Strategies for Enhancing Signal-to-Background Ratio in Deep Tissue Imaging: From Optical Hardware to Computational AI

This article synthesizes the latest advancements for improving the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) in deep tissue imaging, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategies for Enhancing Signal-to-Background Ratio in Deep Tissue Imaging: From Optical Hardware to Computational AI

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advancements for improving the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) in deep tissue imaging, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore foundational principles, including the benefits of long-wavelength illumination in the 1700 nm spectral band and the superior background suppression of three-photon microscopy. The review covers cutting-edge methodological approaches, from novel optical systems and super-resolution upgrades to the integration of deep learning with custom nanoprobes. We also provide a practical guide for troubleshooting common SBR limitations and present a comparative analysis of technique validation, empowering scientists to select and optimize the right tools for visualizing subcellular structures and neural activity at unprecedented depths in living brains.

Understanding the Core Challenge: Why Scattering and Background Limit Deep Tissue Imaging

In deep tissue imaging, light propagation is fundamentally limited by the interaction of photons with biological matter. As light travels through tissue, its intensity is attenuated primarily through two physical processes: scattering and absorption [1].

- Scattering occurs when light particles (photons) collide with and bounce off tiny structures and particles within the tissue. This randomizes the direction of light, blurring images and reducing the signal that can be detected from a specific focal point. The scattering mean free path is the average distance a photon travels between scattering events; in biological tissues, this is typically on the order of a few hundred microns [1].

- Absorption happens when photons transfer their energy to molecules in the tissue, such as hemoglobin, pigments, and water. This energy transfer prevents the light from propagating further, directly diminishing the signal intensity [1].

The combined effect of these phenomena results in a rapid exponential decay of usable signal with imaging depth. The signal from ballistic photons decreases to just 13.5% at a depth of one scattering mean free path [1]. This severe attenuation is the primary physical barrier that deep tissue imaging techniques strive to overcome.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my image signal become unusable so quickly when I try to image deeper than 200-300 microns?

This is a classic symptom of signal attenuation due to scattering and absorption. The exponential decay of signal strength with depth follows the relationship described in the introduction. To confirm this is the issue, try the following troubleshooting steps:

- Diagnose: Image a thin, well-characterized control sample. If the signal is strong at the surface but degrades rapidly with depth, attenuation is the likely cause.

- Verify: Check if your system allows for manual power adjustment. Gradually increase laser power as you focus deeper into the sample. If the signal improves significantly at greater depths with higher power, it confirms that attenuation is your core problem [2].

FAQ 2: My images from deep within a sample have a very low signal-to-background ratio (SBR). What can I do to improve this?

A low SBR indicates that the desired signal is being overwhelmed by background noise, often from scattered photons or autofluorescence.

- Solution A: Optimize Your Optical Path: Reduce excess background noise by ensuring all filters are clean and correctly positioned. Consider adding secondary emission and excitation filters to block stray light more effectively [3].

- Solution B: Leverage Advanced Imaging Probes: Switch to imaging probes that operate in the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm). In this spectral region, tissue scattering and absorption are significantly lower, leading to deeper penetration and higher SBR [1].

- Solution C: Implement Power Compensation: For laser-scanning microscopes, create a power compensation curve. Manually or automatically increase the laser power as you image deeper into the sample to maintain a consistent signal level and counteract absorption [2].

FAQ 3: I am using fluorescent proteins, but their signal is lost during my tissue clearing protocol. What went wrong?

This is a common pitfall where the solution to one problem (scattering) inadvertently creates another (signal loss).

- Diagnosis: The chemical environment created by the clearing protocol is likely quenching the fluorescence or damaging the fluorophores.

- Troubleshooting: This requires an iterative optimization process. You must find a clearing protocol that balances transparency with signal preservation. As documented in one case study, a switch from a hydrogel-based protocol (CLARITY) to an organic solvent method (ethyl cinnamate) successfully preserved signal, though it introduced new challenges like chromatic aberration that also needed correction [4].

Quantitative Data and Specifications

Table 1: Comparison of Optical Imaging Windows for Deep Tissue

| Imaging Window | Wavelength Range | Primary Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible Light | ~400 - 650 nm | High resolution for surface imaging; wide range of available dyes. | Very poor penetration depth; high scattering and absorption. |

| NIR-I | 650 - 900 nm | Reduced scattering vs. visible light; FDA-approved dyes (e.g., ICG). | Penetration depth often <1 mm. |

| NIR-II | 1000 - 1700 nm | Deeper penetration; reduced scattering/absorption; high SBR; low autofluorescence. | Lack of bright, nontoxic, and versatile fluorophores. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Signal Penetration

| Reagent Type | Function & Mechanism | Example Materials | In Vivo Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorophores | Emit light in the NIR-II window for deeper penetration and reduced scattering. | Semiconducting polymer nanoparticles, quantum dots (QDs), heptamethine-cyanine-based fluorophores. | Tracking mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) subcutaneously injected in mice [1]. |

| Bioluminescence Probes | Generate light via chemical reaction, eliminating need for excitation light and its associated scattering/background. | Nano-luciferase complexes, fusion proteins with coelenterazine substrates. | Tumor imaging in mice via intravenous injection of nanocage-luciferin conjugates [1]. |

| Afterglow Probes | Emit light after the excitation light is off, dramatically increasing SBR by removing background from excitation. | ZnSn2O4:Cr,Eu nanoparticles, semiconducting polymer nanoparticles. | Lymph node and tumor imaging in mice after intravenous injection [1]. |

| DNA-Templated Nanoclusters | AI-designed contrast agents tuned for the NIR-II window; offer potential for brightness and biocompatibility. | DNA-templated silver or gold nanoclusters. | Under development for cancer research and image-guided surgery [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Manual Power Compensation for Deep Z-Stacks

This protocol allows you to empirically determine the necessary laser power to maintain a consistent signal at different depths within a scattering sample [2].

- Setup: Mount your stained sample and select a representative field of view.

- Initial Measurement: Focus at the most superficial plane (e.g., 5 µm deep). Adjust the laser power and detector gain to achieve a bright signal without saturation. Note the laser power percentage and the average pixel intensity in your region of interest (ROI).

- Depth Series: Move the focal plane to a deeper position (e.g., 30 µm). Observe the signal intensity in your ROI. It will have decreased.

- Power Adjustment: Increase the laser power until the average pixel intensity in the ROI matches the value you recorded at the superficial plane. Record the new laser power and depth.

- Repeat: Continue this process for multiple depths throughout the range you wish to image (e.g., 5, 20, 40, 60, 80 µm), creating a table of depth vs. laser power.

- Application: When acquiring your final z-stack, manually input the recorded laser power at each corresponding depth. Caution: When returning to shallower depths, remember to reduce the laser power to avoid photodamage and photobleaching.

Protocol 2: Implementing Lightsheet Line-Scanning SIM (LiL-SIM) for Super-Resolution in Deep Tissue

This advanced protocol modifies a two-photon laser-scanning microscope to achieve super-resolution imaging deep within scattering tissues [6].

System Modification:

- Hardware Addition: Integrate a cylindrical lens, a Dove prism (mounted on a rotation stage with a half-wave plate) acting as a field rotator, and a sCMOS camera with a lightsheet shutter (LSS) mode into the microscope's detection path.

- Synchronization: Ensure precise synchronization between the laser scanning, the rotation of the Dove prism, and the rolling shutter of the sCMOS camera.

Image Acquisition:

- Pattern Generation: Instead of full-frame illumination, a single line focus is scanned across the sample to build up a striped illumination pattern.

- Field Rotation: For each super-resolution frame, the Dove prism is rotated to three distinct angles (e.g., 0°, 30°, and 60° to achieve 0°, 60°, and 120° field rotations).

- LSS Mode: The camera's rolling shutter is activated as a thin, sliding band that precisely follows the illuminating line focus. This blocks a significant portion of scattered light from out-of-focus planes, dramatically improving the detected contrast.

- Two-Photon Excitation: Use a pulsed laser for two-photon excitation to inherently limit fluorescence to the focal volume, further improving image contrast in deep tissue.

Image Reconstruction:

- The raw image set is processed using structured illumination microscopy (SIM) reconstruction algorithms to generate the final super-resolution image with up to a twofold resolution enhancement.

