Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents: A Comparative Analysis of Performance, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of targeted and non-targeted fluorescent agents, addressing key considerations for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents: A Comparative Analysis of Performance, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of targeted and non-targeted fluorescent agents, addressing key considerations for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles, molecular designs, and mechanisms of action underlying both agent classes. The review details methodological advances and diverse applications across bioimaging, disease diagnosis, and image-guided surgery, highlighting specific use cases from recent literature. Critical challenges such as photostability, targeting accuracy, signal-to-noise ratio, and biocompatibility are examined alongside current optimization strategies. The article concludes with a rigorous validation and performance comparison, evaluating specificity, sensitivity, and clinical translation potential to guide probe selection and future development in biomedical research.

Fundamental Principles and Molecular Design of Fluorescent Agents

Fluorescent imaging agents are injectable substances that enhance the visualization of biological processes, structures, or diseases when excited by light. These agents are fundamentally categorized into two classes: targeted and non-targeted. Their development and application are central to advances in biomedical research, diagnostics, and therapeutic monitoring, particularly in oncology [1] [2]. Targeted agents are engineered to bind specifically to molecular biomarkers, such as cell-surface receptors or enzymes, that are overexpressed in diseased tissues. This specificity aims to provide high-contrast images based on the molecular profile of the tissue. In contrast, non-targeted agents accumulate in tissues through passive physiological mechanisms, such as enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) in tumors or through general pharmacokinetic properties like vascular flow and hepatic clearance [3] [4]. The choice between these agents dictates the type of biological information obtained, influencing diagnostic accuracy and the potential for image-guided interventions.

Defining the Core Concepts

Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents

Non-targeted fluorescent agents are dyes that do not selectively bind to a specific molecular target. Their distribution within the body is governed by their intrinsic chemical properties and the general physiology of the tissue. A classic and widely used example is Indocyanine Green (ICG), an FDA-approved fluorophore that emits in the near-infrared (NIR) range [1] [5] [4]. After intravenous injection, ICG binds non-covalently to plasma proteins, confining it primarily to the bloodstream. This makes it an excellent tool for visualizing vascular flow, tissue perfusion, and identifying anatomical structures. In oncology, ICG can accumulate in tumors via the EPR effect, a passive phenomenon where macromolecules and particles preferentially extravasate and are retained in tumor tissue due to its leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage [4]. Another example is Methylene Blue (MB), which is also used in various clinical procedures [5]. The primary mechanism of non-targeted agents is passive accumulation, relying on physiological differences between normal and diseased tissues rather than molecular recognition.

Targeted Fluorescent Agents

Targeted fluorescent agents are molecularly engineered constructs designed to home in on specific biological targets. They are typically composed of two key elements: a targeting ligand and a fluorophore [3] [6]. The targeting ligand—which can be a peptide, antibody, or small molecule—confers specificity by binding with high affinity to a defined biomarker, such as a cell-surface receptor overexpressed on cancer cells. The attached fluorophore (e.g., IRDye800CW, Cy5.5) provides the detectable signal [1] [2]. A prominent example is Cytalux, an FDA-approved agent that consists of a folate analog conjugated to a fluorescent dye. It targets the folate receptor, which is highly expressed in ovarian and lung cancers, enabling tumor-specific imaging [6]. Other experimental agents include peptides like cRGD that target integrin αvβ3, and HN-1 peptide conjugates that target Discoidin Domain Receptor-1 (DDR-1) on various cancer cells [3] [6]. The mechanism of action is active targeting, which depends on the molecular interaction between the ligand and its receptor, often followed by internalization of the probe into the target cell [4].

Comparative Performance Analysis

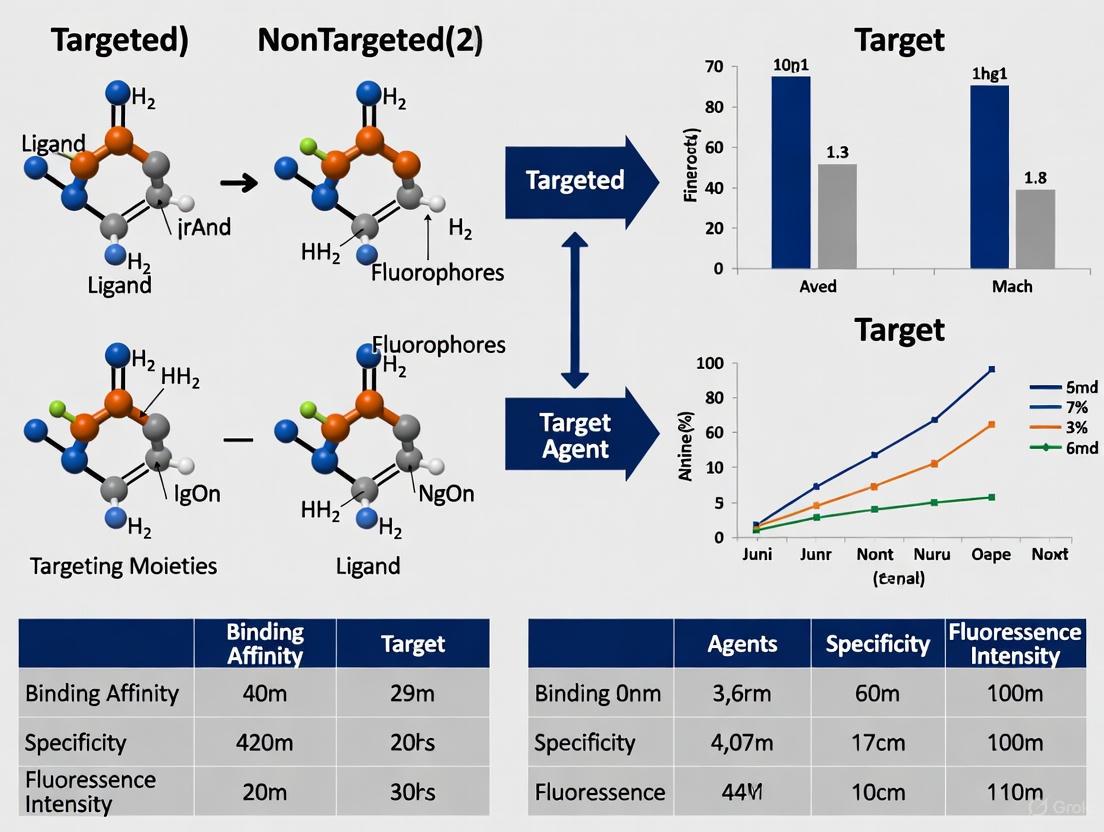

The practical differences between targeted and non-targeted agents are best understood through a side-by-side comparison of their key performance metrics in experimental and clinical settings. The table below summarizes these critical distinctions.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents

| Performance Characteristic | Targeted Agents | Non-Targeted Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Active binding to specific molecular targets (e.g., receptors, enzymes) [3] [6] | Passive accumulation based on physiology (e.g., EPR effect, vascular flow) [5] [4] |

| Molecular Specificity | High (e.g., Cytalux for folate receptor, cRGD for integrin αvβ3) [3] [6] | Low (e.g., ICG accumulation in leaky tumor vasculature) [4] |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) | Potentially high, but requires time for unbound agent clearance [4] | Variable; can be high initially but diminishes rapidly as agent clears from blood [5] |

| Optimal Imaging Time | Hours to days post-injection (allows for target binding and background clearance) [4] | Minutes to hours post-injection (capitalizes on pharmacokinetic distribution) [5] |

| Tumor Delineation | Excellent, defines molecular margins [2] | Good for perfusion, but margins can be diffuse [5] |

| Information Gained | Molecular and functional data (e.g., receptor expression levels) [3] [4] | Anatomical and physiological data (e.g., perfusion, tissue viability) [5] |

| Common Clinical Examples | Cytalux, antibody-IRDye800CW conjugates (in trials) [2] [6] | Indocyanine Green (ICG), Methylene Blue [1] [5] |

Quantitative data from preclinical studies further illuminates these performance differences. For instance, a study on the cRGD-ZW800-1 probe (targeting integrin αvβ3) demonstrated specific and prolonged accumulation in tumors with a high signal-to-background ratio [2]. In a head-to-head comparison, a novel DDR-1 targeted probe (Cy756-CHN-1) showed superior tumor affinity and fluorescence intensity in CAL27, SCC9, and 4T1 cell lines compared to non-targeted dyes [6]. Conversely, while ICG provides a strong signal in liver tumors, its specificity is derived from impaired biliary excretion in hepatocellular tissue rather than molecular targeting, which can lead to non-target background signal [5] [4]. The dissociation constant (Kd) of targeted probes is a key metric of affinity; for example, the KSP*-Cy5.5 probe targeting HER2 exhibits a high affinity with a Kd of 21 nM [3].

