Validating Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging: A Quantitative Framework for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) provides unparalleled quantitative insights into cellular metabolism, protein interactions, and drug efficacy by measuring the nanosecond-scale persistence of fluorophores in an excited state.

Validating Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging: A Quantitative Framework for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) provides unparalleled quantitative insights into cellular metabolism, protein interactions, and drug efficacy by measuring the nanosecond-scale persistence of fluorophores in an excited state. This article offers a comprehensive framework for validating FLIM as a robust quantitative tool, moving from foundational principles to advanced applications. We explore the core advantages of lifetime over intensity-based measurements, detail cutting-edge methodologies and instrumentation for high-speed data acquisition, and address critical challenges like noise, autofluorescence, and data analysis. By presenting rigorous validation strategies and comparative analyses with emerging computational techniques like deep learning, this guide empowers researchers and drug development professionals to harness the full potential of quantitative FLIM for preclinical studies and clinical translation.

The Quantitative Advantage: Why Fluorescence Lifetime Outshines Intensity

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) is rapidly transforming quantitative cellular imaging by providing measurements independent of fluorescence intensity, which are often compromised by experimental artifacts. This review establishes the core principles of fluorescence lifetime through the Jablonski diagram framework and validates its quantitative advantages for biomedical research. We present a comparative analysis of intensity-based versus lifetime-based imaging methodologies, detailing experimental protocols for implementing FLIM across diverse biological systems. Recent breakthroughs in genetically encoded fluorescence lifetime indicators and computational simulation tools are examined for their ability to accurately quantify metabolic and signaling molecules in live cells and tissues. The integration of FLIM with advanced analysis techniques creates a powerful platform for investigating disease mechanisms, cellular heterogeneity, and therapeutic efficacy, positioning fluorescence lifetime as an essential quantitative parameter in modern biological research.

Fluorescence microscopy provides indispensable molecular contrast for biomedical research, yet traditional intensity-based measurements face significant challenges for quantitative analysis. Variations in fluorophore concentration, excitation light intensity, photobleaching, and focus drift introduce artifacts that hamper reliable quantification [1]. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) addresses these limitations by measuring the average time a fluorophore remains in an excited state before emitting a photon, typically on the nanosecond timescale [2] [3]. This parameter is intrinsic to each fluorophore and largely independent of concentration, making it ideally suited for quantitative imaging.

The validation of fluorescence lifetime for quantitative measurement research represents a critical advancement for studying dynamic cellular processes. Unlike intensity-based signals, fluorescence lifetime provides absolute measurements that enable direct comparison across experiments, timepoints, and laboratory settings [4] [5]. This review establishes the fundamental principles of fluorescence lifetime through the framework of the Jablonski diagram, compares methodological approaches for FLIM implementation, details experimental protocols for quantitative applications, and examines emerging technologies that expand FLIM's capabilities for drug development and clinical research.

Core Principles: The Jablonski Diagram and Fluorescence Lifetime

The Jablonski Diagram: Energy State Transitions

The Jablonski diagram, developed by Polish physicist Aleksander Jablonski, provides a schematic representation of the electronic energy states and transitions that occur during fluorescence phenomena [6] [7]. This diagram organizes energy vertically, with horizontal lines representing distinct electronic states (S0, S1, S2, etc.) and vibrational energy levels within each electronic state.

The fluorescence process begins when a photon of appropriate energy excites a molecule from its ground electronic state (S0) to a higher electronic excited state (S1, S2,...). This absorbance transition occurs on an extremely fast timescale (approximately 10-15 seconds) [7]. Following excitation, the molecule rapidly undergoes vibrational relaxation and internal conversion to the lowest vibrational level of the first excited electronic state (S1) through non-radiative energy loss to the environment. Fluorescence emission then occurs as the molecule returns from the S1 state to the ground state, emitting a photon with longer wavelength (lower energy) than the excitation photon - a phenomenon known as the Stokes shift [6] [2].

Defining Fluorescence Lifetime

Fluorescence lifetime (τ) is defined as the average time a fluorophore remains in the excited state before returning to the ground state [2]. Mathematically, for a population of excited molecules, the fluorescence intensity decay follows first-order kinetics:

I(t) = I₀e^(-t/τ)

where I(t) is the intensity at time t, I₀ is the initial intensity after excitation, and τ is the fluorescence lifetime [2]. The lifetime represents the time required for the fluorescence intensity to decay to 1/e (approximately 36.8%) of its initial value. This parameter depends on the fluorophore's molecular structure and its immediate environment, including factors such as pH, ion concentration, temperature, and molecular interactions [6] [3].

Table 1: Fluorescence Lifetimes of Selected Biological Fluorophores

| Fluorophore | Lifetime (ns) | Excitation (nm) | Emission (nm) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H (free) | 0.4 | 340 | 470 | Cellular metabolism |

| NAD(P)H (bound) | 1.0-5.0 | 340 | 470 | Cellular metabolism |

| FAD | 2.3-2.9 | 450 | 535 | Cellular metabolism |

| Collagen | 1.2-4.0 | 360-400 | 400-500 | Tissue structure |

| GFP | 2.6-3.0 | 488 | 507 | Protein tagging |

| qMaLioffG (-ATP) | ~2.9 | 512 | 525 | ATP sensing |

| qMaLioffG (+ATP) | ~1.8 | 512 | 525 | ATP sensing |

Methodological Comparison: Intensity-Based vs. Lifetime-Based Imaging

Limitations of Intensity-Based Fluorescence Measurements

Conventional intensity-based fluorescence measurements face several challenges for quantitative biological imaging:

- Concentration Dependence: Signal intensity scales with fluorophore concentration, making it difficult to distinguish between changes in molecular concentration versus environmental effects [1].

- Experimental Artifacts: Variations in excitation source intensity, microscope alignment, sample thickness, and focus drift introduce measurement errors [1] [3].

- Photobleaching: Irreversible fluorophore degradation during imaging causes signal loss that confounds quantitative measurements over time [1].

- Spectral Crosstalk: In multicolor experiments, overlapping emission spectra complicate signal separation and quantification [3].

Even ratiometric intensity measurements, which use two emission channels to normalize for concentration effects, remain vulnerable to variations in microscope settings that hamper reproducibility between laboratories [1].

Advantages of Fluorescence Lifetime Measurements

FLIM overcomes these limitations by exploiting the temporal characteristics of fluorescence:

- Concentration Independence: Fluorescence lifetime is largely independent of fluorophore concentration, enabling direct comparison between samples with different expression levels [4] [5] [3].

- Environmental Sensitivity: Lifetime measurements detect molecular environment changes (pH, ion concentration, binding interactions) that intensity measurements may miss [2] [3].

- Reduced Artifact Susceptibility: Lifetime is minimally affected by excitation intensity variations, photobleaching (within limits), and focus drift [1].

- Multiple Parameter Resolution: FLIM can distinguish multiple fluorescent species with overlapping spectra based on their distinct lifetimes [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Intensity-Based vs. Lifetime-Based Imaging Approaches

| Characteristic | Intensity-Based Imaging | Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Accuracy | Limited by artifacts | High, due to environmental sensitivity |

| Concentration Dependence | Strong | Minimal |

| Photobleaching Sensitivity | High | Moderate |

| Experimental Reproducibility | Variable between systems | High between systems |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited by spectral overlap | Enhanced by lifetime contrast |

| Technical Complexity | Low | High |

| Measurement Speed | Fast | Moderate to slow |

| Photon Efficiency | High | Moderate |

| Environmental Sensing | Limited | Excellent |

| Instrument Cost | Low to moderate | High |

FLIM Implementation Methodologies

FLIM can be implemented through two primary technical approaches:

Time-Domain FLIM: The sample is excited with short laser pulses, and the fluorescence decay is measured directly by recording photon arrival times relative to the excitation pulse [2] [3]. Common implementations include time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) and gated detection.

