excitation under these conditions [15].

- Protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials used to address penetration depth challenges in fluorescence imaging research.

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function |

|---|---|

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | An FDA-approved NIR-I fluorescent dye (emission ~900 nm) used for clinical applications like surgical navigation and vascular imaging [14] [10]. |

| NIR-II Organic Dyes | Synthetic fluorescent molecules engineered to emit in the 1000-1700 nm range, offering deeper penetration and reduced scattering compared to visible or NIR-I dyes [10]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Semiconductor nanoparticles with size-tunable emission, high brightness, and large multiphoton cross-sections. Ideal for deep-tissue imaging with NIR-II or SWIR excitation [15]. |

| Chemical Clearing Agents | Chemicals (e.g., Scale, CUBIC) that render tissues transparent by reducing light scattering, thereby improving penetration and image clarity [13]. |

| BODIPY Dyes | Versatile fluorescent probes with high quantum yields and photostability. Their emission can be tuned across 500-700 nm, and they can be conjugated to targeting moieties for specific imaging [14]. |

| Songoroside A | Songoroside A, MF:C35H56O7, MW:588.8 g/mol |

| Marsformoxide B | Marsformoxide B, MF:C32H50O3, MW:482.7 g/mol |

Understanding Autofluorescence and Its Impact on Penetration Depth

What is autofluorescence and why is it a problem in fluorescence imaging?

Autofluorescence (AF) is the natural emission of light from biological structures when excited with specific wavelengths of light, without the application of any exogenous fluorescent markers [16] [17]. This phenomenon originates from endogenous fluorophores present in tissues and cells, including NAD(P)H, flavins, collagen, elastin, lipofuscins, and aromatic amino acids like tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine [16] [17].

In the context of fluorescence imaging solutions research, autofluorescence creates a significant problem by reducing signal-to-background ratio, which ultimately limits effective penetration depth and obscures specific signals from targeted fluorophores [18] [19] [20]. When excitation light travels through tissue to reach fluorescent markers at depth, it simultaneously excites autofluorescence throughout the entire optical path. This creates a background "haze" that masks the specific signal of interest [18]. As imaging depth increases, this problem becomes more pronounced because the desired signal from deeper targets undergoes greater attenuation due to both absorption and scattering, while autofluorescence continues to be generated from superficial layers [18] [21].

Table 1: Common Endogenous Fluorophores and Their Spectral Properties

| Fluorophore | Excitation Peak (nm) | Emission Peak (nm) | Primary Biological Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H | 340 | 450-470 | Cytoplasm, mitochondria |

| Flavins | 450-490 | 520-560 | Mitochondria |

| Collagen | 330-370 | 400-450 | Extracellular matrix |

| Elastin | 350-420 | 420-510 | Extracellular matrix |

| Lipofuscin | 410-470 | 500-695 | Lysosomal deposits |

| Tryptophan | 280 | 300-350 | Proteins |

| Keratin | 700-760 (2-photon) | 445-580 | Epithelial cells, hair [22] |

The relationship between autofluorescence and penetration depth limitations follows an exponential decay pattern, where the detectable specific signal decreases dramatically with depth due to the competing autofluorescence background [18]. Research has demonstrated that without proper management of autofluorescence, the practical penetration depth for fluorescence imaging can be limited to as little as 1-2 mm, whereas with optimized techniques, detection up to 6 mm or more may be achievable [21].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

How can I identify if autofluorescence is affecting my imaging results?

Perform control experiments with unlabeled samples to establish baseline autofluorescence levels [23]. This is the most direct method to identify autofluorescence contributions. Additionally, spectral lambda scanning can help characterize the autofluorescence profile of your specific sample [19]. If you observe signal in channels where no fluorophore should be emitting, or if you notice unexpectedly high background that reduces image contrast, autofluorescence is likely a factor.

Key indicators of autofluorescence problems:

- Signal persists in "no dye" control samples [23]

- High, uniform background across the entire field of view

- Poor signal-to-background ratio despite adequate labeling

- Signal bleed-through in multiple detection channels

- Unusual fluorescence in samples fixed with aldehydes [16]

What are the most effective strategies to reduce autofluorescence in biological samples?

Optimize sample preparation to minimize autofluorescence sources [19] [20]. For live-cell imaging, replace standard culture media with phenol red-free medium or clear buffered saline solutions, as phenol red and other media components can be highly fluorescent [19] [20]. For fixed samples, consider alternatives to aldehyde-based fixatives like formalin and glutaraldehyde, which can generate fluorescent condensation products [19]. Chemical treatments with sodium borohydride or Sudan black B can attenuate existing autofluorescence in stored samples [19].

Strategic fluorophore selection is crucial—choose fluorescent probes with excitation and emission spectra that minimize spectral overlap with your sample's autofluorescence profile [19]. Modern synthetic dyes like Alexa Fluor, Dylight, or Atto dyes are preferable as they tend to be brighter, more stable, and have narrower excitation/emission bands [19]. When possible, select far-red fluorescent dyes because autofluorescence is typically stronger in the blue and green regions of the spectrum [19] [20].

Instrument optimization can significantly reduce autofluorescence impact. Use spectral detection systems to precisely define collection windows that exclude autofluorescence peaks [19]. For systems with white light lasers, fine-tune excitation wavelengths to maximize specific signal while minimizing autofluorescence excitation [19].

How does autofluorescence specifically limit penetration depth in fluorescence imaging?

Autofluorescence limits penetration depth by creating a background floor that obscures weak signals from deeper structures [18] [24]. As excitation light travels to reach fluorophores at depth, it generates autofluorescence throughout the entire optical path. The emitted fluorescence from deep targets must then travel back through tissue, undergoing additional attenuation. The combined effect of signal attenuation and constant autofluorescence background reduces the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) for deeper targets [18]. When the CNR falls below a detection threshold of approximately 3, the target becomes undetectable [18].

Table 2: Depth Detection Limits Under Various Conditions

| Condition | Typical Detection Limit | Primary Limiting Factors |

|---|---|---|

| High autofluorescence background | 1-2 mm | Strong superficial AF, absorption by blood |

| Optimized near-infrared imaging | 4-6 mm | Reduced scattering/absorption in NIR [18] [21] |

| Multiple fluorescent sources | 2-3 mm | Signal crosstalk, overlapping emissions [21] |

| Through highly absorbing media (blood) | <1 mm | Strong absorption of visible light [18] |

| Through highly scattering media | 2-4 mm | Loss of signal directionality [18] |

What advanced techniques can help overcome autofluorescence limitations?