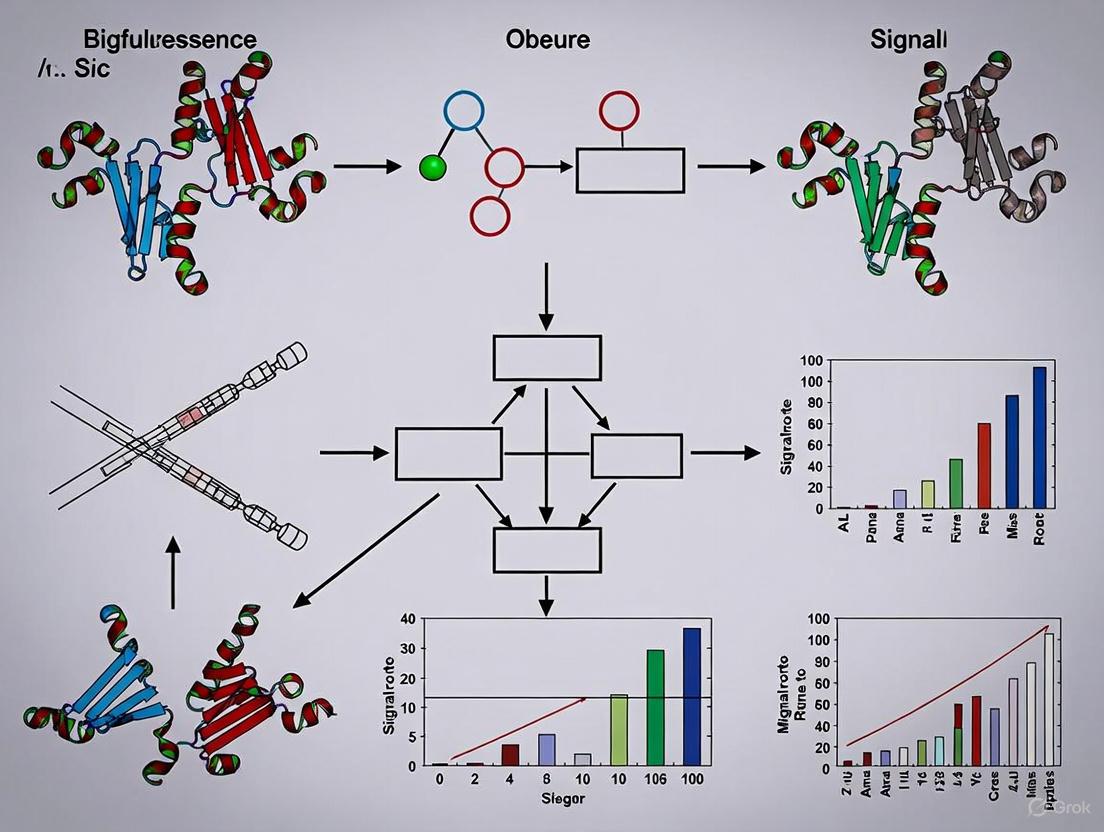

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental challenge of signal attenuation and the core strategies to mitigate it, as discussed in this guide.

Defining Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) as a Key Metric for Image Quality

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) and why is it critical for deep-tissue imaging? SBR is a quantitative measure that compares the intensity of a desired signal from a target (e.g., a labeled neuron or tumor) to the intensity of the background noise. A high SBR is crucial because it directly impacts image contrast and clarity. In deep-tissue imaging, light scattering and autofluorescence can severely degrade SBR, making it difficult to distinguish true biological signals from background interference. A low SBR can lead to inaccurate data interpretation and false positives [7] [8].

2. My images have high signal but still appear noisy and unclear. Is the problem SBR or Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)? This is a common point of confusion. While related, SBR and SNR measure different things.

- SBR concerns the contrast between your target's signal and the background fluorescence or scattered light from out-of-focus planes.

- SNR concerns the strength of your target's signal relative to random electronic or stochastic noise (e.g., from the camera detector) [8]. An image can have a high SNR (a strong, clear signal) but a low SBR if the background is also very bright, resulting in poor contrast. Techniques like optical sectioning (e.g., multiphoton microscopy) are specifically designed to improve SBR by suppressing out-of-focus background [7].

3. What are the primary factors that reduce SBR in deep-tissue experiments? Several factors contribute to SBR reduction:

- Light Scattering: Biological tissue scatters both excitation and emission light, blurring the focus and creating a diffuse background [9] [7].

- Out-of-Focus Light: In wide-field microscopy, the entire sample is illuminated, so fluorescence from above and below the focal plane contributes to background [10].

- Autofluorescence: Native molecules in tissue can fluoresce when excited, adding to the background signal [11].

- Absorption: Light absorption by tissue components (like water or hemoglobin) can attenuate your signal, especially at certain wavelengths [7].

4. How can I calculate SBR from my image data?

There is no single universally agreed-upon formula, which can affect performance assessment [8]. However, a common and practical method is:

SBR = (Mean Signal Intensity in Target ROI - Mean Background Intensity) / Mean Background Intensity

Select a Region of Interest (ROI) over your target and another ROI in a nearby, featureless background area. The variability in how the background ROI is selected can significantly influence the calculated SBR value, so consistency is key [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low SBR in Deep-Tissue Fluorescence Imaging

Symptoms: Faint target signal, hazy images with high background, poor contrast that makes structures difficult to distinguish.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Key Technique / Reagent |

|---|---|---|

| Intense out-of-focus background & scattered light | Implement structured illumination microscopy. This method uses a patterned light sheet to illuminate only the focal plane, dramatically rejecting background from other planes. | Robust Fourier Light Field Microscopy (RFLFM) [10]. |

| Scattering of excitation light | Use Bessel-beam illumination. Bessel beams are "self-healing" and can reconstruct their original structure after passing through scattering particles, improving imaging depth and contrast. | Bessel-Gauss (BG) Beam [9]. |

| Background from random noise & false detections | Apply correlation-based analysis in single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM). This identifies "fortunate molecules" that blink for multiple consecutive frames, rejecting random, one-frame noise events. | corrSMLM technique [12]. |

| Poor penetration of excitation light | Utilize near-infrared-excitable afterglow nanoparticles. These probes are excited by deep-penetrating NIR light and emit persistent luminescence after excitation ceases, eliminating autofluorescence background. | Near-Infrared-Excitable Organic Afterglow Nanoparticles (NOANPs) [11]. |

| Trade-off between penetration and resolution | Employ deep learning-enhanced dual-modal fluorescence imaging. This uses lanthanide nanoparticles that emit two different fluorescence wavelengths simultaneously, fusing deep-penetration data with high-resolution data via a neural network. | Deep Learning Enhanced Dual-Modal Fluorescence Cooperative Imaging (DL-DMFC) with Upconversion Nanoparticles (UCNPs) [13]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Wavefront Shaping with a Bessel-Gauss Beam to Enhance SBR

This protocol is adapted from recent research that combines wavefront shaping with specialized beams to counteract scattering [9].

Objective: To optimize the incident wavefront using a scoring-based genetic algorithm (SBGA) to enhance the fluorescence signal and SBR of multiple hidden targets behind a scattering medium.

Materials and Reagents:

- Laser Source: Continuous-wave helium-neon laser (632.8 nm) or similar.

- Spatial Light Modulator (SLM): Phase-only SLM (e.g., Santec SLM-200).

- Microscopy Setup: Home-built optical microscope with two microscope objectives (e.g., 10x/0.3 NA and 20x/0.4 NA).

- Beam Shaping Optics: Axicon (α=0.5°) to convert a Gaussian beam into a Bessel-Gauss (BG) beam.

- Fluorescent Sample: Carboxylate-modified polystyrene fluorescent microspheres (40 nm diameter).

- Scattering Samples: Pig skin tissue, ground-glass diffusers, or parafilm.

- Detection: Scientific camera (e.g., Thorlabs CS2100M) with appropriate emission filter.

- Software: MATLAB (or equivalent) for controlling the SLM, camera, and running the SBGA.

Procedure:

- Setup Configuration: Expand and collimate the laser beam. Place the axicon in the beam path to form a BG beam after the first microscope objective (MO1). The SLM should be positioned to modulate the phase of this BG beam.

- Sample Preparation: Randomly disperse fluorescent microspheres on a microscope slide. Place this slide behind your chosen scattering layer (e.g., a 1.5 mm-thick ground-glass diffuser).

- Initial Image Acquisition: Display a random initial phase mask on the SLM. Use the camera to record the resulting fluorescence image (

S1). - Image Thresholding: Apply a threshold to this initial image to separate potential target pixels from background noise. Calculate the threshold

τasτ = w_max × t_c, wherew_maxis the maximum intensity level in the image andt_c(a correction factor between 0 and 0.5) is inversely related to the initial SNR. - Create Thresholded Image: Generate a thresholded image

Gwhere all pixels with intensity belowτare set to zero. - Calculate Objective Functions: For the thresholded image

G, compute two image quality metrics:- Image Entropy (H):

H = -Σ [P(w_i) * log2(P(w_i))], whereP(w_i)is the probability of intensity levelw_i. This maximizes information and detail. - Average Intensity (I):

I = (1/(m*n)) * ΣΣ g(x,y), which maximizes the signal strength.

