Targeted Nanoparticle Probes for Diagnostic Fluorescence Imaging: Advances, Applications, and Clinical Translation

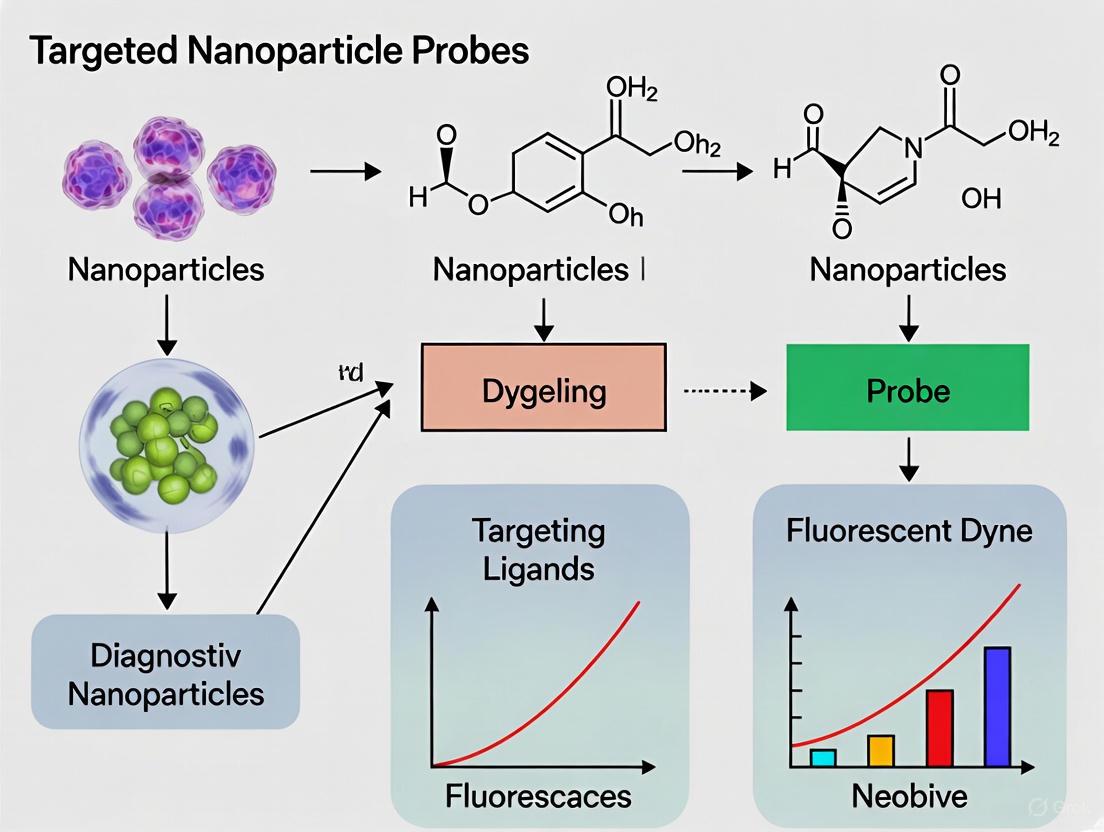

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in targeted nanoparticle probes for diagnostic fluorescence imaging, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Targeted Nanoparticle Probes for Diagnostic Fluorescence Imaging: Advances, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in targeted nanoparticle probes for diagnostic fluorescence imaging, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of fluorescent nanomaterial design, including quantum dots, metal nanoclusters, and carbon dots, and their sensing mechanisms such as FRET and PET. The scope extends to methodological applications in detecting biomarkers, small molecules, and pathogens, alongside detailed protocols for probe optimization and troubleshooting common issues like photobleaching and high background. Finally, the article presents a comparative analysis of different nanoprobes and targeting ligands, discusses validation strategies, and critically assesses the challenges and future directions for clinical translation, including the role of AI and multimodal imaging.

The Building Blocks: Understanding Fluorescent Nanoprobes and Their Core Mechanisms

Fluorescent probes are sophisticated chemical tools critical for diagnostic fluorescence imaging, enabling the visualization and quantification of biological targets at the molecular level. These probes function as molecular-level sensors that can detect and image specific biomarkers, providing invaluable insights for early disease diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and pharmaceutical development [1]. The design of targeted nanoparticle probes integrates principles from nanotechnology, molecular recognition, and photophysics to create highly sensitive and specific imaging agents. This application note details the core architectural components of fluorescent probes—the recognition unit, fluorophore, and connector—and provides experimental protocols for their development and validation within the context of advanced diagnostic imaging research.

Core Components and Their Functions

A fluorescent probe is a synthesized molecule that combines molecular recognition with signal transduction. Its effectiveness hinges on the integrated function of three fundamental components, each fulfilling a distinct and essential role [1].

Diagram 1: Core Architecture of a Fluorescent Probe

This diagram illustrates the core architecture of a fluorescent probe, showing the relationship between the three key components and their interaction with the target analyte.

Recognition Unit (Receptor)

The recognition unit is the targeting moiety of the probe, responsible for its specificity. This component is engineered to selectively bind to a target analyte—such as a protein, ion, nucleic acid, or specific cell type—through high-affinity molecular interactions [1]. The binding event is the initial trigger that ultimately leads to a measurable fluorescent signal.

- Function: Selective binding to the target analyte.

- Design Principle: The choice of recognition unit is dictated by the nature of the target. Common examples include:

- Antibodies or antibody fragments: For high-affinity binding to specific protein epitopes.

- Aptamers: Short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that fold into specific 3D structures for target binding.

- Small molecule ligands: Such as folic acid for targeting folate receptors overexpressed on certain cancer cells.

- Peptides: Engineered sequences for targeting specific cellular receptors.

- Chelators: For selective coordination of metal ions (e.g., NS4 receptor for Cu(I)) [2].

Fluorophore (Fluorescence Unit)

The fluorophore is the signal generator of the probe. It is a molecule that absorbs light at a specific wavelength and, after a short excited-state lifetime, re-emits light at a longer, lower-energy wavelength [3] [4]. The photophysical properties of the fluorophore directly determine the sensitivity, depth penetration, and detectability of the probe.

- Function: Absorption of excitation light and emission of fluorescent signal.

- Key Photophysical Properties:

- Brightness: The product of the molar extinction coefficient (ε, capacity for light absorption) and the fluorescence quantum yield (Φ, efficiency of photon conversion) [3] [4]. A higher brightness enables lower detection limits.

- Stokes Shift: The difference between the peak absorption (excitation) and emission wavelengths. A large Stokes shift minimizes spectral overlap, reducing background noise and improving signal clarity [3] [4].

- Excitation/Emission Wavelength: For in vivo imaging, fluorophores emitting in the near-infrared (NIR) range (650–900 nm) are preferred due to reduced tissue autofluorescence and superior tissue penetration [5].

Connector (Spacer)

The connector, or spacer, is the covalent linker that connects the recognition unit to the fluorophore. While often a simple molecular chain, its design is critical for maintaining the probe's functionality.

- Function: Spatially links the recognition unit and fluorophore.

- Design Considerations:

- Length: The connector must be optimized to ensure that the fluorophore does not sterically hinder the binding of the recognition unit to its target.

- Rigidity/Flexibility: The chemical nature of the linker can influence the distance and orientation between the receptor and fluorophore, which is crucial for sensing mechanisms like FRET [1].

- Biocompatibility and Stability: The connector must be stable in the biological environment to prevent premature cleavage of the probe before it reaches its target.

Fluorescent Nanomaterials and Sensing Mechanisms

Classes of Fluorophores for Nanoprobes

The advancement of nanotechnology has expanded the palette of available fluorophores beyond traditional organic dyes. The following table compares key classes of fluorophores used in constructing targeted nanoparticle probes.

Table 1: Comparison of Fluorescent Nanomaterials for Diagnostic Probes

| Material Class | Core Composition | Size Range | Key Advantages | Limitations & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Dots (QDs) [1] [5] | CdSe, CdTe, PbS, etc. | 2-10 nm | High brightness, excellent photostability, size-tunable emission. | Potential heavy metal toxicity, large size may alter bio-distribution. |

| Carbon Dots (CDs) [1] | Carbon, Nitrogen | < 10 nm | Good biocompatibility, low toxicity, tunable emission, facile synthesis. | Generally lower brightness compared to QDs. |

| Metal Nanoclusters (MNCs) [1] | Au, Ag atoms | ~1-2 nm | Ultra-small size, good photostability, low toxicity. | Moderate brightness. |

| Silicon Rhodamine Dyes [6] | Organic (Si-rhodamine) | < 2 nm | NIR emission, cell permeability, high brightness for small molecules. | Requires chemical conjugation. |

| Fluorescent Proteins (FPs) [6] | Protein (e.g., GFP) | ~4 nm (diameter) | Genetically encodable, ideal for intracellular expression. | Large size, relatively low photostability, can perturb fused protein function. |

Fundamental Sensing Mechanisms

The interaction between the probe and its target induces a photophysical change in the fluorophore. The primary mechanisms exploited in probe design are summarized below.