Table 2: Experimental Data from Preclinical Studies of Selected Agents

| Agent Name | Target / Mechanism | Key Experimental Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cy756-CHN-1 | DDR-1 (Peptide-targeted) | Superior fluorescence intensity and tumor affinity in CAL27, SCC9, and 4T1 cell lines in vitro and in mouse models. | [6] |

| KSP*-Cy5.5 | HER2 (Peptide-targeted) | High binding affinity with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 21 nM; effective for early-stage tumor detection. | [3] |

| ICG | Passive EPR / Vascular Flow | Effective for tumor detection and lymphatic mapping, but specificity is limited by non-target accumulation. | [5] [4] |

| cRGD-based probes | Integrin αvβ3 (Peptide-targeted) | Demonstrated long-lasting imaging signals in tumors, with persistence for over 24 hours. | [3] |

| MMP-responsive probe | MMP2/9 Enzymes (Activatable) | Selective activation in high MMP2/9 expression environments; enables combined imaging and photodynamic therapy. | [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate how the performance data for these agents is generated, below are detailed protocols for key experiments evaluating a targeted peptide-based probe and a non-targeted agent.

Protocol 1: Evaluating a Targeted Peptide-Based Probe In Vitro and In Vivo

This protocol, based on the development of DDR-1 targeted agents, outlines the process from synthesis to validation [6].

Objective: To synthesize, characterize, and validate the targeting efficacy and specificity of a novel peptide-fluorophore conjugate (e.g., Cy756-CHN-1).

Materials:

- Peptide Synthesis: Rink Amide MBHA resin, Fmoc-protected amino acids, coupling reagents (HBTU, HOBt), cleavage cocktail (TFA/TIS/water).

- Conjugation: IR-783 derivative (e.g., Cy756-COOH), dimethylformamide (DMF), triethylamine, purification columns (HPLC).

- Cell Culture: Target-positive cell lines (e.g., CAL27, SCC9), target-negative control cell lines, standard culture media and supplements.

- Imaging & Analysis: NIR fluorescence imaging system, confocal microscope, flow cytometer, software for signal quantification (e.g., ImageJ).

Methodology:

- Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS): Manually synthesize the HN-1 or CHN-1 peptide on Rink Amide MBHA resin using standard Fmoc chemistry. Couple amino acids sequentially using HBTU/HOBt activation. Cleave and deprotect the peptide from the resin using a TFA-based cocktail, then precipitate and purify via preparative HPLC.

- Fluorophore Conjugation: Conjugate the purified peptide to the NIR dye (e.g., Cy756-COOH) in DMF with triethylamine as a base. Purify the final conjugate (Cy756-CHN-1) using HPLC and confirm its structure with techniques like 1H NMR and HRMS.

- In Vitro Binding and Specificity:

- Culture target-positive (CAL27) and target-negative cells.

- Incubate cells with the Cy756-CHN-1 probe (e.g., 1 µM) for a set time (e.g., 2 hours) at 37°C.

- For competitive binding assays, pre-treat cells with an excess of unlabeled HN-1 peptide for 1 hour before adding the fluorescent probe.

- Analyze cells using flow cytometry and confocal microscopy to quantify uptake and visualize localization.

- In Vivo Tumor Imaging:

- Establish tumor xenograft models by subcutaneously injecting target-positive cells into mice.

- Once tumors reach a predetermined volume (e.g., 100-150 mm³), intravenously inject the Cy756-CHN-1 probe.

- Acquire non-invasive NIR fluorescence images at multiple time points post-injection (e.g., 0, 2, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours).

- Quantify the fluorescence signal intensity in the tumor region and adjacent normal tissue to calculate the tumor-to-background ratio (TBR).

- Ex Vivo Validation: After the final imaging time point, euthanize the animals, resect the tumors and major organs, and image them ex vivo to confirm probe distribution and accumulation.

Protocol 2: Assessing a Non-Targeted Agent for Perfusion and Tumor Delineation

This protocol details the use of ICG for evaluating tissue perfusion and tumor mapping, a common clinical and research application [5].

Objective: To utilize ICG fluorescence for real-time assessment of tissue perfusion and to visualize tumors via passive accumulation.

Materials:

- Contrast Agent: Indocyanine Green (ICG) powder, sterile water for reconstitution.

- Imaging System: Clinical or preclinical NIR fluorescence imaging system (e.g., FLARE, Pinpoint, PDE-neo).

- Animal Model or Patient: Tumor-bearing animal model or human patient undergoing surgery.

Methodology:

- Agent Preparation: Reconstitute ICG powder according to manufacturer instructions to achieve a standard concentration (e.g., 2.5 mg/mL).

- Dynamic Perfusion Assessment:

- Administer a bolus intravenous injection of ICG (dose varies by model/system, e.g., 0.1-0.3 mg/kg).

- Immediately initiate real-time video-rate fluorescence imaging of the region of interest (e.g., an anastomosis in bowel, a skin flap, or a tumor).

- Observe and record the arrival and wash-in of the fluorescent signal. The time from injection to tissue fluorescence provides a qualitative measure of perfusion.

- Tumor Delineation Imaging:

- Administer ICG intravenously (a similar or slightly higher dose than for perfusion).

- Allow a circulation time (e.g., 15-60 minutes) for the agent to passively extravasate and accumulate in the tumor via the EPR effect.

- Acquire fluorescence images of the surgical field. The tumor may appear as a uniformly fluorescent mass or, in the case of liver metastases, as a "negative" or "ring-shaped" fluorescent pattern due to disrupted biliary clearance.

- Data Analysis:

- Qualitative: Surgically resect the fluorescent tissue for histopathological confirmation.

- Semi-Quantitative: Calculate the Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) by dividing the mean fluorescence intensity of the target tissue (tumor) by the mean fluorescence intensity of adjacent normal tissue. This provides a pseudo-quantitative metric for comparison.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The functional difference between targeted and non-targeted agents stems from their engagement with biological pathways. The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate these core mechanisms and a typical experimental workflow.

Core Mechanism of Targeted Fluorescent Agents

This diagram illustrates the pathway by which a targeted agent, such as a peptide-dye conjugate, specifically binds to a cell-surface receptor to generate a signal.

Core Mechanism of Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents

This diagram shows the pathway of a non-targeted agent, like ICG, which relies on passive physiological processes for tissue accumulation.

Generic Workflow for Agent Evaluation

This flowchart outlines a standard experimental process for validating the performance of a new fluorescent agent, both targeted and non-targeted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research and development in fluorescent imaging require a suite of essential reagents, materials, and instrumentation. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Fluorescent Imaging Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorophores | ICG, IRDye800CW, Cy5.5, Cy7, Alexa Fluor dyes [1] [7] | The light-emitting component of the imaging agent. Chosen based on excitation/emission wavelengths, quantum yield, and photostability. |

| Targeting Moieties | cRGD peptide (for integrins), HN-1 peptide (for DDR-1), folate, antibodies (e.g., Panitumumab) [3] [6] | Provides molecular specificity by binding to biomarkers on target cells. |

| Cell Lines | CAL27 (oral squamous cell carcinoma), SCC9 (squamous cell carcinoma), 4T1 (breast cancer), U87MG (glioma) [3] [6] | Validated in vitro models that express (or lack) the target of interest for binding and specificity assays. |

| Animal Models | Mouse xenograft models (e.g., from CAL27, 4T1 cells) [6] | In vivo models for evaluating agent pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and imaging efficacy. |

| Synthesis & Purification | Rink Amide MBHA resin, Fmoc-amino acids, HBTU/HOBt, HPLC systems [6] [8] | Materials and equipment for solid-phase peptide synthesis and purification of final conjugates. |

| Imaging Instrumentation | NIR fluorescence imaging systems (e.g., IVIS, FLARE), Confocal Microscopes, Flow Cytometers [2] [5] | Devices to detect, quantify, and visualize fluorescence signals from in vitro and in vivo experiments. |

| Analysis Software | ImageJ, MATLAB, proprietary instrument software [7] | Tools for quantifying fluorescence intensity, calculating TBR, and processing image data. |

Fluorescent probes have revolutionized biomedical research and diagnostic imaging by enabling the visualization of molecular and cellular processes in real-time. The architectural design of these probes—encompassing the fluorophore, targeting moiety, and linker—directly dictates their performance, specificity, and applicability in complex biological systems. This guide provides a comparative analysis of fluorescent probe components, framing the evaluation within the critical research context of targeted versus non-targeted imaging strategies. Targeted agents use affinity ligands like antibodies or peptides to bind specific molecular signatures, offering high specificity, while non-targeted agents rely on passive accumulation or environmental activation, often providing broader applicability. Understanding this dichotomy is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select optimal probes for their specific experimental or clinical goals, from basic cell biology to image-guided surgery [9] [10].