- Image Entropy (H):

- Run Scoring-Based Genetic Algorithm (SBGA):

- Generate & Score: Create a population (e.g., 100) of random phase masks. For each, capture an image, create its thresholded version, and calculate its scores (

s_Hands_I) based on its H and I values. - Rank & Select: Rank all phase masks by their combined score (

s_H + s_I). Select the top-performing masks as "parents." - Breed & Mutate: Create a new "generation" of phase masks by combining traits from parents and introducing small random mutations (phase changes).

- Iterate: Repeat the process of scoring, ranking, and breeding for multiple generations (e.g., 50-200) until the combined score converges to a maximum.

- Generate & Score: Create a population (e.g., 100) of random phase masks. For each, capture an image, create its thresholded version, and calculate its scores (

- Apply Optimal Wavefront: The phase mask with the highest combined score at the end of the SBGA is the optimal wavefront (

u_opt). Display this mask on the SLM to acquire the final, enhanced fluorescence image with significantly improved SBR.

Problem: Inconsistent SBR Measurements Across Different Imaging Sessions

Symptoms: SBR values for the same sample and setup vary from day to day, making it difficult to compare results quantitatively.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inconsistent background region selection | Standardize the process for selecting the background ROI. Always use the same relative location and size for the background ROI (e.g., an adjacent area of the same size and shape as the target ROI). Document this protocol for all users. [8] |

| Variation in laser power or detector sensitivity | Implement a daily quality control procedure. Image a standardized reference phantom with known fluorescent properties and ensure the measured signal and background values fall within an accepted range before beginning experiments. [8] |

| Changes in ambient light or sample preparation | Ensure imaging is performed in complete darkness to eliminate ambient light. Strictly adhere to a documented and consistent sample preparation protocol to minimize variability in labeling concentration and sample mounting. [8] |

Research Reagent Solutions for SBR Enhancement

The following table details key reagents and materials used in advanced methods for improving SBR.

| Reagent / Material | Function in SBR Enhancement | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Near-Infrared-Excitable Organic Afterglow Nanoparticles (NOANPs) | Eliminates real-time excitation light and tissue autofluorescence by emitting persistent luminescence after NIR excitation has ceased. This results in an exceptionally high SBR. | Deep-tissue imaging of orthotopic pancreatic cancer and glioma models in mice [11]. |

| Upconversion Nanoparticles (UCNPs) | Allows for dual-modal imaging under a single NIR excitation wavelength. Provides both a deep-penetrating emission (e.g., 808 nm) and a high-resolution emission (e.g., 455 nm), enabling computational fusion for deep, high-SBR images. | Deep learning-enhanced cooperative imaging beyond 500 μm depth, overcoming the penetration-resolution trade-off [13]. |

| Bessel-Gauss (BG) Beam | A specialized light beam that is "non-diffracting" and possesses "self-healing" properties. It can reconstruct after encountering small obstacles, reducing scattering-induced distortion and maintaining a tight focus for better SBR at depth. | Wavefront shaping experiments to image fluorescent targets through scattering media like pig skin tissue [9]. |

| Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) | A device that actively controls and shapes the wavefront of light. It is used to apply corrective phase patterns that can pre-compensate for scattering in tissue, effectively refocusing light onto the target to boost signal. | Core component in wavefront shaping setups for correcting aberrations [9]. |

Quantitative SBR Improvement Data from Recent Studies

The table below summarizes the SBR enhancements achieved by various techniques as reported in the literature.

| Technique / Method | Reported SBR Improvement | Key Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Robust Fourier Light Field Microscopy (RFLFM) | Improved by orders of magnitude; whole image contrast improved by ~10.4 times [10]. | Volumetric imaging of vascular dilations in mouse brains in vivo. |

| Correlation-based SMLM (corrSMLM) | > 1.5-fold boost in SBR [12]. | Super-resolution imaging of fixed NIH3T3 cells transfected with fluorescent proteins. |

| Wavefront Shaping with Bessel-Gauss Beam | Enabled precise localization and enhanced hidden fluorescence; provided improved imaging depth and contrast [9]. | Imaging of 40 nm fluorescent beads through various scattering media (pig skin, ground-glass diffusers). |

| Deep Learning Enhanced Dual-Modal Imaging | Improved single-particle lateral resolution by 61% (from 542 nm to 209 nm), indicating a significant effective SBR gain for resolving fine structures [13]. | 3D imaging of UCNPs beyond 500 μm depth in scattering tissue. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

SBR Enhancement Techniques Workflow

Mechanism of Near-Infrared-Excitable Afterglow Nanoparticles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are the 1300 nm and 1700 nm spectral windows particularly advantageous for deep tissue imaging?

These windows leverage a fundamental property of light-tissue interaction: the reduced scattering coefficient of biological tissue at longer wavelengths. As the illumination wavelength increases, light scattering decreases, allowing photons to penetrate deeper into tissue. While the 1300 nm band is a well-established window for this purpose, the 1700 nm band offers a further reduction in scattering and resides in a local minimum of water absorption, leading to even greater penetration depths in turbid tissues [14] [15]. Using these windows significantly improves the signal-to-background ratio by minimizing the scattered light that obscures the desired signal from the focal plane.

Q2: My deep tissue images have a poor signal-to-background ratio. Could the imaging wavelength be a factor?

Yes, this is a likely factor. If you are using wavelengths below 1000 nm, such as those from a standard Ti:Sapphire laser (~800 nm), your imaging depth is limited by significantly higher scattering. This intense scattering creates a large background haze that overwhelms the in-focus signal. Switching to a laser system operating at 1300 nm or 1700 nm is a primary strategy to mitigate this, as it fundamentally reduces the scattering events, thereby improving image contrast and depth [15].

Q3: What is the trade-off when using the 1700 nm window compared to 1300 nm?

The primary trade-off at 1700 nm is increased water absorption. However, for many turbid tissues like the brain, the attenuation of light is dominated by scattering, not absorption. The significant reduction in scattering at 1700 nm can therefore provide a net benefit, yielding a greater imaging depth despite the higher absorption [14]. Furthermore, the 1700 nm window is ideal for exciting fluorophores with two-photon absorption peaks in the infrared region [15].

Q4: I am setting up a 1700-nm OCM system. What is a critical step for achieving high axial resolution?

To achieve high axial resolution, you must use a light source with an extremely broad spectral bandwidth. For example, a system utilizing a supercontinuum source with a 300 nm bandwidth at 1700 nm achieved an axial resolution of 3.8 μm in tissue [16]. Furthermore, proper chromatic dispersion compensation between the sample and reference arms is critical. This is typically done by measuring the group velocity dispersion of the sample arm optics in advance and placing a matching combination of optical glasses in the reference arm [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) at Deep Imaging Depths

Symptoms: Images appear grainy; meaningful biological structures are difficult to distinguish from noise, especially at depths beyond 500 μm.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient illumination power | Use a power meter to measure power at the sample plane. Ensure it is close to but does not exceed the ANSI safety limit (e.g., ~9.6 mW for 1700 nm) [14]. | If safe and possible, increase the laser power. Ensure all optical components (lenses, objective) have high transmission in your operating wavelength band. |

| High sensitivity roll-off (SD-OCM/OCT) | Characterize the sensitivity drop of your spectrometer versus imaging depth. | Implement a full-range imaging technique. This suppresses coherent ghost images and allows you to set the zero-delay position (point of highest sensitivity) inside the sample, thus improving SNR at depth [16]. |

| Suboptimal fluorophore excitation | Consult the two-photon absorption spectrum of your fluorophore. | Match your laser wavelength to the fluorophore's peak excitation. For example, use ~920 nm for GFP/EGFP and ~950 nm for Alexa Fluor 488 [17]. A tunable laser source is ideal for this. |

Problem 2: Poor Spatial Resolution in High-Resolution OCM

Symptoms: Images lack sharpness; fine cellular structures are blurred.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate numerical aperture (NA) | Calculate the theoretical resolution of your objective lens. | Use a high-NA objective lens designed for IR wavelengths (e.g., NA 0.45-0.65). A system with NA 0.45 achieved a lateral resolution of 3.4 μm, while NA 0.65 achieved 1.3 μm [16] [14]. |

| Insufficient source bandwidth | Measure the optical spectrum of your source after all optical components. | For high axial resolution, a broad bandwidth is essential. Use a supercontinuum laser source. A 300 nm bandwidth provides ~3.8 μm axial resolution, while a 380 nm bandwidth can achieve ~2.8 μm [16] [14]. |

| Chromatic dispersion mismatch | Image a mirror surface and check for broadening of the interference signal peak. | Place optical glasses in the reference arm to precisely compensate for the dispersion introduced by the objective lens and other components in the sample arm [14]. |

Quantitative Data for Spectral Windows

The following table summarizes key parameters for deep tissue imaging across different spectral bands, as demonstrated in the search results.