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) can differentiate specific signals from autofluorescence based on their distinct fluorescence decay characteristics, even when their emission spectra overlap [19] [22]. This technique is particularly powerful because while autofluorescence and specific fluorophores may share similar emission spectra, their fluorescence lifetimes (typically on the nanosecond scale) often differ significantly [19].

Multispectral imaging approaches allow mathematical separation of signal components based on their complete spectral signatures rather than single emission peaks [17]. This enables more sophisticated unmixing of specific fluorescence from autofluorescence background.

Two-photon excitation provides inherent optical sectioning and can reduce out-of-focus autofluorescence by limiting excitation to a small focal volume [22]. However, it's important to note that two-photon excitation can also excite additional endogenous fluorophores that aren't accessible with single-photon excitation [22].

Photobleaching of autofluorescence before adding specific fluorophores can be an effective strategy [19]. By exposing samples to high-intensity light prior to imaging, endogenous fluorophores can be selectively bleached, reducing their contribution to background during actual data acquisition.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Establishing Autofluorescence Baseline and Spectral Profiling

Purpose: To characterize the autofluorescence signature of your specific sample system as a critical first step in addressing penetration depth limitations.

Materials:

- Unlabeled control samples (identical preparation without fluorescent dyes)

- Fluorescence microscope with spectral detection capability

- Identical imaging dishes/media as used in experimental samples

Procedure:

- Prepare unlabeled control samples using identical protocols as experimental samples, omitting only the fluorescent dyes or markers [23].

- Image control samples using the same acquisition settings (exposure time, gain, excitation wavelengths) planned for experimental samples.

- Perform spectral lambda scanning across the entire emission range relevant to your experimental fluorophores [19].

- Document the autofluorescence intensity levels and spectral profile for each sample type.

- Use this baseline to optimize filter sets and detection windows for experimental imaging.

Expected Results: Autofluorescence profiles will vary significantly by tissue type, fixation method, and imaging media. Tissues rich in collagen/elastin typically show strong autofluorescence in the 400-500 nm range [16] [17].

Protocol 2: Fluorophore Titration for Optimal Signal-to-Background Ratio

Purpose: To determine the optimal concentration of fluorescent dyes that maximizes specific signal while minimizing nonspecific background.

Materials:

- Fluorescent dye stock solutions

- Labeled samples

- Wash buffers (e.g., PBS)

Procedure:

- Prepare a dilution series of your fluorescent dye covering concentrations both below and above the manufacturer's recommendation [19] [20].

- Label separate sample aliquots with each concentration using otherwise identical protocols.

- Perform thorough washing (2-3 times with buffered saline) after labeling to remove unbound dye [20].

- Image all samples using identical acquisition parameters.

- Quantify both specific signal intensity and background autofluorescence for each concentration.

Expected Results: There will be an optimal concentration range that maximizes the signal-to-background ratio. Too low concentrations yield weak specific signal; too high concentrations increase nonspecific binding and background [20].

Protocol 3: Chemical Reduction of Autofluorescence in Fixed Samples

Purpose: To reduce existing autofluorescence in stored or fixed samples using chemical treatments.

Materials:

- Fixed tissue samples or cells

- Sodium borohydride solution (1 mg/mL in PBS) or Sudan black B (0.1-0.3% in 70% ethanol)

- Staining containers

- Wash buffers

Procedure:

- After fixation and before immunolabeling, incubate samples with sodium borohydride solution for 10-30 minutes [19].

- Alternatively, treat samples with Sudan black B solution for 20-30 minutes [19].

- Wash samples thoroughly with buffer before proceeding with standard labeling protocols.

- Compare treated samples with untreated controls to assess autofluorescence reduction.

Expected Results: Sodium borohydride specifically reduces aldehyde-induced autofluorescence, while Sudan black B quenches broad-spectrum autofluorescence, particularly from lipofuscin-like pigments [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Autofluorescence Management

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phenol red-free media | Reduces media autofluorescence | Essential for live-cell imaging; contains necessary nutrients without fluorescent pH indicator [19] [20] |

| Sodium borohydride | Chemical reduction of aldehyde-induced AF | Particularly effective for samples fixed with formaldehyde or glutaraldehyde [19] |

| Sudan black B | Broad-spectrum autofluorescence quenching | Effective against lipofuscin and other autofluorescent pigments [19] |

| Far-red fluorescent dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647) | Spectral separation from AF | AF is typically weaker in far-red region; enables deeper penetration [19] [21] |

| Glass-bottom imaging dishes | Reduce substrate autofluorescence | Plastic dishes exhibit strong autofluorescence; glass provides lower background [20] |

| Modern synthetic dyes (Alexa Fluor, Dylight, Atto) | Bright, stable, specific labeling | Narrow emission bands facilitate separation from AF; higher quantum yield improves detection [19] |

| Mounting media with antifade reagents | Preserve fluorescence, reduce bleaching | Prolongs signal stability during extended imaging sessions |

| F9170 | F9170, MF:C100H135N21O22, MW:1983.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Ketodoxapram-d4 | 2-Ketodoxapram-d4, MF:C24H28N2O3, MW:396.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Methodologies for Depth Resolution

How can I quantitatively characterize my system's depth sensitivity?

Use tissue-simulating optical phantoms with well-characterized materials and fluorescent contrast agents to evaluate imaging system performance [18]. These phantoms incorporate obscuring layers of tissue-mimicking material above a uniform fluorescent layer, allowing systematic quantification of depth detection capabilities.

Depth sensitivity characterization protocol:

- Image tissue-equivalent depth targets under typical operating conditions (working distance, ambient lighting, system settings) [18].

- Measure pixel intensity for each well with varying thickness of scattering/absorbing material above fluorescent layer.

- Plot mean pixel intensity versus tissue-equivalent depth.

- Fit data to an exponential equation to estimate fluorescence signal at any depth.

- Calculate contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), where CNR ≥ 3 is typically considered the limit of detection [18].

This systematic approach allows researchers to establish the practical penetration depth limits of their specific imaging system and optimize parameters for deep-tissue applications.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: How can I minimize photobleaching and phototoxicity during live-cell fluorescence imaging?

- Reduce Light Exposure: Use lower light intensities, shorter exposure times, and activate illumination only during image acquisition using fast shutters [25] [26].

- Use Near-Infrared (NIR) Fluorophores: NIR light is less energetic, experiences less scatter and absorption in tissue, and is therefore less damaging to cells and provides better depth penetration [21] [18] [26].

