Strategies to Reduce Tissue Autofluorescence in NIR Imaging: A Guide for Enhanced Biomedical Research

Near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging, particularly in the NIR-II window (1000–1700 nm), is revolutionizing biomedical research and drug development by enabling deep-tissue visualization with high resolution.

Strategies to Reduce Tissue Autofluorescence in NIR Imaging: A Guide for Enhanced Biomedical Research

Abstract

Near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging, particularly in the NIR-II window (1000–1700 nm), is revolutionizing biomedical research and drug development by enabling deep-tissue visualization with high resolution. However, tissue autofluorescence remains a significant challenge, undermining image contrast and the accuracy of data interpretation. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the sources of autofluorescence and evidence-based strategies to minimize it. We cover foundational principles, practical methodological adjustments, advanced optimization techniques, and validation protocols. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource aims to empower professionals to design robust imaging experiments, improve signal-to-background ratios, and accelerate the translation of NIR imaging technologies into clinical applications.

Understanding the Enemy: The Sources and Impact of Tissue Autofluorescence

Autofluorescence (AF) is the natural emission of light by biological structures when excited by specific wavelengths of light, a phenomenon stemming from endogenous molecular components known as intrinsic fluorophores [1] [2] [3]. In biomedical research, particularly in fluorescence microscopy, autofluorescence can be a significant confounding factor, creating a background signal that obscures specific signals from applied fluorescent labels [1] [4]. Understanding the sources of autofluorescence—categorized as intrinsic (from the biological tissue itself) and extrinsic (from preparation reagents or materials)—is the first critical step in developing strategies to mitigate its effects. This guide provides a structured, practical approach to identifying and managing autofluorescence, with a special emphasis on leveraging Near-Infrared (NIR) imaging to enhance research outcomes.

FAQ: Understanding Autofluorescence

1. What is autofluorescence and why is it a problem in imaging? Autofluorescence is the inherent fluorescence emitted by biological molecules or foreign substances within a sample when illuminated by light of a specific wavelength [1] [3]. It is problematic because it creates a background signal that can interfere with and obscure the detection of specific fluorescent signals from applied dyes or tags (e.g., fluorescently labelled antibodies), thereby reducing image contrast, clarity, and the overall signal-to-noise ratio [1] [4] [5].

2. What are the most common intrinsic sources of autofluorescence? The most common intrinsic sources are endogenous fluorophores present within cells and tissues. Key contributors include [1] [4] [2]:

- NAD(P)H: A metabolic coenzyme found in the cytoplasm and mitochondria. Its fluorescence is indicative of the cellular metabolic state. Only the reduced form, NAD(P)H, is fluorescent [3].

- Flavins (FAD): Another metabolic coenzyme, primarily located in the mitochondria. In contrast to NAD(P)H, the oxidized form (FAD) is the primary fluorescent species [3].

- Structural Proteins: Collagen and elastin, major components of the extracellular matrix, are highly autofluorescent and are frequently encountered in tissue imaging [1] [3].

- Lipofuscin: An intralysosomal, undegradable pigment that accumulates with age in various cell types (e.g., neurons, cardiac muscle). It exhibits broad excitation and emission spectra [1] [3].

- Aromatic Amino Acids: Tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine within proteins contribute to autofluorescence, particularly when excited by UV light [1] [4].

- Melanin: The natural skin and hair pigment, which has photoprotective functions [1] [3].

- Porphyrins: Organic compounds that can accumulate in tissues and act as tumor markers [2] [6].

Table 1: Spectral Properties of Common Endogenous Fluorophores

| Endogenous Fluorophore | Primary Biological Role | Excitation Peak (nm) | Emission Peak (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H [3] | Metabolic coenzyme | 340 | 450 |

| Flavins (FAD) [3] | Metabolic coenzyme | 380-490 | 520-560 |

| Collagen [3] | Structural protein | 270 | 390 |

| Elastin [3] | Structural protein | 350-450 | 420-520 |

| Lipofuscin [1] | Age pigment | 410-470 | 500-695 |

| Tryptophan [3] | Amino acid | 280 | 350 |

| Melanin [1] | Pigment | 340-400 | 360-560 |

3. What are common extrinsic sources of autofluorescence? Extrinsic autofluorescence originates from non-biological materials used in sample preparation and handling [3]:

- Fixatives: Aldehyde-based fixatives like glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde can create fluorescent crosslinks between proteins [2] [3].

- Culture Media: Additives such as phenol red can significantly increase background fluorescence [3].

- Plastics: The plastic in petri dishes, well plates, and cell culture flasks often fluoresces broadly [3].

- Paper and Adhesives: Paper labels or stickers used on slides or containers are highly fluorescent and should be kept away from the imaging area [3].

4. How does NIR imaging help reduce autofluorescence? Near-Infrared (NIR) imaging, particularly in the NIR-II window (1000–1700 nm), dramatically reduces autofluorescence interference because most endogenous fluorophores have excitation and emission spectra in the UV-visible range (below ~700 nm) [7] [5]. Shifting excitation and emission detection to the NIR region minimizes the excitation of these intrinsic fluorophores, resulting in a much lower background, deeper tissue penetration, and higher signal-to-background ratios [7] [5].

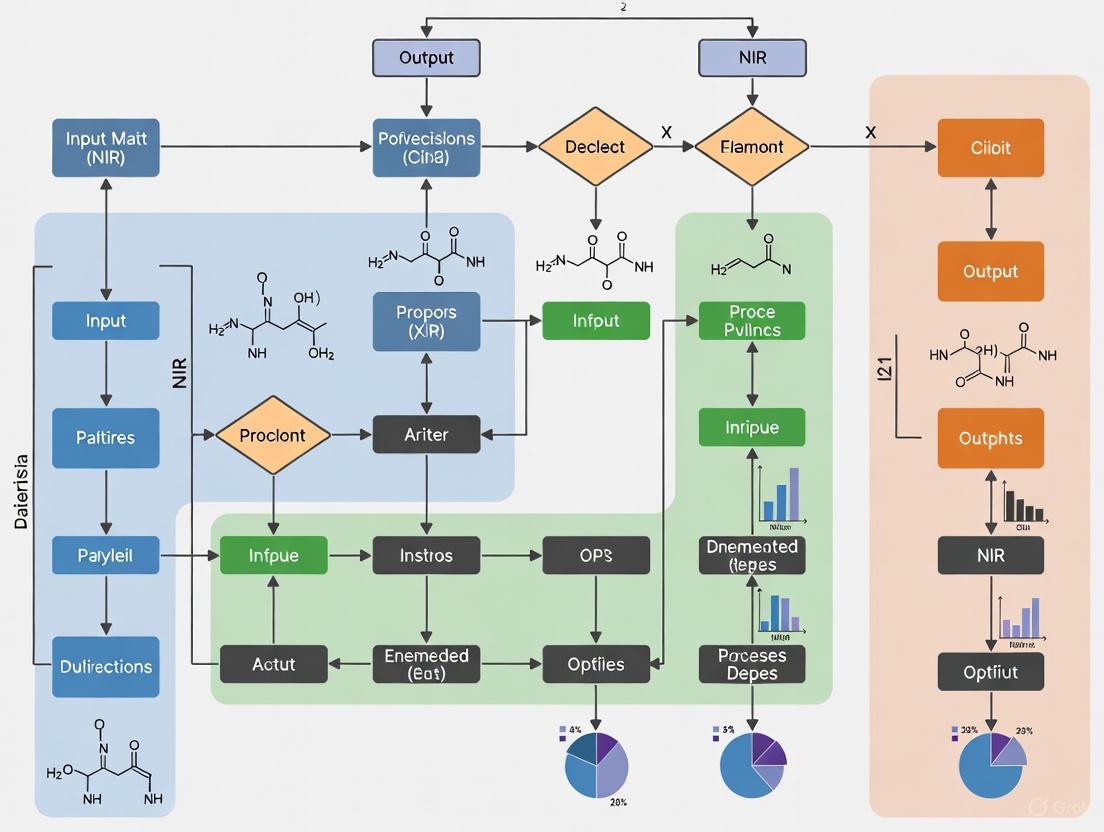

Diagram 1: Autofluorescence decreases in NIR windows, improving contrast.

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating Autofluorescence

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for diagnosing and addressing autofluorescence in your experiments.

Step 1: Diagnosis and Identification

Objective: Confirm that the observed background signal is indeed autofluorescence.

- Method: Image an unstained control sample (no fluorescent dyes or antibodies applied) under your standard imaging conditions.

- Expected Outcome: If you observe a signal in the unstained control, it is autofluorescence. Note its intensity, distribution, and spectral profile.

- Advanced Technique: Perform microspectrofluorometry to acquire the full emission spectrum of the autofluorescent signal at various excitation wavelengths. This can help identify the specific fluorophore responsible [2] [6].

Step 2: Pre-imaging Mitigation Strategies

Objective: Minimize autofluorescence before data acquisition.