Table 1: Comparison of Imaging Modalities and Key Performance Metrics

| Spectral Band | Imaging Modality | Lateral Resolution (in tissue) | Axial Resolution (in tissue) | Reported Imaging Depth | Key Applications Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1700 nm | Spectral-Domain OCM [16] | 3.4 μm | 3.8 μm | Up to 1.8 mm | Pig thyroid gland imaging |

| 1700 nm | Time-Domain OCM [14] | 1.3 μm | 2.8 μm | Demonstrated superior depth vs. 1300 nm | Mouse brain tissue imaging |

| 1300 nm | Swept-Source OCT [16] | Not Specified | Not Specified | 2.3 mm in living mouse brain | Living brain imaging |

| ~920 nm | Two-Photon Microscopy [17] | Sub-micron (typical for 2PM) | Sub-micron (typical for 2PM) | >600 μm in fixed mouse brain | Neuronal and vascular imaging in hippocampus |

Table 2: Attenuation Properties of Biological Tissue by Wavelength

| Wavelength Band | Scattering Coefficient | Water Absorption | Overall Attenuation in Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~800 nm | High | Low | High (scattering-dominated) |

| 1300 nm | Lower | Moderate | Lower than 800 nm |

| 1700 nm | Lowest | Higher (but has a local minimum) | Can be the lowest in turbid tissues [14] [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Directly Comparing Imaging Depth at 1300 nm vs. 1700 nm

This protocol is based on a methodology used to validate the advantage of the 1700 nm window [14].

Objective: To quantitatively demonstrate that the 1700 nm spectral band provides greater imaging depth than the 1300 nm band under identical sensitivity conditions.

Materials:

- OCM system with interchangeable light sources for 1300 nm and 1700 nm.

- Power meter.

- Standard biological tissue sample (e.g., fixed mouse brain or pig thyroid gland).

- Neutral density (ND) filters.

Method:

- System Setup: Configure the OCM system for the 1300 nm source. Measure the laser power at the sample and adjust with an ND filter if necessary to stay within safety limits.

- Sensitivity Calibration: Measure and record the system's sensitivity in dB.

- 1300 nm Imaging: Acquire a 3D image stack of the tissue sample. Ensure the scan parameters (e.g., number of A-scans, line rate) are recorded.

- Signal Attenuation Analysis: Plot the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) as a function of imaging depth from the acquired data.

- Switch Wavelength: Reconfigure the system for the 1700 nm source. Adjust the reference arm power and dispersion compensation for the new wavelength.

- Power Matching: Measure the power at the sample and use an ND filter to ensure it is identical to the power used for 1300 nm imaging.

- 1700 nm Imaging: Acquire a 3D image stack of the same region of the tissue sample using the same scan parameters.

- Data Analysis: Plot the SNR versus depth for the 1700 nm dataset. Overlay the two plots to compare the rate of SNR decay. The wavelength with a slower decay rate provides a greater imaging depth.

Protocol 2: System Characterization for High-Resolution 1700 nm OCM

Objective: To measure the axial resolution and sensitivity of a 1700 nm OCM system [16] [14].

Materials:

- 1700 nm OCM system with a broadband source.

- Mirror.

- Neutral density filter (e.g., providing ~39 dB attenuation).

- Data acquisition software.

Method:

- Mirror Preparation: Place a mirror in the sample arm. Attach an ND filter in front of it to avoid detector saturation.

- Interference Signal Acquisition: Scan the optical path length in the reference arm (or, for SD-OCM, acquire the spectrum) to record the interference signal from the mirror.

- Axial Resolution Calculation: The axial resolution is measured as the full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the intensity peak of the demodulated (logarithmic) interference signal. A value of 5.2 μm in air corresponds to approximately 3.8 μm in tissue (refractive index n=1.38) [16].

- Sensitivity Calculation: The sensitivity in dB is calculated based on the strength of the measured signal relative to the noise floor, taking into account the known attenuation of the ND filter.

Core Concepts Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Deep Tissue Imaging

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Supercontinuum Laser Source | Provides the broad bandwidth needed for high axial resolution in OCM, especially in the 1700 nm window [16] [14]. | Ensure the source has sufficient power and a smooth spectrum in the desired band (e.g., 300-380 nm bandwidth around 1700 nm). |

| High-NA IR Objective Lens | Focuses light to a small spot for high lateral resolution and collects backscattered light efficiently [16] [14]. | Verify the lens has high transmission at your operating wavelength (e.g., >60% at 1700 nm) and a working distance suitable for your sample. |

| Long-Wavelength Fluorophores | Fluorescent labels excitable at 1300 nm or 1700 nm for two-photon microscopy. | Use dyes or proteins with two-photon absorption peaks in these windows (e.g., SYTOX Orange for 950 nm excitation) to leverage the reduced scattering [17]. |

| Dispersion Compensation Optics | A set of optical glasses (e.g., SF11, BK7) placed in the reference arm of an interferometric system. | Corrects for chromatic dispersion introduced by the sample arm optics, which is critical for maintaining high axial resolution with broadband sources [14]. |

| Fiber-Optic Cannula / Needle Probe | Enables light delivery and collection deep inside tissue for minimally invasive imaging or sensing [18] [19]. | Probes can be miniaturized to fit within a hypodermic needle, allowing access to deep brain structures or other internal tissues. |

Fundamental Principles FAQ

What is intrinsic optical sectioning and how does multiphoton microscopy achieve it? Intrinsic optical sectioning refers to the ability to image thin slices within a thick sample without using a physical pinhole. Multiphoton microscopy achieves this through its nonlinear excitation process. In this process, fluorescence emission depends on the simultaneous absorption of two or more photons, which only occurs at the focal point where photon density is highest. This creates an inherent 3D resolution, as excitation (and thus photobleaching and potential photodamage) is confined exclusively to the focal plane, unlike in confocal microscopy where out-of-focus areas are still excited [20] [21].

How does the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) in multiphoton microscopy benefit deep tissue imaging? Multiphoton microscopy significantly improves SBR in deep tissue for two key reasons. First, the long-wavelength infrared light used for excitation scatters less in biological tissues compared to the shorter wavelengths used in confocal microscopy. This allows the excitation light to penetrate deeper. Second, since fluorescence is generated only at the focal point, there is no out-of-focus background fluorescence to obscure the signal. This combination results in a higher SBR at greater depths, enabling high-resolution imaging of structures like neurons up to 1.8 mm deep in mouse brain tissue [22] [23] [20].

What are the primary causes of photobleaching and phototoxicity, and how does multiphoton microscopy minimize them? Photobleaching (the irreversible destruction of fluorophores) and phototoxicity (damage to living cells) are caused by the interaction of light, particularly high-energy light, with the sample. Multiphoton microscopy minimizes these effects in two ways: 1) It uses long-wavelength infrared light, which has lower energy per photon than the ultraviolet or visible light used in confocal microscopy, reducing the risk of cellular damage. 2) Because excitation is confined to the focal plane, fluorophores above and below the plane are not exposed to the excitation light, thereby preserving the sample's photon budget and health outside the imaged volume [24] [23] [21].

Troubleshooting Guide

Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) at Depth

- Problem: Images appear grainy or unclear when imaging deep within a tissue sample.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Excitation Power: The laser power must be increased with depth to compensate for scattering and maintain signal. However, this must be done precisely to avoid photodamage.

- Solution: Implement an adaptive illumination strategy. Techniques like Learned Adaptive Multiphoton Illumination (LAMI) use a pre-calibrated model to automatically modulate laser power at each point in a 3D volume, providing the minimal power needed for sufficient contrast and conserving the photon budget [24].

- Suboptimal Wavelength: The 1300 nm and 1700 nm spectral bands offer superior penetration in scattering tissues like the brain compared to shorter wavelengths.

- Solution: Where possible, utilize a system capable of operating in the 1700 nm band. Quantitative studies show that 1700 nm OCM can achieve an SBR about 6-times higher than 1300 nm OCM at a depth of 1.5 mm in brain tissue phantoms [22].

- Inefficient Detection: Using a confocal pinhole in a multiphoton setup can unnecessarily reject scattered emission photons that carry useful information.

- Solution: Employ non-descanned detectors (NDDs) placed close to the objective. This configuration allows collection of both ballistic and scattered emission light, maximizing signal collection efficiency, especially from deep, scattering samples [20].