Diagram 2: Key Fluorescent Probe Sensing Mechanisms

This diagram outlines the logical flow of the three primary sensing mechanisms: FRET, PET, and ICT, which form the basis for signal generation in fluorescent probes.

- Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET): A distance-dependent energy transfer between two light-sensitive molecules (a donor and an acceptor). Target binding alters the distance between the donor and acceptor, changing the FRET efficiency and the resulting fluorescence output [1].

- Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET): In this mechanism, the recognition unit acts as an electron donor or acceptor that quenches the fluorophore's fluorescence. Binding of the target analyte blocks this electron transfer, resulting in a fluorescence "turn-on" response [1] [2].

- Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT): Probes designed with an electron donor and acceptor linked through a conjugated π-system exhibit a "push-pull" electronic effect. Target binding to either the donor or acceptor moiety alters the electronic properties of the system, leading to a shift in the emission wavelength [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Conjugation of a Targeting Ligand to a NIR Fluorophore via a PEG Spacer

This protocol describes a standard method for synthesizing a targeted fluorescent probe, using a folate-targeted cyanine dye as a model system for cancer cell imaging [5].

Objective: To conjugate folic acid (recognition unit) to Cy5.5 (fluorophore) using a heterobifunctional Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) spacer (connector) to create a probe for targeting folate receptor-positive cells.

Materials:

- Folic acid

- Cy5.5-NHS ester (commercially available, e.g., from Thermo Fisher Scientific [3])

- Heterobifunctional PEG Spacer (e.g., NH₂-PEG-COOH, MW: 2000 Da)

- Coupling Reagents: N,N'-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Anhydrous Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)

- Purification Equipment: Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) columns, e.g., Sephadex LH-20 or PD-10 desalting columns.

Procedure:

- Activation of Folic Acid:

- Dissolve 10 mg of folic acid and a 5x molar excess of DCC and NHS in 1 mL of anhydrous DMSO.

- React for 12 hours at room temperature with constant stirring.

- Centrifuge to remove the precipitated dicyclohexylurea (DCU) byproduct. The supernatant contains activated folic acid.

Conjugation to PEG Spacer:

- Add the activated folic acid solution dropwise to a solution of NH₂-PEG-COOH (15 mg in 1 mL DMSO).

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 6 hours at room temperature with stirring. This yields Folate-PEG-COOH.

Activation of Folate-PEG-COOH:

- React the Folate-PEG-COOH intermediate with a 5x molar excess of DCC/NHS (as in Step 1) for 12 hours.

- Centrifuge to remove DCU. The supernatant contains Folate-PEG-NHS.

Conjugation to Fluorophore:

- Add the Folate-PEG-NHS solution to a solution of Cy5.5-NHS ester (2 mg in 0.5 mL DMSO).

- Adjust the pH to ~8.5 using N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) to facilitate the reaction between the NHS ester and the amine group.

- React for 4 hours in the dark with stirring.

Purification and Characterization:

- Purify the final product, Folate-PEG-Cy5.5, using size exclusion chromatography (Sephadex LH-20) with DMSO as the eluent to separate the conjugate from unreacted dyes and coupling reagents.

- Characterize the product using analytical HPLC and confirm its molecular weight with Mass Spectrometry (MS).

- Determine the concentration and labeling efficiency by measuring the absorbance at 675 nm (for Cy5.5) and using its known molar extinction coefficient.

Protocol: Validation of Probe Functionality and Specificity In Vitro

Objective: To confirm that the synthesized fluorescent probe specifically binds to its cellular target and generates a detectable signal.

Materials:

- Cell Lines: Folate receptor-positive (e.g., KB cells) and receptor-negative (e.g., A549 cells) as a negative control.

- Complete Cell Culture Media

- Synthesized Folate-PEG-Cy5.5 probe

- Free Folic Acid (for competitive inhibition assay)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde)

- Mounting medium with DAPI

- Imaging Equipment: Confocal or fluorescence microscope with a Cy5.5-appropriate filter set.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation:

- Seed KB and A549 cells onto glass-bottom culture dishes or chamber slides and culture for 24-48 hours until 70-80% confluent.

Probe Incubation:

- Divide the KB cells into two groups: an experimental group and a competition group.

- Pre-treat the competition group with a 100x molar excess of free folic acid for 30 minutes.

- To all groups (KB experimental, KB competition, and A549), add the Folate-PEG-Cy5.5 probe at a concentration of 100 nM in culture media.

- Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C in a CO₂ incubator.

Washing and Fixation:

- Gently wash the cells three times with PBS to remove unbound probe.

- Fix the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash again with PBS.

Imaging and Analysis:

- Mount the samples and image using a fluorescence microscope.

- Use identical exposure settings across all samples to allow for quantitative comparison.

- Expected Outcome: Strong fluorescence should be observed only in the folate receptor-positive KB cells (experimental group). This signal should be significantly reduced in the competition group (pre-treated with free folic acid) and absent in the A549 (receptor-negative) cells, confirming the specificity of the probe.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Probe Development and Testing

| Item | Function/Application | Example Vendors/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule Fluorophores | Signal generation; available with reactive groups (NHS, maleimide) for conjugation. | Thermo Fisher Scientific (DyLight, Alexa Fluor series) [3]. |

| Quantum Dots | Highly bright and photostable nanocrystals for multiplexed imaging. | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Qdot nanocrystals) [3]. |

| Heterobifunctional PEG Linkers | Biocompatible spacers (e.g., NH₂-PEG-COOH, MAL-PEG-NHS) to connect recognition and fluorescence units. | Broadly available from chemical suppliers (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich, Creative PEGWorks). |

| Coupling Reagents | Facilitate the formation of amide bonds between components (e.g., DCC, EDC, NHS). | Standard chemical suppliers (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich, TCI). |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography Media | Purification of conjugated probes from reaction mixtures. | Cytiva (Sephadex), Bio-Rad (Bio-Gel P), or pre-packed PD-10 columns. |

| Fluorescent Microscopes & Scanners | Detection and spatial resolution of probe signal in cells and tissues. | Major instrument manufacturers (e.g., Zeiss, Leica, Olympus). |

| Flow Cytometers | Quantitative analysis of probe binding and uptake at the single-cell level. | BD Biosciences, Beckman Coulter [4]. |

| Spectrofluorometers | Characterization of probe photophysical properties (excitation/emission spectra, quantum yield). | Horiba, Agilent. |

Fluorescent sensing mechanisms are the cornerstone of modern diagnostic fluorescence imaging, enabling researchers to visualize biological processes at the molecular level with exceptional sensitivity and specificity. These mechanisms, including Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET), Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT), and Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE), form a versatile toolkit for developing advanced nanoparticle probes. Each mechanism operates on distinct photophysical principles that translate molecular recognition events into measurable optical signals, providing real-time insights into cellular environments, disease biomarkers, and therapeutic responses [7] [8]. The strategic selection and integration of these mechanisms allow for the rational design of probes that can overcome the limitations of conventional imaging agents, such as poor photostability, low signal-to-noise ratios, and limited targeting capabilities [9].

The significance of these mechanisms extends beyond basic research into translational medicine, where they facilitate early disease diagnosis, intraoperative guidance, and therapeutic monitoring. For instance, FRET-based systems excel at reporting molecular proximity and enzymatic activity, while PET-based constructs offer binary switching behavior ideal for ion detection. ICT probes provide ratiometric measurements that are resilient to environmental variables, and AIEgens overcome the aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) that plagues traditional fluorophores [10] [11]. When incorporated into targeted nanoparticle platforms, these mechanisms enable the creation of sophisticated diagnostic agents with enhanced biodistribution, tumor accumulation, and multimodal capabilities. This document provides a detailed technical overview of each mechanism, supported by structured data comparisons, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to guide their application in targeted fluorescence imaging research.

Fundamental Principles and Characteristics

The four key mechanisms—FRET, PET, ICT, and AIE—operate through distinct photophysical processes that dictate their application scope and experimental design. FRET is a distance-dependent energy transfer process between a donor fluorophore and an acceptor moiety, occurring through non-radiative dipole-dipole coupling. This mechanism requires significant spectral overlap between donor emission and acceptor absorption, and efficiency decreases with the sixth power of the distance between the pair, typically effective in the 1-10 nm range [12] [8]. FRET is particularly valuable for monitoring molecular interactions, conformational changes, and enzymatic activities in biological systems.