Frequency-Domain FLIM: The sample is excited with intensity-modulated light, and the phase shift and demodulation of the fluorescence signal relative to the excitation are measured to calculate lifetime [2].

Each approach offers distinct advantages: time-domain provides direct lifetime visualization and handles complex multi-exponential decays well, while frequency-domain typically enables faster data acquisition [2].

Experimental Validation: Quantitative FLIM Applications

ATP Quantification with qMaLioffG Sensor

Recent breakthroughs in genetically encoded biosensors have dramatically expanded FLIM's quantitative capabilities. The qMaLioffG indicator represents a significant advancement for ATP measurement, addressing a fundamental metabolite in cellular energy metabolism [8] [1].

Sensor Design and Mechanism: qMaLioffG was developed by engineering a single green fluorescent protein with an inserted bacterial FoF1-ATP synthase ε subunit as the ATP-binding domain [1]. Upon ATP binding, conformational changes alter the chromophore environment, producing a substantial fluorescence lifetime shift (Δτ = 1.1 ns) within physiologically relevant ATP concentrations (Kd = 2.0 mM at room temperature, 11.4 mM at 37°C) [1]. This dynamic range exceeds conventional FRET-FLIM indicators (typically 0.1-0.6 ns) [1].

Experimental Protocol for ATP Imaging:

- Cell Preparation: Culture cells expressing qMaLioffG (cytoplasmic or mitochondrial targeted) on imaging-appropriate dishes.

- FLIM Acquisition: Image using a confocal microscope equipped with FLIM capability and 488 nm or 512 nm excitation.

- Lifetime Calculation: Apply fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) to measure lifetime values pixel-by-pixel.

- Calibration Curve: Generate a calibration curve by measuring fluorescence lifetime in permeabilized cells with defined ATP concentrations.

- Quantitative Analysis: Convert lifetime values to ATP concentrations using the calibration curve [1].

Biological Applications: Researchers have applied qMaLioffG to quantify ATP distribution heterogeneity in various model systems. In HeLa cell spheroids, FLIM revealed spatial gradients of ATP levels reflecting metabolic heterogeneity [1]. Studies of patient-derived fibroblasts with DNM1L mutations demonstrated significantly reduced mitochondrial ATP levels, illustrating FLIM's capability to detect pathological metabolic alterations [1]. In mouse embryonic stem cells, qMaLioffG detected higher cytoplasmic ATP levels in naïve pluripotent cells maintained with 2i/LIF compared to primed states, revealing metabolic reprogramming during pluripotency regulation [1].

Addressing FLIM Limitations with FLiSimBA

While FLIM offers significant advantages for quantitative imaging, real-world biological applications face challenges including autofluorescence, background signals, and instrumentation artifacts that can compromise lifetime measurements [4] [5]. The recently developed FLiSimBA (Fluorescence Lifetime Simulation for Biological Applications) framework addresses these limitations by providing a computational tool for simulating realistic FLIM data.

FLiSimBA Simulation Approach:

- Signal Components: Models four key contributors: sensor fluorescence, tissue autofluorescence, PMT afterpulse, and background signals [4] [5].

- Photon Sampling: Generates realistic lifetime histograms by sampling from ideal sensor lifetime distributions convolved with instrument response functions [5].

- Noise Incorporation: Adds experimentally determined autofluorescence and background parameters to create biologically relevant noise conditions [4] [5].

Experimental Design Optimization: FLiSimBA enables researchers to determine minimum photon requirements for detecting lifetime differences, establish error estimates for measurements, and define expression level thresholds where lifetime remains insensitive to concentration variations [4] [5]. This computational framework supports rigorous experimental design and accurate data interpretation by quantifying how factors like autofluorescence impact the apparent fluorescence lifetime in biological systems [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Quantitative FLIM

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| qMaLioffG | Genetically encoded ATP indicator | ATP quantification in cytoplasm and mitochondria | 1.1 ns lifetime dynamic range, 488 nm excitation [8] [1] |

| FLIM-AKAR | FRET-based kinase activity reporter | PKA signaling dynamics in brain slices | Double exponential decay, activity-dependent lifetime changes [4] [5] |

| FLiSimBA Software | FLIM simulation framework | Experimental design optimization | MATLAB/Python implementation, models biological noise [4] [5] |

| Sodium Fluoride (NaF) | Glycolysis inhibitor | ATP depletion experiments | Enolase inhibition, reduces cytoplasmic ATP [1] |

| Oligomycin | OXPHOS inhibitor | Mitochondrial ATP production assessment | ATP synthase inhibition, reduces mitochondrial ATP [1] |

| NAD(P)H | Endogenous metabolic fluorophore | Cellular metabolism monitoring | Lifetime changes with protein binding [2] |

| FAD | Endogenous metabolic fluorophore | Oxidative metabolism assessment | Shorter lifetime when protein-bound [2] |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The integration of fluorescence lifetime measurements with advanced biosensors and computational analysis represents a powerful platform for quantitative biological research. Future developments will likely focus on expanding the palette of FLIM-compatible biosensors, particularly those compatible with conventional 488 nm laser systems [1]. Additionally, combining FLIM with deep learning approaches enhances data analysis capabilities, enabling automated classification of cancer types [9] and extraction of subtle metabolic signatures from complex tissue environments.

Technical advancements in FLIM instrumentation continue to address current limitations in acquisition speed and photon efficiency [2] [9]. The establishment of annual Quantitative Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (QFLIM) meetings highlights the growing importance of this methodology and provides a venue for disseminating new developments [10]. As these technologies mature and become more accessible, fluorescence lifetime imaging is poised to become an indispensable tool for drug development, clinical diagnostics, and fundamental biological research.

The validation of fluorescence lifetime as a quantitative parameter through the framework of the Jablonski diagram provides researchers with a powerful approach to overcome the limitations of intensity-based imaging. By implementing the experimental protocols and methodologies detailed in this review, scientists can leverage the full potential of FLIM for precise, reproducible quantitative measurements in complex biological systems.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) is increasingly recognized as a transformative quantitative tool in biomedical research and drug development. Unlike intensity-based fluorescence measurements, FLIM provides a robust, self-referencing readout that remains unaffected by common experimental variables that typically compromise quantitative accuracy. This guide systematically evaluates FLIM's core advantages—specifically its independence from fluorophore concentration, photobleaching, and excitation intensity fluctuations—against traditional intensity-based methods. Through experimental data and protocol details, we demonstrate how these properties establish FLIM as a superior technique for quantifying molecular interactions, cellular metabolism, and microenvironmental parameters in living systems.

Fluorescence lifetime refers to the average time a fluorophore remains in its excited state before returning to the ground state, typically occurring on the nanosecond timescale [2] [11]. This parameter is an intrinsic molecular property that depends primarily on the fluorophore's immediate molecular environment, including factors like pH, ion concentration, viscosity, and molecular binding events [2]. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) generates spatial maps of this lifetime parameter, providing a quantitative dimension beyond what traditional intensity-based fluorescence microscopy can offer.

The fundamental distinction between FLIM and intensity-based approaches lies in their relationship to common experimental variables. While fluorescence intensity depends directly on fluorophore concentration, excitation light intensity, and can be drastically affected by photobleaching, fluorescence lifetime remains largely independent of these factors [12]. This independence forms the basis of FLIM's superior quantitative capabilities, particularly for applications requiring precise measurement of molecular interactions and microenvironmental parameters in living cells and tissues.

Core Advantages: Comparative Analysis

The quantitative superiority of FLIM emerges from its fundamental independence from three key experimental variables that routinely compromise intensity-based measurements.