- Strategy A: Chemical Reduction

- Protocol: For aldehyde-induced fluorescence, treat samples with a reducing agent like sodium borohydride (0.1% w/v in PBS for 30 minutes) after fixation to reduce fluorescent crosslinks [2].

- Considerations: Test this protocol on a small sample first, as it can affect some epitopes.

- Strategy B: Photobleaching

- Protocol: Excite the unstained sample with a high-intensity light source at the wavelength that produces the strongest autofluorescence for a prolonged period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) prior to staining and imaging. This can "bleach" the autofluorophores [2].

- Considerations: This is not suitable for live-cell imaging and may cause photodamage.

- Strategy C: Use NIR Fluorophores

- Protocol: Design your experiment to use fluorescent probes that excite and emit in the NIR range (e.g., Cy7, Alexa Fluor 750, IRDye 800CW) to avoid the excitation windows of most autofluorophores [7] [3] [5].

- Example: As demonstrated in one study, labeling oligodendrocytes with LiCor IRDye 800CW and imaging with 730 nm excitation effectively avoided lipofuscin autofluorescence in an aged rat brain slice [5].

Step 3: Instrument-based Solutions During Imaging

Objective: Separate the specific signal from autofluorescence during acquisition.

- Strategy A: Spectral Unmixing

- Protocol: Acquire the emission spectrum (a "fingerprint") of both the autofluorescence (from your unstained control) and your specific fluorophore. Use software algorithms to then unmix the signals from your stained sample based on their distinct spectral profiles [3].

- Strategy B: Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM)

- Protocol: Utilize the fact that autofluorophores and your applied fluorophore often have different fluorescence lifetimes (the time a molecule remains in the excited state). FLIM measures this lifetime, allowing for discrimination based on temporal characteristics rather than just intensity or color [4] [8].

- Example: A study successfully used lifetime gates to suppress unspecific gastrointestinal autofluorescence and specifically detect a Cy5.5-labeled antibody in a pancreatic tumor model [4].

- Strategy C: Optical Clearing

- Protocol: Use optical clearing agents like Ethyl Cinnamate (ECi) to render tissues transparent. This reduces light scattering and absorption, which can amplify the effects of autofluorescence, and allows for cleaner imaging of deep structures [9].

Step 4: Post-processing Corrections

Objective: Subtract residual autofluorescence after image acquisition.

- Method: Background Subtraction

- Protocol: Acquire an image of the autofluorescence background from an unstained control region or sample. Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Fiji) to subtract this background image from your experimental images.

- Considerations: This method works best when the autofluorescence is uniform and of low intensity.

Diagram 2: A systematic workflow for troubleshooting autofluorescence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Autofluorescence Management

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Borohydride [2] | Reduces fluorescent crosslinks formed by aldehyde fixatives. | Post-fixation treatment of tissue sections to reduce background. |

| Phenol Red-Free Media [3] | Eliminates culture media as a source of autofluorescence. | Live-cell imaging of cultured cells or organoids. |

| Ethyl Cinnamate (ECi) [9] | A non-hazardous optical clearing agent; reduces light scattering. | Clearing murine liver, knee, or ocular tissues for 3D light sheet fluorescence microscopy. |

| NIR Fluorophores (e.g., Cy7, Alexa Fluor 750) [7] [3] | Shift excitation/emission beyond the range of most autofluorophores. | In vivo imaging or deep-tissue microscopy to achieve high contrast. |

| Glass-Bottom Dishes/Plates [3] | Avoid the broad autofluorescence emitted by plastic cultureware. | Any high-resolution fluorescence imaging of live or fixed cells. |

| Non-aldehyde Fixatives [3] | Prevent the creation of new fluorescent compounds during fixation. | Alternative tissue fixation for samples destined for sensitive fluorescence detection. |

| DBCO-PEG1-NH-Boc | DBCO-PEG1-NH-Boc, MF:C28H33N3O5, MW:491.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Phyperunolide E | Phyperunolide E, MF:C28H40O9, MW:520.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Autofluorescence (AF) is the emission of light by endogenous biological molecules, or fluorophores, when excited with specific wavelengths of light. In the context of Near-Infrared (NIR) imaging, AF creates a background signal that can obscure the specific signal from applied fluorescent probes, reducing sensitivity and quantitative accuracy. This technical guide helps researchers identify key sources of AF and provides methodologies to mitigate their effects.

The main endogenous fluorophores that contribute to background signal in biological tissues, along with their characteristic spectral ranges, are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Primary Endogenous Fluorophores and Their Spectral Profiles

| Endogenous Fluorophore | Biological Role | Typical Excitation Range (nm) | Typical Emission Range (nm) | Common Tissue Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H [4] [2] | Coenzyme in redox metabolism | 330 - 380 | 440 - 462 (bound/free) | Cell cytoplasm, mitochondria |

| Flavins [4] [2] | Coenzymes (e.g., FAD) | 350 - 450 | 480 - 540 | Cell cytoplasm, mitochondria |

| Collagen & Elastin [4] [2] | Extracellular matrix structural proteins | 330 - 420 | 400 - 510 | Connective tissue, skin, vessels |

| Aromatic Amino Acids [4] [2] | Tryptophan, Tyrosine, Phenylalanine | 240 - 280 | 280 - 350 | Most proteins |

| Chlorophyll [9] | Plant photosynthetic pigment | ~405 - 640 (broad) | ~670 - 730 (broad) | Plant-based diet residues |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is autofluorescence a significant problem in NIR imaging for drug development? Autofluorescence creates a non-specific background signal that can severely limit the sensitivity and accuracy of detecting specific signals from targeted NIR probes. This is critical in pre-clinical studies for quantifying drug distribution, target engagement, and treatment efficacy, where a low signal-to-noise ratio can lead to inaccurate data [4] [10].

2. Can I completely eliminate autofluorescence from my tissue samples? While it is challenging to eliminate it entirely, autofluorescence can be significantly reduced and managed through a combination of careful sample preparation, strategic optical filtering, and advanced imaging techniques that exploit differences in fluorescence lifetime between AF and your probe [4] [2].

3. My samples are from plant-fed animals. Could their diet affect my imaging? Yes. Chlorophyll and its metabolites from a plant-based diet can be present in animal tissues and are highly fluorescent across a broad range of wavelengths, including the visible and NIR spectrum. This can contribute to unexpected background signals [9].

4. How does chemical fixation like with formaldehyde affect autofluorescence? Aldehyde-based fixatives (e.g., formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde) are known to induce autofluorescence by forming fluorescent condensation products with amines and proteins. This can increase the overall background signal, particularly in the blue-green spectral region [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High, unstructured background in images, making specific signal quantification difficult.

Solution: Systematically characterize the AF profile of your target tissue.

Experimental Protocol: AF Spectral Characterization [9]

- Sample Preparation: Use unstained, non-perfused tissue samples from your model organism (e.g., murine liver, knee, ocular globe).

- Optical Clearing (Optional but Recommended): Render tissues transparent to improve light penetration.

- Reagent: Ethyl Cinnamate (ECi) - A non-hazardous, low-cost alternative to toxic solvents like BABB [9].

- Protocol: After fixation (e.g., 4% PFA), dehydrate samples through a graded ethanol series, then clear by immersion in ECi until transparent.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire images across multiple excitation wavelengths (e.g., 405 nm, 488 nm, 561 nm, 640 nm, 785 nm) using a system like Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM). Keep laser power and camera settings consistent.

- Data Analysis:

- Measure fluorescence intensity profiles (Edge-Raise-Distance) across different tissue structures.

- Use software (e.g., Fiji/ImageJ) to analyze the AF spectrum of specific regions of interest.

- Compare AF signals at different tissue depths, as shorter wavelengths (405, 488 nm) may provide better detail at shallow depths, while longer wavelengths (640, 785 nm) penetrate deeper with less scattering [9].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Autofluorescence Identification

| Symptom | Possible Culprit | Confirmatory Test |

|---|---|---|

| Strong blue-green emission | NAD(P)H, Flavins, Aldehyde fixation | Acquire with 350-380 nm excitation; note if fixation increased signal [4] [2]. |

| Signal in connective tissue, skin, vessels | Collagen/Elastin | Image with 330-420 nm excitation; signal should be prominent in extracellular matrix [4] [2]. |

| Broad signal in liver cytoplasm, metabolic zones | NAD(P)H | Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) can separate NADH from other signals [11] [2]. |

| Signal in gastrointestinal tract or from plant-based diet | Chlorophyll metabolites | Image with 640-660 nm excitation and look for emission in the NIR region [9]. |

Guide 2: Mitigating and Quenching Autofluorescence

Problem: After characterization, AF remains too high for clear specific signal detection.

Solution: Implement strategies to reduce AF intensity.

Experimental Protocol 1: Chemical Quenching of NADH Fluorescence [11]

- Principle: The fluorescence of NADH can be quenched when it binds to specific enzymes and substrates, a process involving an electron transfer mechanism.

- Method: In studies of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), the substrate mimic oxamate acts as an electron acceptor, quenching NADH fluorescence in the LDH-NADH-oxamate ternary complex.