PET functions as an electron transfer switch where a receptor moiety, upon binding with an analyte, alters the electron transfer rate to a fluorophore, resulting in fluorescence quenching or enhancement. This "on-off" switching behavior makes PET probes highly sensitive to specific ions and small molecules [10] [8]. ICT involves a unidirectional electron flow between donor and acceptor groups within the same molecule, resulting in solvatochromic shifts in emission spectra. These probes are exceptionally responsive to microenvironmental changes such as polarity, viscosity, and pH, enabling ratiometric measurements that internal reference for more accurate quantification [8].

AIE represents a distinctive photophysical phenomenon where luminogens are non-emissive in molecularly dispersed states but exhibit strong fluorescence upon aggregation. This behavior directly counters the ACQ effect and is primarily attributed to the restriction of intramolecular motions (RIM), including rotation and vibration, which suppresses non-radiative decay pathways [13] [11]. Tetraphenylethylene (TPE) stands as a prototypical AIE luminogen with a propeller-shaped structure that prevents π-π stacking in aggregated states, making it particularly valuable for imaging in crowded biological environments [11].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Fluorescent Sensing Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Working Principle | Key Advantages | Typical Detection Limits | Primary Applications in Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRET | Distance-dependent energy transfer between donor and acceptor | Distance sensitivity (1-10 nm), rationetric capability, multiplexing potential | Nanomolar (nM) range | Enzyme activity monitoring, protein-protein interactions, nucleic acid detection |

| PET | Electron transfer from receptor to fluorophore core (on-off switching) | High contrast ratio, modular design, sensitivity to specific analytes | Picomolar (pM) to nanomolar (nM) range [7] | Ion detection (Hg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺), pH sensing, redox status monitoring |

| ICT | Charge redistribution across donor-acceptor framework | Ratiometric output, large Stokes shifts, environmental sensitivity | Nanomolar (nM) range [7] | Microenvironment polarity mapping, pH sensing, metal ion detection |

| AIE | Emission enhancement via restricted intramolecular motion in aggregate state | High photostability, strong aggregate-state emission, low background | Nanomolar (nM) range (e.g., hydrazine detection) [7] | Cellular organelle imaging, protein aggregation tracking, tumor margin delineation |

Table 2: Nanoprobe Design Considerations for Different Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Optimal Fluorophore Types | Compatible Nanoparticle Platforms | Key Design Parameters | Common Targeting Ligands |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRET | Cyanine dyes, quantum dots, TPE derivatives [13] | Liposomes, polymeric NPs, gold nanoparticles | Donor-acceptor spectral overlap, distance (1-10 nm), orientation factor | Antibodies, peptides, aptamers [9] |

| PET | Anthracene, rhodamine, BODIPY derivatives | Silica nanoparticles, dendrimers | Receptor-fluorophore electronic coupling, binding affinity | Small molecules, ionophores |

| ICT | D-π-A structured fluorophores with push-pull systems | Polymer-based nanoparticles, mesoporous silica | Donor/acceptor strength, conjugation length, solvent polarity | Peptides, antibody fragments [14] |

| AIE | TPE derivatives, hexaphenylsilole analogs | AIEgen self-assemblies, polymer-AIEgen conjugates [15] | Rotor structure flexibility, aggregation propensity, hydrophilic-lipophilic balance | cRGD peptides [14], nuclear localization signals |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: FRET-Based Hypoxia Detection Using AIE Nanoprobe

This protocol details the synthesis and application of a FRET-based "off-on" AIE nanoprobe for detecting hypoxic niches in tumor sections, adapted from a published study [13]. The probe leverages azobenzene (Azo) as a hypoxia-responsive linker and quencher, with tetraphenylethene (TPE) as the AIE-active fluorophore.

Reagents and Materials

- TNNT dimer: Synthesized by conjugating two TPE units via an Azo bridge

- DSPE-PEG₂₀₀₀: For nanoparticle stabilization and PEGylation

- Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF): For synthesis and purification

- Dichloromethane (DCM): For extraction and washing

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS): For biological experiments

- 4T1 breast cancer cell line: For in vitro and in vivo models

- Anaerobic chamber: For creating hypoxic conditions (1% O₂)

- Dialysis tubing: Molecular weight cutoff 3.5 kDa

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Synthesis of TNNT Dimer

- Dissolve TPE-COOH (1.0 mmol) and Azo bridge reagent (0.5 mmol) in 50 mL anhydrous DMF

- Add DCC (1.1 mmol) and DMAP (0.1 mmol) as coupling catalysts

- React under nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature for 12 hours with stirring

- Monitor reaction progress by thin-layer chromatography (TLC)

- Precipitate product in ice-cold water and purify by silica gel column chromatography using DCM/hexane (3:1) as eluent

- Characterize product by ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, and mass spectrometry [13]

Step 2: Preparation of PEGylated Nanoassemblies (p-TNNT NAs)

- Dissolve TNNT dimer (5 mg) in 1 mL THF

- Add DSPE-PEG₂₀₀₀ (1 mg in 0.5 mL THF) at 20 wt% ratio

- Inject solution rapidly into 10 mL deionized water under sonication

- Remove THF by dialysis against PBS (pH 7.4) for 6 hours

- Filter through 0.22 μm membrane to sterilize and remove aggregates

- Characterize particle size (expected ~110 nm), PDI (<0.2), and zeta potential by dynamic light scattering [13]

Step 3: In Vitro Hypoxia Response Validation

- Culture 4T1 cells in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C, 5% CO₂

- Incubate cells with p-TNNT NAs (10 μg/mL) for 4 hours

- Divide cells into two groups: normoxic (21% O₂) and hypoxic (1% O₂) conditions

- Maintain hypoxic group in anaerobic chamber for 6 hours

- Image cells using confocal microscopy with 405 nm excitation and 460 nm emission collection

- Quantify fluorescence intensity using ImageJ software

Step 4: In Vivo Administration and Tumor Section Imaging

- Establish 4T1 tumor-bearing mouse models (n=5 per group)

- Inject p-TNNT NAs (2 mg/kg) via tail vein

- Allow 24 hours for circulation and tumor accumulation

- Euthanize mice and excise tumors

- Immediately prepare fresh-frozen tumor sections (8 μm thickness)

- Image sections without fixation or staining using fluorescence microscopy

- Compare with positive control (pimonidazole hydrochloride) using immunofluorescence

Technical Notes and Troubleshooting

- Critical Step: Maintain anaerobic conditions throughout hypoxic experiments to prevent Azo cleavage before imaging

- Quality Control: Ensure nanoassemblies have PDI <0.2 for uniform biodistribution

- Optimization: Adjust DSPE-PEG₂₀₀₀ ratio (10-30 wt%) based on particle stability and cellular uptake

- Validation: Confirm hypoxia specificity by comparing with HIF-1α immunohistochemistry

Protocol: ICT-Based Ratiometric Sensing for Microenvironment Mapping

This protocol describes the development and application of an ICT-based ratiometric probe for mapping tumor microenvironment properties such as pH and polarity [8].

Reagents and Materials

- D-π-A structured fluorophore: With strong donor and acceptor groups

- Targeting ligand: cRGD peptide for integrin targeting [14]

- Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA): For nanoparticle encapsulation

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer: With capability for ratio measurements

- Confocal microscope: With spectral imaging capability

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Probe Design and Synthesis

- Select electron-donating group (e.g., triphenylamine, dimethylamino)

- Choose electron-withdrawing group (e.g., cyano, aldehyde, imide)

- Connect via π-conjugated bridge to create push-pull system

- Characterize ICT efficiency through solvatochromism testing

- Conjugate with cRGD peptide via EDC/NHS chemistry

- Purify by HPLC and verify by mass spectrometry

Step 2: Nanoparticle Formulation and Characterization

- Dissolve ICT probe (1 mg) and PLGA (10 mg) in 2 mL acetone

- Add dropwise to 10 mL PVA solution (2% w/v) under sonication

- Evaporate organic solvent under reduced pressure

- Centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes to collect nanoparticles

- Resuspend in PBS and characterize size, loading efficiency, and stability

Step 3: Ratiometric Calibration

- Prepare standard solutions with varying pH (5.0-8.0) or polarity (different water-glycerol mixtures)

- Measure emission spectra with excitation at optimal wavelength

- Identify two emission peaks that shift in opposite directions

- Create calibration curve of intensity ratio versus parameter of interest

- Determine linear range and limit of detection

Step 4: Biological Validation

- Incubate nanoparticles with cells (1-100 μg/mL) for 2-4 hours

- Image using confocal microscope with two detection channels

- Calculate pixel-by-pixel ratio to generate parametric images

- Compare with commercial probes for validation

- Perform statistical analysis of ratio distributions in different cellular compartments

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

FRET-Based "Off-On" Hypoxia Sensing Mechanism

Diagram 1: FRET-Based "Off-On" Hypoxia Sensing Mechanism - This workflow illustrates the mechanism of a FRET-based AIE nanoprobe for tumor hypoxia detection. Under normoxic conditions, FRET occurs between TPE donors and Azo acceptors, quenching fluorescence. In hypoxic environments, azoreductase cleaves Azo linkers, disrupting FRET and restoring TPE emission for detection [13].