- Employ Antifading Reagents: Add antifading reagents to your mounting medium to slow the photobleaching process [2] [3].

- Choose Stable Dyes: Select photostable fluorescent dyes, such as rhodamine-based dyes, and avoid those known to bleach quickly, like some blue fluorescent dyes [2].

- Utilize Sensitive Detection Systems: Use cameras with high quantum efficiency (QE) and confocal systems designed for fast, low-light imaging to capture sufficient signal with minimal light input [26].

Q2: What are the main causes of low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) when imaging deep tissues, and how can I improve it?

- Causes: Light is attenuated by absorption (e.g., by blood) and scattering as it travels through tissue, which dims the signal. Autofluorescence and optical system limitations contribute to background noise [21] [2] [18].

- Solutions:

- Optimize Your System: Use high-numerical aperture (NA) objective lenses to gather more light and ensure they are clean and properly corrected. Oil-immersion objectives can minimize light loss [3].

- Increase Signal Generation: Ensure your fluorophore is bright and used at an optimal concentration. For low-expression targets, use signal amplification methods like indirect immunofluorescence or tyramide signal amplification (TSA) [25] [2].

- Suppress Background: Use blocking agents designed for fluorescent applications to reduce non-specific binding. Quench tissue autofluorescence with products like TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher, especially when working in blue wavelengths [2].

Q3: My fluorescence signal is faint or absent. What should I check?

- Confirm Antibody and Dye Validity: Ensure your primary antibody is validated for your specific application (e.g., immunofluorescence) and that it is used at an appropriate concentration. Perform a titration to find the optimal dilution [2].

- Check Target Accessibility: For intracellular targets, confirm that your staining protocol makes the epitope accessible (e.g., through permeabilization). Verify that the antibody binds to an extracellular domain for cell surface staining [2].

- Verify Imaging Settings: Use the correct excitation and emission filters for your dye. Remember that far-red dyes like Alexa Fluor 647 must be detected with a camera and are not visible by eye [2].

- Assess Photobleaching: If the signal was present but faded quickly, your sample may have undergone photobleaching. Implement the strategies listed in Q1 [2] [26].

Q4: How can I characterize my imaging system's depth sensitivity? You can characterize depth sensitivity using tissue-simulating optical phantoms [21] [18]. The general protocol is:

- Acquire Images: Image a phantom with a uniform fluorescent layer buried at progressively deeper levels of tissue-mimicking material under your standard operating conditions [18].

- Measure Intensity: For each depth, measure the mean fluorescence pixel intensity within a region of interest [18].

- Plot and Analyze: Plot the normalized intensity versus depth. The depth at which the signal drops below a detectable level (e.g., where the contrast-to-noise ratio, CNR, falls below 3) is your system's limit of detection [18].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background | Tissue autofluorescence | Use autofluorescence quenchers; switch to red/NIR dyes [2]. |

| Non-specific antibody binding | Titrate antibody concentration; use highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies [2]. | |

| Insufficient washing | Increase wash frequency and volume [2]. | |

| Photobleaching | Excessive light exposure | Reduce intensity/exposure time; add antifade reagent [2] [26]. |

| Unstable fluorophore | Choose a more photostable dye (e.g., rhodamine-based) [2]. | |

| Low Signal in Deep Tissue | Signal attenuation | Use NIR fluorophores; optimize imaging system sensitivity [21] [18] [26]. |

| Fluorophore concentration too low | Increase concentration if possible; use signal amplification techniques [21] [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterizing Depth Sensitivity Using Tissue-Mimicking Phantoms This methodology allows you to quantify how well your fluorescence imaging system can detect signals at different depths [21] [18].

Materials:

Procedure: a. Place the phantom at the standard working distance for your imaging system. b. Under typical imaging conditions (e.g., standard exposure time, gain, ambient lighting), acquire fluorescence images of the phantom [18]. c. For each well or region representing a different depth, measure the mean pixel intensity within a central region of interest (ROI) that covers about half the diameter of the well [18]. d. Calculate the Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) for each depth if required. A CNR of 3 is typically considered the limit of detection [18]. e. Plot the normalized mean intensity (or CNR) versus the depth of the tissue-mimicking material. f. Fit an exponential curve to the data to model signal attenuation and estimate the detection limit for your system [18].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Live-Cell Imaging This protocol provides steps to maximize signal while preserving cell health [25] [26].

Materials:

Procedure: a. Minimize Photodamage: * Use the lowest light intensity and shortest exposure time that yield a usable signal. * Utilize a system with "active blanking" to ensure the light source is only on during camera exposure [26]. * Consider using a multi-point scanning confocal system, which distributes light exposure more efficiently than point scanners [26]. b. Maximize Signal Capture: * Use an objective lens with high numerical aperture (NA) and optimal chromatic correction [3]. * For dim samples, use a camera with high QE (>80%) to detect more photons [26]. c. Validate Cell Health: Throughout the experiment, monitor cells for signs of phototoxicity such as membrane blebbing, vacuolation, or cessation of division [25] [26].

Table 1: Optical Properties of Biological Tissues and Phantom Components This table summarizes key parameters that affect light propagation in tissues, as used in experimental phantoms [21].

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range in Brain Tissue [21] | Common Phantom Components [21] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Coefficient (µa) | Likelihood of light being absorbed per unit distance. | 0.001 to 0.05 mmâ»Â¹ | metHb (methemoglobin) |

| Reduced Scattering Coefficient (µs') | Likelihood of light being scattered per unit distance, accounting for forward direction. | 0.5 to 2.5 mmâ»Â¹ | Intralipid |

| Anisotropy (g) | Measure of forward scattering tendency. | 0.80 to 0.95 [18] | Not typically specified in phantom studies |

Table 2: Depth Estimation Techniques for Fluorescent Inclusions A summary of algorithms for estimating the depth of a fluorescent object based on reflectance and fluorescence measurements [21].