Core Components of Fluorescent Probes

The molecular architecture of a fluorescent probe is a modular system where each component fulfills a distinct and critical function. The synergistic relationship between these parts determines the probe's overall efficacy.

- Fluorophore: This is the light-emitting component responsible for signal generation. Its core properties—including excitation/emission wavelengths, brightness (quantum yield), and photostability—are paramount. Ideal fluorophores for in vivo imaging, particularly in the near-infrared (NIR) window (650-900 nm), offer deep tissue penetration and minimal background autofluorescence [10].

- Targeting Moiety: This component confers specificity, directing the probe to a desired biological target such as a cell-surface receptor, enzyme, or nucleic acid. Common targeting ligands include antibodies, peptides (e.g., HN-1), small molecules (e.g., folate), or inhibitor scaffolds (e.g., FAP quinolone-based inhibitors) [11] [6].

- Linker/Spacer: This segment connects the fluorophore to the targeting ligand. It is not merely a tether; its chemical nature, length, and stability profoundly influence the probe's pharmacokinetics, binding affinity, and susceptibility to enzymatic cleavage. A well-designed linker ensures the targeting function is not sterically hindered by the fluorophore [9].

The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathways and logical relationships in the design and application of these probes, particularly contrasting targeted and non-targeted strategies.

Comparative Performance of Probe Architectures

The fundamental choice between a targeted and a non-targeted strategy has a profound impact on imaging outcomes. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, mechanisms, and performance metrics of these two approaches, providing a high-level objective comparison.

Table 1: General Performance Comparison of Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents

| Feature | Targeted Fluorescent Agents | Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Active binding to specific molecular targets (e.g., receptors, enzymes) | Passive accumulation via EPR effect or environmental activation (e.g., pH) |

| Primary Applications | Specific tumor phenotyping, receptor occupancy studies, pathway activation imaging | Broad tumor delineation, tissue perfusion assessment, first-line contrast |

| Key Strength | High specificity and molecular contrast | Wider applicability across tumor types; simpler development |

| Key Limitation | Target expression heterogeneity can limit application; larger size may reduce tissue penetration | Lower specificity can lead to false positives; background signal can be higher |

| Representative Probes | Antibody-dye conjugates (e.g., Panitumumab-IRDye800CW), peptide-dye conjugates (e.g., HN-1-Cy756) [6] | Indocyanine Green (ICG), Fluorescein [7] [10] |

Quantitative Comparison of Specific Probe Technologies

Beyond the conceptual overview, direct quantitative comparison of experimental data is crucial for probe selection. The following table consolidates performance metrics from recent studies on specific targeted and non-targeted agents.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Specific Fluorescent Probes

| Probe Name | Target / Mechanism | Key Experimental Findings | Reported Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cy756-CHN-1 [6] | DDR-1 (via HN-1 peptide) | Superior tumor affinity and fluorescence intensity in CAL27, SCC9, and 4T1 cell lines and mouse models. | High fluorescence intensity; Specific tumor accumulation demonstrated via competitive binding assays. |

| FTF Probes [11] | FAP (Fibroblast Activation Protein) | Effectively labeled cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) populations in solid tumors after both topical and intravenous delivery. | Validated labeling of CAF populations in vivo. |

| ICG (Indocyanine Green) [7] [10] | Passive Accumulation (EPR effect) | Widely used for intraoperative imaging; lacks tumor specificity, leading to non-target accumulation and potential false positives. | Non-specific contrast; Performance highly dependent on ROI selection [12]. |

| mTFP1/EYFP FRET Pair [13] | FRET Efficiency (For protein interaction studies) | Demonstrated a high fraction of donor engaged in FRET (f~D~ = 0.7), making it a superior couple for quantitative FRET-FLIM experiments in live cells. | f~D~ = 0.7; Minimal f~D~ (for fast acquisitions) = 0.65. |

| mCherry/EGFP FRET Pair [13] | FRET Efficiency (For protein interaction studies) | Exhibited a relatively low fraction of donor engaged in FRET compared to mTFP1/EYFP. | f~D~ = ~0.35 (Minimal f~D~ for fast acquisitions). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for validation, this section outlines detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the performance comparison.

Protocol: Evaluating Tumor Targeting and Specificity of Peptide-Dye Conjugates

This protocol is adapted from studies evaluating DDR-1-targeted agents like Cy756-CHN-1 [6].

- Aim: To synthesize and validate the tumor-targeting efficacy and specificity of a peptide-dye conjugate in vitro and in vivo.

- Synthesis:

- Peptide Synthesis: Manually synthesize the targeting peptide (e.g., HN-1 or CHN-1) using standard Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis (Fmoc-SPPS) on Rink Amide MBHA resin.

- Dye Conjugation: Employ a one-step Suzuki coupling reaction to conjugate a phenyl-modified cyanine dye (e.g., derivative of IR-783) to the synthesized peptide, creating the final probe (e.g., Cy756-CHN-1).

- Purification & Characterization: Purify the conjugate via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and characterize it using techniques such as 1H NMR and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS).

- In Vitro Validation:

- Cell Culture: Use relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., CAL27, SCC9 for oral cancer, 4T1 for breast cancer).

- Cellular Uptake & Imaging: Incubate cells with the probe (e.g., 1 µM for 2 hours). After washing, image using a confocal microscope with appropriate NIR laser lines and filters.

- Specificity Assays:

- Competitive Inhibition: Pre-treat cells with an excess of unlabeled targeting peptide before adding the fluorescent probe. A significant reduction in fluorescence signal confirms target-specific binding.

- Molecular Modeling & SPR: Validate the binding interaction between the peptide and its target (e.g., DDR-1) using molecular docking simulations and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to determine binding kinetics (K~D~).

- In Vivo Validation:

- Animal Model: Establish subcutaneous or orthotopic tumor models in mice (e.g., using CAL27 or 4T1 cells).

- Imaging: Intravenously inject the probe (e.g., 2 nmol per mouse) and acquire whole-body fluorescence images at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 4, 24, 48 hours) post-injection using a NIR fluorescence imaging system.

- Analysis: Quantify the tumor-to-background ratio (TBR) by measuring mean fluorescence intensity in the tumor region versus a contralateral or adjacent background tissue region. Ex vivo imaging of harvested organs can further confirm biodistribution and tumor specificity.

Protocol: Assessing Performance Metrics in Preclinical Tumor Models

This generalizable protocol highlights critical methodological considerations, particularly the impact of Region of Interest (ROI) selection, as demonstrated in [12].

- Aim: To systematically evaluate the performance metrics (TBR, CNR, AUC) of a fluorescent contrast agent in a pre-clinical brain tumor model, accounting for the effect of ROI selection.

- Animal Model & Imaging:

- Tumor Induction: Establish orthotopic brain tumor models in mice.

- Agent Administration: Inject a non-targeted fluorescent contrast agent (e.g., ICG or a similar dye) intravenously 40 minutes prior to sacrifice.

- Tissue Processing & Imaging: Harvest the brain and image the specimen using high-resolution 3D fluorescence cryotomography.

- Data Analysis & ROI Selection:

- Volume Reconstruction: Reconstruct 3D fluorescence volumes from the cryotomography data.

- Systematic ROI Definition: Define tumor and normal brain ROIs in multiple ways:

- Tumor ROI: The entire tumor volume.

- Background ROIs:

- Contralateral Background: A region in the opposite hemisphere of the brain.

- Adjacent Background: A region immediately adjacent to the tumor boundary.

- Proximal Background: A region closer to the tumor margin.

- Metric Calculation: For each combination of tumor and background ROI, calculate:

- Tumor-to-Background Ratio (TBR): Mean Fluorescence Intensity (Tumor) / Mean Fluorescence Intensity (Background).

- Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR): (Mean Fluorescence Intensity (Tumor) - Mean Fluorescence Intensity (Background)) / Standard Deviation (Background).

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Calculate from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to assess diagnostic performance.