AIE Luminogen Design and Bioapplication Workflow

Diagram 2: AIE Luminogen Design and Bioapplication Workflow - This diagram outlines the fundamental AIE process from molecular design to bioimaging application. AIEgens are non-emissive in solution but form aggregates upon cellular uptake, activating emission through restricted intramolecular motion (RIM) for high-contrast bioimaging [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescent Probe Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes | Commercial Sources/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIE Luminogens | TPE derivatives, Hexaphenylsilole | Core fluorophores with aggregation-induced emission; ideal for cellular imaging and tracking in dense environments | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI Chemicals, custom synthesis |

| FRET Pairs | Cyanine dyes (Cy3/Cy5), TPE-Azo systems | Donor-acceptor pairs for distance-dependent sensing; optimize spectral overlap for efficiency | Lumiprobe, AAT Bioquest, custom conjugation |

| Targeting Ligands | cRGD peptides, HER2-binding peptides | Enhance specific cellular uptake; conjugate via NHS-ester or click chemistry | Bachem, GenScript, AAPPTec |

| Nanoparticle Matrix | PLGA, DSPE-PEG₂₀₀₀, mesoporous silica | Carrier systems for improved delivery, circulation time, and biocompatibility | Sigma-Aldrich, Avanti Polar Lipids |

| Enzyme Substrates | Azobenzene (hypoxia), MMP-cleavable peptides | Responsive elements for activatable probes; select based on target enzyme expression | Sigma-Aldrich, Peptides International |

| Characterization Tools | Dynamic Light Scattering, Spectrofluorometers | Determine particle size, PDI, and optical properties; validate probe performance | Malvern Panalytical, Horiba, Agilent |

The strategic implementation of FRET, PET, ICT, and AIE mechanisms provides researchers with a diverse toolkit for developing advanced fluorescent nanoprobes for diagnostic imaging. Each mechanism offers distinct advantages: FRET for distance-dependent sensing, PET for binary switching behavior, ICT for environmental responsivity, and AIE for high-contrast imaging in aggregate-prone biological environments. The integration of these mechanisms with targeted nanoparticle platforms enhances their diagnostic potential through improved specificity, sensitivity, and functionality.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on multimodal probes that combine multiple sensing mechanisms to overcome individual limitations and provide complementary information. The incorporation of artificial intelligence for probe design optimization and data analysis represents another promising direction [7]. Additionally, addressing challenges related to biocompatibility, regulatory approval, and manufacturing scalability will be crucial for successful clinical translation. As these technologies mature, they hold significant potential to advance personalized medicine through more precise diagnostic imaging and therapeutic monitoring capabilities.

Fluorescent nanomaterials have revolutionized diagnostic fluorescence imaging, offering superior photostability, tunable emission, and high brightness compared to traditional molecular probes. [16] [1] These materials, including quantum dots (QDs), metal nanoclusters (MNCs), carbon dots (CDs), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), provide researchers and drug development professionals with powerful tools for sensitive biomarker detection, deep-tissue imaging, and real-time monitoring of cellular processes. [16] [1] Their unique optical properties and nanoscale dimensions enable applications ranging from super-resolution microscopy to in vivo tumor targeting, forming a critical component of targeted nanoparticle probes in modern theranostics. [16] [17] This article provides a structured comparison of these nanomaterials, detailed experimental protocols for their application, and essential resources for their implementation in fluorescence imaging research.

Comparative Analysis of Fluorescent Nanomaterials

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of four major classes of fluorescent nanomaterials, highlighting their distinct advantages for diagnostic imaging applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Fluorescent Nanomaterials for Diagnostic Imaging

| Material Type | Size Range | Key Optical Properties | Primary Applications in Imaging | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Dots (CDs) | < 10 nm [18] | Tunable emission (UV-NIR), high QY up to 47.6% after passivation [18] [19] | Super-resolution imaging (STED, STORM), multiphoton imaging, FLIM, biomarker sensing [16] [17] | Excellent biocompatibility, low toxicity, facile synthesis, photostability [16] [17] | Variable QY based on precursor and synthesis method [18] |

| Metal Nanoclusters (MNCs) | Atomically precise (e.g., Au~21~, Au~22~) [19] | NIR emission, tunable QY (13.1% to 47.6% via atomic manipulation) [19] [20] | NIR bioimaging, biosensing [20] | Atomically precise structure, good biocompatibility, potential for atomic-level tuning [19] [21] | Complex synthesis requiring precise control [19] |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Nanoscale [1] | Size-dependent emission, high brightness, broad excitation [1] | Multiplexed biomarker detection, deep-tissue imaging [1] | High QY, narrow emission bands, excellent photostability [1] | Potential heavy metal toxicity, blinking effect [16] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Varies with structure [22] | Tunable emission via linker/metal choice, stimulus-responsive (e.g., piezochromic) [22] | Sensing, photocatalysis, potential for drug delivery & imaging [22] | Extremely high surface area, structural tunability, porous nature [22] | Stability can vary, potential toxicity of metal components [1] |

Application Notes for Diagnostic Imaging

Carbon Dots (CDs)

CDs excel in advanced optical imaging due to their exceptional photostability and tunable fluorescence. They are ideal probes for super-resolution microscopy techniques like STED (stimulated emission depletion) and STORM (stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy), breaking the diffraction limit to achieve nanoscale resolution. [16] Their large multiphoton absorption cross-sections enable high-resolution imaging deep within tissues, while their compatibility with fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) provides a contrast mechanism independent of probe concentration, facilitating quantitative cellular imaging. [16] [17] CDs can be engineered for specific targeting and multimodal imaging by integrating capabilities like photoacoustic or magnetic resonance imaging. [16]

Metal Nanoclusters (MNCs)

MNCs, particularly gold clusters, are emerging as programmable nanomaterials with customized structures and near-infrared (NIR) emission, which is beneficial for deep-tissue imaging due to reduced scattering and autofluorescence. [19] [20] Their photophysical dynamics, including non-radiative decay pathways and intersystem crossing, can be regulated at the atomic level. [19] [20] For instance, single-atom manipulation in a cluster pair (Au~21~ and Au~22~) inhibited non-radiative decay and accelerated intersystem crossing, significantly enhancing the photoluminescence quantum yield from 13.10% to 47.63%. [19] This atomic-level tunability makes MNCs powerful for designing highly sensitive and bright probes for biological applications. [21]

Quantum Dots (QDs) and Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

QDs are valued for their superior brightness and photostability in multiplexed biomarker detection. [1] However, their potential cytotoxicity requires careful consideration for in vivo applications. [16] MOFs offer a highly tunable platform where fluorescence properties can be modulated through linker selection, metal node choice, and postsynthetic modifications. [22] Their porous structure can be loaded with therapeutic agents or other contrast agents, making them promising theranostic platforms. [22]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Heavy Metal Ion Detection Using Carbon Dots

This protocol details the use of carbon dots as fluorescent probes for the sensitive and selective detection of heavy metal ions (e.g., Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺) in aqueous samples, based on the fluorescence quenching (FQ) mechanism. [18]

- Principle: The detection relies on the quenching of CD fluorescence upon binding with specific heavy metal ions. Mechanisms include static quenching, dynamic quenching, photoinduced electron transfer (PET), and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). [18] [1]

- Materials:

- Carbon Dots Solution: Synthesized, for example, via hydrothermal treatment of carbon precursors (e.g., citric acid, orange peel). [18]

- Standard Solutions: Of target metal ions (e.g., 1000 ppm Cu(NO~3~)~2~, HgCl~2~).

- Buffer Solution: To maintain constant pH (e.g., 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4).

- Fluorescence Spectrometer.

- Procedure:

- Preparation of Calibration Curve:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target metal ion in buffer.

- Mix a fixed volume of CD solution with each standard solution and incubate for 5-10 minutes at room temperature.

- Measure the fluorescence intensity (FI) of each mixture at the excitation and emission maxima of the CDs.

- Plot the FI (or F~0~/F, where F~0~ is the FI in the absence of the quencher) against the metal ion concentration to obtain a calibration curve. [18]

- Analysis of Unknown Sample:

- Mix the CD solution with the filtered water sample under the same conditions.

- Measure the FI and determine the concentration of the target metal ion using the calibration curve. [18]

- Preparation of Calibration Curve:

- Safety Notes: Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (gloves, safety glasses) when handling metal salt solutions. Dispose of waste according to institutional regulations for heavy metals.