- Application: This mechanistic knowledge can be exploited in cell-based assays where NADH is a major contributor to background. Introducing specific enzyme-substrate pairs could provide a targeted quenching strategy.

Experimental Protocol 2: Chemical Reduction of Glutaraldehyde-Induced AF [12]

- Problem: Glutaraldehyde (GTA) fixation or crosslinking introduces free aldehyde groups that cause high levels of unwanted AF.

- Quenching Solution:

- Sodium Borohydride (SB): Prepare a 1% (wt/vol) solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Handle with care; can produce hydrogen gas.

- Sodium Metabisulfite (SM): Prepare a 1% (wt/vol) solution in PBS.

- Protocol: After GTA treatment, incubate samples in the chosen quenching solution.

- SB Incubation: 10 minutes at room temperature with constant shaking.

- SM Incubation: 1 hour at room temperature with constant shaking.

- Post-treatment: Wash samples rigorously with PBS after treatment. This method has been shown to restore biocompatibility and reduce cytotoxicity associated with GTA [12].

Experimental Protocol 3: Optical & Computational AF Reduction [9] [4] [10]

- Spectral Unmixing: Use probes with narrow emission spectra distinct from the major AF components. Acquire images in multiple channels and use software to mathematically separate the specific signal from the AF background.

- Time-Gated Imaging / FLIM: Exploit differences in fluorescence decay times.

- Principle: Many endogenous fluorophores have short lifetimes (e.g., collagen: 0.2-0.4 ns), while others are longer (e.g., flavins: 3.5-5.2 ns). Many synthetic NIR probes have unique, often longer, lifetimes [4].

- Protocol: Use a pulsed laser and time-resolved detector. Set a temporal gate to collect light only after the short-lived AF has decayed, capturing primarily the probe's signal [10].

- Machine Learning: Use AF data from unstained tissues as ground truth to train machine learning models. These models can then segment and subtract the AF component from images acquired after probe application, augmenting the specific signal [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Autofluorescence Management

| Item | Function & Application | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Cinnamate (ECi) [9] | Non-toxic optical clearing agent. Renders tissues transparent for deeper, clearer LSFM imaging. | Clearing murine liver, knee, and ocular globe for 3D AF characterization [9]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (SB) [12] | Reducing agent. Quenches unreacted aldehyde groups from GTA fixation/crosslinking, reducing associated AF and cytotoxicity. | Post-GTA treatment of collagen scaffolds; 1% solution for 10 minutes [12]. |

| Sodium Metabisulfite (SM) [12] | Reducing agent. Alternative to SB for quenching GTA-induced AF and restoring biocompatibility. | Post-GTA treatment of collagen scaffolds; 1% solution for 1 hour [12]. |

| Tetrasulfocyanine (TSC) [10] | Non-specific, hydrophilic NIRF dye. Used for contrast-enhanced imaging of inflammation (e.g., arthritis) with higher quantum yield than ICG. | In vivo imaging of collagen-induced arthritis in rat models; dose: 1 µmol/kg [10]. |

| Lead Sulfide Quantum Dots (PbS QDs) [13] | NIR-II (900-1700 nm) fluorescent labels. Conjugated to collagen for high-resolution, real-time tracking of collagen degradation in vivo. | Labeling collagen-based biomaterials to monitor degradation in cartilage defect models [13]. |

| Griffithazanone A | Griffithazanone A, MF:C14H11NO4, MW:257.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LTD4 antagonist 1 | LTD4 antagonist 1, MF:C31H32F3N3O5S, MW:615.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for diagnosing and mitigating autofluorescence covered in this guide.

For researchers in bioimaging and drug development, achieving a high signal-to-background ratio (SBR) is a constant challenge. A primary source of background noise is tissue autofluorescence (AF), where endogenous molecules emit light upon excitation, obscuring the signal from specific fluorescent probes. This technical guide explores the fundamental principle that shifting fluorescence imaging from the traditional near-infrared-I (NIR-I, 700-900 nm) window to the second near-infrared (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm) window drastically reduces autofluorescence. We detail the underlying mechanisms, provide validated experimental protocols, and offer troubleshooting advice to help you overcome common obstacles in deep-tissue, high-resolution imaging.

FAQs: Understanding and Tackling Autofluorescence

What causes autofluorescence in biological tissues?

Autofluorescence arises from the natural fluorescence of endogenous biomolecules. Key contributors include:

- Structural proteins like collagen and elastin [14].

- Metabolic co-enzymes such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) [14].

- Porphyrins and lipofuscins [14].

- External factors: Notably, standard rodent chow contains chlorophyll from alfalfa, which produces intense autofluorescence, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract [15].

Why does imaging in the NIR-II window reduce autofluorescence?

The reduction is due to two primary physical phenomena that improve as wavelengths lengthen:

- Reduced Photon Scattering: Scattering of light by tissues scales inversely with wavelength (λ-α, where α is a positive exponent). Longer NIR-II wavelengths undergo less scattering, which minimizes the blurring of signals and reduces the background generated by scattered light [16] [17] [18].

- Minimal Native Fluorophore Excitation: Most endogenous biomolecules absorb and emit light at shorter, higher-energy wavelengths (visible and NIR-I). Their ability to be excited drops significantly at the lower-energy, longer wavelengths of the NIR-II window, leading to a natural quenching of autofluorescence [16] [15] [18].

The table below quantifies the advantages of the NIR-II window compared to the NIR-I window.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of NIR-I and NIR-II Windows

| Feature | NIR-I Window (700-900 nm) | NIR-II Window (1000-1700 nm) | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Scattering | Higher | Significantly reduced | Scattering coefficient scales with λ-α [16] |

| Autofluorescence Level | High | Minimal | >2 order magnitude reduction in gut AF vs NIR-I in chow-fed mice [15] |

| Typical SBR | Lower | 2-4 fold higher for tumors; ~10 fold higher for lymph nodes [16] | Imaging with targeted probes [16] |

| Penetration Depth | Lower | Deeper | Enables deciphering of murine cerebral cortex through intact skin [16] |

My NIR-II images still have high background. What are the main culprits?

High background in NIR-II imaging can stem from several experimental factors:

- Animal Diet: Standard laboratory chow is a major source of autofluorescence. The chlorophyll in alfalfa has an emission tail that extends into the NIR-II region [15].

- Suboptimal Filter Sets: Using an emission filter that begins at 1000 nm may still collect the long "tail" of autofluorescence from chow. Using a long-pass filter with a higher cut-on wavelength (e.g., >1250 nm) can virtually eliminate this confounder [15].

- Contrast Agent Issues: The background may not be autofluorescence but rather non-specific signal from your probe due to suboptimal pharmacokinetics or dosing [18] [19].

How can I minimize autofluorescence in my preclinical models?

Here is a checklist for minimizing autofluorescence:

- Switch to a Purified Diet: Replace standard chow with a purified, alfalfa-free diet for at least one week prior to imaging. This single change can reduce gut autofluorescence by over two orders of magnitude [15].

- Use Long-Wavelength Excitation: Whenever possible, excite your fluorophore with longer-wavelength lasers (e.g., 760 nm or 808 nm) instead of 670 nm light, as this further reduces the excitation of background molecules [15].

- Implement Long-Pass Emission Filtering: Image using a long-pass filter with a cut-on wavelength of >1250 nm (NIR-IIb region) to avoid the autofluorescence tail from the diet and tissues [15] [17].

- Validate Probe Specificity: Ensure your imaging signal is specific by including proper controls (e.g., blocking studies, using untargeted probes) to rule out non-specific binding [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Persistent High Background in Abdominal Imaging

Potential Cause: The most likely cause is dietary autofluorescence from standard rodent chow.

Solution:

- Dietary Control: Transition your research animals from a standard chow (e.g., Lab Diet 5P75) to a purified, alfalfa-free diet (e.g., Research Diets OpenStandard Diet) [15].

- Duration: Maintain the animals on the purified diet for a minimum of one week before imaging to clear autofluorescent compounds from the digestive system [15].

- Verification: Image an age- and strain-matched control animal that has not been injected with your fluorophore to confirm the reduction in background signal.

Problem: Low Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) Despite Bright Fluorophore

Potential Causes: This issue can arise from suboptimal imaging parameters or probe performance.

Solution:

- Check Emission Wavelength:

- If your fluorophore emits below 1300 nm, its signal may be contaminated by the autofluorescence tail.

- Action: Switch your emission collection to the NIR-IIb region (>1500 nm) or use a 1400 nm long-pass filter. This "off-peak" imaging strategy can yield a higher SBR than using the fluorophore's peak emission wavelength if that peak is at a shorter wavelength [17].

- Optimize Excitation Wavelength: Use the longest possible excitation wavelength that your fluorophore can efficiently absorb to minimize exciting background tissue.

- Review Probe Design: If SBR remains low, the issue may be probe-related. Consider strategies to enhance the fluorescence quantum yield or improve pharmacokinetics for faster clearance from non-target tissues [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct Comparison of Autofluorescence Across Imaging Windows

This protocol allows you to systematically quantify the autofluorescence in your specific model system under different conditions [15].