- Key Consideration: The study [12] found that ROI selection drastically affects reported metrics. TBR and CNR can change by a factor of 5-7, and AUC by over 10%, depending on background ROI proximity to the tumor. Future studies must clearly define and justify ROI selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and application of fluorescent probes require a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key solutions for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Fluorescent Probe Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule Fluorophores [9] [10] | Core signaling component of the probe. | Cyanine dyes (Cy5, Cy7, IRDye800CW): NIR emission, modifiable. BODIPY: High quantum yield, photostable. Rhodamine: Stable in acidic environments like lysosomes. |

| Fluorescent Proteins (FPs) [9] [13] | Genetically encoded tags for live-cell protein labeling and interaction studies (FRET). | EGFP: Well-established, but can be bulky. mTFP1: Superior donor for FRET-FLIM due to single-exponential decay. mNeonGreen, mRuby3: Newer FPs with improved brightness and stability. |

| Targeting Ligands | Provide molecular specificity to the probe. | Antibodies (e.g., Trastuzumab): High specificity, but large size. Peptides (e.g., HN-1): Small size, good tissue penetration. Small Molecules (e.g., Folate): Target receptors with high affinity. |

| Self-Labeling Tags & Enzymatic Labeling Systems [9] | Enable site-specific labeling of proteins with synthetic fluorophores in live cells. | HaloTag: Covalently binds to chloroalkane-linked fluorophores. SNAP-tag: Covalently binds to benzylguanine-linked fluorophores. Enzymatic (e.g., Lipoyl Ligase): Uses a short peptide tag for rapid, specific labeling. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Imaging Systems [7] [10] | Detection and quantification of fluorescence signals in vivo. | Fluorescence Cryotomography: High-resolution 3D ex vivo imaging. Whole-Body Small Animal Imagers: For longitudinal in vivo studies. Intraoperative Imaging Systems: For fluorescence-guided surgery applications. |

The architectural design of fluorescent probes is a critical determinant of their performance, dictating specificity, signal strength, and applicability. The comparative data and methodologies presented in this guide underscore a clear trade-off: targeted agents, such as peptide-dye conjugates against DDR-1 or FAP, provide exceptional molecular specificity and high contrast, making them indispensable for probing specific biological pathways. In contrast, non-targeted agents offer a broader, if less specific, utility for initial tumor delineation. The choice between these strategies must be guided by the experimental question, whether it demands molecular-level insight or tissue-level visualization. Furthermore, rigorous and standardized experimental protocols—especially in data analysis steps like ROI selection—are paramount for generating reliable, comparable, and translatable data. As the field advances, the integration of brighter, more photostable NIR fluorophores with highly specific targeting moieties will continue to push the boundaries of sensitivity and resolution in molecular imaging.

Fluorescence sensing mechanisms are fundamental to advancements in biomedical research, environmental monitoring, and drug development. These mechanisms transform molecular recognition events into measurable optical signals, enabling the detection and imaging of biological and chemical analytes with high sensitivity and specificity. Among the most prominent mechanisms are Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET), Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT), and Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE). Each operates on distinct photophysical principles, offering unique advantages and limitations for specific applications. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these four key mechanisms, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select optimal sensing strategies for their specific needs, particularly within the evolving field of targeted versus nontargeted fluorescent agents.

The table below summarizes the core principles, typical signal response, and key performance characteristics of the four fluorescence sensing mechanisms.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Fluorescence Sensing Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Core Principle | Typical Signal Response | Sensitivity | Selectivity Source | Key Advantages | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRET | Distance-dependent energy transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores [14] | Ratiometric (emission shift) [15] | High (nanomolar range) [16] | Spectral overlap and molecular proximity (<10 nm) [14] | Built-in calibration, suitable for biomolecular interaction studies [14] [15] | Requires specific spectral overlap; complex probe design [14] |

| PET | Electron transfer between fluorophore and receptor quenches fluorescence [14] | Turn-On (fluorescence enhancement) [15] | Very High (picomolar to nanomolar) [16] | Receptor-analyze binding interaction [14] | High signal-to-noise ratio, strong background suppression [15] [17] | Single-intensity output, can be susceptible to interference [15] |

| ICT | Redistribution of electron density within a D-π-A system upon excitation [14] [17] | Ratiometric or shift in emission wavelength [16] [17] | High [16] | Analyte-induced change in electron donor/acceptor strength [14] | Large Stokes shift, solvatochromism [17] | Can be sensitive to environmental factors (e.g., pH, polarity) [17] |

| AIE | Restriction of intramolecular motion enables emission in aggregate state [16] [18] | Turn-On (fluorescence enhancement in aggregates) [16] | High [16] | Specific aggregation triggered by analyte [16] | Excellent photostability, outperforms probes with Aggregation-Caused Quenching (ACQ) [18] | Requires specific molecular design to control aggregation [16] |

Detailed Mechanism Analysis and Experimental Protocols

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

FRET is a non-radiative process where an excited donor fluorophore transfers energy to a proximal acceptor fluorophore through dipole-dipole interactions [14].

Key Experimental Protocol: A typical FRET experiment involves co-administering a targeted agent bound to a donor fluorophore and a control (non-targeted) agent bound to an acceptor fluorophore [19]. The binding potential (BP), proportional to target concentration, is quantified using formulas like:

BP = \frac{[Targeted Agent]_{bound}}{[Control Agent]_{bound}}

Accurate quantification requires correction for differences in plasma input functions (PIFs) of the co-administered agents, which can be achieved via techniques like dual-channel pulse-dye densitometry [19].

- Visualization of FRET Mechanism:

Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET)

PET functions through electron transfer from a receptor unit to the excited fluorophore (or vice versa), leading to fluorescence quenching. Upon analyte binding, this electron transfer is suppressed, restoring fluorescence ("turn-on") [14] [17].

- Key Experimental Protocol: PET-based probe performance is highly dependent on the energy levels of the molecular orbitals. A key design principle is to tune the HOMO energy level of the fluorophore to inhibit unwanted proton interference, thereby improving selectivity [15]. Probe response is characterized by measuring the fluorescence enhancement ratio (F/F₀) after exposure to the target analyte, with higher ratios indicating better sensitivity and turn-on response.

- Visualization of PET Mechanism:

Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT)

ICT occurs in a donor-π-acceptor (D-π-A) structured molecule. Upon photoexcitation, electron density is redistributed from the donor to the acceptor group, often resulting in a large Stokes shift and solvatochromism [14] [17].

- Key Experimental Protocol: ICT probe design involves synthesizing a molecule with a strong electron-donating group (e.g., carbazole) linked to a strong electron-withdrawing group. The probe's sensitivity is evaluated by monitoring the spectral shift (often a ratiometric change) in emission upon analyte binding, which alters the push-pull efficiency. A variation, Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer (TICT), relies on restriction of molecular rotation for fluorescence turn-on, providing very low background emission [17].

- Visualization of ICT Mechanism:

Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE)

AIE is a unique phenomenon where fluorogens (AIEgens) are non-emissive in solution but emit strongly in the aggregated or solid state due to the restriction of intramolecular motions (RIM) [16] [18].

- Key Experimental Protocol: A common application is designing an AIEgen that is initially quenched via another mechanism (e.g., FRET). Upon encountering the target analyte (e.g., hypoxia), a specific chemical change (e.g., bond cleavage) disrupts the quenching mechanism and induces aggregation, leading to a strong fluorescence turn-on. The performance is validated by comparing fluorescence intensity in solution versus in aggregates, and in vivo performance is assessed by monitoring tumor accumulation and activation post-intravenous injection [18].

- Visualization of AIE Mechanism:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for developing and working with these fluorescence sensing mechanisms.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Fluorescence Sensing

| Category | Specific Item / Class | Key Function in Research | Relevant Mechanism(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Fluorophores | 1,8-Naphthalimide, Rhodamine, BODIPY, Cyanines (e.g., Cy3, Cy5) [7] [15] | Acts as the signal unit (donor/acceptor) in probe design. | FRET, PET, ICT |

| AIE Luminogens (AIEgens) | Tetraphenylethene (TPE) derivatives [18] | Core unit that becomes emissive upon aggregation, overcoming ACQ. | AIE |

| Recognition Moieties | Boronate ester [15], Azobenzene (Azo) [18] | Provides selectivity by specifically reacting with or binding to the target analyte (e.g., HClO, hypoxic environment). | PET, FRET, AIE |

| Nanomaterial Scaffolds | Quantum Dots (QDs), Carbon Dots (CDs), Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [16] [14] | Enhances delivery, stability, and signal properties of fluorescent probes. Can act as a donor/acceptor. | FRET, PET, AIE |

| Surface Modifiers | DSPE-PEG₂₀₀₀ [18] | Improves biocompatibility, solubility, and circulation time of nano-probes in biological applications. | All (especially in vivo) |

| Targeting Ligands | Antibodies (e.g., Trastuzumab), Affibodies (e.g., ABY-029) [7] [19] | Enables active targeting of specific biomarkers (e.g., HER2 receptors on tumors) for molecular imaging. | All (for targeted agents) |

FRET, PET, ICT, and AIE represent four powerful and distinct sensing mechanisms. The choice of mechanism depends heavily on the specific application requirements, such as the need for rationetric quantification (FRET, ICT), ultra-sensitive turn-on detection (PET, AIE), or operation in aggregate-prone environments (AIE). A emerging and powerful trend is the strategic combination of these mechanisms, such as ICT-FRET [15] or FRET-based off-on AIE systems [18], to engineer probes with superior performance, including lower background, higher specificity, and built-in self-calibration. This synergy, coupled with advancements in nanomaterials and targeting ligands, is pushing the boundaries of sensitivity and specificity in fluorescence sensing, paving the way for more precise research tools and diagnostic agents in drug development.