Protocol: Regulating Photophysical Dynamics in Metal Nanoclusters

This protocol outlines the methodology for single-atom manipulation of gold nanoclusters to regulate their emission properties, as demonstrated for the Au~21~/Au~22~ system. [19]

- Principle: Adding a single-gold-atom complex to a surface defect on the Au~21~ nanocluster complements its structure, creating Au~22~. This atomic-level manipulation enhances structural rigidity, reduces non-radiative decay, and accelerates intersystem crossing, leading to higher photoluminescence quantum yield. [19]

- Materials:

- Precursor Solution: Purified [Au~21~(AdmS)~12~(PPh~2~py)~3~]⁺ nanoclusters in CH~2~Cl~2~. [19]

- Reactant: AuPPh~2~pyCl complex.

- Solvents: Anhydrous CH~2~Cl~2~, hexane.

- Instrumentation: Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS), fluorescence spectrometer, equipment for single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

- Procedure:

- Cluster Transformation:

- Add a solution of the AuPPh~2~pyCl complex to a CH~2~Cl~2~ solution of Au~21~ nanoclusters.

- Stir the mixture at room temperature and monitor the reaction by ESI-MS until the signal for [Au~22~(AdmS)~12~(PPh~2~py)~4~]²⁺ dominates. [19]

- Purification and Crystallization:

- Purify the crude product via solvent washing.

- Cultivate single crystals by diffusing hexane into the CH~2~Cl~2~ cluster solution over ~7 days. [19]

- Photophysical Characterization:

- Confirm the atomic structure of Au~21~ and Au~22~ by single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

- Record UV-Vis absorption spectra to observe distinct chromatic changes.

- Measure photoluminescence (PL) spectra and determine PL quantum yields (PLQY) to quantify the emission enhancement in Au~22~. [19]

- Cluster Transformation:

- Safety Notes: Perform all procedures involving organic solvents in a well-ventilated fume hood.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Fluorescence Sensing Mechanisms in Nanoprobes

The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanisms by which fluorescent nanoprobes, such as CDs and MNCs, detect analytes like metal ions.

Figure 1: Fluorescence Sensing Mechanisms.

Workflow for Nanocluster Synthesis and Tuning

This workflow outlines the key steps for synthesizing atomically precise metal nanoclusters and tuning their photophysical properties through single-atom manipulation.

Figure 2: Workflow for Nanocluster Synthesis and Tuning.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Fluorescent Nanomaterial Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Precursors (e.g., Citric Acid, Lignin) [18] [23] | Synthesis of Carbon Dots (CDs) via bottom-up hydrothermal methods. | Determines the core structure and influences the quantum yield and emission profile of the resulting CDs. [23] |

| Passivating Agents (e.g., PEG, PEI) [18] [24] | Surface passivation of CDs to enhance quantum yield and stability. | PEG passivation, for example, provides excellent long-term (e.g., 60 days) stability. [24] |

| Atomically Precise Precursors (e.g., Au~21~ clusters) [19] | Serving as a platform for single-atom regulation of photophysical properties. | Enables atomic-level control for structure-property correlation studies. [19] |

| Metal-Ligand Complexes (e.g., AuPPh~2~pyCl) [19] | Used for single-point defect complementation in metal nanoclusters. | Acts as a single-atom "patch" to fill surface defects, enhancing rigidity and emission. [19] |

| Flexible MOF Platforms (e.g., PCN-128) [22] | Matrix for postsynthetic chemical and mechanical modifications. | Its flexibility allows for piezochromic behavior and postsynthetic annulation reactions for bandgap tuning. [22] |

| Heteroatom Dopants (e.g., N, S) [18] [16] | Doping of CDs to modify electronic structure and optical properties. | Enhances quantum yield and enables sensing of specific analytes. [18] |

Core Principles: Linking Nanomaterial Properties to Diagnostic Function

The diagnostic efficacy of nanoparticle probes in fluorescence imaging is governed by a triad of fundamental physicochemical properties: size, morphology, and surface chemistry. These parameters collectively determine the probe's biodistribution, targeting efficiency, signal intensity, and clearance pathways. Size influences circulation half-life and penetration into target tissues; smaller nanoparticles (sub-10 nm) may exhibit renal clearance, while larger ones are often sequestered by the mononuclear phagocyte system [9] [25]. Morphology—including shape and structural architecture—affects optical properties, cellular uptake, and flow dynamics. Surface modification is critical for conferring colloidal stability, reducing nonspecific binding, and enabling active targeting through the attachment of ligands such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers [26] [9]. For fluorescence imaging specifically, precise control over these properties enhances quantum yield, improves photostability, and minimizes background noise, which is essential for sensitive biomarker detection.

The interplay of these properties directly impacts key performance metrics in diagnostic imaging. For instance, quantum dots (QDs) exhibit size-tunable emission wavelengths due to the quantum confinement effect; larger dots emit at longer wavelengths (e.g., red), while smaller dots emit at shorter wavelengths (e.g., blue) [27]. This allows for multiplexed imaging of multiple biomarkers simultaneously. Furthermore, surface functionalization with polyethylene glycol (PEG) can shield nanoparticles from opsonization, prolonging their circulation time and increasing their accumulation in target tissues via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, particularly in tumors [28] [29]. The following diagram illustrates how these core properties synergistically dictate the diagnostic function of nanoparticle probes.

Diagram 1: How nanomaterial properties dictate diagnostic function.

The relationship between nanomaterial properties and their resulting function can be quantitatively summarized to guide probe design. The following tables consolidate critical data on how specific property ranges lead to distinct functional outcomes in diagnostic applications.

Table 1: Influence of Nanoparticle Size on Diagnostic Functionality

| Size Range | Key Functional Outcomes | Imaging Implications | Reference Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 6 nm | Rapid renal clearance, reduced RES uptake, deep tissue penetration. | Shorter imaging windows, suitable for intraoperative imaging. | AuQDs (<2 nm) enable high-resolution cell imaging and renal clearance [25]. |

| 6–20 nm | Balanced circulation time and tumor accumulation via EPR effect. | Optimal for in vivo tumor targeting and sustained imaging. | Semiconductor QDs (2-8 nm) tuned for specific emission wavelengths [27]. |

| 20–100 nm | Prolonged circulation, high RES uptake (liver, spleen). | Potential for background signal in RES organs; requires stealth coating. | SPIONs (~20 nm) used as T2 MRI contrast agents [28]. |

| > 100 nm | Primarily sequestered by the RES; limited tumor penetration. | Limited utility for deep tissue imaging; potential for macrophage imaging. | Not a primary focus in modern fluorescent probe design [9]. |

Table 2: Impact of Nanomaterial Morphology and Composition on Performance

| Morphology/Type | Key Properties | Diagnostic Advantages | Limitations & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Dots (Spherical) | Size-tunable PL; high quantum yield (50-90%); photostable. | Multiplexed imaging; femtomolar sensitivity; real-time tracking [27]. | Potential heavy metal toxicity (CdSe); blinking can occur [27] [29]. |

| Gold Quantum Dots (AuQDs) | Ultra-small (<2 nm); intrinsic fluorescence; high biocompatibility. | Low toxicity; renal clearance; surface plasmon resonance enhancements [25]. | Complex synthesis for uniformity; quantum yields typically lower than semiconductor QDs [25]. |

| Gold Nanospheres | Tunable LSPR; strong light scattering. | CT contrast; photothermal therapy; surface-enhanced Raman scattering [30]. | Not intrinsically fluorescent; larger sizes limit clearance [25]. |

| Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Spherical) | Superparamagnetism; T2/T2* MRI contrast. | Multimodal imaging (MRI-Fluorescence); magnetic targeting [31] [28]. | Signal attenuation in MRI at high concentrations; can aggregate [28]. |

| Anisotropic Structures (e.g., Nanorods) | Shape-dependent optical properties; multiple plasmon bands. | Enhanced photostability; higher cellular uptake in some cases [26]. | More complex synthesis and functionalization [26]. |

Table 3: Common Surface Modifications and Their Functional Roles

| Surface Modification | Primary Function | Impact on Diagnostic Probe Performance |

|---|---|---|

| PEGylation | Increases hydrophilicity; reduces opsonization and RES uptake. | Prolongs circulation half-life; enhances passive tumor targeting via EPR [28] [29]. |

| Targeting Ligands (Antibodies, Peptides, Aptamers) | Enables active targeting of overexpressed biomarkers on cell surfaces. | Dramatically improves specificity and signal-to-noise ratio at the disease site [9] [29]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Linkers (e.g., pH-, enzyme-sensitive) | Controls release of payload or activation of signal in specific microenvironments. | "Activatable" probes that reduce background signal; enable sensing of pathological activity (e.g., MMPs in tumors) [26] [29]. |

| Dyes & Fluorophores | Provides imaging signal. | Enables fluorescence detection; FRET-based sensing with QDs as donors/acceptors [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Nanoprobe Synthesis and Evaluation

This section provides detailed methodologies for the synthesis, functionalization, and in vitro evaluation of targeted fluorescent nanoprobes, with a focus on gold quantum dots (AuQDs) and quantum dot-infused nanocomposites (QDNCs).