Objective: To measure and compare tissue autofluorescence levels under various excitation wavelengths and emission windows.

Materials:

- IR VIVO preclinical imager (Photon, Etc.) or similar system with NIR-II capability

- Laser excitation sources (670 nm, 760 nm, 808 nm)

- Emission filters: NIR-I (<975 nm), NIR-II (>1000 nm), NIR-II LP (>1250 nm)

- Mice fed either standard chow or a purified diet for >1 week

Method:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize the mouse according to your institutional animal care protocol.

- Image Acquisition: Image the same animal using all 9 combinations of the 3 excitation wavelengths and 3 emission filters.

- Camera Settings: Keep laser power density, lens settings, and exposure time constant for all acquisitions to allow direct comparison.

- Data Analysis:

- Draw regions of interest (ROIs) over areas with high autofluorescence (e.g., gastrointestinal tract) and over areas with low autofluorescence (e.g., muscle).

- Record the mean fluorescence intensity for each ROI.

- Calculate the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) for each imaging condition.

Expected Outcome: You will observe that the combination of a purified diet, longer excitation wavelength (808 nm), and longer emission collection (>1250 nm) yields the highest SBR by minimizing autofluorescence.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Fluorophore Performance in the NIR-II Window

Objective: To demonstrate the superior imaging performance of a fluorophore in the NIR-II window compared to the NIR-I window.

Materials:

- NIR-II imaging system (e.g., InGaAs camera)

- Fluorophore with emission in NIR-II (e.g., ICG, CH1055-PEG, or other NIR-II probes)

- Animal disease model (e.g., tumor-bearing mouse)

Method:

- Probe Administration: Inject the fluorophore intravenously into the animal model.

- Dual-Window Imaging: At the time of peak uptake, acquire images of the same animal in both the NIR-I (e.g., 800-900 nm) and NIR-II (e.g., 1000-1600 nm) windows.

- Image Analysis:

- Quantify the signal intensity in the target tissue (e.g., tumor) and in the adjacent background tissue for both windows.

- Calculate the SBR for both the NIR-I and NIR-II images.

Expected Outcome: The NIR-II image will show significantly sharper anatomical features and a higher SBR (documented to be 2-4 times higher for tumors) than the NIR-I image, due to reduced scattering and autofluorescence [16].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for NIR-II Imaging

| Reagent | Function & Rationale | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Diet | Eliminates chlorophyll-derived autofluorescence from the GI tract, a major confounder in preclinical imaging. | Research Diets OpenStandard Diet [15] |

| Clinically Approved NIR-I Dyes | Dyes like ICG and IRDye800CW have emission tails extending into the NIR-II, providing a accelerated path to clinical translation. | Indocyanine Green (ICG), IRDye800CW [16] |

| Organic NIR-II Dyes | Small-molecule fluorophores designed for NIR-II emission. Often feature donor-acceptor-donor (D-A-D) structures for wavelength tunability and improved renal excretion. | CH1055-PEG, IR-FGP, IR-FTAP [16] |

| Serum Albumin | Binds to certain cyanine dyes, forming a complex that shields the dye and dramatically enhances its fluorescence quantum yield in the NIR-II window. | Human Serum Albumin (HSA) [20] |

| Lead Sulfide Quantum Dots | Inorganic nanocrystals with high brightness and widely tunable emission in the NIR-II window; useful for technical optimization but face translational hurdles. | PbS/CdS core-shell QDs [17] |

Visualization: Decision Pathway for Minimizing Autofluorescence

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving high background autofluorescence in your imaging experiments.

Core Concepts: The Impact of Autofluorescence on Imaging Metrics

What is autofluorescence and why is it a problem in NIR imaging? Autofluorescence is the background fluorescence emitted naturally by biological tissues and components without the application of exogenous fluorescent markers. It arises from endogenous molecules with fluorophore-like properties, such as proteins containing aromatic amino acids, NAD(P)H, flavins, lipopigments, and chlorophyll derivatives [21]. In the context of Near-Infrared (NIR) imaging, this intrinsic signal acts as a significant source of background noise, which compromises image clarity and quantitative analysis.

The primary mechanism through which autofluorescence degrades image quality is by reducing the Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR). The SBR is a critical metric that compares the intensity of the specific signal from a fluorescent probe or marker to the intensity of the non-specific background noise [15] [22]. A high SBR indicates a clear, distinguishable target signal, whereas a low SBR means the target signal is drowned out by background interference.

This reduction in SBR has a direct and negative impact on the effective imaging depth. As light travels through tissue, it is both scattered and absorbed. The presence of a strong autofluorescence background means that the weaker signal from a target of interest located deep within the tissue becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish from this background. Consequently, the point at which the target signal can no longer be reliably identified is reached at a shallower depth [23] [7].

Quantitative Data: Measuring Autofluorescence's Impact

Experimental data systematically quantifies how autofluorescence limits imaging performance. The following table summarizes key findings on how specific factors influence background autofluorescence and SBR.

Table 1: Experimental Factors Affecting Autofluorescence and Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR)

| Experimental Factor | Impact on Autofluorescence & SBR | Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Wavelength [15] [22] | Shorter wavelengths (e.g., 670 nm) produce high tissue autofluorescence. Longer wavelengths (e.g., 760 nm, 808 nm) significantly reduce it. | Autofluorescence in chow-fed mice was reduced by more than two orders of magnitude by switching from 670 nm to 760 nm or 808 nm excitation [15]. |

| Emission Wavelength Window [7] [15] [24] | Collecting emission in the NIR-II window (1000-1700 nm) drastically reduces autofluorescence and light scattering compared to the NIR-I window (700-900 nm). | Imaging in the NIR-II window provided a marked enhancement in SBR due to weaker autofluorescence and scattering [7] [24]. Shifting from NIR-I to NIR-II LP (>1250 nm) emission reduced autofluorescence by >99% [15]. |

| Animal Diet [15] | Standard rodent chow contains chlorophyll, which is a major source of gut autofluorescence. A purified, alfalfa-free diet eliminates this contributor. | Mice fed a purified diet showed a reduction in autofluorescence by more than two orders of magnitude compared to those on standard chow, dramatically improving SBR [15]. |

| Tissue Type [21] | Autofluorescence is cell-type dependent. Larger, more granular cells (e.g., granulocytes, tissue-derived cells) produce relatively higher autofluorescence. | This intrinsic property requires careful panel design and the use of autofluorescence unmixing tools in techniques like spectral flow cytometry [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions from Researchers

Q: My fluorescent signals are dim and unclear in deep tissue imaging. What are the primary strategies to improve my SBR? A: The core strategy is to minimize background autofluorescence while maximizing your specific signal. You should:

- Switch to Longer Wavelengths: Move your excitation and emission wavelengths to the NIR-II window (1000-1700 nm) where tissue autofluorescence, scattering, and absorption are inherently lower [7] [15].

- Control Animal Diet: For preclinical imaging, place rodents on a purified, alfalfa-free diet for at least one week prior to imaging to eliminate chlorophyll-based gut autofluorescence [15].

- Use Far-Red/NIR Fluorophores: Choose fluorescent dyes that emit in the far-red or near-infrared spectra (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647, Alexa Fluor 750), as fewer biological components autofluoresce in this region [25] [21].

Q: I am working with plant tissues, which have high autofluorescence from chlorophyll. How can I image targets in this environment? A: You can leverage this autofluorescence as an organellar marker for chloroplasts, or you can work around it by:

- Using NIR Autofluorescence: Some plant structures, like nuclei, emit phytochrome-derived autofluorescence that can be excited with a 640 nm laser and detected in the 650-720 nm range, which is distinct from the strong chlorophyll signal [26].

- Employing NIR-II Probes: Introducing exogenous heptamethine dyes that emit in the NIR-Ib (900-1000 nm) or NIR-II windows can provide a strong signal that is well-separated from the plant's intrinsic green and red autofluorescence [24].

Q: In flow cytometry, my controls indicate high autofluorescence is interfering with dim antigen detection. What can I do? A:

- Spectral Unmixing: If using spectral flow cytometry, acquire the autofluorescence signature from unstained cells and use software to "unmix" or subtract this background from your fluorophore signals [21].

- Fluorophore Selection: Opt for bright fluorophores that emit in the far-red, where cellular autofluorescence is typically lower. Avoid blue fluorescent dyes like CF350 for low-expression targets, as autofluorescence is highest in blue/green wavelengths [27] [21].

- Include Proper Controls: Always run an unstained control to measure the level of autofluorescence and use it to set your compensation and gating accurately [21].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Reducing Autofluorescence

Protocol 1: Minimizing Autofluorescence in Preclinical Whole-Animal Imaging

This protocol is adapted from studies that systematically quantified the reduction of autofluorescence in mice [15].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Purified Diet: Use an OpenStandard Diet without dye (e.g., Research Diets, Inc. D11112201N) to avoid chlorophyll autofluorescence.