Biomarker Identification and Validation Strategies

Fluorescence molecular imaging has emerged as a powerful technique in biomedical research and clinical oncology, enabling the visualization of molecular and cellular processes in real-time [7]. This field relies on fluorescent agents that accumulate in target tissues, primarily through two distinct mechanisms: non-targeted agents that exploit passive physiological accumulation, and targeted agents that actively bind to specific molecular biomarkers [20]. The comparative performance of these agent classes directly impacts their effectiveness in biomarker identification and validation, influencing factors such as specificity, signal-to-background ratio, and diagnostic accuracy [1] [21]. As the field of surgical optomics advances—integrating optical imaging with computational analytics—the precision of biomarker validation has significantly improved, turning the operating room into a data-rich environment for surgical decision-making [5]. Understanding the strategic applications and limitations of both targeted and non-targeted approaches provides researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate validation methodologies based on specific research objectives and clinical contexts.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Fluorescent Agents

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Non-Targeted versus Targeted Fluorescent Agents

| Parameter | Non-Targeted Agents | Targeted Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Accumulation | Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect [20] | Specific binding to molecular targets (e.g., receptors, enzymes) [6] [20] |

| Primary Biomarker Basis | Physiological abnormalities (leaky vasculature, poor lymphatic drainage) [21] | Molecular overexpression (e.g., folate receptor, DDR-1, FAP) [6] [11] |

| Typical Tumor-to-Background Ratio | Variable, often lower (qualitative assessment) [5] | Generally higher (e.g., TBR changes by factor of 5 based on ROI selection) [22] |

| Optimal Validation Context | Perfusion assessment, anatomical guidance [5] | Specific biomarker quantification, margin delineation [22] |

| Clinical Translation Stage | Widespread use (ICG, methylene blue) [5] [23] | Limited approvals, mostly in clinical trials (OTL-38, Panitumumab-IRDye800CW) [23] [21] |

| Quantification Capability | Limited by variable pharmacokinetics [5] | More amenable to standardization [22] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Selected Fluorescent Agents in Clinical and Preclinical Studies

| Agent | Type | Molecular Target | Key Performance Metrics | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICG [5] [23] | Non-targeted | Passive EPR accumulation | Reduced anastomotic leak by 4.2% (RR 0.645); NNT 22-23 in colorectal surgery [23] | Clinical (Phase III trials) |

| Cy756-CHN-1 [6] | Targeted (peptide-based) | DDR-1 receptor | Superior fluorescence intensity and tumor affinity in CAL27, SCC9, and 4T1 cell lines [6] | Preclinical (in vivo mouse models) |

| OTL-38 [21] | Targeted (small molecule) | Folate receptor | FDA-approved for ovarian cancer; improved tumor visualization [21] | Clinical (approved agent) |

| FAP-Targeted Probes [11] | Targeted (small molecule) | Fibroblast Activation Protein | Excellent performance for labeling CAF populations in solid tumors [11] | Preclinical (in vivo models) |

| TMR-PEG1k [22] | Non-targeted | Passive EPR accumulation | TBR changed by factor of 5, CNR by factor of 7 depending on background ROI selection [22] | Preclinical (orthotopic brain tumor models) |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

In Vivo Validation of Tumor Targeting Efficiency

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the targeting efficiency and specificity of fluorescent agents in animal models [6] [22].

Materials Required:

- Orthotopic or subcutaneous tumor models (e.g., U87 GFP-expressing glioma cells, CAL27, SCC9, 4T1 cell lines) [6] [22]

- Fluorescent agent of interest (e.g., targeted peptide-fluorophore conjugate)

- Control agents (non-targeted fluorophores, PBS)

- Fluorescence imaging system (e.g., whole-body fluorescence cryotomography, NIRF cameras)

- Image analysis software (e.g., 3D Slicer, ImageJ) [22]

Procedure:

- Administer the fluorescent agent intravenously (e.g., 42.1 nmol for TMR-PEG1k) at a predetermined time before sacrifice (e.g., 40 minutes) [22].

- Euthanize animals and prepare specimens for imaging, maintaining consistent handling conditions across all experimental groups.

- Acquire high-resolution 3D fluorescence volumes using appropriate imaging parameters (e.g., 100μm sectioning for cryotomography) [22].

- Define tumor regions of interest (ROIs) using ground truth markers (e.g., GFP expression, co-registered H&E sections) [22].

- Establish background ROIs using standardized methods (contralateral brain, adjacent regions, whole background) to enable consistent comparison [22].

- Calculate performance metrics including Tumor-to-Background Ratio (TBR), Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR), and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) [22].

- Perform statistical analysis to determine significant differences between targeted and control agents.

Data Interpretation:

- TBR values > 2.0 generally indicate clinically useful contrast [23].

- ROI selection significantly impacts reported metrics; contralateral background ROIs produce more favorable values than peri-tumoral regions [22].

- Comprehensive validation requires comparison across multiple background ROI selection methods to simulate different surgical scenarios [22].

Specificity Validation Through Competitive Binding Assays

Purpose: To confirm molecular targeting specificity and receptor engagement of targeted fluorescent agents [6].

Materials Required:

- Cell lines expressing target receptor (e.g., DDR-1 expressing cancer cells)

- Fluorescently labeled targeted agent (e.g., Cy756-CHN-1)

- Unlabeled competing ligand (e.g., HN-1 peptide)

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence microscopy

- Molecular modeling software (for in silico validation) [6]

Procedure:

- Incubate cells with varying concentrations of targeted fluorescent agent (0-100 nM) for predetermined time periods.

- For competition assays, pre-treat cells with excess unlabeled ligand (10-100x concentration) before adding fluorescent agent.

- Quantify cellular fluorescence intensity using flow cytometry or quantitative fluorescence microscopy.

- Perform saturation binding experiments to determine dissociation constants (Kd) and receptor density.

- Validate binding specificity through molecular modeling and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) if applicable [6].

- Conduct colocalization studies with known receptor markers to confirm target engagement.

Data Interpretation:

- Specific binding demonstrates saturation kinetics with increasing agent concentration.

- Competitive binding shows significant reduction (>70%) in fluorescence signal with unlabeled competitor.

- Successful targeted agents typically show Kd values in nanomolar range for high-affinity binding [6].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Biomarker Identification and Probe Validation Workflow. This diagram outlines the comprehensive pathway from initial biomarker discovery to clinical implementation of fluorescent imaging agents, highlighting key validation checkpoints.

Diagram 2: Molecular Pathways of Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Agent Mechanisms. This diagram compares the distinct biological pathways of targeted and non-targeted fluorescent agents, highlighting differences in specificity and accumulation mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescent Agent Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) [5] [23] | Non-targeted NIR fluorophore for perfusion imaging and anatomical guidance | Clinical standard for anastomosis assessment, tumor delineation [5] |

| Tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) conjugates [22] | Fluorescent label for non-targeted agent development | Validation studies for pharmacokinetics and distribution profiling [22] |

| IRDye800CW [6] [1] | NIR fluorophore for conjugation to targeting ligands | Antibody-fluorophore conjugates (e.g., Panitumumab-IRDye800CW) [6] |

| HN-1 Peptide [6] | Targeting ligand for DDR-1 receptor | Development of tumor-specific imaging agents for multiple cancer types [6] |

| Folate Analogues [21] | Targeting moieties for folate receptor-positive tumors | Clinical agents (e.g., OTL-38/Cytalux) for ovarian and lung cancers [21] |

| Quinolone-Based FAP Inhibitors [11] | Small molecule targeting fibroblast activation protein | Imaging cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor microenvironment [11] |

| U87 GFP-Expressing Glioma Cells [22] | Orthotopic tumor model with intrinsic fluorescent marker | Ground truth determination for fluorescence imaging validation [22] |

The strategic selection between targeted and non-targeted fluorescent agents for biomarker identification and validation depends heavily on the specific research objectives and clinical applications. Non-targeted agents like ICG provide established clinical utility for anatomical guidance and perfusion assessment, with demonstrated efficacy in reducing complications such as anastomotic leaks in colorectal surgery [5] [23]. In contrast, targeted agents offer superior molecular specificity for precise biomarker validation and tumor margin delineation, though their clinical translation remains more limited [6] [21]. The evolving field of surgical optomics continues to enhance quantitative assessment capabilities, addressing current limitations in standardization and quantification [5]. Future advancements in fluorescent probe design, particularly activatable probes and targeted agents with optimized pharmacokinetics, will further refine biomarker validation strategies and expand clinical applications across oncologic, cardiovascular, and inflammatory diseases [1] [21].