Protocol: Synthesis of Fluorescent Gold Quantum Dots (AuQDs) via Chemical Reduction

Principle: This protocol describes the synthesis of biocompatible, fluorescent AuQDs using chemical reduction of a gold salt (chloroauric acid, HAuCl₄) in the presence of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), which acts as both a reducing and a stabilizing agent [25].

Materials:

- Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Fraction V

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution, 1M

- Deionized water

- Dialysis membrane (MWCO 3.5-5 kDa)

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a 10 mL aqueous solution containing 1 mM HAuCl₄ and 5 mg/mL BSA in a glass vial.

- Reduction Initiation: Under vigorous stirring, rapidly add 100 µL of 1M NaOH to the solution. The mixture will gradually change color.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C for 6-12 hours. The formation of AuQDs will be indicated by the solution turning from pale yellow to a dark brown, exhibiting fluorescence under UV light.

- Purification: Transfer the resulting solution to a dialysis membrane and dialyze against deionized water for 24 hours, changing the water every 6-8 hours, to remove unreacted precursors and salts.

- Characterization:

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Confirm the formation of quantum-confined gold species by the absence of a peak at ~520 nm (characteristic of larger AuNPs) and the presence of absorption in the UV region.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Analyze the size, morphology, and dispersion of the AuQDs. The particles should be monodisperse and sub-2 nm in diameter.

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Measure the fluorescence emission spectrum, which is typically size-dependent and can be tuned across the visible range [25].

Protocol: Surface Functionalization of Nanoparticles for Active Targeting

Principle: This protocol outlines the conjugation of a targeting ligand (e.g., the RGD peptide, which targets αvβ3 integrin receptors overexpressed on tumor vasculature) to the surface of pre-synthesized nanoparticles (e.g., AuQDs or QDs) via EDC-NHS chemistry, which facilitates amide bond formation between carboxylic acids and amines [9].

Materials:

- Synthesized nanoparticles with surface carboxyl groups (-COOH)

- Targeting ligand (e.g., RGD peptide) with a primary amine group (-NH₂)

- EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride)

- NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide)

- MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5) or PBS (pH 7.4)

- Purification equipment (dialysis membrane or centrifugal filters)

Procedure:

- Activation of Carboxyl Groups: In 1 mL of MES buffer, mix the nanoparticle solution (containing ~1 mg of nanoparticles) with a 10-fold molar excess of EDC and NHS. React for 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation to form an amine-reactive NHS ester on the nanoparticle surface.

- Ligand Conjugation: Add a 20-50 fold molar excess of the targeting ligand (RGD peptide) to the activated nanoparticle solution. Adjust the pH to 7.4 if necessary using PBS. Allow the reaction to proceed for 4-6 hours at room temperature.

- Quenching and Purification: Quench the reaction by adding 10 µL of 2-mercaptoethanol or a small amount of hydroxylamine. Purify the conjugated nanoparticles using dialysis (MWCO appropriate for nanoparticle size) or centrifugal filtration to remove unreacted crosslinkers and peptides.

- Validation: Confirm successful conjugation using techniques such as:

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: A shift in the emission spectrum may occur.

- Zeta Potential Measurement: A change in surface charge indicates surface modification.

- Gel Electrophoresis: A shift in mobility can confirm conjugation [9].

Protocol: In Vitro Evaluation of Targeted Nanoprobe Binding and Specificity

Principle: This protocol assesses the binding specificity and cellular uptake of targeted versus non-targeted nanoprobes using fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry on receptor-positive and receptor-negative cell lines.

Materials:

- Receptor-positive cells (e.g., HUVECs for αvβ3 integrin)

- Receptor-negative cells (as a control)

- Targeted nanoprobes (RGD-conjugated)

- Non-targeted nanoprobes (PEGylated only)

- Cell culture medium and reagents

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Seed receptor-positive and receptor-negative cells in 12-well plates at a density of 2 x 10⁵ cells per well and culture for 24 hours until 70-80% confluent.

- Incubation with Nanoprobe: Dilute the targeted and non-targeted nanoprobes in serum-free medium. Aspirate the old medium from the wells and add 500 µL of the nanoprobe solution (e.g., 10-50 nM equivalent QD concentration). Incubate for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Washing: Remove the nanoprobe solution and wash the cells three times with cold PBS to remove unbound particles.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Trypsinize the cells, resuspend in PBS, and analyze immediately. The receptor-positive cells incubated with targeted nanoprobes should show significantly higher mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) than all control groups.

- Fluorescence Microscopy: For direct visualization, fix the washed cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, mount with a DAPI-containing medium, and image. Targeted probes should show distinct membrane or internalized fluorescence in receptor-positive cells only [9] [25].

- Competitive Binding Assay (Optional): Pre-incubate receptor-positive cells with a 100-fold excess of free RGD peptide for 30 minutes before adding the RGD-conjugated nanoprobes. A significant reduction in fluorescence signal confirms the specificity of the receptor-mediated binding.

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from synthesis to in vitro validation.

Diagram 2: Nanoprobe development and evaluation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for Developing Targeted Fluorescent Nanoprobes

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl₄) | Gold precursor for the synthesis of Au nanoparticles and AuQDs. | Starting material for the chemical reduction synthesis of AuQDs [25]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Biocompatible reducing and capping agent for nanoparticle synthesis. | Serves as both reductant and stabilizer in the AuQD synthesis protocol [25]. |

| EDC & NHS Crosslinkers | Carbodiimide crosslinkers for activating carboxyl groups for amide bond formation with amines. | Used to conjugate targeting ligands (e.g., RGD peptide) to the nanoparticle surface [9]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer coating to impart "stealth" properties, reducing nonspecific protein adsorption. | PEGylation of nanoparticles to prolong circulation time and improve biodistribution [28] [29]. |

| Targeting Ligands (Peptides, Aptamers) | Biological molecules that confer specific binding to overexpressed cellular receptors. | RGD peptide for targeting αvβ3 integrin in the functionalization protocol [9]. |

| Quantum Dots (CdSe/ZnS, InP) | Semiconductor nanocrystals with superior brightness and photostability for imaging. | Can be incorporated into nanocomposites (QDNCs) for ultra-sensitive biomarker detection [27]. |

| Fluorescence Dyes (e.g., Cy5.5) | Organic molecules used for labeling and signal generation in optical imaging. | Conjugated to nanoparticles for near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging [26] [30]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Applications in Biomarker Detection and Cancer Imaging

The early and accurate diagnosis of diseases relies on the sensitive detection of biomarkers, including proteins, nucleic acids, metal ions, and whole cells like Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) [32]. Nanoparticles have emerged as a revolutionary platform for this purpose, owing to their unique physical and chemical properties [33]. Their high surface-to-volume ratio allows for dense immobilization of recognition elements (e.g., antibodies, DNA strands), improving target capture efficiency and detection sensitivity [32]. Furthermore, nanomaterials such as noble metals and quantum dots possess distinctive optical properties, including tunable fluorescence and strong light-matter interactions due to localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), which are exploited to create highly sensitive and selective diagnostic assays [33] [32]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for using targeted nanoparticle probes in the fluorescence-based detection of diverse biomarkers, framed within the context of diagnostic imaging research.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions in nanoparticle-based detection assays.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Nanoparticle-Based Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Serve as potent fluorescence quenchers in FRET assays or as colorimetric reporters due to their tunable Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [33] [34]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Act as robust fluorophores with broad absorption, narrow, tunable emission, and high photostability for multiplexed fluorescence detection [33] [32]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Enable efficient separation and enrichment of target biomarkers (e.g., CTCs) from complex mixtures like blood using an external magnetic field [34]. |

| EpCAM Antibodies | Biological recognition elements conjugated to nanoparticles to specifically capture CTCs based on epithelial cell adhesion molecule expression [35] [34]. |

| DNAzymes | Catalytic DNA sequences used as recognition elements for specific metal ions (e.g., Pb²⁺); their activation leads to a detectable signal change [33]. |

| Specific Antibodies/Aptamers | Recognition elements (e.g., single-chain antibody fragments, aptamers) conjugated to nanoparticles to bind specific protein or nucleic acid targets [33] [32]. |

Detection Modalities and Nanomaterial Properties

Nanoparticles can be engineered to exploit various detection modalities. The selection of core material and surface functionalization dictates the mechanism of detection and the applicable biomarkers.