Independence from Fluorophore Concentration

In intensity-based fluorescence measurements, signal strength correlates directly with fluorophore concentration, making it difficult to distinguish between changes in molecular environment and changes in the number of fluorescent molecules. FLIM overcomes this limitation because fluorescence lifetime is an intrinsic property of the fluorophore in its specific microenvironment.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis: Concentration Independence

| Aspect | Intensity-Based Imaging | FLIM |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Signal proportional to number of fluorophores | Decay rate independent of fluorophore number |

| Quantitative Impact | Cannot distinguish environment from concentration | Direct readout of molecular environment regardless of concentration |

| Experimental Consequence | Requires careful control of expression/loading levels | Enables comparison across samples with variable expression |

| FRET Applications | Requires correction for donor concentration | Direct measurement via donor lifetime alone [12] |

The concentration-independent nature of FLIM is particularly valuable in biological systems where controlling exact expression levels of fluorescent proteins or maintaining precise concentrations of exogenous dyes is challenging. This property enables meaningful quantitative comparisons across different cells, tissue regions, or experimental conditions where fluorophore concentration may vary significantly.

Resistance to Photobleaching Effects

Photobleaching presents a major challenge in time-lapse imaging, as it causes a continuous decline in fluorescence intensity that can be misinterpreted as biological phenomena. Since fluorescence lifetime is largely unaffected by photobleaching until very late stages, FLIM provides more reliable data in longitudinal experiments.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis: Photobleaching Resistance

| Aspect | Intensity-Based Imaging | FLIM |

|---|---|---|

| Photobleaching Effect | Progressive signal loss | Lifetime largely unaffected until severe bleaching |

| Quantitative Impact | Declining intensity confounds quantification | Stable lifetime measurements throughout time series |

| Data Integrity | Compromised over extended imaging | Maintained across acquisition period |

| Corrective Measures | Complex normalization required | Minimal correction needed |

This bleaching resistance is especially beneficial for extended live-cell imaging, where maintaining quantitative accuracy throughout the experiment is crucial. While the absolute number of fluorescent molecules decreases during photobleaching, the lifetime of the remaining intact fluorophores remains unchanged, allowing FLIM to provide consistent environmental readouts even as overall intensity declines [12].

Variations in laser power, illumination field homogeneity, and light path characteristics create significant challenges for quantitative intensity measurements. FLIM effectively bypasses these issues because the measured lifetime is independent of the excitation intensity, provided sufficient photons are detected for accurate lifetime determination.

Experimental data from FLIM-FRET studies demonstrates this advantage clearly. In protein-protein interaction studies using FRET, FLIM can quantify interaction strengths without requiring careful adjustment of laser power across samples, a necessity for intensity-based FRET measurements [12]. This independence also makes FLIM more robust for clinical translation, where controlling illumination conditions precisely may be challenging.

Experimental Validation and Protocols

FLIM-FRET for Protein-Protein Interactions

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) measured via FLIM provides a powerful method for quantifying molecular interactions, leveraging FLIM's concentration independence.

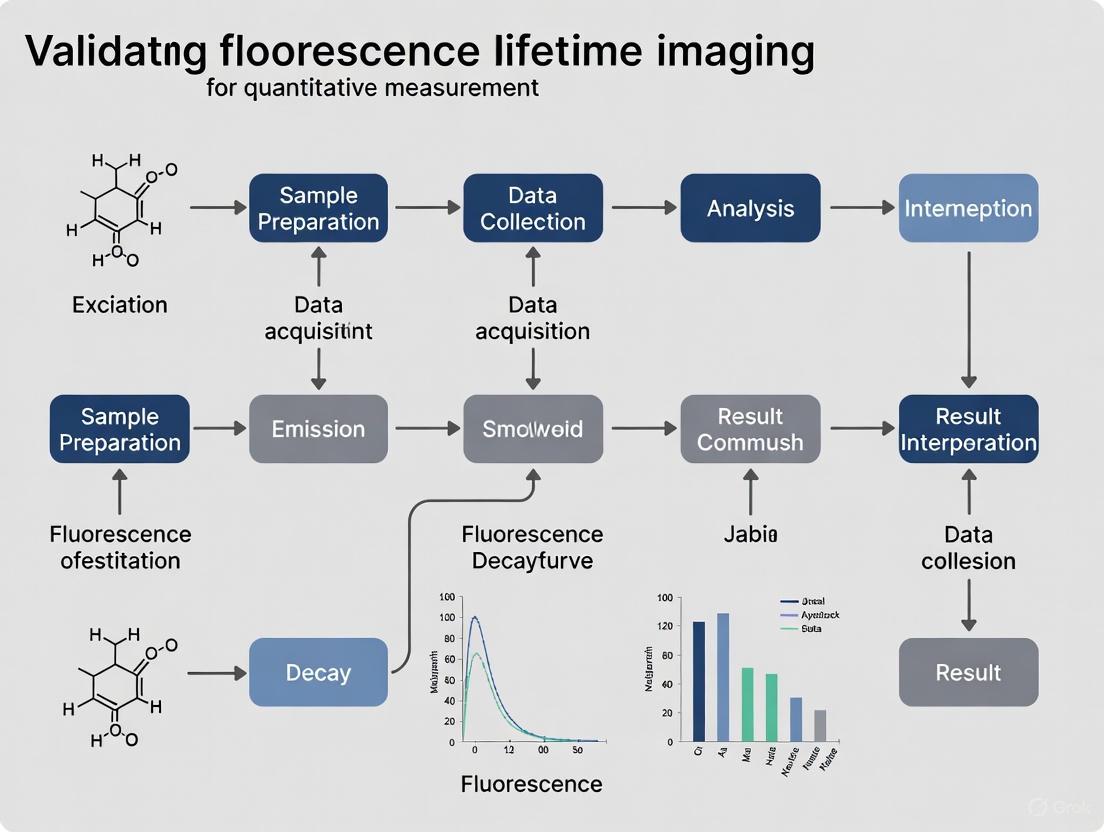

Diagram: FLIM-FRET Experimental Workflow for quantifying protein-protein interactions via donor fluorescence lifetime changes.

Experimental Protocol: FLIM-FRET

- Reference Measurement: Determine the donor fluorescence lifetime (τ) in a donor-only control sample using FLIM acquisition [12].

- FRET Sample Measurement: Measure the donor lifetime (τ_quench) in the experimental sample containing both donor and acceptor fluorophores.

- FRET Efficiency Calculation: Calculate FRET efficiency using the formula: E = 1 - (τ_quench/τ) [12].

- Distance Calculation: For known FRET pairs, convert efficiency to intermolecular distance using the Förster equation: E = 1/[1 + (r/R₀)⁶], where r is the distance and R₀ is the Förster radius [12].

This approach eliminates the need for complex corrections for donor concentration, acceptor concentration, and excitation intensity that plague intensity-based FRET methods [12]. The direct measurement of donor lifetime reduction provides a more reliable quantification of molecular interactions.

Metabolic Imaging via NADH/FAD Autofluorescence

FLIM of endogenous fluorophores enables label-free metabolic imaging, particularly using the metabolic coenzymes NAD(P)H and FAD.

Experimental Protocol: Metabolic FLIM

- Sample Preparation: Cells or tissues require no fluorescent labeling, leveraging inherent autofluorescence [2].

- Two-Photon Excitation: Typically using 740 nm for NAD(P)H and 890 nm for FAD to minimize photodamage [2].

- Lifetime Data Acquisition: Collect time-domain or frequency-domain FLIM data using appropriate detectors (PMTs or SPAD arrays).

- Lifetime Component Analysis: Fit decay curves to extract short and long lifetime components corresponding to free and protein-bound states of coenzymes.

- Metabolic Index Calculation: Compute the fluorescence lifetime-derived redox ratio: FLIM-Redox Ratio = (FAD fluorescence lifetime)/(NAD(P)H fluorescence lifetime).