Optical Properties and Signal Generation Fundamentals

Fluorescent imaging has become an indispensable tool in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the visualization of biological processes at the molecular level. The fundamental principles governing optical properties and signal generation form the critical foundation for comparing the performance of targeted versus non-targeted fluorescent agents. These agents function by absorbing light at specific wavelengths and re-emitting it at longer wavelengths, a process governed by their distinct photophysical properties and interaction with the biological environment [7] [24].

Targeted fluorescent probes incorporate specific targeting moieties such as antibodies, peptides, or affibodies that bind to biomarkers overexpressed on cancer cells, while non-targeted agents rely on passive accumulation through mechanisms like the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [21]. The strategic design of these agents directly influences their signal generation capabilities, pharmacokinetics, and ultimate diagnostic performance. This comparison guide examines the fundamental optical properties and signal generation mechanisms that differentiate these two classes of fluorescent agents, providing researchers with objective data to inform probe selection and development.

Fundamental Optical Properties of Fluorescent Agents

Photophysical Principles of Fluorescence

The process of fluorescence occurs through a series of photophysical events beginning with photon absorption. When a fluorophore absorbs light energy, its electrons transition from a ground state (S₀) to an excited singlet state (S₁). Following rapid vibrational relaxation, the excited electron returns to the ground state, emitting a photon with lower energy (longer wavelength) than the absorbed photon—a phenomenon known as the Stokes shift [7] [25]. This shift between excitation and emission wavelengths is crucial for effective signal detection as it enables spectral separation of the emitted signal from excitation light.

The efficiency of this process is quantified by several key parameters. The fluorescence quantum yield (Φ) represents the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed, with higher values indicating brighter probes. The extinction coefficient (ε) measures a probe's ability to absorb light at a specific wavelength. Together, these parameters determine the overall brightness of a fluorescent agent (brightness = ε × Φ) [25]. Additionally, the fluorescence lifetime (τ) denotes the average time a molecule remains in the excited state before returning to ground state, which can be leveraged for fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) to distinguish probes from autofluorescence [25].

Table 1: Key Photophysical Properties of Major Fluorophore Classes

| Fluorophore Class | Excitation Range (nm) | Emission Range (nm) | Quantum Yield | Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Dyes (e.g., ICG, TMR) | 650-800 500-600 | 750-850 550-650 | 0.05-0.15 0.3-0.9 | ~120,000 ~80,000 | Clinical FGS, perfusion imaging Cell tracking, receptor targeting |

| Targeted Probes (e.g., OTL38, ABY-029) | 750-780 600-650 | 790-810 650-700 | 0.10-0.15 0.2-0.4 | ~100,000 ~70,000 | Tumor margin delineation EGFR-positive tumor detection |

| TADF Materials (e.g., 4CzIPN, AI-Cz) | 350-500 | 450-650 | 0.6-0.9 | ~50,000-100,000 | Time-gated imaging, FLIM, organelle tracking |

| BODIPY Dyes | 450-650 | 500-700 | >0.8 | ~80,000 | Cellular imaging, targeted cancer imaging |

Advanced Signal Generation Mechanisms

Beyond conventional fluorescence, several advanced signal generation mechanisms enhance imaging capabilities:

Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence (TADF): TADF materials leverage a small energy gap (ΔEₛₜ) between singlet and triplet states to facilitate reverse intersystem crossing (RISC), enabling triplet excitons to upconvert to singlet states and emit delayed fluorescence [25]. This mechanism yields exceptionally long-lived emission (microseconds to milliseconds) that permits time-gated detection, effectively suppressing short-lived background autofluorescence (typically 1-10 ns) and significantly improving signal-to-noise ratio [25].

Activatable Probes: These "smart" probes remain quenched until activated by specific tumor microenvironment biomarkers such as enzymes (e.g., γ-glutamyltranspeptidase, aminopeptidase N), pH variations, or reactive oxygen species [21] [26]. Activation mechanisms include enzyme-mediated cleavage of quenching groups, pH-dependent conformational changes, or biomarker-induced chemical transformations that restore fluorescence. This design dramatically improves target-to-background ratios compared to always-on probes [21].

Multimodal and Multifunctional Probes: Advanced probes now incorporate capabilities for simultaneous imaging and therapy. For example, probe A-H integrates methylene blue and rhodamine 6G components, enabling concurrent detection of ATP and HClO biomarkers while providing photodynamic therapy (PDT) capabilities [26]. Such designs represent the convergence of diagnostic and therapeutic functions within a single molecular platform.

Comparative Performance: Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Agents

Signal Generation and Performance Metrics

The fundamental difference between targeted and non-targeted fluorescent agents lies in their mechanism of tissue accumulation and retention. Non-targeted agents such as indocyanine green (ICG) and tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated PEG (TMR-PEG1k) primarily rely on the EPR effect for passive tumor accumulation, where leaky tumor vasculature permits extravasation and retention of circulating agents [21] [22]. In contrast, targeted agents employ molecular recognition elements—including antibodies, affibodies, or peptides—that actively bind to specific cell surface receptors overexpressed in pathological tissues [21] [27].

This distinction in accumulation mechanisms directly impacts critical performance metrics, particularly tumor-to-background ratio (TBR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), which determine the practical utility of these agents for fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) [22]. Recent systematic evaluations have demonstrated that region of interest (ROI) selection significantly influences reported performance metrics, with background regions adjacent to tumor boundaries yielding more clinically relevant TBR and CNR values compared to contralateral background regions [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Fluorescent Agents

| Performance Metric | Non-Targeted Agents | Targeted Agents | Experimental Conditions | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor-to-Background Ratio (TBR) | 1.5-2.5 (TMR-PEG1k in glioma models) | 2.5-4.5 (ABY-029 in sarcoma) | Orthotopic mouse glioma model Phase 0/1 clinical trial, dose escalation | Factor of 5 change based on ROI selection [22] High correlation with EGFR expression [27] |

| Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) | 2.8-5.5 (Varies with background ROI proximity) | Not specifically reported | Cryotomography in murine models, systematic ROI analysis | Factor of 7 change based on background selection [22] |

| Time to Peak Fluorescence | 40 min - 3 hr (Varies with agent and model) | 1-6 hr (Varies with targeting moiety) | Preclinical models, intravenous administration | Non-targeted agents generally demonstrate faster kinetics |

| Signal Specificity | Moderate (Limited by EPR effect heterogeneity) | High (Molecular recognition reduces background) | Multiple cancer models, receptor overexpression | Targeted agents significantly reduce false positives [21] [28] |

| Diagnostic Sensitivity | 65-85% (In vivo LNM detection) | 70-100% (Ex vivo LNM detection) | Clinical studies, lymph node metastasis detection | Postoperative FI shows superior sensitivity [28] |

| Diagnostic Specificity | 75-90% (In vivo LNM detection) | 66-100% (Ex vivo LNM detection) | Clinical studies, lymph node metastasis detection | Higher specificity in formalin-fixed tissues [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

Orthotopic Tumor Model Imaging Protocol

Objective: Systematically evaluate TBR and CNR of fluorescent agents while controlling for region of interest selection variables [22].

Materials and Methods:

- Animal Models: 7-10 week old female nude mice with U87 GFP-expressing orthotopic gliomas [22]

- Imaging Agent: TMR-PEG1k (non-targeted) administered via tail vein injection (42.1 nmol) 40 minutes prior to sacrifice [22]

- Imaging System: Whole-body 3D fluorescence cryotomography with:

- 530 nm LED excitation (550 nm short pass filter) for TMR-PEG1k

- 470 nm LED excitation (475 nm short pass filter) for GFP

- Emission filters: 620-650 nm for TMR, 510-530 nm for GFP [22]

- Image Analysis:

- Tumor boundaries determined from GFP fluorescence with H&E validation

- Multiple background ROIs defined: whole brain, contralateral, adjacent, near margin

- TBR calculated as mean tumor fluorescence intensity divided by mean background intensity

- CNR calculated as (mean tumor intensity - mean background intensity)/noise standard deviation [22]

Key Findings: Background ROI selection dramatically impacts performance metrics, with TBR varying by a factor of 5 and CNR by a factor of 7 depending on background region proximity to tumor [22].