Unsharp or Hazy Images

- Problem: The resulting images lack sharpness and fine detail, even when the system appears to be in focus.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Objective Lens Contamination: Immersion oil or other contaminants on a "dry" objective front lens is a common accident that causes spherical aberration and blurry images.

- Solution: Carefully inspect and clean the objective front lens. Gently remove excess oil with lens tissue, then clean with a solvent like xylol on a cotton swab. Use a degreased brush or air bulb to remove dust afterward [25].

- Incorrect Coverslip Correction: Using a high-numerical-aperture (NA) dry objective with a mismatched coverslip thickness, or misadjusting the objective's correction collar, introduces spherical aberration.

- Solution: Ensure the use of a No. 1½ cover glass (0.17 mm thick). For objectives with a correction collar, adjust it while imaging a sub-resolution fluorescent bead or a sharp sample feature until the signal is maximized and the image is sharpest [25].

- Sample-Induced Aberrations: The refractive index variations in thick tissue can distort the excitation wavefront, blurring the focal spot.

- Solution: Incorporate Adaptive Optics (AO). AO systems measure and correct for sample-induced aberrations in real-time, restoring a diffraction-limited focus for improved resolution and signal strength at depth [1].

Unexpected Photobleaching Patterns

- Problem: Photobleaching occurs in a much larger volume than the focal plane, depleting fluorescence in subsequent imaging rounds.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Saturated Excitation: If the laser power is set too high, it can lead to linear absorption effects or other photodamage, effectively breaking the nonlinear confinement.

- Solution: Use the minimum laser power necessary to achieve an acceptable SNR. Calibrate the power-depth relationship for your specific tissue type to avoid over-illumination [24] [21].

- Pinhole Misconfiguration: If a confocal pinhole is mistakenly left in the detection path on a multiphoton system, it is not the cause of bleaching but may reduce collected signal.

- Solution: Remember that a pinhole is not required for optical sectioning in multiphoton microscopy. For maximum signal collection, especially from scattered photons, the pinhole should be fully open or removed from the light path, and NDDs should be used [20].

Quantitative Data for System Selection

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Imaging Modalities for Deep Tissue

| Parameter | Confocal Microscopy | Two-Photon Microscopy | 1700 nm OCM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Wavelength | Short (UV-Vis) | Long (Infrared, ~700-1000 nm) | Very Long (1700 nm band) |

| Tissue Imaging Depth | ~50-100 μm [23] | ~400-1000 μm [23] | Up to 1.8 mm [22] |

| Optical Sectioning | Pinhole-dependent | Intrinsic (nonlinear excitation) | Intrinsic (coherence gating) |

| Photobleaching/Damage | High (throughout beam path) | Low (confined to focal plane) [23] [21] | Data Not Available |

| SBR in Deep Tissue | Rapidly decreases with depth | High | ~6x higher than 1300 nm at 1.5 mm depth [22] |

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Multiphoton Imaging

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Near-IR Pulsed Laser | Provides high-intensity, short-pulsed light for efficient nonlinear excitation. |

| High-NA Objective | Focuses excitation light to a small volume for high-resolution, efficient multiphoton absorption. |

| Non-Descanned Detectors (NDDs) | Maximize signal collection by capturing both ballistic and scattered emission photons [20]. |

| NIR-II Fluorophores | Fluorescent probes (e.g., certain dyes, proteins, quantum dots) emitting in the 1000-1700 nm window for deeper penetration and reduced scattering [1]. |

| Standard Candle Fluorophores | Cells or beads with identical, stable fluorescent labeling; used to calibrate adaptive illumination models for a given tissue type [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Lateral Resolution with the Nonlinear Knife-Edge Technique

This protocol provides a robust method for characterizing the lateral resolution of a multiphoton microscope with minimal photobleaching [26].

- Sample Preparation: Obtain a GaAs (Gallium Arsenide) wafer. The sharp, cleaved edge of the wafer will serve as the "knife-edge."

- Microscope Setup: Mount the wafer on the microscope stage. Set the laser to the desired wavelength and power for measurement.

- Image Acquisition: Perform a high-resolution line scan perpendicular to the sharp edge of the wafer. Collect the generated Second-Harmonic Generation (SHG) or Third-Harmonic Generation (THG) signal.

- Data Analysis: The intensity profile across the edge will form a sigmoidal curve (edge spread function, ESF). Differentiate the ESF to obtain the line spread function (LSF). The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the LSF is the measured lateral resolution.

Protocol 2: Implementing Learned Adaptive Multiphoton Illumination (LAMI)

This protocol outlines the steps to implement a physics-based machine learning model for optimal power illumination at every point in a 3D sample [24].

- Calibration Sample Preparation: Introduce "standard candle" fluorophores into your tissue type of interest (e.g., by transferring genetically identical, identically labeled lymphocytes into a mouse lymph node).

- Data Acquisition for Training: Image the calibration sample, randomly acquiring data points that include the local sample surface height (shape), XY position in the field of view, the excitation power used, and the resulting detected fluorescence intensity.

- Model Training: Use this dataset to train a neural network to learn the relationship between sample shape, position, excitation power, and the resulting fluorescence. The model learns to predict the tissue-dependent physics of light propagation.

- Application to New Samples: On subsequent experiments with new samples of the same tissue type, use the trained model. The model takes the sample shape and XY position as input and continuously predicts the required excitation power to achieve a desired fluorescence level at each voxel during the scan, minimizing unnecessary photodamage.

System Workflow and Signaling Visualization

Multiphoton Experiment Workflow

Nonlinear Excitation Process

Advanced Imaging Modalities and Computational Tools for Superior SBR

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) in Deep Tissue Imaging

- Symptoms: Images appear noisy, with low contrast between the target structure and the surrounding tissue, especially at depths greater than 1 mm.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause A: The system is operating in a sub-optimal wavelength band.

- Solution: Switch imaging to the 1700 nm spectral band. Quantitative comparisons show that 1700 nm OCM can achieve an SBR about 6-times higher than conventional 1300 nm OCM when imaging through a 1.5 mm-thick tissue phantom [22].

- Cause B: The system sensitivity is insufficient for the imaging depth.

- Solution: Ensure your system sensitivity is optimized. A sensitivity of 100 dB has been used successfully for 1700 nm OCM to achieve a penetration depth of up to 1.8 mm in mouse brain tissue [22].

- Cause C: The sample is causing excessive scattering.

- Solution: Confirm that the optical properties of your sample are suitable. The 1700 nm band is particularly beneficial for tissues with high scattering coefficients, such as brain cortex [22].

- Cause A: The system is operating in a sub-optimal wavelength band.

Problem 2: Degraded Lateral Resolution at Depth

- Symptoms: Loss of fine detail and blurring of image features as the imaging depth increases.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause A: Multiple scattering effects and aberrations in the tissue.

- Solution: Note that while the 1700 nm band significantly improves SBR, the degradation of lateral resolution with depth is similar to that at 1300 nm. The benefit of the 1700 nm band lies primarily in its superior contrast, not in preventing resolution degradation [22].

- Cause B: Use of an objective lens with an inappropriate Numerical Aperture (NA).

- Cause A: Multiple scattering effects and aberrations in the tissue.

Problem 3: Inconsistent System Performance After Switching Wavelengths

- Symptoms: Image quality changes or sensitivity drops when switching between different OCM spectral bands on a hybrid system.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause A: Chromatic dispersion and polarization mismatching between the sample and reference arms.

- Solution: Compensate for chromatic dispersion using optical glasses in the reference arm. Use polarization controllers in both arms to optimize the interference signal [22].

- Cause B: Spectrometer misalignment or non-optimal design for the specific band.

- Solution: Use spectrometers specifically designed for high spectral resolution in your target band. For 1700 nm OCM, a spectrometer with a spectral resolution of 0.09 nm has been successfully implemented [22].

- Cause A: Chromatic dispersion and polarization mismatching between the sample and reference arms.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the 1700 nm spectral band superior to 1300 nm for deep-tissue OCM? The 1700 nm band experiences lower scattering in biological tissue compared to shorter wavelengths. This allows more ballistic photons to return from deeper structures. Furthermore, while light absorption by water is higher at 1700 nm, this property can be advantageous as it preferentially attenuates multiply scattered photons (which contribute to background noise), thereby enhancing the signal-to-background ratio [22] [28] [29].

Q2: What is the typical resolution achievable with 1700 nm OCM? High-resolution 1700 nm OCM systems can achieve an axial resolution of 2.8–3.7 µm and a lateral resolution of 1.3–2.0 µm in tissue, enabling the visualization of fine cellular structures [22] [27] [30].

Q3: What is the maximum penetration depth demonstrated with 1700 nm OCM? Studies have demonstrated high-contrast imaging of a mouse brain at a depth of up to 1.8 mm using 1700 nm spectral domain OCM [22]. Another study using OCM in the 1700 nm band reported a penetration depth of approximately 1 mm [27].