| Technique | Input Parameters | Calculation of Slope (m) for Depth Estimation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Diffusion Equation Solution | µa, µs' (optical properties) | ( m = \frac{1}{\delta{\lambda2}} - \frac{1}{\delta{\lambda1}} ) where ( \delta{\lambda} = \sqrt{\frac{D}{\mua}} ), ( D = \frac{1}{3(\mua + \mus')} ) | Requires precise knowledge of optical properties [21]. |

| 2. Empirical Scattering Correction | µs', Diffuse Reflectance (Rd) | ( m = \frac{ \ln \left( \frac{Rd{\lambda1}}{Rd{\lambda2}} \right) }{ \mu_s'(\text{700 nm}) \times 3.28 } ) | Requires knowledge of reduced scattering coefficient [21]. |

| 3. Diffuse Reflectance Correction | Diffuse Reflectance (Rd) only | ( m = \ln \left( \frac{Rd{\lambda1}}{Rd{\lambda2}} \right) ) | Simpler but may be less accurate for some optical properties [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647) | A biochemically stable near-infrared fluorescent dye used in phantoms to simulate fluorophores like PpIX due to its similar emission when excited at 635 nm [21]. |

| metHb (Methemoglobin) | A stable form of hemoglobin used in phantoms to simulate the absorption properties of blood in tissue [21]. |

| Intralipid | A fat emulsion used in optical phantoms to simulate the scattering properties of biological tissues [21]. |

| TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher | A reagent used to suppress tissue autofluorescence, a major source of background noise, particularly in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [2]. |

| EverBrite Mounting Medium | An antifade mounting medium that helps preserve fluorescence signal and reduce photobleaching during microscopy [2]. |

| Tungsten Halogen Lamp | A broadband white light source used for acquiring diffuse reflectance images, which are necessary for calibrating and correcting fluorescence depth measurements [21]. |

| Liquid Crystal Tunable Filter (LCTF) | A wavelength filter placed in front of a camera that allows for the sequential acquisition of spectral images at specific, narrow wavelength bands [21]. |

| Deferoxamine-DBCO | Deferoxamine-DBCO, MF:C44H61N7O10, MW:848.0 g/mol |

| CTB probe-1 | CTB probe-1, MF:C46H60N10O8S2, MW:945.2 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow and System Diagrams

Systematic Troubleshooting Approach

Depth Sensitivity Characterization Workflow

Multimodal Strategy for Imaging Challenges

Breakthrough Imaging Windows and Advanced Fluorophores for Enhanced Penetration

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my in vivo fluorescence signal weak and background high despite using an NIR-I dye?

Problem: Weak target signal and high background autofluorescence in deep-tissue imaging.

Explanation: In the traditional NIR-I window (700–900 nm), photon scattering remains significant, and biological tissues exhibit noticeable autofluorescence. Although superior to visible light, NIR-I penetration depth is practically limited to about 0.2 mm in brain tissue, for instance [27]. Scattering distorts the signal path and reduces the number of ballistic photons that can be collected, while autofluorescence from biomolecules creates a competing background noise.

Solution:

- Transition to NIR-II Imaging: Shift your imaging and detection to the NIR-II window (1000–1700 nm). The reduced photon scattering (scaling with λ-α) and minimal tissue autofluorescence in this region significantly enhance the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) [28] [29].

- Leverage "Off-Peak" Imaging: If your equipment is limited to NIR-I fluorophores like Indocyanine Green (ICG) or IRDye800CW, try detecting their long emission tails in the NIR-II region (e.g., using a 1500 nm long-pass filter). This "off-peak" method can provide some of the benefits of NIR-II imaging with clinically available dyes [29].

- Verify Probe Brightness: Ensure your fluorescent probe has sufficient brightness to overcome the inherent signal attenuation over longer path lengths. For NIR-II, this may require bright inorganic nanomaterials or novel organic dyes with high quantum yields [30] [27].

FAQ 2: My NIR-II fluorescent probes lack target specificity and show poor biocompatibility. How can this be improved?

Problem: Non-specific probe accumulation and potential long-term toxicity.

Explanation: Many high-performance NIR-II probes, particularly inorganic nanomaterials like quantum dots and rare-earth-doped nanoparticles, face challenges in biodegradability and can have potential long-term toxicity [30]. Furthermore, complex synthesis processes can hinder functionalization for specific targeting.

Solution:

- Employ Organic Dyes and Surface Engineering: Utilize organic small-molecule NIR-II dyes (e.g., those with a donor-acceptor-donor (D-A-D) structure), which generally have better renal clearance profiles [29]. For inorganic probes, implement surface modifications with polymers (like PEG) or targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) to enhance biocompatibility, improve water solubility, and confer active targeting capabilities [30] [27].

- Develop Activatable Probes: Design "smart" probes that remain fluorescently "off" until they encounter a disease-specific biomarker (e.g., enzymes, pH, reactive oxygen species). This strategy dramatically reduces background signal from non-target tissues and improves imaging specificity [30] [31]. The "off-on-off" probe design is a advanced example that further minimizes background upon probe clearance from normal tissues [31].

FAQ 3: How can I achieve precise imaging of brain tumors considering the blood-brain barrier?

Problem: The blood-brain barrier (BBB) prevents efficient delivery of imaging probes to glioblastoma (GBM) and other brain tumors.

Explanation: The BBB is a major obstacle for diagnostic and therapeutic agents. Conventional probes cannot cross this barrier, leading to poor imaging contrast for brain diseases [27].

Solution:

- Utilize Targeted Nanoplatforms: Develop NIR-II nanoprobes functionalized with ligands that can undergo receptor-mediated transcytosis to cross the BBB [27].

- Multimodal Imaging Guidance: Use NIR-II fluorescence imaging in conjunction with other techniques like MRI to guide and validate the delivery of probes across the BBB [27].

- Explore Passive Targeting: Leverage the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, which allows nanoparticles of a certain size to accumulate preferentially in tumor tissues due to their leaky vasculature, although this is less effective for intact BBB [32].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging for In Vivo Tumor Detection and Photothermal Therapy

This protocol outlines the use of NIR-II AIE dots for imaging-guided photothermal ablation of lesions, such as endometriosis [32].

Workflow Diagram:

Materials:

- NIR-II AIE Dots: Aggregation-induced emission luminogens with emission in 1000-1700 nm [32].

- Animal Disease Model: e.g., murine model of endometriosis or glioblastoma [32] [27].

- NIR-II Imaging System: Includes an 808 nm laser for excitation and an InGaAs camera for detection in the 1000-1700 nm range [32] [28].

- Histology Reagents: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for post-treatment validation [32].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Probe Preparation: Synthesize and characterize AIE dots. Ensure they exhibit high fluorescence brightness in the NIR-II window and a photothermal conversion efficiency sufficient for therapy (e.g., ~40%) [32].

- Animal Administration: Intravenously inject the AIE dots into the animal model via the tail vein.

- Passive Accumulation: Allow sufficient time (e.g., several hours to a day) for the nanoparticles to accumulate at the tumor/lesion site through the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect [32].

- NIR-II Imaging: Anesthetize the animal and position it under the NIR-II imaging system. Excite the probe with an 808 nm laser and collect the emitted fluorescence using the InGaAs camera. Acquire high-resolution images to locate the lesion.