Clinical Trial Protocol for Targeted Agent Evaluation

Objective: Determine optimal dosing and imaging parameters for targeted fluorescent agents in human subjects [27].

Study Design: Phase 0/1 dose-escalation trial of ABY-029 (anti-EGFR affibody) in soft-tissue sarcoma patients [27].

Methodology:

- Patient Population: 12 soft-tissue sarcoma patients with EGFR-positive tumors [27]

- Dosing Regimen: Microdose followed by escalation to 3× and 6× microdose levels [27]

- Imaging Protocol:

- Administration of ABY-029 prior to surgery

- Intraoperative imaging with compatible fluorescence imaging systems

- Correlation of fluorescence with EGFR expression via histopathology [27]

- Outcome Measures:

- TBR calculation from intraoperative imaging

- Correlation coefficient between fluorescence intensity and EGFR expression

- Optimal dose determination for maximal TBR with minimal background [27]

Key Findings: ABY-029 achieved performance comparable to antibody-based agents with significantly reduced time between imaging and surgical resection, demonstrating the advantage of synthetic affibody peptides for intraoperative imaging [27].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Molecular Activation Pathways of Fluorescent Probes

Diagram 1: Probe Activation Pathways in Tumors

Experimental Workflow for Agent Evaluation

Diagram 2: Experimental Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Fluorescence Imaging Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | ICG, Methylene Blue, TMR-PEG1k, ABY-029, OTL-38 | Signal generation for tumor visualization, receptor targeting | Varying excitation/emission profiles, binding affinity, clearance rates |

| Targeting Moieties | Anti-EGFR affibody, Folate, Trastuzumab, SGM-101 | Molecular recognition of tumor-specific biomarkers | High binding affinity, specificity, modular conjugation capability |

| Imaging Systems | Whole-body 3D cryotomography, NIR fluorescence cameras, Confocal microscopes | Detection and quantification of fluorescence signals | Sensitivity, resolution, wavelength compatibility, quantification capability |

| Animal Models | U87 GFP-expressing gliomas, Orthotopic tumor models, Patient-derived xenografts | Preclinical evaluation of probe performance | Tumor microenvironment representation, biomarker expression, clinical relevance |

| Analysis Software | 3D Slicer, ImageJ, MATLAB, Custom ROI analysis tools | Image processing, quantification, and performance metric calculation | ROI definition, intensity measurement, statistical analysis, visualization |

| Histopathology Tools | H&E staining, Immunofluorescence, Antibodies for biomarker validation | Ground truth establishment and correlation with fluorescence | Tissue structure preservation, biomarker detection, correlation capability |

The comparative analysis of optical properties and signal generation fundamentals reveals a complex tradeoff between targeted and non-targeted fluorescent agents. Non-targeted agents offer practical advantages of simpler design, faster clinical translation, and more predictable pharmacokinetics, while targeted agents provide superior specificity and potential for higher TBR through molecular recognition. The emerging generation of activatable probes represents a promising middle ground, combining the signal-to-noise advantages of targeted agents with the broader applicability of non-targeted approaches.

Performance metrics, particularly TBR and CNR, remain highly dependent on methodological factors including ROI selection, imaging timing, and dose optimization. The development of standardized evaluation protocols, as demonstrated in recent systematic studies, will be crucial for objective comparison between agent classes. Future directions will likely focus on multimodal agents that combine complementary targeting strategies, along with continued refinement of TADF materials and quantitative imaging systems to overcome current limitations in penetration depth and quantification accuracy.

Advanced Applications and Imaging Methodologies in Research and Medicine

Non-Targeted Agents in Perfusion Assessment and Structure Delineation

Fluorescence imaging has emerged as a powerful technique for real-time visualization of biological processes, playing an increasingly important role in surgical navigation and cancer research [1] [29]. Within this field, a fundamental distinction exists between targeted agents, which bind to specific molecular biomarkers, and non-targeted agents, which accumulate in tissues based on physiological characteristics such as enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, perfusion dynamics, and vascular abnormalities [1] [30].

Non-targeted fluorescent agents, including indocyanine green (ICG), fluorescein, and methylene blue, offer distinct advantages for perfusion assessment and structural delineation. These clinically approved agents provide rapid visualization of vascular architecture and tissue viability without requiring specific molecular targets [31] [29]. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of non-targeted agents against targeted alternatives, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison: Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Agents

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics based on current research findings:

Table 1: Performance comparison between targeted and non-targeted fluorescent agents

| Parameter | Non-Targeted Agents | Targeted Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Translation Status | Multiple agents FDA-approved (ICG, fluorescein, methylene blue) [29] | Mostly in preclinical or early clinical trials [1] |

| Imaging Timeline | Immediate to minutes post-injection [31] | Hours to days post-injection (wait for background clearance) [31] |

| Contrast Mechanism | Passive accumulation via EPR effect, perfusion kinetics [31] [1] | Active binding to specific molecular targets [1] [30] |

| Delineation Specificity | Distinguishes tissue types via perfusion differences [31] | Identifies specific molecular pathways [30] |

| Application in Multifocal Tumor Detection | Demonstrated capability using dynamic imaging [31] | Theoretical potential, limited by target expression heterogeneity |

| Quantitative Performance (TBR) | Variable (1.5-5×) depending on ROI selection [22] | Potentially higher but agent-dependent [22] |

Table 2: Experimental performance metrics of non-targeted agents in tumor delineation

| Agent | Sensitivity | Specificity | Tumor-to-Background Ratio | Study Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cypate | 0.97 | 0.75 | Not specified | Murine mammary cancer model [31] |

| LS288 | 0.85 | 0.81 | Not specified | Murine mammary cancer model [31] |

| TMR-PEG1k | Not specified | Not specified | Variable (1.5-5×) depending on background ROI selection [22] | Orthotopic brain tumor model [22] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Imaging

Principle and Workflow: Dynamic fluorescence imaging harnesses differences in perfusion kinetics to visualize structural characteristics of different tissues [31]. The method involves continuous imaging following contrast agent administration, capturing the temporal changes in fluorescence intensity that reflect perfusion patterns, circulation, dye kinetics, and molecular interactions [31].

Detailed Protocol:

- Animal Model Preparation: Establish multifocal tumor models (e.g., bilateral mammary fat pad injections in nude mice) [31]

- Imaging System Setup: Use cooled CCD camera with appropriate filters (e.g., 830±10 nm BP filter for NIR imaging); set frame rate to 1.3 frames/sec with 400 msec exposure time [31]

- Dye Administration: Prepare dye solutions (e.g., 100 μM in PBS with 20% DMSO); inject 100 μL via tail vein catheter, accounting for catheter dead space [31]

- Image Acquisition: Capture data for approximately 10-20 minutes post-injection under anesthetic maintenance [31]

- Data Processing: Import image sequences into MATLAB; generate time-intensity curves; apply clustering algorithms to identify tissues with similar perfusion properties [31]

Region of Interest Selection Considerations

Critical Methodology Note: Background ROI selection significantly impacts reported performance metrics. Studies show TBR can vary by a factor of 5 and CNR by a factor of 7 depending on background ROI proximity to tumor boundaries [22]. Contralateral background ROIs typically produce more favorable metrics than peri-tumoral regions [22].

Mechanism of Action: Signaling Pathways and Physiological Processes

Non-targeted agents operate through fundamentally different mechanisms compared to targeted approaches:

Key Physiological Processes:

- Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect: Tumor vessels exhibit enhanced permeability due to structural abnormalities, allowing macromolecules and nanoparticles to extravasate and accumulate in tumor tissue [30]

- Altered Perfusion Kinetics: Tumor vasculature demonstrates characteristic perfusion patterns distinguishable from normal tissue through dynamic imaging [31]

- Vascular Density Variations: Histological analysis suggests vasculature in connective tissue surrounding tumors contributes significantly to identification via perfusion imaging [31]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for non-targeted perfusion imaging

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Targeted NIR Dyes | Cypate, LS288 [31] | Perfusion kinetics studies, multifocal tumor detection | Hydrophobic (cypate) vs. hydrophilic (LS288) properties affect distribution [31] |

| Clinical Agents | Indocyanine Green (ICG), Methylene Blue, Fluorescein [29] | Translational studies, clinical correlation | FDA-approved, established safety profiles [29] |

| Animal Models | Orthotopic 4T1-Luc (murine mammary), HT1080 (human fibrosarcoma) [31] | Tumor model development | Bilateral implantation for multifocal studies [31] |

| Imaging Equipment | Cooled CCD cameras, NIR filters, LED illumination [31] | Signal detection and processing | 760 nm excitation, 830 nm emission filters [31] |

| Analysis Software | MATLAB, 3D Slicer [31] [22] | Data processing, 3D visualization | Custom algorithms for time-intensity analysis [31] |

Emerging Alternatives and Complementary Technologies

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI)

HSI has emerged as a promising, non-contact, non-invasive modality that requires no contrast agents [32]. This technology captures spatial and spectral information to assess tissue oxygenation, hemoglobin distribution, and perfusion characteristics [32]. Recent advances demonstrate HSI applications in laparoscopic surgeries, brain tumor delineation, and head and neck cancer interventions [32].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Standardized assessment remains challenging for non-targeted analysis methods. The Benchmarking and Publications for Non-Targeted Analysis Working Group (BP4NTA) has developed frameworks to address terminology harmonization, performance metrics, and reporting practices [33]. These efforts aim to improve reproducibility and inter-study comparisons in non-targeted imaging research.