Table 2: Nanoparticle Probes for Diverse Biomarker Detection

| Biomarker Category | Detection Mechanism | Nanomaterial Used | Example Target & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Ions | Fluorescence quenching/recovery via FRET [33] | AuNPs, QDs [33] | Cu²⁺ sensor using pyridine-perylene-AuNPs; CN⁻ detection with QDs (μM concentration) [33] |

| Metal Ions | Colorimetric aggregation assay [33] | AuNPs [33] | K⁺ with crown-ether-AuNPs; Pb²⁺ with DNAzyme-AuNPs (μM concentration) [33] |

| Proteins/ Small Molecules | FRET-based displacement assay [33] | QDs, AuNPs [33] | TNT detection with QD-antibody and quencher; Glucose with dextran-AuNPs and Con A (1–40 mM) [33] |

| Nucleic Acids | Fluorescence or SERS enhancement on capture [32] | AgNPs, AuNPs [32] | Hepatitis B virus DNA with AgNP aggregates (LOD: 50 fM) [32] |

| Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) | Immunomagnetic capture & fluorescence identification [34] | Magnetic NPs, QDs [34] | CTC isolation via EpCAM-functionalized magnetic beads; identification with QD-labeled antibodies [34] |

| Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) | Size-based/deformability physical capture [35] | Microfluidic chips (often with nanotextured surfaces) [35] | Isolation of CTCs from blood based on larger size and stiffness, independent of surface markers [35] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: FRET-Based Detection of a Protein Biomarker

This protocol details the detection of a protein biomarker using Quantum Dots (QDs) as donors and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) as quenchers in a FRET-based assay [33].

Primary Materials:

- CdSe/ZnS core/shell QDs (emission tuned to match the acceptor's absorption).

- Spherical gold nanoparticles (d = 20 nm).

- Specific antibody or aptamer against the target protein.

- A dark quencher dye conjugated to a protein analog.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- QD Functionalization: Conjugate the QDs with the specific antibody fragment using standard EDC-NHS chemistry or via his-tag interactions. Purify the conjugates using size-exclusion chromatography [33].

- Quencher Assembly: Incubate the functionalized QDs with the quencher-dye-conjugated protein analog for 1 hour at room temperature to form the QD-quencher assembly. This quenches the QD fluorescence via FRET [33].

- Sample Incubation: Add the sample (e.g., serum) containing the target protein to the QD-quencher assembly. Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C with gentle shaking.

- Signal Measurement: Transfer the solution to a cuvette and measure the fluorescence intensity using a spectrophotometer. The presence of the target protein will displace the quencher, recovering the QD fluorescence signal [33].

- Data Analysis: Plot the fluorescence recovery against protein concentration to generate a calibration curve.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this FRET-based detection method:

Protocol: Immunomagnetic Capture and Fluorescence Detection of CTCs

This protocol describes the isolation of CTCs from whole blood using EpCAM-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles, followed by fluorescence identification [35] [34].

Primary Materials:

- EpCAM antibody-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles.

- Anti-CD45 antibodies conjugated with a fluorophore (e.g., FITC) for leukocyte staining.

- Fluorescent dyes (e.g., DAPI) for nuclear staining and QD-conjugated anti-cytokeratin antibodies for epithelial marker staining.

- Pre-treatment reagents (e.g., red blood cell lysis buffer).

- Magnetic separation stand.

- Fluorescence microscope or flow cytometer.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Blood Pre-processing: Collect peripheral blood in EDTA tubes. Lyse red blood cells using a commercial lysis buffer and centrifuge to obtain a pellet of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and CTCs [35].

- Immunomagnetic Capture: Resuspend the cell pellet in a buffer containing EpCAM-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles. Incubate for 30-60 minutes at 4°C with gentle rotation to allow binding.

- CTC Enrichment: Place the tube on a magnetic stand for 5-10 minutes. Carefully aspirate the supernatant containing unbound cells. Remove the tube from the magnet and wash the captured cells with PBS 2-3 times to remove non-specifically bound cells [34].

- Fluorescence Staining: Resuspend the magnetically captured cells in a buffer containing DAPI, CD45-FITC, and QD-anti-cytokeratin. Incubate for 30 minutes in the dark.

- Identification and Analysis: After washing, analyze the cells under a fluorescence microscope or flow cytometer. CTCs are typically identified as DAPI⁺ (nucleated), CD45⁻ (non-leukocyte), and cytokeratin⁺ (epithelial origin) [35].

The following diagram summarizes the immunomagnetic capture and identification process for CTCs:

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in CTC Heterogeneity

A significant challenge in CTC detection is their heterogeneity, driven largely by the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) [36]. This process confers metastatic potential and complicates detection based solely on epithelial markers like EpCAM. Understanding this pathway is crucial for designing robust detection panels.

Multiplexed Detection Logic for Improved Diagnostic Accuracy

Many biomarkers are aberrantly expressed in multiple diseases, making single-biomarker detection prone to false positives. Multiplexed detection of several biomarkers associated with a single disease significantly improves diagnostic accuracy [32]. The following logic workflow outlines the rationale and implementation of a multiplexed assay.

The rapid and accurate detection of pathogens is a cornerstone of modern disease control, particularly in cases with significant economic and food security implications, such as the African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV). This double-stranded DNA virus causes a highly contagious and lethal hemorrhagic disease in domestic and wild pigs, with mortality rates approaching 100% in naive populations [37] [38]. Since its emergence in China in 2018, ASFV has led to the culling of tens of millions of pigs globally, devastating the swine industry and threatening global food security [39] [38]. Given the absence of widely effective vaccines or treatments, disease control relies heavily on rapid diagnosis, strict biosecurity measures, and the culling of infected animals [40] [38].

Within this context, nanotechnology has emerged as a transformative tool for pathogen detection. Nanoparticle-based biosensors offer the potential for rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable diagnostics, addressing critical limitations of conventional methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which often require sophisticated laboratory infrastructure and skilled personnel [41] [42]. This application note details how engineered nanoparticles, particularly within fluorescence imaging systems, are being leveraged to detect ASFV with high sensitivity and specificity. We frame these technological advances within the broader thesis of developing targeted nanoparticle probes for diagnostic fluorescence imaging, highlighting their role in advancing personalized medicine and point-of-care diagnostics [41] [43].

Nanoparticle-Based Case Studies in ASFV Detection

The application of nanoparticles in ASFV diagnostics primarily focuses on enhancing the sensitivity, specificity, and speed of nucleic acid detection. The following case studies illustrate the practical implementation of these technologies.

Case Study 1: Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) Biosensor for Multi-Genotype ASFV Detection

A proof-of-concept biosensor utilizing gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) was developed to detect the highly conserved p72 gene of ASFV across multiple genotypes. The system employs oligonucleotide probes adsorbed onto the surface of AuNPs, which stabilize the nanoparticles in a salt solution. In the presence of the target ASFV DNA sequence, the probes hybridize with the target, leading to a change in the surface properties of the AuNPs. This change causes nanoparticle aggregation upon salt addition, resulting in a visible color shift from red to blue that can be detected spectrophotometrically [42].

Key Performance Metrics:

- Sensitivity: Successfully detected 550 copies of synthetic ASFV DNA.

- Specificity: Demonstrated no cross-reactivity with non-target bacterial DNA.

- Genotypic Coverage: In-silico analysis using Clustal Omega for multiple sequence alignments showed that probes 2 (40 bp, 50.0% GC content) and 5 (60 bp, 54.2% GC content) provided strong binding across multiple ASFV genotypes.

- Rapidity: The core detection reaction was completed within 5 minutes [42].

This system underscores the importance of probe design, with statistical analysis revealing that GC content was significantly correlated with sensitivity (Spearman’s ρ = -0.80, p = 0.016) [42].

Case Study 2: CRISPR-Cas12a/Gold-Nanoparticle Lateral Flow Assay

Researchers have integrated the collateral cleavage activity of CRISPR-Cas12a with gold nanoparticle-based lateral flow strips to create a portable, instrument-free diagnostic (termed "Cas-gold"). Upon recognition of a target ASFV DNA sequence (e.g., from the DNA polymerase or pp220 genes), the activated Cas12a enzyme indiscriminately cleaves a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) reporter. This cleavage event can be configured on a lateral flow strip, where the intact reporter molecule captures AuNP-antibody conjugates, producing a visible test line. When cleavage occurs, the reporter is destroyed, and the test line disappears, indicating a positive result [40].

Key Performance Metrics:

- Sensitivity: Comparable to the gold-standard qPCR method when tested on veterinary samples (blood and anal swabs).

- Specificity: The Cas12a/crRNA complex showed high specificity for ASFV, with no cross-reactivity against other common swine pathogens like Pseudorabies virus (PRV) or Porcine circovirus (PCV). The system also demonstrated low tolerance for single- or double-nucleotide mutations in the target sequence.