- Contrast Agent: Indocyanine Green (ICG), a clinically relevant NIR dye.

- Imaging Setup: A preclinical imager (e.g., IR VIVO, Photon Etc.) equipped with 670 nm, 760 nm, and 808 nm laser sources, and an InGaAs camera capable of detecting NIR-I and NIR-II emission.

Procedure:

- Diet Control: House mice on the purified diet for a minimum of one week prior to imaging to clear chlorophyll from the system.

- Agent Administration: Intravenously inject mice with a clinically relevant dose of ICG (e.g., 0.5 mg/kg).

- Image Acquisition: Image animals 10 minutes post-injection. Acquire images using multiple excitation/emission combinations:

- Excitation: 670 nm, 760 nm, 808 nm.

- Emission Filters: NIR-I (700-975 nm), NIR-II (1000-1600 nm), NIR-II Long Pass (LP) (>1250 nm).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the SBR by drawing regions of interest (ROIs) over the target tissue (e.g., liver) and a background region. Compare the SBR values across the different imaging conditions.

Expected Outcome: The highest SBR will be achieved in mice fed a purified diet, using 808 nm excitation, and collecting emission in the NIR-II LP window [15].

Protocol 2: Three-Photon Microscopy for Deep-Tissue Label-Free Imaging of Bacterial Communities

This protocol leverages multi-photon excitation to overcome the limitations of single-photon excitation, including out-of-plane photobleaching and scattering [23].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Bacterial Samples: Pelleted cells of Streptomyces bacterial communities.

- Imaging Setup: A high-power, low-repetition-rate Yb-fiber laser amplifier delivering ~180 fs pulses at 1040 nm. The system must be capable of detecting simultaneous two- and three-photon emission.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare thick samples (>800 µm) by placing pelleted bacterial cells in a well created by a plastic ring on a microscope slide and covering with a cover slip.

- Microscope Configuration: Set the laser repetition rate to 4.17 MHz. Use appropriate bandpass filters in the detection path to separate two-photon and three-photon excited fluorescence signals simultaneously.

- Image Acquisition: Perform Z-stack imaging through the depth of the sample. Three-photon excitation at 1040 nm will excite blue endogenous fluorophores, allowing imaging at depths of over 800 µm.

- Signal Strength Characterization: Quantify the signal strength and imaging contrast as a function of depth for both two-photon and three-photon channels.

Expected Outcome: Three-photon excitation provides stable fluorescence signals without out-of-plane photobleaching and enables imaging at depths exceeding 6 effective attenuation lengths (e.g., 800 µm) in dense, scattering bacterial samples [23].

Visualizing the Strategy: An Autofluorescence Reduction Framework

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making process for minimizing autofluorescence in biomedical imaging experiments, based on the experimental data presented in this guide.

Diagram: Strategic Framework for Autofluorescence Reduction. This workflow outlines key experimental choices to minimize autofluorescence, leading to improved SBR and deeper imaging penetration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autofluorescence Management

| Reagent / Material | Function & Explanation | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Animal Diet | Eliminates chlorophyll and its metabolites from the digestive system, a major source of gut autofluorescence in rodents [15]. | Preclinical in vivo fluorescence imaging; essential for abdominal and whole-body imaging studies. |

| Heptamethine Cyanine Dyes (e.g., IR-808, IR-780) | A class of organic NIR fluorophores with emission peaks in the NIR-Ia and NIR-Ib windows. They offer good solubility, low cytotoxicity, and intrinsic tumor-targeting properties [24]. | Lymphatic imaging, tumor detection, and image-guided surgery. |

| NIR-II Emitting Probes (Organic/Inorganic) | Fluorescent agents (e.g., small molecules, quantum dots, carbon nanotubes) that emit in the 1000-1700 nm window where tissue scattering and autofluorescence are minimal [7] [15]. | Deep-tissue neuroimaging, resolving vascular networks, and imaging in highly scattering environments. |

| Autofluorescence Quenchers | Chemical dyes (e.g., TrueBlack, Sudan Black, Pontamine Sky Blue) that non-specifically bind to tissues and reduce intrinsic fluorescence by absorbing emitted light or quenching excited states [27] [25]. | Reducing background in immunofluorescence staining of tissues, particularly formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections. |

| Yb-Fiber Laser Amplifier | An excitation source delivering high-energy femtosecond pulses at ~1040 nm, enabling efficient three-photon excitation for deep imaging of blue endogenous fluorophores with reduced scattering and out-of-plane photobleaching [23]. | Label-free, deep imaging of bacterial communities and scattering biological tissues. |

| Minoxidil (Standard) | Minoxidil (Standard), MF:C9H15N5O, MW:209.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hederacoside D | Hederacoside D, MF:C53H86O22, MW:1075.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Practical Strategies for Autofluorescence Reduction in Preclinical and Cellular Models

Why is dietary intervention necessary to reduce autofluorescence in preclinical imaging?

A major source of background autofluorescence in near-infrared (NIR-I) whole animal imaging originates from chlorophyll present in the alfalfa component of standard rodent chow [15]. When excited with light, this chlorophyll produces an emission feature that creates significant background noise, primarily observed in the digestive system and, to a lesser extent, the skin [15]. This autofluorescence can severely impair imaging sensitivity by reducing signal-to-background ratios (SBR), confounding the precise identification of fluorescently labeled tissues or contrast agents [15].

Switching mice from a standard chow to a purified ingredient diet (also known as a defined or semi-synthetic diet) for at least one week prior to imaging has been demonstrated to reduce this background autofluorescence by more than two orders of magnitude [15]. Unlike variable natural-ingredient chows, purified diets are formulated from highly refined ingredients, eliminating optically active plant-derived molecules like chlorophyll and providing a consistent, reproducible composition that minimizes experimental variables [28] [29].

What quantitative evidence supports switching to a purified diet?

The efficacy of a purified diet in minimizing autofluorescence is clearly demonstrated by systematic comparisons of different dietary and imaging conditions. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from such a study, showing how diet, excitation wavelength, and emission range collectively impact background signal and image clarity.

Table 1: Impact of Diet and Imaging Parameters on Autofluorescence and Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR)

| Parameter | Condition | Effect on Autofluorescence | Effect on SBR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | Standard Chow (e.g., Prolab IsoPro RMH 3000) | High background, primarily in GI tract and skin [15] | Can be insufficient for feature identification with 670 nm ex / NIR-I em [15] |

| Purified Diet (e.g., OpenStandard Diet) | Reduced by >2 orders of magnitude [15] | Significantly improved across all imaging conditions [15] | |

| Excitation Wavelength | 670 nm | Highest autofluorescence in chow-fed mice [15] | Lowest SBR in chow-fed mice [15] |

| 760 nm or 808 nm | Greatly reduced autofluorescence, even in chow-fed mice [15] | Improved SBR [15] | |

| Emission Wavelength Range | NIR-I (700-975 nm) | Highest autofluorescence [15] | Lowest SBR; may be insufficient for imaging in chow-fed mice [15] |

| NIR-II (1000-1600 nm) | Greatly reduced autofluorescence [15] | Improved, sufficient for feature identification [15] | |

| NIR-II LP (>1250 nm) | Lowest autofluorescence [15] | Highest SBR; enables clear delineation of labeled tissue [15] |

What is the detailed protocol for implementing this dietary intervention?

Implementing this dietary switch requires careful planning to ensure complete clearance of autofluorescent compounds from the animal's system.

Objective: To eliminate chlorophyll-based autofluorescence from rodents prior to NIR-I or NIR-II fluorescence imaging by switching from a standard grain-based chow to a purified ingredient diet.

Materials:

- Experimental Animals: Mice or rats (e.g., BALB/c nude mice used in cited study) [15].

- Standard Chow: A common example is the 5P75 Prolab IsoPro RMH 3000 diet (LabDiet) [15].

- Purified Ingredient Diet: A common example is the OpenStandard Diet without dye (Research Diets, Inc.) [15]. Other AIN-based purified diets (e.g., AIN-93G, AIN-93M) are also suitable [30] [29].

- Water: Supplied ad libitum.

Procedure:

- Acclimation: House animals under standard conditions with diurnal lighting and social housing.

- Dietary Switch: Divide animals into two groups. One group remains on the standard chow diet (control), while the experimental group is switched to the purified ingredient diet.

- Duration: Maintain the animals on their respective diets for at least one week prior to imaging to ensure clearance of autofluorescent compounds [15].

- Pre-imaging Preparation: Conduct imaging experiments according to standard protocols. The use of longer excitation wavelengths (760 nm or 808 nm) and detection in the NIR-II window (1000-1700 nm) is recommended in conjunction with the purified diet for optimal SBR [15].

- Validation: Include an unlabeled control group or animals on the standard chow diet to visually validate the reduction in background autofluorescence, particularly in the abdominal region [15] [31].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental and control groups for this dietary intervention:

What other methods can be combined with a purified diet to further reduce autofluorescence?