This label-free approach enables non-invasive monitoring of cellular metabolic states in living samples, with applications ranging from cancer research to neurodegenerative disease studies. The concentration independence is particularly valuable as endogenous fluorophore levels can vary significantly between cells and conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FLIM

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Fluorophores | NAD(P)H, FAD, Collagen | Label-free metabolic and structural imaging [2] |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | FRET-based PKA/Akt sensors, GFP variants | Monitoring specific signaling pathways and molecular interactions [13] |

| Synthetic Dyes | Coumarin-6, Rhodamine derivatives | Environmental sensing (pH, viscosity, ions) with lifetime sensitivity [14] [15] |

| FLIM-FRET Pairs | CFP-YFP, GFP-RFP | Quantifying protein-protein interactions and conformational changes [12] [16] |

| Reference Standards | Coumarin-6 (τ ≈ 2.5 ns) | System calibration and lifetime validation [15] |

Technological Implementation

Modern FLIM systems typically employ one of two primary technical approaches, each with distinct advantages for quantitative imaging:

Time-Domain FLIM

- Utilizes pulsed lasers (ti:sapphire, diode) with pulse widths of picoseconds or femtoseconds

- Employs time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) or gated detection

- Builds fluorescence decay histograms pixel-by-pixel for precise lifetime determination [2] [16]

Frequency-Domain FLIM

- Uses intensity-modulated continuous-wave lasers or high-repetition-rate pulsed lasers

- Measures phase shift and demodulation of fluorescence relative to excitation

- Enables faster acquisition suitable for dynamic live-cell imaging [2]

Both approaches successfully decouple lifetime information from intensity variations, achieving the fundamental quantitative advantages described in this guide. Current technological advances are making FLIM more accessible through integrated commercial systems, miniaturized components, and improved data analysis workflows.

FLIM represents a paradigm shift in quantitative fluorescence microscopy, addressing fundamental limitations of intensity-based approaches. Its independence from fluorophore concentration, photobleaching, and excitation intensity fluctuations provides a robust foundation for reliable quantification of molecular interactions, metabolic states, and microenvironmental parameters in living systems. As FLIM technology continues to evolve toward more user-friendly implementations and standardized analysis protocols, its adoption is poised to expand significantly across biological research and drug development. The experimental data and protocols presented in this guide provide a foundation for researchers to leverage FLIM's unique advantages in their quantitative imaging studies.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) has emerged as a transformative analytical technique in biomedical research, enabling quantitative measurement of cellular metabolism and tissue microenvironment through label-free detection of endogenous fluorophores. Unlike intensity-based fluorescence methods, FLIM measures the exponential decay rate of fluorescence emission following excitation, providing a robust parameter that is independent of fluorophore concentration, excitation light intensity, and photobleaching [8] [1]. This quantitative capability makes FLIM particularly valuable for investigating the metabolic reprogramming associated with disease states, particularly cancer, where altered cellular energetics serve as a hallmark of pathogenesis [17] [18].

The primary endogenous fluorophores exploited for quantitative metabolic imaging include the metabolic co-enzymes NAD(P)H (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) and FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide), along with structural proteins such as collagen. These molecules provide intrinsic contrast without requiring exogenous labeling, allowing non-invasive assessment of cellular function in living tissues and engineered disease models [19] [20]. NAD(P)H functions as a key electron carrier in glycolytic pathways and cellular redox reactions, while FAD serves as a crucial component in the electron transport chain for oxidative phosphorylation [17] [19]. Collagen, the most abundant protein in the extracellular matrix, provides structural support and its organization reflects tissue remodeling in various pathological conditions [19].

The fluorescence lifetimes of these endogenous fluorophores are exquisitely sensitive to their molecular environment and protein-binding status. For NAD(P)H, the protein-bound state (associated with enzymatic activity) exhibits a longer fluorescence lifetime (~1-6 ns) compared to the free state (~0.4 ns) [20]. Conversely, for FAD, the protein-bound state displays a shorter lifetime (~0.2-2 ns) compared to the free state (~2.8 ns) [20]. These lifetime differences enable FLIM to quantify the relative proportions of free and protein-bound species, providing insights into cellular metabolic activity that correlate with conventional metabolic assays [18] [20]. The integration of FLIM with advanced computational analysis, including phasor analysis and deep learning approaches, has further enhanced its capability to resolve subtle metabolic heterogeneity within complex tissue architectures [21] [14].

Metabolic Pathways and Biomarker Significance

NAD(P)H and FAD in Cellular Energetics

The metabolic co-factors NAD(P)H and FAD serve as central regulators of cellular energy production and redox homeostasis. NAD(P)H exists in both phosphorylated (NADPH) and non-phosphorylated (NADH) forms, with NADH primarily involved in ATP production through glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, while NADPH functions as a key reducing agent for antioxidant defense and biosynthetic pathways [20]. In the glycolytic pathway, glucose is converted to pyruvate with concomitant reduction of NAD+ to NADH. Subsequently, during the citric acid cycle, additional NADH molecules are generated along with the reduction of FAD to FADH2. These reducing equivalents then fuel the electron transport chain, where oxidative phosphorylation generates the majority of cellular ATP [17].

The relative balance between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation is frequently altered in pathological conditions, most notably in cancer. The "Warburg effect" describes the propensity of many cancer cells to favor glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation even in normoxic conditions [17] [18]. This metabolic reprogramming results in characteristic changes in the levels and binding states of NAD(P)H and FAD that can be quantified through FLIM. Specifically, a shift toward glycolysis typically corresponds with increased free NAD(P)H and a higher free/bound ratio, while increased oxidative phosphorylation is associated with greater protein-bound NAD(P)H [18] [20]. The fluorescence lifetime of NAD(P)H has been shown to positively correlate with cellular oxygen consumption rate, confirming its utility as a biomarker for mitochondrial function [20].

The redox ratio, calculated as the intensity ratio of NAD(P)H to FAD or their respective lifetime parameters, provides a quantitative measure of the cellular metabolic state [19]. However, researchers must exercise caution when comparing studies, as different formulations of this ratio exist in the literature (e.g., NAD(P)H/FAD, FAD/NAD(P)H, or NAD(P)H/[NAD(P)H+FAD]) [19]. The FLIM-derived redox ratio (FLIRR), based on the relative proportions of bound NAD(P)H to bound FAD, has emerged as a promising optical biomarker, with higher values typically indicative of a shift toward oxidative phosphorylation and lower values associated with enhanced glycolysis [18].

Collagen in Tissue Structure and Disease

Collagen represents the most abundant autofluorescent protein in the extracellular matrix and serves as a critical structural component in connective tissues. Its fluorescence properties differ from those of metabolic co-factors, with emission primarily in the blue-green spectrum when excited by ultraviolet light [19]. Beyond its structural role, collagen organization and content are increasingly recognized as important biomarkers in various pathological processes, including cancer progression, fibrosis, and tissue regeneration.

In cancer research, collagen deposition and alignment have been correlated with tumor progression and metastatic potential. The tumor microenvironment often exhibits characteristic collagen reorganization, with increased density and straightened fibers facilitating cancer cell invasion [18]. In stem cell research and regenerative medicine, collagen production serves as a key indicator of differentiation, particularly in chondrogenesis where mesenchymal stem cells generate collagen-rich extracellular matrix resembling cartilage [19]. Multispectral autofluorescence imaging enables simultaneous monitoring of collagen alongside metabolic co-factors, providing complementary information about tissue structure and cellular function within the same sample [19].

Table 1: Key Endogenous Fluorophores and Their Characteristics

| Fluorophore | Primary Function | Excitation/Emission Maxima | Free Lifetime | Bound Lifetime | Key Metabolic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H | Metabolic co-factor, electron carrier | ~350-740 nm/~450-470 nm | ~0.4 ns [20] | ~1-6 ns [20] | Glycolytic activity, redox state |

| FAD | Metabolic co-factor, electron transport | ~450 nm/~535 nm | ~2.8 ns [20] | ~0.2-2 ns [20] | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| Collagen | Structural extracellular matrix protein | ~325-370 nm/~400-465 nm | N/A | N/A | Tissue architecture, fibrosis, differentiation |

Signaling Pathways Involving Endogenous Fluorophores

The diagram below illustrates the interconnected metabolic pathways involving NAD(P)H and FAD, and how their fluorescence properties provide readouts of cellular metabolism.