- Photothermal Therapy: Once the lesion is located, increase the power density of the 808 nm laser at the target site. Maintain irradiation until the local temperature reaches the required ablation threshold (e.g., 50°C) for the necessary duration to induce cell death [32].

- Validation: Sacrifice the animal and extract the target tissue. Perform H&E staining and immunofluorescence analysis to confirm the histological reduction of the lesion post-therapy [32].

Protocol 2: Evaluating NIR-II "Off-On-Off" Probes for High-Contrast Molecular Imaging

This protocol details the use of advanced activatable probes for sensitive imaging of early-stage diseases with minimal background [31].

Signaling Pathway Diagram:

Materials:

- "Off-On-Off" Probe (NDP): A naphthalene diimide-based probe that is activated by a specific biomarker (e.g., Hâ‚‚S) and deactivated by another (e.g., ROS) [31].

- NIR-II Excitation Source: 1064 nm laser [31].

- Spectrometer with InGaAs Detector: For measuring the absorption shift and NIR-II emission turn-on/off.

- Orthotopic Liver Tumor Model: Animal model for validating sensitive early cancer detection [31].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Probe Validation:

- Zero Initial Fluorescence: Confirm that the NDP probe has near-ideal zero fluorescence upon 1064 nm excitation in a buffer solution.

- Turn-On Response: Incubate the probe with the target biomarker (e.g., Hâ‚‚S). Use spectroscopy to verify a large absorption redshift (e.g., to 1066 nm) and the turn-on of NIR-II fluorescence (e.g., emission at 1138 nm).

- Turn-Off Response: Further incubate the activated probe with the deactivating agent (e.g., ROS). Confirm the fluorescence is quenched, returning to the "off" state.

- In Vivo Imaging:

- Inject the NDP probe into animal models bearing the target disease (e.g., orthotopic liver tumor) and healthy controls.

- Acquire NIR-II fluorescence images over time using 1064 nm excitation.

- Observe fluorescence turning on specifically in the disease tissue and turning off as the probe migrates to normal tissues, resulting in exceptionally low background.

Table 1: Comparison of Near-Infrared Bioimaging Windows

| Parameter | NIR-I Window | NIR-II Window | NIR-IIb/IIx Sub-Window |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Range | 700–900 nm [29] | 1000–1700 nm [30] [28] | 1500–1700 nm (IIb) [28] / 1400–1500 nm (IIx) [28] |

| Tissue Penetration Depth | ~0.2 mm (in brain tissue) [27] | Up to 3–4 mm [27] [28] | Deeper than broad NIR-II [28] |

| Spatial Resolution | Lower due to higher scattering | Superior, higher resolution [30] [29] | Highest (e.g., FWHM declines with μa) [28] |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) | Moderate, affected by autofluorescence | 2–4 fold higher than NIR-I for tumors [29] | Vastly improved contrast [28] |

| Tissue Autofluorescence | Noticeable | Minimal/negligible [27] [29] | Very low [28] |

| Key Fluorophore Examples | ICG, IRDye800CW [29] | CH1055-PEG, AIE Dots, Quantum Dots [30] [29] | PbS/CdS QDs (emitting at ~1450 nm) [28] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Different NIR-II Fluorescent Probes

| Probe Type | Example | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Excretion / Biocompatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Small Molecules | CH1055-PEG [29] | High renal excretion (>90%), tunable optical properties [29] | Relatively low quantum yield (e.g., 0.03%) [29] | Favorable (renal) [29] |

| Inorganic Nanomaterials | Quantum Dots, Rare-Earth Nanoparticles [30] [27] | High brightness, high photostability, multifunctionality [30] [27] | Poor biodegradability, potential long-term toxicity, liver/spleen accumulation [30] [27] | Unfavorable (hepatic, slow) [30] [27] |

| Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE) Dots | AIE Luminogen Dots [32] | High brightness, high photostability, good photothermal conversion efficiency (e.g., 40%) [32] | Complex synthesis, need for surface modification [30] | Can be engineered for improved biocompatibility [32] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for NIR Fluorescence Imaging Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | FDA-approved NIR-I dye for clinical angiography; can be used for its NIR-II emission tail [29]. | Absorption: ~805 nm; Emission: ~830 nm (peak) with a long tail to >1500 nm [29]. |

| Donor-Acceptor-Donor (D-A-D) Dyes | Organic NIR-II small molecule fluorophores (e.g., CH1055) [29]. | Systematic molecular tuning, emission at 900-1600 nm, potential for high renal excretion [29]. |

| PbS/CdS Core-Shell Quantum Dots (CSQDs) | Bright, wavelength-tunable inorganic probes for high-performance NIR-II imaging [28]. | Size-tunable emission (e.g., 1100–1450 nm), high quantum yield, PEG coating for hydration [28]. |

| AIE Luminogen (AIEgen) Dots | Nanoparticles for NIR-II imaging and photothermal therapy [32]. | High brightness in aggregated state, high photostability, high photothermal conversion efficiency [32]. |

| "Off-On-Off" Probes (e.g., NDP) | Activatable molecular probes for ultra-sensitive imaging with minimal background [31]. | Near-ideal zero initial fluorescence, ultra-high turn-on/off ratio, biomarker-responsive (e.g., Hâ‚‚S) [31]. |

| InGaAs Camera | Essential detector for NIR-II and SWIR light. | Sensitive in the 900-1700 nm range (standard) or beyond (up to 2500 nm for advanced systems) [28]. |

| 16,17-EDT | 16,17-EDT, MF:C22H36O3, MW:348.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Carmichaenine A | Carmichaenine A, MF:C31H43NO7, MW:541.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Common NIR-II Experimental Challenges

This guide addresses specific technical issues you might encounter during NIR-II fluorescence imaging experiments, providing targeted solutions to ensure data quality and experimental success.

FAQ 1: My NIR-II fluorescence signal is unexpectedly weak. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A weak signal can stem from the fluorophore itself or the imaging setup. The table below outlines common causes and corrective actions.

| Primary Cause | Root Issue | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Fluorophore Quantum Yield | Innately low radiative transition efficiency in NIR-II window [10]. | Select fluorophores with S-D-A-D-S molecular design or AIEgens to reduce aggregation-caused quenching [33] [34]. |

| Environmental Quenching | Interaction with water molecules increases non-radiative decay [33]. | Encapsulate organic dyes in nanoparticles or serum albumin to shield from aqueous environment [10]. |

| Insufficient Excitation Power | Power density is too low to generate sufficient fluorescence. | Increase laser power within safe limits for living tissue (typically <100 mW/cm² for in vivo studies). |

| Suboptimal Imaging Setup | Use of inappropriate filters or detector inefficiency. | Confirm long-pass emission filter cutoff and ensure InGaAs detector is optimized for 1000-1700 nm range [35] [36]. |

FAQ 2: How can I differentiate between specific and non-specific fluorescence signals in deep tissue?