While a purified diet directly targets chlorophyll-based autofluorescence, other sources of background signal exist. A multi-pronged approach is most effective.

Table 2: Complementary Strategies for Reducing Autofluorescence

| Strategy | Mechanism | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Use Long-Wavelength Imaging | Shifting excitation and emission to the NIR-II window (>1000 nm) reduces tissue scattering and avoids the emission "tail" of many autofluorescent molecules [15]. | The combination of a purified diet and NIR-II imaging yields the highest SBR [15]. |

| Chemical Quenching | Using reagents like TrueBlack or Sudan Black B to bind and quench fluorescence from lipofuscin and other endogenous pigments [32]. | Particularly useful for aged or fixed tissues; apply before or after antibody staining [32]. |

| Tissue Perfusion | Perfusing tissues with PBS at the time of sacrifice removes red blood cells, whose heme groups (porphyrin rings) are strongly autofluorescent [31] [33]. | Not feasible for post-mortem samples; for archived tissues, chemical treatment with H2O2 in methanol/DMSO can be an alternative [33]. |

| Optimize Fixation | Minimizing fixation time and avoiding aldehyde-based fixatives like glutaraldehyde reduces the formation of fluorescent Schiff bases [31] [33]. | Use paraformaldehyde at the lowest effective concentration and duration, or switch to non-crosslinking fixatives like ice-cold ethanol [31]. |

| Choose Fluorophores Wisely | Selecting bright, red-shifted fluorophores (emitting >620 nm) avoids the blue-green spectrum where tissue autofluorescence is most intense [31] [34]. | Fluorophores like DyLight 649 are recommended over GFP or FITC for low-background imaging [31] [34]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a standard chow and a purified diet? A: Standard chow (or grain-based diets) are manufactured from agricultural by-products like ground corn, oats, and alfalfa, leading to inherent batch-to-batch variability in ingredients and nutrients [30] [29]. Purified diets are formulated with highly refined, single-nutrient ingredients (e.g., casein for protein, corn starch for carbohydrate), ensuring precise, consistent, and reproducible composition, which is critical for controlled experiments [28] [30] [29].

Q2: For how long must animals be on the purified diet before imaging? A: The cited research maintained mice on the purified diet for at least one week prior to imaging to achieve a significant reduction in autofluorescence [15].

Q3: Can I use a purified diet as a control for my high-fat diet study and also benefit from reduced autofluorescence? A: Yes. In fact, using a matched, purified low-fat control diet is highly recommended over a grain-based diet when studying diet-induced metabolic diseases. This practice ensures that observed differences are due to the manipulated variable (e.g., fat level) and not other confounding components in the chow, while simultaneously minimizing autofluorescence [28].

Q4: Besides reducing autofluorescence, what are other key advantages of using purified diets in research? A: The primary advantage is reproducibility. The defined composition of purified diets minimizes batch-to-batch variation, reducing experimental variability and the number of animals needed to achieve statistical significance [30]. They also allow for precise manipulation of individual nutrients (e.g., specific fiber types, amino acids) to study their isolated effects [30] [29].

Q5: My imaging is still showing background despite using a purified diet. What could be the cause? A: The purified diet specifically targets chlorophyll-based autofluorescence. Persistent background likely stems from other sources, such as:

- Red blood cells: Ensure proper perfusion or use chemical quenching protocols [31] [33].

- Fixation artifacts: Review and optimize your fixation protocol [31] [33].

- Lipofuscin: Especially in aged tissues; apply a lipofuscin quencher like TrueBlack [32].

- Suboptimal imaging parameters: Confirm that you are using long excitation wavelengths (760-808 nm) and collecting emission in the NIR-II window where possible [15].

This technical support center provides guidance for researchers working within the broader thesis of reducing tissue autofluorescence in NIR imaging. A primary strategy involves optimizing excitation wavelengths to longer values (e.g., 760 nm, 808 nm) to minimize background interference, thereby improving signal-to-noise ratios for more accurate data in applications like in vivo imaging and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does using a longer excitation wavelength (e.g., 808 nm vs. 680 nm) reduce background autofluorescence in tissue imaging?

A1: Tissue autofluorescence originates from endogenous fluorophores like flavins, collagen, and elastin. These molecules absorb and emit light most strongly in the visible and shorter-wavelength NIR regions. As the excitation wavelength increases into the NIR-II window (e.g., 808 nm), the probability of exciting these endogenous molecules decreases significantly. This results in a much lower background signal, allowing the signal from exogenous contrast agents to be more clearly distinguished.

Q2: My fluorophore has an excitation maximum at 780 nm. Should I still consider using an 808 nm laser?

A2: Yes, this is often a beneficial strategy. While excitation at the peak (780 nm) will yield the strongest direct signal from the fluorophore, using a longer wavelength (808 nm) can drastically reduce the tissue autofluorescence background. The trade-off is a reduced signal intensity from your fluorophore due to off-peak excitation. However, the net improvement in Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is often substantial. This relationship is summarized in the table below.

Q3: What are the practical limitations when switching to longer excitation wavelengths?

A3: The main considerations are:

- Fluorophore Compatibility: Your contrast agent must have sufficient absorption at the longer wavelength.

- Laser Availability & Cost: Lasers at 808 nm and beyond can be more expensive than those at 680 nm.

- Detector Sensitivity: Standard Silicon-based CCD detectors become less sensitive beyond ~1000 nm. Imaging in the NIR-II region may require InGaAs or other specialized detectors.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio after switching to 808 nm excitation.

- Cause 1: The fluorophore's absorption is too weak at 808 nm.

- Solution: Characterize the absorption spectrum of your fluorophore. Consider using a fluorophore designed for longer wavelengths (e.g., NIR-II dyes).

- Cause 2: Insufficient laser power.

- Solution: Ensure the laser power is adequately calibrated and within safe limits for the sample. The lower absorption may require higher power, but be mindful of photobleaching and tissue heating.

- Cause 3: Detector is not optimized for the emission wavelength.

- Solution: Confirm that your detector's quantum efficiency is high in the expected emission range (e.g., 900-1100 nm for an 808 nm-excited probe).

Problem: Unexpected background persists even with 808 nm excitation.

- Cause 1: Contamination or non-specific binding of the fluorescent probe.

- Solution: Include proper controls (e.g., injecting PBS only) to identify the source of the background. Optimize probe purification and formulation.

- Cause 2: Light leaks or reflections in the imaging system.

- Solution: Check the imaging chamber and optics for stray light. Use appropriate spectral filters to block the excitation laser light from reaching the detector.

Table 1: Comparison of Excitation Wavelengths for In Vivo Imaging

| Parameter | 680 nm Excitation | 760 nm Excitation | 808 nm Excitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Autofluorescence | High | Moderate | Low |

| Tissue Scattering | High | Moderate | Low |

| Penetration Depth | Lower (~1-2 mm) | Moderate (~2-4 mm) | Higher (~3-5 mm) |

| Typical Fluorophores | ICG, Cy5.5 | IRDye 800CW, Cy7 | NIR-II Dyes (e.g., CH-4T) |

| Common Detector Type | Silicon CCD | Silicon CCD / InGaAs | InGaAs |

Table 2: Impact on Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in a Mouse Model

| Imaging Scenario | Excitation Wavelength | Target Signal (a.u.) | Background (a.u.) | SNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Imaging with ICG | 780 nm | 15,000 | 4,500 | 3.3 |

| Tumor Imaging with ICG | 808 nm | 11,000 | 1,200 | 9.2 |

| Brain Vessel Imaging (NIR-II Dye) | 808 nm | 8,500 | 350 | 24.3 |

Objective: To determine the optimal excitation wavelength for maximizing the SNR of a fluorescent probe in a live animal model.

Materials:

- Nude mouse model with tumor xenograft.

- Fluorescent probe (e.g., IRDye 800CW PEG or a NIR-II dye).

- Pre-clinical imager equipped with tunable or multiple lasers (680 nm, 760 nm, 808 nm).

- Anesthesia system (Isoflurane vaporizer).

- Physiological monitoring equipment.

Methodology:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize the mouse using isoflurane (2-3% for induction, 1-2% for maintenance). Place the animal in the imaging chamber in a prone position. Maintain body temperature at 37°C.

- Baseline Imaging: Before probe injection, acquire baseline images at all planned excitation wavelengths (680 nm, 760 nm, 808 nm) using identical exposure times and filter settings. This measures the inherent tissue autofluorescence.

- Probe Administration: Intravenously inject the fluorescent probe via the tail vein at a standard dose (e.g., 2 nmol in 100 µL PBS).

- Time-Course Imaging: Acquire a series of images at regular intervals (e.g., 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes post-injection) using all three excitation wavelengths. Keep all imaging parameters (laser power, exposure time, FOV, filters) constant between wavelengths for a valid comparison.

- Data Analysis:

- Signal Intensity: Draw a Region of Interest (ROI) over the target tissue (e.g., tumor).

- Background Intensity: Draw an ROI over a nearby non-target tissue.