Quantitative Comparison of FLIM Biomarkers

FLIM provides multiple quantitative parameters for assessing cellular metabolism and tissue microenvironment. The table below summarizes key FLIM-derived metrics for NAD(P)H, FAD, and collagen, along with their reported changes in various experimental models.

Table 2: Quantitative FLIM Parameters of Endogenous Fluorophores in Experimental Models

| Experimental Model | Fluorophore | Key FLIM Parameters | Reported Changes | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer spheroids (MDA-MB-231) [18] | NAD(P)H | τm (mean lifetime), α1/α2 (fraction free/bound) | Migrating cells: ↑ bound NAD(P)H fraction | Metabolic shift toward OXPHOS in invading cells |

| Breast cancer spheroids (MDA-MB-231) [18] | FAD | τm (mean lifetime), α1/α2 (fraction free/bound) | Migrating cells: ↑ bound FAD fraction | Metabolic shift toward OXPHOS in invading cells |

| Breast cancer spheroids (MDA-MB-231) [18] | NAD(P)H & FAD | FLIRR (Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Redox Ratio) | Higher collagen density: ↑ FLIRR | ECM stiffness promotes OXPHOS |

| Reconstructed human skin (UVA exposure) [20] | NAD(P)H | fB (bound fraction) | Post-UVA: ↑ bound NAD(P)H in fibroblasts | Oxidative stress response |

| Reconstructed human skin (UVA exposure) [20] | FAD | fB (bound fraction) | Post-UVA: ↓ bound FAD in keratinocytes | Dose-dependent oxidative damage |

| MSC differentiation [19] | Collagen | Intensity, Spectral signature | Chondrogenesis: ↑ collagen intensity | Extracellular matrix production |

| MSC differentiation [19] | NAD(P)H & FAD | Redox Ratio (NAD(P)H/FAD) | Adipogenesis: initial ↑ then ↓ redox ratio | Dynamic metabolic shifts during differentiation |

| Mouse breast cancer model [17] | NAD(P)H | Intensity, Lifetime | Tumor regions: ↑ intensity & ↑ lifetime | Altered metabolism in carcinoma |

The quantitative data reveal several consistent trends across experimental models. In cancer systems, tumor cells frequently display increased NAD(P)H intensity and longer fluorescence lifetime compared to normal adjacent tissue [17]. The FLIRR metric has proven particularly valuable for identifying spatial metabolic heterogeneity within tumor spheroids, with migrating cells at the invasive front exhibiting higher FLIRR values consistent with increased oxidative phosphorylation [18]. In stem cell differentiation, chondrogenic induction leads to increased collagen production detectable through autofluorescence intensity, while adipogenic differentiation produces characteristic temporal changes in the redox ratio [19].

Environmental stressors, such as UVA exposure, trigger cell-type-specific metabolic responses measurable through FLIM. Fibroblasts in reconstructed human skin demonstrate increased bound NAD(P)H fraction following UVA exposure, indicating an oxidative stress response, while keratinocytes show a dose-dependent decrease in bound FAD fraction [20]. These findings highlight the sensitivity of FLIM parameters to both intrinsic metabolic reprogramming and extrinsic environmental challenges.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

FLIM Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

FLIM systems for endogenous fluorophore imaging typically utilize multiphoton excitation with mode-locked Ti:Sapphire lasers (tuning range ~700-1000 nm) to achieve sufficient penetration depth in tissue samples and minimize photodamage [17] [18]. For simultaneous NAD(P)H and FAD imaging, wavelength mixing approaches have been developed where two synchronous femtosecond laser beams (e.g., 760 nm and 1045 nm) are temporally overlapped to create a virtual two-photon excitation wavelength (e.g., 880 nm) that efficiently excites both fluorophores [20]. This strategy enables independent control of NAD(P)H and FAD signal levels while ensuring all fluorescence originates from the same diffraction-limited focal volume [20].

Fluorescence lifetime detection is typically accomplished through time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) systems, which provide high temporal resolution for recording fluorescence decay curves [17] [20]. The instrument response function (IRF) of the optical system should be measured (typically using second harmonic generation from a β-BaB2O4 crystal) to account for system limitations in lifetime calculations [17]. For spectral separation of autofluorescence signals, systems may incorporate spectral detectors (e.g., 16-channel photomultiplier tubes) covering emission ranges from 350-720 nm [17]. During imaging, samples should be maintained in physiological conditions using temperature and CO₂-controlled chambers to preserve viability, particularly for longitudinal studies [20].

Sample Preparation Protocols

Tissue Section Preparation: For ex vivo tissue imaging, samples are typically fixed in formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned using standard histopathological techniques [17]. Sections may be de-paraffinized and maintained unstained or stained with histological dyes like eosin. Mounting with appropriate media and coverslipping follows standard protocols. For NAD(P)H and FAD imaging, unstained sections are preferred to avoid interference from exogenous fluorophores [17].

3D Cell Culture Models: Tumor spheroids can be generated by seeding cells (approximately 1×10³ cells/well) in ultra-low attachment plates with addition of extracellular matrix components like Matrigel (2.5% v/v) and allowing 48 hours for spheroid formation [18]. Individual spheroids are then embedded in collagen gels at desired concentrations (e.g., 1 mg/ml vs. 4 mg/ml to mimic low and high-density ECM) within specialized chambers like polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) wells created in glass-bottom dishes [18].

Reconstructed Human Skin: Tissue-engineered skin models containing differentiated epidermis and dermal fibroblasts embedded in collagen matrix can be used for metabolic studies. These are typically reconstructed over 12-14 days of differentiation before imaging [20].

Data Processing and Analysis Methods

Phasor Analysis: This fit-free approach transforms FLIM data into Fourier space, mapping per-pixel intensity decay onto orthogonal vectors [20] [14]. The phasor plot allows graphical determination of free and bound fluorophore fractions by measuring the distance of experimental pixels from reference positions of free NAD(P)H and free FAD. This method facilitates visualization of metabolic clusters and reduces computational load compared to exponential fitting [20].

Noise-Reduction Techniques: Fluorescence lifetime data, particularly from autofluorophores with weak signals, often benefits from noise reduction algorithms. Recent advances include noise-corrected principal component analysis (NC-PCA), which selectively identifies and removes noise while preserving biological signals [14]. This approach has demonstrated up to 5.5-fold decrease in uncertainty and over 50-fold reduction in data loss compared to conventional thresholding methods [14].

Lifetime Calculation: Fluorescence decay curves are typically fitted with multi-exponential models using specialized software to extract lifetime components (τ₁, τ₂) and their relative amplitudes (α₁, α₂). The mean lifetime (τm) can be calculated as τm = α₁τ₁ + α₂τ₂ [18]. For NAD(P)H, the bound fraction (fB) is often represented by α₂, while for FAD, the bound fraction is represented by α₁ [20].