Non-specific signals can be addressed through probe design and advanced imaging techniques.

| Challenge | Solution | Experimental Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal | Use brighter probes and target-specific ligands. | Conjugate targeting moieties (e.g., peptides, antibodies) to fluorophores; employ conjugated polymers for higher brightness [33] [37]. |

| Unclear Signal Origin | Leverage lifetime imaging. | Use time-gated detection or TCSPC to measure luminescence lifetime, which is concentration-independent and discriminates against autofluorescence [38]. |

FAQ 3: My NIR-II probe shows poor biocompatibility or cellular toxicity. How can this be mitigated?

Biocompatibility is closely tied to a probe's physicochemical properties and clearance pathway.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Toxicity | Cytotoxicity from probe materials (e.g., heavy metals in QDs). | Prioritize organic small molecules or rare-earth nanoparticles with low toxicity profiles [33] [39]. |

| Chronic Toxicity / Long-term Retention | Slow bodily clearance, leading to organ accumulation. | Design small hydrodynamic diameter (<6 nm) probes for rapid renal clearance [39]. Apply hydrophilic PEG coatings to reduce MPS uptake [39]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rationally Designing an Organic Small Molecule NIR-II Fluorophore

This protocol outlines the synthesis of high-performance organic NIR-II fluorophores based on established molecular engineering principles [33] [10] [34].

Key Reagents:

- Donor (D) Units: Strong electron-donating groups (e.g., triphenylamine, phenothiazine).

- Acceptor (A) Units: Strong electron-accepting groups (e.g., benzobisthiadiazole, thienothiadiazole).

- Shielding (S) Units: Bulky, twisted groups (e.g., bulky alkyl chains, xylyl) to reduce intermolecular interactions.

Methodology:

- Scaffold Selection: Construct a D-A-D or S-D-A-D-S molecular backbone. The S-D-A-D-S structure is superior for suppressing fluorescence quenching in aqueous environments [33].

- Energy Level Tuning: Adjust the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) strength by modifying the electron-donating/accepting capabilities of D and A units. A stronger ICT leads to a longer emission wavelength [10].

- Aggregation Control: For NIR-II Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogens (AIEgens), introduce molecular rotors/vibrons into a D–A–D–A–D–A–D scaffold. This creates an AIE–ACQ–AIE architecture that balances brightness and redshift [34].

- Water Solubilization: Covalently link hydrophilic polymers (e.g., PEG) or sulfonate groups to the conjugated skeleton to ensure biocompatibility and facilitate renal clearance [39].

Protocol 2: Conducting a High-Contrast In Vivo NIR-II Angiography

This procedure details the steps for visualizing blood vessels with high spatial resolution in live animals [35] [36].

Key Reagents:

- NIR-II Fluorophore: IR-1048 dye, Ag2S Quantum Dots, or organic dye-loaded nanoparticles (e.g., MTBTMT-BBT NPs [34]).

- Anesthesia: Isoflurane or ketamine/xylazine mixture.

- Physiological Saline: For probe dilution and injection.

Methodology:

- Probe Preparation: Dilute the NIR-II fluorophore in sterile physiological saline to a working concentration (e.g., 100-500 µM). Filter the solution through a 0.22 µm membrane.

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize the animal and secure it on a heated imaging stage to maintain body temperature. Remove hair from the imaging area as needed.

- System Setup: Use a preclinical NIR-II imaging system (e.g., IR VIVO) with an InGaAs camera. Set excitation laser to 808 nm or 1064 nm and place a long-pass emission filter (e.g., LP1250 or LP1500) appropriate for the probe's emission [35].

- Image Acquisition:

- Acquate a baseline image before injection.

- Intravenously inject the probe solution via the tail vein.

- Start continuous image acquisition immediately post-injection. Use short exposure times (e.g., 20-100 ms) to capture dynamic blood flow.

- Data Analysis: Use region-of-interest (ROI) analysis to calculate signal-to-background ratios (SBR) and generate time-intensity curves for hemodynamic analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential materials used in advanced NIR-II experiments, along with their critical functions.

| Research Reagent | Category | Primary Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CH1055-PEG | Organic Small Molecule | First reported D-A-D structured NIR-II dye; used for tumor-targeted molecular imaging when conjugated to antibodies (e.g., anti-EGFR) [33]. |

| IR-BEMC6P@RGD | Targeted Organic Probe | S-D-A-D-S structured probe with high quantum yield; RGD peptide conjugation enables specific imaging of integrin-positive tumors [33]. |

| Ag2S Quantum Dots (QDs) | Inorganic Nanoparticle | Low-toxicity inorganic option; used in dual-modal probes (e.g., Gd-DOTA-Ag2S QDs) for MRI and NIR-II image-guided surgery [37]. |

| CC-LnNPs | Biomimetic Nanoprobes | Lanthanide-doped nanoparticles coated with a brain tumour cell membrane; enables immune escape and homologous targeting for precise glioma imaging and resection [37]. |

| MTBTMT-BBT NPs | AIEgen Nanoparticles | Multidimensional engineered fluorophore for dual NIR-II imaging and photothermal therapy (57.9% PCE); excitable at 808, 980, and 1064 nm [34]. |

| ICG (Indocyanine Green) | Clinical NIR-I/II Dye | FDA-approved dye with a fluorescence tail in NIR-II; serves as a benchmark; modified versions (e.g., 64Cu DOTA-FA-ICG) used for NIR-II guided surgery [37] [35]. |

| Dazdotuftide | Dazdotuftide | TRS01 Immunomodulator Research Compound | |

| Anticancer agent 58 | Anticancer agent 58, MF:C39H55NO5, MW:617.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary factors that limit penetration depth in fluorescence imaging, and how can probe selection help overcome them? The primary factors are tissue absorption and scattering of light. Different tissue components, or chromophores, absorb light, while scattering occurs when light changes direction after bouncing off tissue structures [18]. Selecting probes that emit in the Near-Infrared (NIR) windows, particularly NIR-II (1000-1700 nm) and NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm), is a key strategy. In these windows, light experiences significantly less absorption and scattering from biological tissues, enabling deeper penetration and higher-resolution imaging [18] [40].