Q4: Are there other beneficial near-infrared imaging windows beyond 1700 nm? Yes, research is exploring even longer wavelengths. The NIR-IIc window (1700–1880 nm) and a proposed window from 1880–2080 nm show promise for high-contrast imaging due to a favorable combination of suppressed scattering and beneficial absorption effects, particularly in environments like adipose tissue [28] [29].

Q5: What type of light source is required for 1700 nm OCM? High-resolution OCM in the 1700 nm band often utilizes supercontinuum (SC) fiber laser sources that provide a broad bandwidth necessary for achieving fine axial resolution [22] [27].

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for OCM in the 1700 nm band as compared to the standard 1300 nm band, based on experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of 1300 nm vs. 1700 nm OCM for Deep-Tissue Imaging

| Performance Metric | 1300 nm OCM | 1700 nm OCM | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) | Baseline | ~6x Higher [22] | Through 1.5 mm brain tissue phantom |

| Penetration Depth | ~1.3–1.8 mm [22] | Up to 1.8 mm [22] | Fixed mouse brain imaging |

| Axial Resolution (in tissue) | N/A | 2.8 µm [27] | System performance measurement |

| Lateral Resolution | N/A | 1.3 µm [27] | System performance measurement |

| System Sensitivity | 100 dB [22] | 100 dB [22] | Measurement with a reflective mirror |

Table 2: Key Specifications of a Hybrid 1300 nm / 1700 nm SD-OCM System

| System Component | Specification for 1300 nm OCM | Specification for 1700 nm OCM |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Polarized Superluminescent Diode (SLD) | Supercontinuum (SC) Fiber Laser [22] |

| Detection Wavelength Range | 1295–1345 nm [22] | 1685–1755 nm [22] |

| Spectrometer Grating | 1210 lines/mm [22] | 940 lines/mm [22] |

| Spectral Resolution | 0.05 nm [22] | 0.09 nm [22] |

| Sensitivity Roll-off | < 4 dB/mm [22] | < 4 dB/mm [22] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantitative Comparison of SBR between 1300 nm and 1700 nm OCM Bands

Objective: To empirically validate the enhancement in Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) when using the 1700 nm spectral band compared to the 1300 nm band.

Materials:

- Hybrid 1300 nm/1700 nm SD-OCM system with shared sample and reference arms [22].

- Reflective resolution test target.

- Tissue phantom with a known scattering coefficient (e.g., similar to brain cortex tissue, ~1.5 mm thick) [22].

Methodology:

- System Setup: Configure the hybrid OCM system to operate at 1300 nm. Ensure the spectrometer and light source are correctly aligned for this band.

- Sample Positioning: Place the resolution test target behind the 1.5 mm-thick tissue phantom in the sample arm.

- 1300 nm Imaging: Acquire an en-face OCM image of the resolution target through the phantom.

- Band Switching: Manually switch the system configuration to the 1700 nm band by changing the fiber connections and flipping the mirror in the spectrometer. Ensure polarization controllers are slightly adjusted to maintain 100 dB sensitivity [22].

- 1700 nm Imaging: Acquire an en-face OCM image at the exact same position on the resolution target through the phantom.

- Data Analysis:

- In the resulting images, select a region of interest (ROI) on a clear signal from the resolution target.

- Select another ROI in a background area where no target feature is present.

- Calculate the SBR for each image using the formula: SBR = Mean(Signal ROI) / Mean(Background ROI).

- Compare the SBR values from the 1300 nm and 1700 nm images.

Expected Outcome: The SBR calculated from the 1700 nm OCM image is expected to be approximately 6 times higher than that from the 1300 nm OCM image, confirming the superiority of the longer wavelength band for imaging through scattering media [22].

Protocol: Deep-Tissue Imaging of Mouse Brain at 1700 nm

Objective: To achieve high-contrast, high-resolution OCM imaging of a fixed mouse brain at depths up to 1.8 mm.

Materials:

- 1700 nm SD-OCM system with a sensitivity of 100 dB [22].

- Fixed mouse brain sample (e.g., from a 12-week-old mouse, perfused and fixed) [22].

- High-NA objective lens (e.g., 0.45 NA) [22].

Methodology:

- System Calibration: Verify the system's resolution and sensitivity by imaging a reflective mirror.

- Sample Mounting: Secure the fixed mouse brain sample in the sample arm.

- Depth Scanning: Acquire volumetric OCM data by scanning the focus and coherence gate together through the depth of the tissue.

- Image Acquisition: Capture en-face images at various depths. The system's auto-focusing feature or manual adjustment should be used to maintain optimal alignment of the confocal and coherence gates at each depth [30].

- Signal Analysis: Evaluate the signal attenuation with depth to determine the effective penetration depth, which can reach up to 1.8 mm [22].

Expected Outcome: Visualization of small structures, such as neurons, in the deep layers of the mouse brain (~1.8 mm depth) with high contrast and cellular resolution [22].

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Diagram 1: 1700 nm OCM Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Photon-Tissue Interaction Mechanism in the 1700 nm Band

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 1700 nm OCM Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Specification/Type |

|---|---|---|

| Supercontinuum (SC) Laser Source | Provides broad-spectrum, high-power illumination in the 1700 nm band. Essential for high axial resolution. | Source covering 1685–1755 nm [22]. |

| High-NA Objective Lens | Focuses the laser beam to a small spot for high lateral resolution. | 0.45 NA IR objective lens [22]. |

| InGaAs Line Scan Camera | Detects the interferometric signal in the spectrometer for Spectral Domain OCM. | Model: SU1024LDH-2.2RT-0250/LC [22]. |

| Tissue Phantom | A standardized scattering medium for calibrating and comparing system performance. | Phantom with scattering coefficient similar to brain cortex, 1.5 mm thick [22]. |

| Fixed Biological Samples | Used for validating deep-tissue imaging capabilities. | Perfusion-fixed mouse brain tissue [22]. |

| Polarization Controllers | Used to optimize the interference contrast by matching polarization states in the interferometer arms. | In-line fiber polarization controllers [22]. |

| Dispersion Compensation Glasses | Correct for chromatic dispersion introduced by optical components, ensuring optimal axial resolution. | Optical glasses placed in the reference arm [22]. |

The Principle: Why 3PM Improves Signal-to-Background Ratio in Deep Tissue

Three-photon microscopy (3PM) is a fluorescence imaging technique that fundamentally enhances the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) for deep-tissue imaging. Its superiority over two-photon microscopy (2PM) stems from its higher-order nonlinear excitation process.

- Excitation Mechanism: In 3PM, a fluorophore absorbs three lower-energy (longer wavelength) photons nearly simultaneously to emit a single, higher-energy fluorescence photon [31] [32]. This process requires a high photon density, confining excitation to a tiny focal volume.

- Superior Background Suppression: The fluorescence signal in 3PM falls off as 1/z⁴ (where z is the distance from the focal plane), compared to 1/z² in 2PM [32] [33]. This drastically reduces out-of-focus background fluorescence, leading to orders of magnitude improvement in SBR at depth [34] [33].

- Reduced Scattering: 3PM typically uses excitation wavelengths in the short-wave infrared (SWIR) range (e.g., 1300 nm or 1700 nm) [34] [35]. These longer wavelengths scatter less in biological tissues than those used for 2PM, allowing the excitation light to penetrate deeper and reach the focal plane more effectively [34].

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of how three-photon excitation leads to a better signal-to-background ratio compared to two-photon excitation.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

This section addresses specific challenges users might encounter during 3PM experiments, providing targeted solutions to improve outcomes.

- Problem: Images appear dim, lack contrast, or require excessively high laser power, suggesting inefficient three-photon excitation.

- Solutions:

- Check Laser Pulse Dispersion:

- Cause: Third-order dispersion (TOD) and other higher-order phase distortions in the laser pulse can prevent compression to the shortest possible duration, drastically reducing the peak intensity needed for efficient 3P excitation [36].

- Action: Use diagnostic tools like second-harmonic generation frequency-resolved optical gating (SHG-FROG) to fully characterize pulse shape and phase, rather than relying on an autocorrelator which cannot quantify TOD [36]. Work with your laser manufacturer to implement appropriate dispersion compensation.

- Optimize Pulse Energy and Duration:

- Cause: Three-photon excitation has a low absorption cross-section and is proportional to the intensity cubed [36] [35].

- Action: Ensure your laser source delivers ultrashort pulses (typically < 100 fs) with high pulse energy (µJ-range) at a lower repetition rate (around 1-4 MHz) to achieve high photon density without excessive average power that would heat the sample [31] [35].