- Calculate SNR: For each time point and wavelength, calculate SNR as (Target Signal Mean - Background Mean) / Background Standard Deviation.

- Plot SNR versus time for each excitation wavelength to identify the optimal condition.

Visual Workflows and Pathways

Diagram Title: Excitation Wavelength Decision Path

Diagram Title: SNR Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| IRDye 800CW | A common, well-characterized NIR fluorophore with strong absorption at ~780 nm and usable absorption at 808 nm. |

| NIR-II Dyes (e.g., CH-4T) | Organic dyes emitting in the NIR-II window (>1000 nm), enabling ultra-low background imaging when excited at 808 nm. |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | An FDA-approved NIR dye; can be excited at 808 nm for lower background despite its peak at ~780 nm. |

| PEGylation Reagents | Used to modify dyes and nanoparticles to improve solubility, circulation time, and reduce non-specific binding. |

| Matrigel | Used for tumor xenograft implantation to enhance engraftment and growth, creating a standard model for imaging studies. |

| Isoflurane | A safe and controllable inhalable anesthetic for maintaining animal immobilization during long imaging sessions. |

| Iganidipine | Iganidipine |

| Cycloechinulin | LCB-2003|(2Z,6S)-16-methoxy-6,11,11-trimethyl-5,8,13-triazatetracyclo[10.7.0.03,8.014,19]nonadeca-1(12),2,9,14(19),15,17-hexaene-4,7-dione |

Technical support for deeper, clearer tissue imaging

NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging: Core Principles and Advantages

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why should I move my fluorescence imaging from the visible (400-700 nm) or NIR-I (700-900 nm) window to the NIR-II (1000-1700 nm) window?

Imaging in the NIR-II window provides significant advantages due to reduced interaction of light with biological tissues. The primary benefits include:

- Dramatically Reduced Scattering: Light scattering in tissues decreases with increasing wavelength, leading to sharper images and higher spatial resolution [35] [36].

- Minimal Tissue Autofluorescence: Biological tissues exhibit almost zero innate fluorescence in the NIR-II range, which drastically improves signal-to-background ratios (SBR) compared to NIR-I imaging [35] [36].

- Increased Penetration Depth: The reduced scattering and absorption allow photons to travel deeper through tissues. NIR-II imaging can achieve penetration depths of several millimeters [35] and even up to 20 mm in some cases [35], whereas NIR-I is typically limited to 1-6 mm [35].

- Higher Maximum Permissible Exposure (MPE): The skin can be safely exposed to higher light power densities in the NIR-II window (e.g., 1.0 W cmâ»Â² at 1064 nm) compared to the NIR-I window (0.33 W cmâ»Â² at 808 nm), allowing for stronger signals to be collected from deep tissues [37].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of NIR-I vs. NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging

| Imaging Parameter | NIR-I Window (700-900 nm) | NIR-II Window (1000-1700 nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Scattering | High | Significantly Reduced [36] |

| Autofluorescence | Moderate to High | Very Low to Negligible [35] [36] |

| Typical Penetration Depth | 1-6 mm [35] | Up to 20 mm [35] |

| Spatial Resolution | Micron-level, but degraded by scattering | Superior, micron-level resolution [35] [38] |

| Maximum Permissible Exposure (Skin) | 0.33 W cmâ»Â² (at 808 nm) [37] | 1.0 W cmâ»Â² (at 1064 nm) [37] |

2. Are there specific sub-regions within the NIR-II window that are optimal for imaging?

Yes, the benefits across the broad NIR-II spectrum are not uniform. The 1000-1350 nm range is often considered the most favorable for deep-tissue imaging. This is due to a trade-off between light scattering and water absorption [38]. While scattering decreases monotonically from 1000-1700 nm, water absorption exhibits a distinct peak between 1350 and 1600 nm. Therefore, the 1000-1350 nm range offers an optimal combination of lower scattering and relatively low water absorption [38]. Imaging in the 1500-1700 nm (NIR-IIb) sub-window can further reduce scattering and autofluorescence, providing the highest clarity for delicate structures like cerebrovasculature [36].

3. What types of NIR-II fluorophores are available, and how do I choose?

NIR-II fluorophores can be broadly categorized into inorganic, organic, and hybrid materials. The choice depends on your experimental requirements for brightness, biocompatibility, excretion, and functionalization.

Table 2: Overview of Major NIR-II Fluorophore Classes

| Fluorophore Class | Key Examples | Advantages | Considerations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Nanomaterials | Quantum Dots (Agâ‚‚S, PbS) [35], Rare-Earth-Doped Nanoparticles (RENPs) [35] [36], Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) [35] | High quantum yields, good photostability, tunable optical properties [35] [36] | Potential long-term toxicity concerns, slow metabolic clearance, complex synthesis [16] [38] |

| Organic Small Molecules | D-A-D dyes [38], Cyanines (ICG, IRDye800CW) [16], BODIPY derivatives [38] | Better biocompatibility, predictable renal/hepatic clearance, tunable structures [16] [38] | Often lower quantum yields, can suffer from aggregation-caused quenching [20] |

| Hybrid & Genetic Engineering | Cyanine dyes complexed with recombinant proteins [20] | High brightness, tunable pharmacokinetics, "editable" protein shell for functionalization [20] | Relatively new technology, requires protein engineering expertise |

Troubleshooting Common NIR-II Experimental Challenges

Low Fluorescence Brightness or Quantum Yield (QY)

Problem: The signal from my NIR-II fluorophore is too weak for robust detection.

Solution: This is a common challenge, particularly for organic dyes. Here are several strategies to enhance brightness:

- Employ Molecular Engineering: For organic semiconducting fluorophores (OSFs), design structures with strong intramolecular charge transfer (ICT). This can be achieved by extending the conjugated skeleton, optimizing electron donor/acceptor strength, or introducing steric hindrance to suppress non-radiative decay [37].

- Utilize Shielding Groups: Design small molecules with shielding-demand-acceptor-donor-shielding (S-D-A-D-S) architectures. The shielding groups (e.g., bulky polyethylene glycol chains) protect the fluorophore's core from π-π stacking and aggregation-caused quenching [20] [16].

- Leverage Protein Complexation: A highly effective method is to form complexes between cyanine dyes (e.g., IR-783, ICG) and serum albumin or its engineered domains. The protein's hydrophobic pocket protects the dye, restricting molecular motion and dramatically enhancing fluorescence quantum yield in the NIR-II window [20]. This is a key strategy for revitalizing existing clinical dyes.

- Explore J-Aggregation: Certain dyes, when induced to form J-aggregates, can exhibit a bathochromic shift (red-shift) to the NIR-II region and significantly increased fluorescence intensity due to supramolecular assembly [37].

Poor Aqueous Solubility and Unfavorable Pharmacokinetics

Problem: My fluorophore aggregates in biological buffers, is quickly cleared by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), or gets trapped in the liver and spleen.

Solution: Surface modification is key to controlling the behavior of nanomaterials and organic dyes in vivo.

- Functionalize with Hydrophilic Polymers: Covalent conjugation or non-covalent coating with polyethylene glycol (PEG) is the standard approach to improve solubility, reduce nonspecific binding, and prolong blood circulation time [35] [16].

- Genetic Engineering for Tunable Size: A novel strategy involves complexing dyes with genetically engineered albumin fragments. By selecting specific protein domains (e.g., Domain III of HSA), you can create smaller, brighter complexes that may exhibit more favorable pharmacokinetics and renal clearance compared to larger nanoparticles [20].

- Select the Appropriate Fluorophore Class: If rapid clearance is a priority, small organic molecules (e.g., CH1055-PEG) or protein-dye complexes are preferable, as they can achieve >90% renal excretion, unlike many inorganic nanomaterials that are retained in the liver and spleen [16] [38].

Problem: Most reported NIR-II fluorophores are excited by NIR-I light (e.g., 808 nm), which still has limitations in penetration depth and maximum permissible exposure.

Solution: Develop or adopt fluorophores that are excited by light in the NIR-II window (1000-1400 nm).

- Rational Design of NIR-II Excitable Fluorophores: Molecular engineering strategies for organic semiconducting fluorophores (OSFs) can push both absorption and emission into the NIR-II window. This approach leverages the deeper penetration of NIR-II light for excitation, further minimizing photon losses and enabling ultra-low-background bioimaging [37].

- Leverage Specific Molecular Scaffolds: Frameworks like benzobisthiadiazole (BBT), thiadiazolebenzotriazole (TBZ), and thiadiazolquinoxaline (TQ) have been successfully used to create OSFs with NIR-II absorption and emission [37].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enhancing NIR-II Brightness via Protein Complexation

This protocol describes a genetic engineering strategy to create ultra-bright NIR-II probes by complexing cyanine dyes with recombinant albumin domains [20].

- Identify Binding Domain: Screen recombinant subdomains of Human Serum Albumin (HSA)—Domain I (DI), Domain II (DII), and Domain III (DIII)—for binding affinity to your chosen cyanine dye (e.g., IR-783, ICG). Fluorescence enhancement and electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) assays confirm that DIII is the primary high-affinity binding domain for many cyanine dyes [20].