- Utility: Enabled rapid, equipment-free detection suitable for field applications [40].

Case Study 3: Nano-Fluorescence Probes for Signal Enhancement

Fluorescent nanomaterials, such as quantum dots (QDs) and upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs), are being explored to overcome limitations of traditional fluorescent dyes, including photobleaching, autofluorescence, and limited tissue penetration. While directly documented in ASFV detection is limited in the searched literature, the principles are well-established in lymphatic imaging and are directly applicable to pathogen diagnostics [43]. Near-infrared (NIR) nano-fluorescent probes, in particular, offer deeper tissue penetration and reduced background signal by minimizing interference from biomolecules in biological samples [43]. These probes can be functionalized with targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) for specific binding to ASFV antigens or integrated into assays like loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) to enhance the fluorescence signal for ultrasensitive detection [44].

Table 1: Comparison of Featured Nanoparticle-Based ASFV Detection Platforms

| Platform | Core Nanoparticle | Detection Mechanism | Key Performance | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNP Biosensor [42] | Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) | Colorimetric (Aggregation) | 550 copies, 5 min, multi-genotype | Resource-limited field settings |

| CRISPR-Cas12a/AuNP [40] | Gold Nanoparticle (Lateral Flow) | Immunochromatography | Sensitivity comparable to qPCR | Specific, equipment-free field testing |

| Nano-Fluorescence Probes [43] | QDs, UCNPs, Organic Dyes | Fluorescence Signal Amplification | Enhanced brightness, stability, deep tissue penetration | High-sensitivity lab and clinical imaging |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AuNP Oligonucleotide Probe Biosensor for ASFV

This protocol is adapted from the proof-of-concept study for detecting ASFV via a colorimetric AuNP biosensor [42].

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Reagents for AuNP Biosensor

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Citrate-capped AuNPs | Signal transducer | ~20-40 nm diameter |

| Oligonucleotide Probes | Target capture | Designed against conserved p72 gene region (e.g., Probes 2 & 5 from [42]) |

| ASFV Target DNA | Analytic | Synthetic DNA or extracted viral DNA |

| Salt Solution (e.g., PBS, MgCl₂) | Induces aggregation | Concentration must be optimized |

| Spectrophotometer / Plate Reader | Signal readout | Measures absorbance shift; visual inspection is also possible |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Probe Adsorption: Incubate the citrate-capped AuNPs with the designed oligonucleotide probes for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) at room temperature. This allows the ssDNA probes to adsorb onto the AuNP surface via electrostatic interactions.

- Sample Incubation: Mix the probe-conjugated AuNPs with the prepared sample containing the target ASFV DNA. Allow the mixture to incubate for 5-20 minutes to facilitate specific hybridization between the probe and the target.

- Salt-Induced Aggregation: Introduce a optimized concentration of salt solution to the mixture. The presence of salt screens the repulsive charges between nanoparticles.

- Negative Result: If the target DNA is absent, the probes remain unhybridized and folded on the AuNP surface, failing to protect them from salt-induced aggregation. This causes a color change from red to blue.

- Positive Result: If the target DNA is present, probe-target hybridization creates a rigid DNA duplex that sterically stabilizes the AuNPs against aggregation, preserving the red color.

- Result Interpretation: Analyze the color change visually or quantitatively using a spectrophotometer to measure the absorbance ratio at wavelengths corresponding to dispersed (e.g., 520 nm) and aggregated (e.g., 620 nm) AuNPs.

Protocol: Cas12a/Gold-Nanoparticle Lateral Flow Assay

This protocol outlines the steps for a portable, paper-based ASFV detection method combining CRISPR-Cas12a and AuNPs [40].

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cas-gold Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Recombinant FnCas12a Protein | Target-activated nuclease enzyme |

| crRNA | Guides Cas12a to specific ASFV target (e.g., DNA Pol or pp220 gene) |

| RPA Reagents (TwistAmp basic kit) | Isothermal amplification of target DNA |

| ssDNA-FQ Reporter | Substrate for trans-cleavage (FAM-TTATT-Quencher) |

| Custom Lateral Flow Strip | Contains test (anti-FAM) and control line antibodies |

| Gold Nanoparticle-Antibody Conjugate | Visual signal reporter on the strip |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Nucleic Acid Amplification: Perform Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) on the extracted sample DNA at 39°C for 15-20 minutes to amplify the target ASFV gene region.

- CRISPR-Cas12a Reaction: Incubate the RPA-amplified product with the preassembled Cas12a/crRNA complex and the FAM-quencher labeled ssDNA reporter. If the target DNA is present, Cas12a is activated and cleaves the reporter, releasing the FAM molecule.

- Lateral Flow Detection: Apply the reaction mixture to the sample pad of the custom lateral flow strip.

- The solution migrates along the strip.

- The key innovation: The intact, uncleaved reporter molecule (present only in negative samples) is designed to be captured by antibodies at the test line, binding the AuNP conjugate and producing a visible band.

- Positive Result: Activation of Cas12a cleaves the reporter. The cleaved fragments cannot bind at the test line, so no band appears at the test line. A control line should always appear to indicate proper strip function.

- Negative Result: No Cas12a activation occurs, the intact reporter is captured at the test line, and a band appears at the test line.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core detection mechanism of the Cas-gold assay:

The Scientist's Toolkit

A successful nanoparticle-based diagnostic assay requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table catalogs essential components for developing and deploying these systems.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nanoparticle-Based Fluorescence Detection

| Reagent/Material | Category | Critical Function & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal Transducer | Colorimetric signal generation via aggregation or as a label in lateral flow assays. Size (10-40 nm) and surface chemistry are critical [40] [42]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) / UCNPs | Fluorescent Probe | Superior fluorescence properties for signal amplification. Offer high quantum yield, photostability, and size-tunable emissions. NIR variants reduce autofluorescence [43]. |

| CRISPR-Cas12a Protein | Molecular Recognizer | Provides high-specificity DNA targeting and signal amplification via trans-cleavage of reporters [39] [40]. |

| crRNAs | Targeting Guide | Designed against conserved ASFV genes (e.g., p72, DNA Pol, pp220). Design is crucial for assay sensitivity and genotypic coverage [40] [38]. |

| Oligonucleotide Probes | Targeting Probe | For functionalizing AuNPs or as fluorescent reporters. GC content, length, and secondary structure impact performance [42]. |

| RPA/ LAMP Kits | Amplification | Isothermal amplification for rapid, equipment-free target nucleic acid enrichment [39] [40] [44]. |

| Lateral Flow Strips | Readout Platform | Portable, user-friendly result visualization. Often require custom conjugation of antibodies with nanoparticles [40]. |

| Fluorescence Dyes (e.g., FAM) | Reporter Molecule | Label ssDNA reporters for Cas12a assays or primers for LAMP. Require compatible imaging systems [39] [44]. |

Nanoparticle-based biosensors represent a paradigm shift in the detection of pathogens like ASFV, moving diagnostics from centralized laboratories to the point of need. The case studies presented here—ranging from simple colorimetric AuNP sensors to sophisticated CRISPR-Cas/nanoparticle hybrids—demonstrate the potential for developing rapid, sensitive, and specific field-deployable tools. These advancements align with the broader thesis of creating targeted nanoparticle probes for diagnostic fluorescence imaging, offering a path toward personalized veterinary medicine and robust global disease surveillance networks [41] [43].

Despite the promising advances, challenges remain in the clinical translation of these nanoprobes, including ensuring batch-to-batch reproducibility, long-term stability, and navigating regulatory pathways [41]. Future research directions will likely focus on creating multiplexed detection systems to identify multiple pathogens or ASFV genotypes simultaneously, integrating these assays with smartphone-based readout technologies for data digitization, and further engineering nanoparticles to enhance their sensitivity and specificity. By addressing these challenges, nanoparticle-based diagnostics will play an increasingly critical role in controlling ASF and other transboundary animal diseases, ultimately safeguarding animal health and global food security.

The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect represents a fundamental principle in oncology, describing the pathological tendency of macromolecules and nanoparticles to accumulate preferentially in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues [45]. First observed in 1984 and formally named in 1986, this phenomenon has become a cornerstone for developing targeted cancer nanomedicines and imaging agents [45] [46]. The EPR effect stems from key pathophysiological abnormalities in solid tumors: defective vascular architecture with enhanced permeability, impaired lymphatic drainage, and unique inflammatory mediator production [45] [46]. Tumor vasculature exhibits irregular architecture, deficient basement membranes, and fenestrated structures that render them highly permeable to macromolecules, with gap sizes ranging from 100-780 nm [45] [46]. Simultaneously, the lack of efficient lymphatic drainage in tumor tissue prevents the removal of extravasated materials, leading to their prolonged retention [45].