- Check Laser Pulse Dispersion:

Issue 2: High Background or Low Contrast at Depth

- Problem: Images become blurry and lack contrast when imaging deep into tissue, despite sufficient signal from the focal plane.

- Solutions:

- Verify Detection Filter Optical Density (OD):

- Cause: The fluorescence efficiency in 3PM is extremely low (10⁻⁷ to 10⁻⁸). Inadequate blocking of the intense excitation light will swamp the weak fluorescence signal [37].

- Action: Ensure your detection path has a combined optical density (OD) of at least 8 at the excitation wavelength. This requires high-quality dichroic mirrors, laser-blocking filters, and emission filters [37].

- Confirm Wavelength Suitability:

- Verify Detection Filter Optical Density (OD):

Issue 3: Sample Heating or Photodamage

- Problem: Signs of tissue damage, bleached samples, or altered physiological responses during in vivo imaging.

- Solutions:

- Adhere to Safe Pulse Energy Limits:

- Cause: Excessive pulse energy at the focus can cause optical breakdown, saturate fluorophores, and induce physiological changes [38].

- Action: For functional imaging with GCaMP6s in the mouse brain, keep pulse energies below 2 nJ to avoid saturation and preserve accurate physiological responses. Pulse energies above 5-10 nJ risk visible tissue damage and optical breakdown [38].

- Manage Average Power and Water Absorption:

- Cause: SWIR light, particularly in the 1700 nm window, is absorbed more strongly by water, potentially leading to sample heating [31].

- Action: The 1300 nm window offers a favorable trade-off with 2x less scattering and 2x more absorption than other windows, often requiring less average power overall [31]. Always use the minimum average laser power necessary to achieve a usable SBR.

- Adhere to Safe Pulse Energy Limits:

Table: Safety and Damage Thresholds for In Vivo 3PM Imaging in Mouse Brain

| Pulse Energy | Observed Effect | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 - 2 nJ | Safe for physiological recording; accurate neuronal response [38]. | Ideal range for functional imaging. |

| 2 - 5 nJ | Initiation of GCaMP6s saturation; reduced response intensity [38]. | Avoid for quantitative functional studies. |

| > 5 - 10 nJ | Optical breakdown; visible tissue damage [38]. | Danger zone. Will damage the sample. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary limitations of three-photon microscopy? The main challenges are:

- Laser Requirements: The need for complex, high-power laser systems (often involving OPAs) that deliver µJ-energy, sub-100 fs pulses at low (MHz) repetition rates [31] [35].

- Cost: These specialized laser sources and objectives with high SWIR transmission are expensive [31].

- Pulse Fidelity: Image quality is highly sensitive to laser pulse distortions, requiring careful characterization and management of dispersion [36].

- Potential Heating: Longer wavelengths, especially around 1700 nm, have higher water absorption, necessitating careful power management to avoid thermal effects [31].

Q2: Can I use the same fluorescent indicators for 3PM as I do for 2PM? Yes, many common genetically encoded indicators like GFP, GCaMP, and RFP variants (mCherry, tdTomato) can be used with 3PM [34] [35]. However, the excitation wavelength must be optimized for three-photon absorption (e.g., ~1300 nm for GFP/GCaMP, ~1700 nm for RFP) [35].

Q3: What is a typical imaging depth for 3PM in the mouse brain? 3PM enables high-resolution imaging at depths beyond the reach of 2PM. It readily allows imaging of the hippocampus and other subcortical structures at depths exceeding 1 mm in the intact mouse brain [34] [32]. In the highly scattering mouse spinal cord, 3PM enables imaging to depths of ~550 μm [39].

Q4: Is it possible to do multicolor 3PM imaging? Yes, simultaneous multicolor imaging is achievable. This typically requires a laser source that can emit multiple wavelength bands (e.g., both 1300 nm and 1700 nm) to efficiently excite different fluorophores [35]. With a single excitation wavelength, multicolor imaging is still possible but may be less efficient for some probes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful 3PM experiments rely on a specific set of reagents and hardware. The table below details key components for a typical in vivo imaging setup.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Three-Photon Microscopy

| Item | Function / Role | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SWIR Laser Source | Provides high-intensity, ultrashort pulses for 3P excitation. | Optical Parametric Amplifier (OPA); Wavelength: 1300 nm or 1700 nm; Pulse Duration: <100 fs; Rep Rate: 1-4 MHz [31] [35]. |

| High-NA IR Objective | Focuses excitation light and collects emitted signal; must transmit SWIR wavelengths. | Water-immersion objectives (e.g., Olympus XLPLN25XWMP2, Nikon/Olympus LWD objectives); High transmission >65% at 1300-1700 nm [35] [37]. |

| Genetically Encoded Indicators | Label specific cell types or report physiological activity. | GCaMP (calcium), GFP (structure), tdTomato/mCherry (structure, second label) [34] [35] [38]. |

| High-OD Detection Filters | Block scattered excitation light to detect weak fluorescence signal. | Dichroic mirrors and bandpass filters with a combined OD > 8 at the excitation wavelength (e.g., 1300/1700 nm) [37]. |

| Sensitive Detectors | Capture low-light-level fluorescence emission. | GaAsP Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs) in non-descanned detection mode [35] [37]. |

The workflow for planning and executing a 3PM experiment involves several key stages, from sample preparation to data acquisition, as summarized below.

This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers implementing Lightsheet Line-scanning SIM (LiL-SIM), a cutting-edge method that upgrades conventional two-photon laser-scanning microscopes for super-resolution deep tissue imaging. By combining two-photon excitation with patterned line-scanning and computational reconstruction, LiL-SIM achieves up to a twofold resolution enhancement, allowing imaging of sub-cellular structures down to at least 70 µm deep in scattering tissues [6]. The content herein addresses common experimental challenges, framed within the core thesis of optimizing the signal-to-background ratio, a critical parameter for successful deep tissue research.

Key Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

The fundamental innovation of LiL-SIM lies in its simple and cost-effective implementation. The core protocol involves integrating three key hardware components into a standard two-photon laser-scanning microscope and employing a specific acquisition sequence [6].

Hardware Integration

The following components are added to the microscope's optical path:

- A cylindrical lens: Focuses the round laser beam into a line at the back focal plane of the objective.

- A field rotator (e.g., a Dove prism): Enables the rotation of the line-focus illumination pattern across multiple orientations (e.g., 0°, 60°, and 120°) to ensure isotropic resolution enhancement. Rotating the Dove prism by an angle α results in a 2α rotation of the optical field.

- A sCMOS camera with a lightsheet shutter mode (LSS): Used for detection. The LSS mode acts as a dynamic slit, opening only for the currently illuminated line on the sample, thereby dramatically rejecting scattered light from out-of-focus planes and improving the detected modulation contrast [6].

Image Acquisition and Synchronization

Unlike conventional SIM that uses full-field interference patterns, LiL-SIM builds the final pattern line-by-line [6].

- The galvanometric scanners step a single line-focus across the field of view.

- For each pattern orientation, multiple images are acquired with precise phase shifts of the illumination line.

- The field rotator and the camera's LSS mode are synchronized with the scanner position to ensure optimal pattern orientation and background rejection.

- This sequential line-scanning approach reduces the required laser power compared to full-field illumination and is less sensitive to sample-induced aberrations and scattering.

Image Reconstruction

After acquiring multiple raw images with different pattern orientations and phases, a computational reconstruction process is applied. This process separates the superimposed frequency information to generate a final image with a lateral resolution of approximately 150 nm, effectively doubling the resolution of the base microscope [6] [40].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common LiL-SIM Experimental Issues

Q1: I have implemented LiL-SIM, but the reconstructed image has severe artefacts or the reconstruction fails. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Low modulation contrast in the raw images.

- Solution: The success of SIM reconstruction is highly dependent on a high-contrast illumination pattern. Check the following:

- Polarization: Ensure the linear polarization of the laser is perpendicular to the central line-focus at the back aperture to prevent depolarization and loss of contrast. A half-wave plate mounted on the rotation stage can correct for polarization changes introduced by the Dove prism [6].

- LSS Synchronization: Verify that the orientation of the camera's exposure band (LSS mode) is perfectly aligned with the illumination line on the sample. A deviation of more than a few milliradians will cause uneven detection across the field of view [6].

- Sample Scattering: For very deep tissue imaging, scattering can degrade the detected modulation. Ensure you are using the LSS mode, as it is specifically designed to enhance modulation contrast in such conditions [6].

Q2: The signal-to-background ratio in my deep tissue images is poorer than expected. How can I improve it?

- Problem: Excessive background fluorescence from out-of-focus planes and scattered light.