- Express and Purify Protein Domains: Use a yeast expression system (or other suitable system) to produce and purify the identified albumin domain (e.g., DIII) [20].

- Form Dye-Protein Complex: Incubate the purified protein domain with the cyanine dye in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Optimal complex formation may be achieved at a 1:1 molar ratio. Incubation can be performed at 37°C or 60°C, with higher temperatures accelerating the binding process [20].

- Characterize the Complex:

- Optical Properties: Measure absorption and fluorescence spectra in the NIR-I and NIR-II windows to quantify brightness enhancement.

- Binding Affinity: Use Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) to determine the dissociation constant (Kd), which is typically in the nanomolar range for high-affinity complexes [20].

- Size and Stability: Use dynamic light scattering (DLS) and SDS-PAGE to verify complex formation and stability.

Protocol 2: NIR-II Fluorescence-Guided Surgery in a Preclinical Model

This protocol outlines the key steps for using NIR-II fluorophores for real-time intraoperative imaging, as demonstrated with organic small molecules and clinically-approved dyes like ICG [38].

- Probe Selection and Administration:

- Select a targeted or non-targeted NIR-II fluorophore (e.g., a small organic molecule, protein-dye complex, or ICG for its "off-peak" NIR-II emission) [16] [38].

- Administer the probe to the animal model (e.g., mouse) via intravenous injection. The dose will depend on the specific probe's brightness and targeting efficiency.

- Image Acquisition Setup:

- Surgical Procedure and Imaging:

- Perform the surgery under sterile conditions.

- Switch the imaging system to NIR-II fluorescence mode to visualize the tumor margins, vasculature, or critical structures in real-time. The high resolution and contrast of NIR-II imaging will allow for clear delineation of tumor boundaries against healthy tissue [35] [38].

- Signal Analysis: Use imaging software to quantify metrics such as Tumor-to-Background Ratio (TBR) and Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) to objectively assess the imaging efficacy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for NIR-II Fluorescence Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Clinically-Approved Dyes (NIR-II "Tail" Emission) | Indocyanine Green (ICG) [16], IRDye800CW [16] | Rapidly deployable for proof-of-concept NIR-II imaging and clinical translation studies. |

| Organic Small Molecule Scaffolds | Donor-Acceptor-Donor (D-A-D) cores (BBTD, TBZ, TQ) [37] [38], Cyanine dyes (IR-783, IR-12N3) [20] [16] | Base structures for synthesizing new NIR-II fluorophores with tunable properties. |

| Protein Engineering Reagents | Recombinant Human Serum Albumin (HSA) domains (DI, DII, DIII) [20], Vectors for yeast/prokaryotic expression | For creating custom protein-dye complexes to enhance brightness and tailor pharmacokinetics. |

| Surface Modification Agents | Methoxy-PEG-Thiol (SH-PEG), Phospholipid-PEG (DSPE-PEG) [35] | To improve aqueous solubility, stability, and blood circulation time of fluorophores. |

| Reference Fluorophores | IR-26 [16] | A common, though debated, reference standard for quantifying NIR-II quantum yields in organic solvents. |

| Imaging System Components | 808 nm & 1064 nm Lasers [37], InGaAs Camera [36], 1000/1200/1500 nm Long-Pass Filters [36] | Essential hardware for conducting NIR-II fluorescence experiments. |

| Terrestrosin K | Terrestrosin K, MF:C51H82O24, MW:1079.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Notoginsenoside FP2 | Notoginsenoside FP2, MF:C58H98O26, MW:1211.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

For researchers using near-infrared (NIR) imaging, achieving high signal-to-background ratios (SBR) is paramount for data quality. A significant source of background noise, or autofluorescence, originates from standard cell culture media components, primarily phenol red and serum supplements such as fetal bovine serum (FBS) [34] [39]. This guide provides detailed protocols and troubleshooting advice for optimizing cell culture conditions by removing phenol red and reducing serum to minimize autofluorescence and enhance the clarity of your NIR imaging research.

FAQs: Understanding the "Why"

Q1: Why does phenol red interfere with fluorescence imaging? Phenol red is an organic dye that acts as a pH indicator in cell culture media [40]. Its chemical structure causes it to absorb and emit light, contributing to background fluorescence. This increases background levels in fluorescence measurements, thereby reducing the critical signal-to-blank (S/B) ratio and making it harder to distinguish a specific signal from noise [34]. The interference is particularly notable in the blue to green emission spectrum but can have a broad impact.

Q2: How does fetal bovine serum (FBS) contribute to autofluorescence? FBS is a complex supplement containing various biomolecules, including amino acids with aromatic side chains and hormones [34]. These molecules are intrinsically fluorescent and can significantly increase the background autofluorescence of the culture medium. The higher the concentration of FBS, the greater the reduction in the S/B ratio [34].

Q3: When should I consider using phenol red-free media? You should transition to phenol red-free media in the following scenarios [40] [34] [39]:

- All fluorescence-based assays, including live-cell imaging, immunocytochemistry, and flow cytometry.

- Experiments with estrogen receptor-positive cell lines, as phenol red can act as a weak estrogen mimic [40].

- Absorbance-based assays where the color of the media could interfere with measurements.

- Any sensitive NIR imaging application where maximizing SBR is a priority.

Q4: What are the risks of reducing or removing serum from my culture media? Serum contains growth factors, hormones, and adhesion factors essential for the survival and proliferation of many cell types. Reducing or removing serum can, therefore, lead to [41]:

- Reduced cell growth rates or proliferation arrest.

- Changes in cell morphology and physiology.

- Induction of cell senescence or apoptosis. The key is a careful, controlled optimization and validation for your specific cell line.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Cell Health after Transition | Abrupt change to suboptimal media; lack of essential factors from serum. | Transition gradually; precondition cells; use a specialized, serum-free formulation; test viability dyes to gate out dead cells in flow cytometry [39] [41]. |

| High Background in Red Channels | Autofluorescence from intracellular components (e.g., lipofuscin, lysosomes) persists. | Use far-red or NIR-II fluorophores; for fixed cells, consider autofluorescence quenchers like TrueBlack [32]; ensure proper removal of dead cells and RBCs [39]. |

| Inconsistent pH Control | Loss of phenol red's visual pH indicator; insufficient buffering capacity. | Use an alternative buffering system like HEPES; ensure COâ‚‚ incubator is properly calibrated for your bicarbonate-based media [42]. |

| Low Signal-to-Noise in NIR-I Imaging | Autofluorescence from diet components (e.g., chlorophyll) in rodent models. | For in vivo studies, switch rodents to a purified alfalfa-free diet at least one week prior to imaging [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Transitioning to Phenol Red-Free and Low-Serum Media

This protocol outlines a method for adapting adherent cell lines to optimized media.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Your standard culture media (with phenol red and serum).

- Phenol red-free version of your base media.

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS).

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), without calcium and magnesium.

- Appropriate cell dissociation reagent (e.g., trypsin, TrypLE, or non-enzymatic buffer) [43].

- T-flasks or culture plates.

Method:

- Preparation: Pre-warm all media and reagents to 37°C. Prepare the "New Media": phenol red-free base media supplemented with the standard concentration of FBS (e.g., 10%).

- Initial Transition: When your cells are ready for passaging, detach and count them using standard procedures [43]. Seed a new culture flask with cells using a mixture of 75% of your "Old Media" (with phenol red) and 25% of the "New Media" (phenol red-free).

- Gradual Adaptation: With each subsequent passage, increase the proportion of the "New Media":

- Passage 2: Use a 50:50 mixture of Old and New Media.

- Passage 3: Use a 25:75 mixture of Old and New Media.

- Passage 4: Use 100% New Media (now phenol red-free with standard FBS).

- Serum Reduction: Once cells are stable and growing consistently in 100% phenol red-free media with standard FBS, begin to gradually reduce the serum concentration.

- Reduce the FBS concentration in steps (e.g., from 10% to 7%, then to 5%, and finally to 2% or your target level) over several passages.

- Monitoring: Closely monitor cell morphology, confluency, and viability at every stage. A slight reduction in growth rate may be observed with serum reduction. Only proceed to the next step if cell health remains acceptable. Keep detailed records of doubling times and viability.

Protocol 2: Validating Autofluorescence Reduction via Plate Reader Assay

This method provides quantitative data on the effectiveness of your media optimization.

Materials:

- Cells adapted to different media conditions (e.g., Standard media vs. Optimized media).

- Black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate.

- Plate reader with top and bottom reading capabilities.

- PBS or low-fluorescence buffer (e.g., FluoroBrite DMEM).

Method:

- Seed Cells: Seed the same number of cells (e.g., 50,000 HeLa cells/well) into the 96-well plate in their respective media. Include multiple replicate wells for each condition and a set of blank wells (media only, no cells) for background subtraction [34].

- Incubate: Incubate the plate overnight to allow cells to adhere and spread.