Q2: My fluorescent signal is too weak for detection through tissue. What should I check? First, verify the fundamental properties of your probe and system:

- Emission Wavelength: Ensure your probe emits in the NIR-I or NIR-II region. Visible light probes (e.g., blue, green) are heavily attenuated by tissue [18].

- Probe Brightness: Check the quantum yield (QY) of your probe. A higher QY indicates a brighter probe. For example, some AIEgens are engineered to maintain a QY of over 11% even in the NIR-II region, which is exceptional for organic dyes [40].

- System Settings: Confirm that your imaging system's excitation source and camera are optimized for the excitation and emission wavelengths of your probe [18] [2].

Q3: I am using an organic dye, but its fluorescence is quenched when it aggregates in aqueous solution. How can I prevent this? This is a classic case of Aggregation-Caused Quenching (ACQ). Consider switching to probes based on Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogens (AIEgens). Unlike conventional dyes, AIEgens are non-emissive in solution but become highly fluorescent in their aggregated state due to the restriction of intramolecular motion, making them ideal for forming bright nanoparticles for bioimaging [40].

Q4: I am getting high background noise during in vivo imaging. What could be the cause? High background is often due to tissue autofluorescence, where native tissue components emit light, typically in the blue-green spectrum [2] [41]. To minimize this:

- Use NIR-II Probes: Autofluorescence is significantly reduced in the NIR-II window, leading to a much higher signal-to-background ratio [40].

- Employ Quenchers: Use commercial autofluorescence quenchers if you are stuck working in the visible spectrum [2].

- Check Probe Specificity: Ensure your probe is effectively targeting the area of interest and not binding non-specifically [41].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No or Weak Signal | Probe emission wavelength is in the visible spectrum. | Switch to a NIR-emitting probe (e.g., NIR-II AIEgen or cyanine dye) [18] [40]. |

| The probe's quantum yield is too low for deep-tissue detection. | Use a brighter probe with a higher QY (e.g., Carbon Quantum Dots or high-QY AIEgens) [42] [40]. | |

| Probe concentration is too low. | Perform a titration experiment to determine the optimal concentration for your application [2]. | |

| High Background Noise | Tissue autofluorescence. | Image in the NIR-IIb (1500-1700 nm) window where autofluorescence is nearly zero [40]. |

| Non-specific binding of the probe. | Functionalize the probe with targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) for specific accumulation [41]. | |

| Signal Quenching in Water | Aggregation-Caused Quenching (ACQ) of conventional organic dyes. | Use probes with inherent AIE properties that turn on upon aggregation [40]. |

| Poor Photostability | Fluorophore is being degraded by the excitation light (photobleaching). | Use mounting media with antifade reagents or choose more photostable dyes (e.g., rhodamine-based dyes or Carbon Dots) [2] [42]. |

| Inability to Resolve Deep Targets | Excessive light scattering at the imaging wavelength. | Utilize probes with longer emission wavelengths (e.g., NIR-II/J-aggregate BODIPY) to reduce scattering [21] [43]. |

Quantitative Data and Probe Performance

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for various next-generation fluorescence probes, which are critical for selecting the right agent to overcome penetration depth limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Next-Generation Fluorescence Imaging Probes

| Probe Category | Examples | Typical Emission Range | Key Advantages | Documented Penetration Depth / Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Dyes (Cyanines) | ICG, Cy7 [44] | NIR-I (∼800 nm) | FDA-approved (ICG), high absorption coefficients [44]. | Widely used for clinical imaging and angiography. |

| BODIPY Dyes | PCP-BDP2 J-aggregates [43] | NIR-II (1010 nm) | Tunable structure, high stability; J-aggregates enable NIR-II emission [43]. | Lymph node imaging and guided surgery in mice [43]. |

| AIEgens | 2TT-oC26B nanoparticles [40] | NIR-II up to 1600 nm | Bright in aggregate state (AIE), high QY (11.5%), low background [40]. | High-resolution imaging of blood vessels and deeply-located intestinal tract in live mice [40]. |

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials | Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) [45] [42] | Tunable, visible to NIR | Biocompatibility, low toxicity, ease of functionalization [45] [42]. | Used for bioimaging, drug delivery, and phototherapy [42]. |

| Inorganic Nanomaterials | Quantum Dots, Rare-Earth Nanoparticles [40] | NIR-II & NIR-IIb | High brightness, photostability [40]. | Deep-tissue and tumor imaging with high resolution [40]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterizing Imaging System Depth Sensitivity Using Tissue-Mimicking Phantoms

This protocol is essential for quantitatively evaluating the performance of any fluorescence imaging system and probe combination for deep-tissue applications [18].

Materials Needed:

- Fluorescence imaging system

- Tissue-mimicking depth sensitivity reference target (e.g., phantom with wells of varying depths above a fluorescent layer)

- Standardized fluorescent solution (e.g., ICG)

Methodology:

- Image Acquisition: Using your fluorescence imaging system, capture an image of the depth target under standard clinical conditions (e.g., typical working distance, ambient lighting, and system settings) [18].

- Intensity Measurement: For each well in the phantom, measure the mean pixel intensity within a region of interest (ROI) that covers about half the diameter of the well. This can be automated with analysis software [18].

- Data Analysis & Plotting: Plot the measured mean pixel intensity (or the Contrast-to-Noise Ratio, CNR) against the known tissue-equivalent depth of each well [18].

- Fit and Interpret: Fit the data to an exponential decay equation. The depth at which the CNR drops below a threshold (commonly 3) is considered the system's limit of detection for that specific probe and tissue type [18].

This advanced protocol allows for depth estimation of fluorescent targets in turbid media [21].

Materials Needed:

- sCMOS camera with a liquid crystal tunable filter (LCTF)

- Broadband white light source (e.g., tungsten halogen lamp) for reflectance.

- Diode laser for fluorescence excitation (e.g., 635 nm for AF647 dye).

- Tissue-simulating phantoms with embedded fluorescent inclusions.

Methodology:

- Dual-Modality Image Acquisition:

- Calculate Dual-Wavelength Fluorescence Ratio (DWFR): For each pixel, calculate the ratio of fluorescence intensities at two carefully selected wavelengths (e.g., 670 nm and 700 nm) [21].