Non-targeted fluorescent agents provide valuable tools for perfusion assessment and structural delineation in oncological research and clinical applications. While offering advantages in clinical translation speed and imaging timelines, they demonstrate different performance characteristics compared to targeted agents, particularly in specificity and quantitative metrics. The continued development of dynamic imaging approaches, standardized evaluation methods, and complementary technologies like hyperspectral imaging will further enhance the research utility and clinical application of non-targeted agents for tissue delineation and functional assessment.

The evolution of molecular imaging has been significantly advanced by the development of receptor-targeted probes, which offer superior specificity compared to non-targeted agents. These probes are engineered to bind with high affinity to specific cell surface receptors that are overexpressed in diseased tissues, particularly in cancer. This guide provides a comparative analysis of fluorescent probes targeting three critically important receptor classes: integrins, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2), and Ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EphA2). The focus on these targets stems from their well-established roles in tumor progression, angiogenesis, and metastasis, making them ideal for diagnostic imaging and therapeutic monitoring. While non-targeted fluorescent agents like indocyanine green (ICG) provide valuable anatomical and perfusion information, they lack the molecular specificity required for precise lesion characterization and margin delineation. Targeted optical fluorescence imaging represents a rapidly advancing field that is progressively transitioning from preclinical research to clinical application, especially in oncology, by leveraging the specific binding of carrier molecules (antibodies, peptides, or small molecules) conjugated to fluorescent dyes to disease biomarkers [1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of probes targeting integrins, HER2, and EphA2, providing structured experimental data and methodologies to inform research and development decisions.

Performance Comparison of Receptor-Targeted Probes

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and clinical development status for probes targeting integrins, HER2, and EphA2. Data is synthesized from preclinical and clinical studies to enable direct comparison of their operational characteristics and translational potential.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Receptor-Targeted Probes

| Target Receptor | Probe/Ligand Example | Affinity (Kd) | Emission Wavelength | Key Applications | Imaging Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrins | αvβ3-targeted RGD peptides | Variable (nM-μM range) | NIR-I (700-900 nm) | Angiogenesis imaging, tumor detection | Broad applicability, multiple targeting strategies |

| HER2 | Trastuzumab-IRDye800CW | ~0.1-1 nM (antibody-dependent) | ~800 nm | Breast & gastric cancer surgery guidance | High specificity, clinical validation of target |

| EphA2 | EPH-3-DBS peptide | 13.1 nM (peptide) | NIR-I & NIR-II (790-900 nm) | Colorectal cancer, glioblastoma imaging | NIR-II capability, large Stokes shift (>130 nm) |

Table 2: Clinical Translation Status and Limitations

| Target Receptor | Clinical Translation Stage | Key Limitations | Tumor Specificity | Penetration Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrins | Proof of concept/early clinical | Moderate affinity, heterogeneous expression | Moderate | Limited by NIR-I (~1 cm) |

| HER2 | Advanced clinical trials | Limited to HER2-positive cancers | High (in HER2+ tumors) | Limited by NIR-I (~1 cm) |

| EphA2 | Preclinical/early development | Optimal ligand validation ongoing | High in overexpression | Enhanced by NIR-II (several cm) |

Experimental Protocols for Probe Evaluation

EphA2-Targeted Probe Development and Validation

The development of EPH-3-DBS, an EphA2-targeted NIR-I/II fluorescent probe, exemplifies a standardized approach for evaluating receptor-specific imaging agents [34].

Synthesis and Conjugation:

- The asymmetric donor-acceptor-donor (D-A-D) fluorophore (DBS) is synthesized based on a cyanine scaffold, providing bright NIR-I/NIR-II emission, large Stokes shift (>130 nm), and improved water solubility.

- The high-affinity EphA2-targeting peptide EPH-3 (Tyr-HYP-Thr-[d]-Ser-Glu-HYP) is conjugated to the DBS fluorophore via solid-phase synthesis and purified using preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

- Mass spectrometric characterization confirms successful probe synthesis and purity.

Affinity and Specificity Assessment:

- Cell Culture: Utilize EphA2-positive HCT116 colorectal cancer cells and other relevant cell lines (e.g., U87 MG for glioblastoma).

- Binding Assay: Incubate cells with varying concentrations of EPH-3-DBS (e.g., 0-200 nM) for predetermined time points (typically 30-120 minutes) at 37°C.

- Competitive Inhibition: Pre-treat cells with excess unlabeled EPH-3 peptide (100-fold molar excess) to confirm receptor-mediated binding.

- Quantification: Measure cell-associated fluorescence using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. Calculate dissociation constant (Kd) using saturation binding curves and nonlinear regression analysis.

In Vivo Imaging Protocol:

- Animal Models: Establish subcutaneous xenograft, orthotopic colon cancer, and liver metastasis models in immunodeficient mice using EphA2-expressing cancer cells.

- Probe Administration: Inject EPH-3-DBS intravenously (dose range: 1-5 mg/kg) via tail vein.

- Image Acquisition: Perform sequential fluorescence imaging at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24 hours post-injection) using NIR-I and NIR-II imaging systems.

- Ex Vivo Validation: Sacrifice animals at endpoint, collect and image major organs and tumors to quantify biodistribution (%ID/g). Confirm EphA2 expression in tumor tissues via immunohistochemistry.

HER2-Targeted Probe Evaluation

HER2-targeted probes, typically antibody-based, require specific validation methodologies [1] [35].

Probe Design and Validation:

- Conjugate HER2-specific antibodies (e.g., trastuzumab) or antibody fragments with NIR fluorophores (e.g., IRDye800CW, Cy5.5).

- Validate binding specificity using HER2-overexpressing cell lines (e.g., SK-BR-3, BT-474) versus HER2-negative controls (e.g., MCF-7).

- Perform internalization assays to confirm probe uptake, a critical feature for signal amplification and potential therapeutic delivery.

In Vivo Specificity Assessment:

- Utilize HER2-positive and HER2-negative xenograft models in parallel to confirm target-specific accumulation.

- Administer the fluorescent probe intravenously and monitor tumor-to-background ratios over time.

- Conduct blocking studies with unlabeled antibody to demonstrate competitive inhibition of signal.

Integrin-Targeted Probe Testing

Integrin-targeted probes, typically using RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) peptide motifs, follow a distinct evaluation pathway [36].

Binding Assay Protocol:

- Utilize αvβ3 integrin-positive cell lines (e.g., U87 MG glioblastoma, HUVECs).

- Perform fluorescence-based binding assays with increasing probe concentrations.

- Include function-blocking integrin antibodies to confirm specificity.

In Vivo Angiogenesis Imaging:

- Administer integrin-targeted probes to tumor-bearing mice.

- Exploit the predominant expression of αvβ3 integrin on tumor neovasculature for specific targeting.

- Correlate fluorescence signal with immunohistochemical analysis of CD31 and integrin expression.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Understanding the molecular pathways associated with each target receptor provides crucial context for probe design and interpretation of imaging results.

EphA2 Receptor Signaling

EphA2 mediates diverse cellular functions through both canonical (ligand-dependent) and non-canonical (ligand-independent) signaling pathways [37]. The receptor structure comprises an extracellular region with a ligand-binding domain (LBD), cysteine-rich domain, and two fibronectin type III repeats, a transmembrane helix, and an intracellular region containing a juxtamembrane region, tyrosine kinase domain, sterile alpha motif (SAM), and a PDZ-binding motif [37].

EphA2 Signaling Pathways: This diagram illustrates the two primary signaling modes of the EphA2 receptor. Canonical ligand-dependent signaling (right) leads to adhesion repulsion, while non-canonical ligand-independent signaling (left) promotes migration and invasion [37].