The diagram below illustrates a typical workflow for FLIM experiments, from sample preparation to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful FLIM investigation of endogenous fluorophores requires specific reagents, instrumentation, and analysis tools. The table below summarizes key components of the research toolkit for quantitative FLIM studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Endogenous Fluorophore FLIM

| Category | Specific Product/Model | Key Features | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy Systems | Custom multiphoton workstation [17] | Ti:Sapphire mode-locked laser (~700-1000 nm), TCSPC electronics | Enables deep tissue imaging with sub-micron resolution |

| Detection Systems | Becker & Hickl SPC-830 [17] | Time-correlated single photon counting | High temporal resolution for fluorescence decay recording |

| Spectral Detectors | Hamamatsu PML-16 PMT [17] | 16-channel, detection range 350-720 nm | Spectral unmixing of autofluorescence signals |

| Cell Culture Models | MCF-10A, MDA-MB-231 [18] | Normal and cancerous breast epithelial lines | Well-characterized models for cancer metabolism studies |

| 3D Culture Systems | Ultra-low attachment plates [18] | Spheroid formation with Matrigel support | Recapitulates tumor microenvironment heterogeneity |

| Extracellular Matrix | Rat tail collagen I [18] | Tunable concentration (1-4 mg/ml) | Mimics physiological and stiffened tissue environments |

| Tissue Models | Reconstructed human skin (T-Skin) [20] | Contains epidermis and dermis with living fibroblasts | Suitable for UV exposure studies and dermatological research |

| Analysis Software | Phasor analysis algorithms [20] [14] | Fit-free approach for lifetime calculation | User-friendly visualization of metabolic clusters |

| Advanced Analytics | NC-PCA denoising [14] | Noise-corrected principal component analysis | Enhances signal fidelity in low-photon-count data |

Comparative Performance and Applications

Biomarker Performance Across Disease Models

The diagnostic performance of endogenous fluorophores varies across disease models and experimental conditions. In cancer detection, NAD(P)H and FAD FLIM parameters have demonstrated high sensitivity for discriminating transformed from normal tissue. In mouse models of breast cancer, carcinoma regions exhibited significantly higher NAD(P)H intensity and longer fluorescence lifetime compared to adjacent normal tissue [17]. Similarly, in 3D breast cancer spheroids, migrating cells displayed characteristic FLIM signatures consistent with metabolic shifts toward oxidative phosphorylation, particularly in high-density collagen environments [18].

In stem cell research, multispectral autofluorescence imaging of NAD(P)H, FAD, and collagen has enabled non-invasive monitoring of differentiation dynamics over extended time periods (21 days) without compromising cell viability [19]. Chondrogenic differentiation produced increased collagen levels, while adipogenic differentiation showed characteristic temporal patterns in the redox ratio. However, researchers caution against assuming consistent metabolic shifts during differentiation, as the relationship between metabolic programming and lineage specification appears context-dependent [19].

For environmental stress assessment, FLIM of endogenous fluorophores has proven valuable in quantifying oxidative damage in skin models. Following UVA exposure, NAD(P)H and FAD biomarkers demonstrated unique temporal dynamics and cell-type-specific sensitivity, with fibroblasts responding more prominently to NAD(P)H lifetime changes and keratinocytes showing dose-dependent FAD alterations [20]. These findings highlight the importance of multi-parameter FLIM assessment across different cell types within complex tissues.

Advantages Over Conventional Methods

FLIM of endogenous fluorophores offers several advantages over traditional analytical methods for assessing cellular metabolism. Compared to immunohistochemical approaches for protein expression analysis, FLIM provides functional information about metabolic activity rather than mere molecular presence [22]. Unlike bulk metabolic assays (e.g., Seahorse extracellular flux analysis), FLIM preserves spatial information at subcellular resolution, enabling investigation of metabolic heterogeneity within tissues and 3D models [18].

The label-free nature of autofluorescence imaging eliminates potential artifacts introduced by exogenous dyes or fluorescent proteins, which can themselves alter cellular metabolism [20]. Furthermore, FLIM parameters are inherently quantitative and less susceptible to variations in fluorophore concentration, excitation intensity, and detection efficiency compared to intensity-based measurements [1]. This quantitative reliability facilitates direct comparison between experiments and laboratories when standardized protocols are implemented.

Recent technological advances have further enhanced FLIM capabilities. The integration of deep learning approaches has improved image analysis speed and accuracy, enabling automated classification of metabolic states and identification of subtle patterns that may escape manual analysis [21]. Additionally, the development of novel fluorescence lifetime-based indicators, such as qMaLioffG for ATP imaging, expands the range of metabolic parameters that can be quantified alongside endogenous fluorophores [8] [1].

FLIM of endogenous fluorophores represents a powerful methodology for quantitative assessment of cellular metabolism and tissue microenvironment in various physiological and pathological contexts. The metabolic co-factors NAD(P)H and FAD provide sensitive indicators of energetic and redox states, while collagen serves as a marker of extracellular matrix remodeling. The quantitative parameters derived from FLIM, including fluorescence lifetimes, free/bound fractions, and redox ratios, offer unique insights into metabolic reprogramming associated with disease processes such as cancer, stem cell differentiation, and environmental stress responses.

The continuing evolution of FLIM technology, including improved instrumentation, advanced data processing algorithms, and integration with complementary imaging modalities, promises to further enhance our understanding of metabolic regulation in complex biological systems. As standardization and accessibility of FLIM methodologies improve, clinical translation of these approaches for diagnostic applications and therapeutic monitoring appears increasingly feasible. The quantitative nature, label-free implementation, and spatial resolution of FLIM position it as an indispensable tool in the expanding toolkit for metabolic research and precision medicine.

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) is a powerful physical phenomenon that serves as a "molecular ruler" for quantifying biomolecular interactions and microenvironmental parameters. FRET involves the non-radiative transfer of energy from an excited donor fluorophore to a nearby acceptor fluorophore through dipole-dipole interactions [23] [24]. This energy transfer is highly dependent on the distance between the fluorophores, typically occurring within 1-10 nanometers, making it exquisitely sensitive to molecular-scale changes [24] [25]. The efficiency of FRET (E) follows an inverse sixth-power relationship with the distance (r) between donor and acceptor: E = 1/[1 + (r/R₀)⁶], where R₀ is the Förster radius representing the distance at which energy transfer efficiency is 50% [24] [26]. This fundamental distance dependence enables researchers to precisely monitor dynamic changes in protein conformations, protein-protein interactions, and localized microenvironmental conditions in real-time within living systems [23] [24].

FRET biosensors have emerged as indispensable tools in modern biological research, particularly for applications requiring high spatiotemporal resolution. Unlike traditional biochemical methods such as co-immunoprecipitation, yeast two-hybrid assays, or pull-down assays, FRET biosensors enable non-invasive monitoring of molecular events in live cells with exceptional precision [25]. These sensors can detect instant mechanotransduction processes that occur within seconds, revealing cell-to-cell variability that would be masked in ensemble measurements [27] [24]. The versatility of FRET biosensors extends to diverse applications including cellular imaging, drug discovery, pathogen detection, and cancer diagnosis, establishing them as foundational tools for advancing quantitative measurement research in biomedical sciences [26].

FRET Biosensor Design and Variants

Fundamental Architecture and Engineering Principles

The architecture of FRET biosensors typically incorporates several key domains organized into a single polypeptide chain. A standard design includes: (1) a donor fluorophore, (2) a sensing domain that responds to the target analyte or molecular event, (3) an acceptor fluorophore, and (4) specialized linker regions that connect these components [24] [28]. The strategic engineering of these linkers is particularly crucial for biosensor performance. Recent advancements have introduced rigid, helical ER/K linkers—comprised of alternating repeats of four glutamate residues and four arginines or lysines—which form extended α-helices with hinge-like properties [28]. These structured linkers significantly enhance dynamic range by properly separating affinity binding domains and FRET partners in the unbound state, thereby reducing baseline FRET signals [26] [28]. The length and composition of these linkers directly impact the biosensor's dynamic range, with longer ER/K linkers (up to 30 nm) demonstrating substantial improvements in signal response [28].

The performance of FRET biosensors is quantified through several key parameters. The dynamic range refers to the maximum observable signal difference between active and inactive states, while gain represents the percentage change in FRET ratio following stimulation [24]. Sensitivity is defined as the concentration of stimulants that increases the FRET ratio to 50% of the dynamic range [24]. Optimizing these parameters often requires empirical testing of various geometries, including alterations in linker length, fluorophore selection, and domain organization [28]. Single-chain biosensor designs maintain a 1:1 ratio of donors to acceptors, simplifying FRET imaging and data analysis while ensuring consistent stoichiometry [28].