- Solution:

- Confirm LSS Operation: The primary tool for background suppression in LiL-SIM is the lightsheet shutter mode. Double-check that it is activated and correctly synchronized. This mode makes background signal decay with the 4th power of the distance from the focal plane, providing superior optical sectioning [6] [41].

- Leverage Two-Photon Excitation: Remember that two-photon excitation itself provides inherent optical sectioning, as fluorescence is only generated at the focal spot. Ensure your laser is properly aligned and focused [41] [40].

- Check Sample Preparation: Refractive index mismatches between immersion media, mounting media, and the sample can introduce spherical aberrations, reducing image quality. Use immersion media matched to your sample where possible [42].

Q3: My imaging penetration depth is limited. What factors can I adjust to image deeper?

- Problem: Signal attenuation and aberration in thick, scattering tissues.

- Solution:

- Utilize Adaptive Optics (AO): While not part of the basic LiL-SIM setup, incorporating a deformable mirror (DM) can correct for sample-induced aberrations. AO has been shown to enable high-quality SIM imaging at depths exceeding 130 µm by restoring resolution and contrast [42].

- Optimize Pattern Spacing: The flexibility of LiL-SIM allows the pattern spacing to be set by the control voltage of the scanner. Experiment with different spacings to find the optimal setting for your specific objective lens and imaging depth [6].

- Consider Multi-Photon Power: While LiL-SIM reduces power requirements via line-scanning, ensure your laser source provides sufficient peak power for effective two-photon excitation at greater depths.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How does LiL-SIM improve the signal-to-background ratio compared to a standard confocal microscope? A: It uses a multi-faceted approach. First, two-photon excitation limits fluorescence generation to the focal volume. Second, and most critically, the camera's lightsheet shutter mode (LSS) selectively detects light only from the thin, currently illuminated line, rejecting almost all out-of-focus and scattered light. This combined effect results in a much higher signal-to-background ratio, crucial for deep tissue imaging [6] [41].

Q: What is the typical resolution improvement I can expect with LiL-SIM? A: LiL-SIM typically provides an up to twofold enhancement in lateral resolution. This can improve resolution from a diffraction-limited ~300 nm down to approximately 150 nm, allowing visualization of fine sub-cellular structures like microtubules and organelles [6] [40].

Q: Can I use LiL-SIM with my existing fluorescent markers? A: Yes, a significant advantage of LiL-SIM and SIM techniques in general is their compatibility with conventional fluorophores, unlike some other super-resolution methods that require special dyes or proteins [43] [42].

Q: My reconstruction is slow and computationally demanding. Are there alternatives? A: Yes, new computational methods are being developed. For example, ML-SIM is a deep learning-based reconstruction tool that uses a residual neural network to reconstruct images in less than 200 ms on a modern GPU. It is also more robust to noise and irregularities in the illumination pattern [44].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Resolution Performance of LiL-SIM and Related Techniques in Deep Tissue

| Microscopy Method | Lateral Resolution | Axial Resolution | Demonstrated Penetration Depth | Key Advantage for Deep Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiL-SIM [6] | ~150 nm | Information Missing | >70 µm | Cost-effective upgrade; LSS mode for background rejection |

| 2P ISIM [40] | ~150 nm | ~400 nm | >100 µm | High speed (~1 Hz); inherent optical sectioning |

| Deep3DSIM (with AO) [42] | ~185 nm | ~547 nm | >130 µm | Adaptive optics corrects aberrations; upright configuration |

| Standard Confocal | ~250 nm | ~500-700 nm | Varies | Widely available; good optical sectioning |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LiL-SIM Imaging

| Reagent / Material | Function in LiL-SIM Experiment | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| sCMOS Camera with LSS Mode | Critical for detection; its rolling shutter provides optical sectioning by blocking scattered light from out-of-focus planes. | Core detection component [6]. |

| Cylindrical Lens | Shapes the round laser beam into a line focus to create the structured illumination pattern. | Placed in the excitation path to focus light into the objective's back focal plane [6]. |

| Field Rotator (Dove Prism) | Rotates the illumination and detection field to acquire pattern orientations necessary for isotropic resolution enhancement. | Mounted on a rotation stage in the shared excitation/detection path [6]. |

| High-NA Water Immersion Objective | Provides high resolution and a better refractive index match to biological tissues, reducing spherical aberration at depth. | Used in Deep3DSIM for imaging deep into Drosophila brains [42]. |

| Adaptive Optics (Deformable Mirror) | Corrects for sample-induced aberrations that degrade image quality and resolution in thick tissues. | Added to the optical path in advanced systems like Deep3DSIM to enable deep imaging [42]. |

LiL-SIM Experimental Workflow and Signal Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflow of a LiL-SIM system, from hardware integration to final super-resolved image output.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues with LRDM-3PM Implementation

Issue 1: Persistent Structured Noise in Reconstructed Images

- Problem: After processing with LRDM, images still show ripple-like artifacts or stripe patterns.

- Cause: This occurs when the low-rank (LR) denoiser component is not effectively separating the structured noise (e.g., from the PMT) from the vascular signals before the diffusion model is applied [45].

- Solution:

- Verify that the LR-denoiser is activated as a preprocessing step.

- Manually inspect the output of the LR-denoiser alone to confirm it is removing the stripe features without erasing faint vascular signals [45].

- Ensure the raw data contains sufficient signal; excessive noise may overwhelm the initial denoising step.

Issue 2: Low Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) at Extreme Depths

- Problem: The SBR of enhanced images remains low (e.g., below 10) at depths beyond 1.3 mm.

- Cause: The primary cause is an insufficient number of photons (weak fluorescence signal) reaching the detector, leading to a high degree of random noise that challenges the model's denoising capability [45].

- Solution:

- Confirm the use of bright AIE nanoprobes with a large three-photon absorption cross-section to maximize signal generation at depth [45].

- Ensure the self-supervised training of the diffusion model leverages high-quality, augmented superficial data that accurately represents the scattering profile of your sample [45].

- Check that the U-Net within the diffusion model was trained with adequate data augmentation to learn the specific noise characteristics of your 3PM system (see Fig. S2 in Supplementary Material of [45]).

Issue 3: Model Generates "False" Vessel Structures

- Problem: The output images show vessel-like patterns that do not correspond to real biological structures.

- Cause: This is often a result of the diffusion model learning and amplifying the structured background noise, mistaking it for signal [45].

- Solution:

- This issue is specifically mitigated by the LR-denoiser. Revisit the solution for Issue 1 to ensure structured noise is removed upfront [45].

- Validate your results against a ground truth dataset or a different imaging modality if possible.

- Adjust the parameters of the LR matrix decomposition to be more aggressive in removing structured components [45].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of using a self-supervised deep learning approach like LRDM over supervised methods for 3PM? A1: Supervised methods, like DnCNN, require paired datasets (noisy and clean images of the same field), which are extremely difficult to obtain for deep tissue imaging. LRDM utilizes a self-supervised framework that can learn from the superficial, high-quality information within the 3D image sequence itself, eliminating the need for perfectly paired training data and improving generalization on real-world data [45].

Q2: Why does LRDM combine a diffusion model with a separate low-rank denoiser? A2: The complex noise in deep 3PM is a mixture of random (photon) noise and structured noise (e.g., ripple patterns from line scanning). Standard denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) are designed for random noise and can fail on structured noise, sometimes even reproducing it. The LR-denoiser is specifically designed as a preprocessing step to remove this structured noise, preventing the diffusion model from amplifying it and allowing the diffusion model to focus on suppressing random noise and signal restoration [45].

Q3: What SBR performance can we realistically expect when imaging the hippocampus of a live mouse? A3: When implemented correctly with bright AIE nanoprobes, the LRDM-3PM method has been demonstrated to achieve a remarkable SBR above 100 at depths of up to 1.5 mm, which is sufficient for high-contrast imaging of the hippocampus in a live mouse brain [45].

Q4: My GPU memory is insufficient for training the LRDM model. What are my options? A4: This is a common challenge in deep learning. You can:

- Reduce the batch size during training to lower memory consumption.

- Implement mixed precision training, which uses lower-precision data types to speed up computations and reduce memory demands without significant loss of accuracy [46].

- Use gradient accumulation to simulate a larger batch size.

- If available, leverage distributed training across multiple GPUs to share the memory load [46].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Comparison of Denoising Performance in Deep Mouse Brain Imaging (≥ 900 μm depth) [45]

| Method | Structured Noise Removal | Random Noise Suppression | Typical SBR Achieved | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Averaging | Poor | Moderate | Low | Can exacerbate stripe appearance; long acquisition [45] |

| Previous DDPM | Poor (may amplify) | Good | Medium | Can generate false vessels from structured noise [45] |

| LR-denoiser Alone | Excellent | Poor | Low | Does not address random photon noise [45] |