- Depth Estimation: Use a pre-calibrated linear relationship between the DWFR and the fluorophore depth to convert the ratio values into a depth map. This technique can resolve fluorescent sources up to 6 mm deep, even when multiple sources are present [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Deep-Tissue Fluorescence Imaging Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Tissue-Mimicking Phantoms | Contains materials with well-characterized absorption (μa) and reduced scattering (μs') coefficients to simulate human tissue for standardized system testing and validation [18] [21]. |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | An FDA-approved NIR-I cyanine dye used as a clinical benchmark and for validating new imaging systems and surgical guidance protocols [44]. |

| NIR-II AIEgen Nanoparticles | Organic nanoparticles (e.g., based on 2TT-oC26B) that provide bright, red-shifted emission for high-resolution, deep-tissue imaging with minimal background [40]. |

| J-Aggregating BODIPY Dyes | BODIPY dyes (e.g., PCP-BDP2) engineered to form J-aggregates, which shift emission into the NIR-II window for applications like lymph node mapping [43]. |

| Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) | Biocompatible, low-toxicity nanoprobes used for bioimaging, sensing, and drug delivery, often with tunable emission wavelengths [45] [42]. |

| TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher | A commercial reagent used to suppress tissue autofluorescence, a major source of background noise, particularly in the visible light spectrum [2]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Molecular Design Logic for NIR-IIb AIEgens

Diagram: Workflow for Depth Sensitivity Characterization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

General Questions on FDA-Approved Fluorescent Probes

Q1: What are the key FDA-approved fluorescent agents for clinical imaging? Currently, the primary FDA-approved fluorescent agents for clinical imaging are Indocyanine Green (ICG), Methylene Blue (MB), and 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (5-ALA) [46] [47].

Q2: What are the main advantages of optical imaging over other modalities like PET? Optical imaging is non-invasive and does not involve ionizing radiation, making it safer for patients. It also offers the potential for real-time imaging and provides high molecular sensitivity, which can assist in clinical decision-making [46].

Q3: Why is penetration depth a significant limitation in fluorescence imaging? Biological tissues scatter and absorb light. Components like hemoglobin, water, and lipids absorb photons, which reduces the light that can penetrate deeply and return to the detector, thus limiting effective imaging depth [46] [10].

Technical and Experimental Troubleshooting

Q1: The fluorescence signal in my clinical image is weak or has poor contrast. What could be the cause? This is a common challenge in clinical translation. Potential causes and solutions include [46] [2] [48]:

- Cause: The fluorophore's emission wavelength is in the visible spectrum, where tissue autofluorescence and light absorption are high.

- Solution: Utilize fluorophores that emit in the Near-Infrared (NIR) windows (e.g., NIR-I: 700-900 nm; NIR-II: 1000-1700 nm) where tissue autofluorescence is minimal, and penetration is deeper [46] [10]. ICG, which emits around 820-840 nm, is a prime example [46].

- Cause: Photobleaching of the fluorophore during imaging.

- Solution: Ensure your imaging device uses appropriate light intensity and exposure times. Using highly photostable fluorescent scaffolds (e.g., BODIPYs) can also help, though these are largely still in preclinical stages [46] [14].

- Cause: High background signal from non-specific binding or tissue autofluorescence.

- Solution: For tissue samples, include an unstained control to gauge autofluorescence levels. Using autofluorescence quenchers can also improve the signal-to-background ratio [2].

Q2: Why do only a few targeted fluorescent probes achieve clinical translation? The translation of molecular optical agents to the clinic is challenging due to three interconnected areas [46]:

- Fluorophore Development: It is difficult to develop molecular fluorophores with long-wavelength emission, high brightness, and limited photobleaching. Most clinical imaging devices are designed for the wavelengths of ICG [46].

- Biological Target Selection: The target must be selectively associated with the disease and expressed at a high enough level to generate sufficient contrast. Common targets are cancer-associated surface receptors and enzymes [46].

- Hardware and Software: Clinical imaging devices must be sensitive, compatible with NIR wavelengths, and have ergonomic designs for use in operating rooms or clinics [46].

Q3: How can I improve the specificity of a fluorescent probe for my target? Nonspecific agents like ICG rely on the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect for accumulation in tumors. To increase specificity, research focuses on ligand-based targeting strategies. This involves conjugating fluorophores to targeting moieties like peptides (e.g., EMI-137 targeting c-MET), antibodies (e.g., cetuximab-IRDye800CW), or vitamins (e.g., OTL38 targeting the folate receptor) [46] [47].

Comparison of Key FDA-Approved Fluorescent Probes

The table below summarizes the critical characteristics of the main FDA-approved fluorescent imaging agents [46] [47] [49].

Table 1: Summary of FDA-Approved Fluorescent Probes for Clinical Imaging

| Imaging Agent | Excitation/Emission (nm) | Primary Mechanism | Key Clinical Applications | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | Exc: ~780 nmEm: ~820 nm [46] | Nonspecific; accumulates via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect; based on blood supply and lymphatic drainage [46] [49]. | Sentinel lymph node mapping [46]; evaluation of tissue perfusion (e.g., gastric conduit after esophagectomy) [49]; imaging of bullous lesions and the thoracic duct [49]. | Nonspecific; insufficient for high signal-to-background ratios in some tumors [46]. |

| 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (5-ALA) | Exc: 405 nmEm: 635 nm (as PpIX) [47] | Metabolic precursor to fluorescent Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX); accumulates in glioma cells due to reduced ferrochelatase activity [47]. | Visualization and resection of high-grade gliomas (WHO Grade III/IV) [47]. | Limited to surfaces due to visible light emission; less effective in low-grade gliomas [47]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | Exc: ~665 nmEm: ~685 nm [46] | Nonspecific; can accumulate in certain tumor types. | Identification of small intestine neuroendocrine tumors (SI-NETs) [46]. | Emission in visible spectrum limits penetration depth and contrast [46]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Intraoperative Fluorescence-Guided Tumor Resection using 5-ALA

This protocol is standard for the resection of high-grade gliomas [47].

- Objective: To achieve real-time visualization and improved resection of malignant glioma tissue.

- Materials:

- 5-ALA hydrochloride (commercially available formulation)

- A neurosurgical microscope equipped with a blue light source (~405 nm) and appropriate filters for detecting red fluorescence (~635 nm)

- Procedure:

- Administration: Approximately 3 hours before induction of anesthesia, administer 20 mg per kg of body weight of 5-ALA orally to the patient [47].

- Metabolic Conversion: Endogenous enzymes in the tumor cells convert 5-ALA into the fluorescent compound Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). Due to reduced levels of the enzyme ferrochelatase in glioma cells, PpIX accumulates and cannot be efficiently converted to non-fluorescent haem [47].