Advanced FRET Modalities and Their Applications

Recent technological advancements have expanded the FRET toolbox beyond conventional intensity-based measurements, enabling more sophisticated quantitative applications:

FLIM-FRET (Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy-FRET): This technique measures the fluorescence decay rate of the donor fluorophore, which decreases when FRET occurs. FLIM-FRET provides quantitative measurements independent of fluorophore concentration, excitation light intensity, or focus drift, making it particularly valuable for precise quantification [29] [1] [22]. For example, the qMaLioffG ATP indicator exploits FLIM-FRET to enable quantitative imaging of ATP levels in living cells by converting ATP concentration into measurable fluorescence lifetime changes [29] [1].

smFRET (Single-Molecule FRET): This approach detects FRET at the level of individual molecules, revealing conformational heterogeneities and transient intermediate states that are obscured in ensemble measurements [25] [26]. smFRET has been particularly valuable for studying RNA structural dynamics, where it guides the selection of 3D structures consistent with experimental distance constraints [30].

TR-FRET (Time-Resolved FRET): Utilizing long-lifetime probes such as lanthanide chelates with time-gated detection, TR-FRET effectively eliminates background fluorescence, significantly enhancing detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets [25] [28]. This approach enables robust screening protocols for protein-protein interaction modulators even at low protein concentrations [25].

FCCS-FRET (Fluorescence Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy FRET): This technique enables quantitative analysis of molecular interactions in live cells by monitoring the correlated diffusion of two fluorescently labeled molecules within a femtoliter-scale observation volume [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced FRET Modalities

| Technique | Key Principle | Spatial Resolution | Key Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLIM-FRET | Measures donor fluorescence lifetime decay | Subcellular | Quantitative metabolite imaging (e.g., ATP), protein interaction studies [29] [1] [22] | Independent of fluorophore concentration; minimizes artifacts from cellular morphology [1] |

| smFRET | Detects FRET at individual molecule level | Single-molecule | RNA conformational dynamics, protein folding, molecular mechanisms [25] [30] | Reveals heterogeneities and transient states; high temporal resolution [30] |

| TR-FRET | Uses long-lifetime probes with time-gated detection | Molecular | High-throughput screening, PPI modulator identification [25] [28] | Eliminates background; enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance targets [25] |

| FCCS-FRET | Monitors correlated diffusion of labeled molecules | Single-molecule in live cells | Protein complex formation in live cells [25] | Quantitative analysis in physiological environments [25] |

Quantitative Comparison of FRET Biosensor Performance

Performance Metrics Across Biosensor Designs

The quantitative performance of FRET biosensors varies significantly based on their design specifications, fluorophore pairs, and target applications. Systematic engineering approaches have yielded substantial improvements in dynamic range, sensitivity, and reliability. For instance, in the development of Rac1 biosensors, incorporation of ER/K helical linkers of varying lengths (10 nm, 20 nm, and 30 nm) demonstrated a direct correlation between linker length and dynamic range in LRET-based sensors, with the 30 nm linker achieving an exceptional 1100% increase in dynamic range [28]. In contrast, conventional FRET biosensors with fluorescent protein pairs showed more modest but still significant improvements of up to 125% with ER/K linkers compared to unstructured linkers [28].

The choice of fluorophore pairs profoundly impacts biosensor performance. The CFP-YFP pair remains widely used due to favorable spectral overlap, with derivatives such as ECFP and YPet showing improved sensitivity for single-cell imaging [24]. Alternative pairs including mCerulean/YPet and cpTFP1/cpVenus offer varying dynamic ranges and spectral characteristics suitable for different experimental needs [28]. Lanthanide-based FRET (LRET) with Tb(III) complexes as donors provides exceptionally long excited-state lifetimes (~milliseconds), enabling time-gated detection that eliminates short-lived background fluorescence and significantly enhances signal-to-background ratios [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Representative FRET Biosensors

| Biosensor | FRET Pair | Target | Dynamic Range | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rac1 LRET Sensor | Tb(III)/EGFP | Rac1 GTPase activity | Up to 1100% | 30 nm ER/K linker; time-gated detection [28] | Cell-based screening in 96-well plates [28] |

| Rac1-2G | cpTFP1/cpVenus | Rac1 GTPase activity | ~70% | Circularly permuted FPs; optimized linkers [28] | Live-cell imaging of membrane dynamics [28] |

| qMaLioffG | Single FP FLIM | ATP | 1.1 ns lifetime change | Fluorescence lifetime-based; 488 nm laser compatible [1] | Quantitative ATP imaging in cytoplasm and mitochondria [29] [1] |

| Kinase Biosensors | CFP-YFP variants | Various kinases | 50-150% | Conformational change upon phosphorylation [27] [24] | Monitoring signaling dynamics in live cells [27] |

| MaLionG | Citrine-based | ATP | 390% ΔF/F₀ | Intensity-based turn-on sensor [1] | ATP monitoring with high intensity change [1] |

Experimental Validation and Calibration Approaches

Robust calibration methodologies are essential for ensuring quantitative accuracy in FRET measurements, particularly for comparing results across different experimental sessions and instrumentation. A significant challenge in conventional FRET imaging is the sensitivity of the FRET ratio (acceptor-to-donor signal ratio) to imaging parameters such as laser intensity, detector sensitivity, and optical path variations [27]. Recent innovations address this limitation through the incorporation of calibration standards into experimental designs.

The barcoded calibration approach introduces engineered "FRET-ON" and "FRET-OFF" standards into subsets of cells, enabling normalization of fluorescence signals against these reference points [27]. Theoretical modeling and experimental validation have demonstrated that including both high- and low-FRET standards, along with donor-only and acceptor-only controls, allows for precise determination of actual FRET efficiency independent of imaging conditions [27]. This calibration strategy restores expected reciprocal changes in donor and acceptor signals that are often obscured by imaging fluctuations and photobleaching, facilitating reliable cross-experimental comparisons and long-term studies [27].

For FLIM-FRET applications, quantitative imaging relies on establishing calibration curves that correlate fluorescence lifetime with analyte concentration. In the case of the qMaLioffG ATP sensor, researchers created calibration curves in membrane-permeabilized cells, demonstrating slight differences compared to solution-based measurements but providing crucial reference data for interpreting intracellular ATP concentrations [1]. These calibration approaches are particularly important for applications requiring precise quantification, such as monitoring metabolic changes in disease models or evaluating drug effects on cellular energy states [29] [1].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

FLIM-FRET Protocol for Quantitative ATP Imaging

The qMaLioffG system represents a cutting-edge approach for quantitative ATP monitoring using FLIM-FRET methodology [29] [1]. Below is a detailed experimental protocol:

Sensor Expression and Sample Preparation:

- Construct Design: The qMaLioffG indicator employs a single green fluorescent protein scaffold with an inserted ε subunit of a bacterial FoF1-ATP synthase ATP-binding domain, optimized with specific peptide linkers to enhance transmission of ATP-induced conformational changes [1]. The sensor exhibits a substantial fluorescence lifetime shift (1.1 ns) within physiologically relevant ATP concentrations (Kₓ of 2.0 mM at room temperature and 11.4 mM at 37°C) [1].

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Culture appropriate cell lines (e.g., HeLa cells, human skin fibroblasts, mouse embryonic stem cells) under standard conditions. Transfect with qMaLioffG expression vector using preferred transfection method; generate stable cell lines for consistent expression [1].

- Sample Preparation for Validation: For 2D cultures, plate cells on glass-bottom dishes 24-48 hours before imaging. For 3D systems, prepare HeLa cell spheroids or tissue samples such as Drosophila brain [1].

FLIM Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Microscope Setup: Utilize a fluorescence lifetime imaging microscope equipped with a 488 nm laser source, pulsed laser system, and time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) detection capabilities [1].

- Image Acquisition Parameters: Set optimized laser power to minimize photobleaching and phototoxicity during time-lapse experiments (typically 1-hour duration). Maintain consistent temperature (37°C with CO₂ supplementation for live cells) [1].

- Lifetime Calculation: Acquire fluorescence decay curves for each pixel. Fit decay profiles to appropriate models (e.g., multi-exponential decay) to calculate fluorescence lifetime values [29] [1].

- ATP Concentration Calibration: Generate a calibration curve by measuring fluorescence lifetime in membrane-permeabilized cells with controlled ATP concentrations. Use this curve to convert experimental lifetime values to absolute ATP concentrations [1].

Validation and Perturbation Experiments:

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Apply metabolic inhibitors to validate sensor responsiveness. Use sodium fluoride (NaF, 10-50 mM) to inhibit glycolysis and oligomycin (1-5 µM) to inhibit oxidative phosphorylation. Monitor ATP depletion in cytoplasm and mitochondria [1].

- Disease Modeling: Compare ATP levels in normal versus diseased cells (e.g., fibroblasts with DNM1L mutations causing mitochondrial dysfunction) to reveal pathological metabolic alterations [1].

- Data Analysis: Quantify ATP concentrations in different cellular compartments (cytoplasm vs. mitochondria). Perform statistical comparisons between experimental conditions using appropriate tests [1].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for quantitative ATP imaging using qMaLioffG FLIM-FRET

LRET Biosensor Protocol for Rac1 Activity Screening

This protocol details the implementation of LRET biosensors with ER/K linkers for quantitative analysis of Rac1 GTPase activity in cell lysates, suitable for 96-well plate screening applications [28]:

Biosensor Design and Expression:

- Construct Assembly: Design the biosensor with domain order: (N- to C-terminus) EGFP (acceptor), Rac1 binding domain (PBD, residues 68-150), ER/K linker (10, 20, or 30 nm length), eDHFR domain, and full-length Rac1. The extended helical linkers ensure proper separation in the inactive state [28].

- Vector Preparation: Clone the construct into appropriate mammalian expression vectors. Include control constructs with flexible linkers for performance comparison [28].

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Culture HEK293T or other suitable cells. Transfect with biosensor construct using polyethyleneimine (PEI) or similar transfection reagent. Harvest cells 48 hours post-transfection [28].

Lysate Preparation and LRET Measurement:

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse cells in appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1% Triton X-100, plus protease inhibitors). Clarify lysates by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C [28].

- Tb(III) Complex Labeling: Incubate cell lysates with TMP-Tb(III) conjugate (100-500 nM final concentration) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature to allow specific binding to the eDHFR domain [28].

- Time-Gated Luminescence Measurement: Transfer samples to black 96-well plates. Use a plate reader with time-gated detection capabilities: set delay time = 0.1 ms, gate time = 0.2-0.5 ms, excitation = 340 nm, emission = 520 nm (Tb donor) and 515 nm (EGFP acceptor) [28].

- LRET Ratio Calculation: Calculate the LRET ratio as the acceptor emission (515 nm) divided by the donor emission (520 nm). Normalize values to donor-only controls [28].

Rac1 Modulation and Validation:

- Rac1 Activation: Treat lysates with GTPγS (100 µM) in the presence of EDTA (10 mM) to maximally activate Rac1. Include control samples with GDP (100 µM) to maintain inactive state [28].

- Inhibitor Screening: Test Rac1 inhibitors (e.g., NSC23766) at varying concentrations (0.1-100 µM) to demonstrate dose-responsive changes in LRET signal [28].

- Data Analysis: Calculate Z' factors to assess assay quality for high-throughput screening. Determine dynamic range as: [(LRET ratioactive - LRET ratioinactive)/LRET ratio_inactive] × 100% [28].

Figure 2: LRET biosensor workflow for Rac1 activity screening

Research Reagent Solutions for FRET Biosensing

The successful implementation of FRET-based quantification requires specific research reagents and materials optimized for various experimental scenarios. The following table details essential solutions for different FRET applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FRET Biosensor Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins | CFP/YFP pairs [24], cpTFP1/cpVenus [28], ECFP/YPet [24] | Donor-acceptor pairs for genetically encoded FRET biosensors | Spectral overlap, quantum yield, maturation efficiency, photostability [24] [28] |

| Lanthanide Complexes | Tb(III) complexes with TMP conjugates [28] | LRET donors for time-gated detection | Long excited-state lifetime (~ms); enables background-free detection [28] |

| Specialized Linkers | ER/K helical linkers [26] [28] | Spatial separation of biosensor domains | Rigid α-helical structure; tunable length (10-30 nm); enhances dynamic range [28] |

| Sensing Domains | Pak1 PBD (Rac1 binding) [28], ε subunit of FoF1-ATP synthase (ATP binding) [1] | Target recognition elements | Specific binding affinity; conformational change upon ligand interaction [1] [28] |

| Calibration Standards | FRET-ON and FRET-OFF constructs [27], donor-only and acceptor-only controls [27] | Signal normalization and quantification | Reference values for FRET efficiency; enables cross-experiment comparison [27] |

| Metabolic Modulators | Sodium fluoride (glycolysis inhibitor) [1], oligomycin (OXPHOS inhibitor) [1] | Perturbation agents for validation | Induce controlled changes in metabolic parameters [1] |

Emerging Applications and Future Perspectives

Advanced Applications in Biomedicine

FRET biosensing technologies continue to expand into increasingly sophisticated biomedical applications. In immuno-oncology, FLIM-FRET has emerged as a powerful approach for quantifying immune checkpoint interactions, particularly the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, providing superior predictive value for immunotherapy response compared to traditional immunohistochemistry [22]. This application leverages the ability of FRET to directly measure molecular interactions rather than mere co-localization, offering functional insights into immune cell-tumor cell interactions within the tumor microenvironment [22].

In mechanobiology, FRET biosensors enable real-time monitoring of cellular mechanical forces and their transduction into biochemical signals. These applications reveal how cells sense and respond to biomechanical properties of their extracellular matrix, with implications for understanding fibrosis, atherosclerosis, and cancer progression [24]. The development of genetically encoded tension sensors (GETS) based on FRET pairs has enabled precise measurement of molecular-scale forces in living systems, opening new avenues for investigating mechanopharmacological interventions [26].

The integration of FRET with super-resolution microscopy techniques has further expanded its applications to nanoscale cellular organization, while combinations with other spectroscopic methods like FCS (Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy) enable comprehensive analysis of molecular dynamics across spatial and temporal scales [25] [26]. These advanced applications demonstrate how FRET biosensing continues to evolve beyond traditional boundaries, providing increasingly refined tools for quantitative biological research.

Technological Innovations and Future Directions

The future of FRET biosensing is marked by several promising technological trajectories. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with FRET data analysis is enhancing the precision and throughput of biosensor calibration and quantification [23] [27]. AI-assisted approaches facilitate automated identification of FRET efficiency patterns and enable more sophisticated analysis of complex multiparameter FRET data [23].

The development of novel fluorophore pairs with improved spectral characteristics, reduced photobleaching, and enhanced brightness continues to address current limitations in FRET biosensing [26]. Particularly valuable are far-red and near-infrared FRET pairs that minimize autofluorescence and enable deeper tissue imaging, expanding applications to in vivo and clinical settings [26].

The incorporation of advanced nanomaterials such as quantum dots, upconverting nanoparticles, and conjugated polymers as FRET donors or acceptors offers enhanced photostability, tunable spectral properties, and improved signal amplification [23] [26]. These materials potentially address limitations associated with traditional fluorescent proteins, including limited brightness and susceptibility to photobleaching [23].

Miniaturization and multiplexing represent another frontier, with developments in biosensor barcoding enabling simultaneous monitoring of multiple analytes or activities in the same cell [27] [26]. This approach, combined with microfluidic platforms, supports high-content screening applications for drug discovery and systems biology research [27] [26]. As these technological innovations mature, FRET biosensing is poised to deliver increasingly powerful capabilities for quantitative analysis of protein interactions and microenvironmental parameters in complex biological systems.

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) has emerged as a transformative quantitative technique in biological research, enabling scientists to probe cellular environments, protein interactions, and metabolic states with exceptional precision. Unlike fluorescence intensity measurements, which are susceptible to variations in probe concentration, excitation light intensity, and optical path length, fluorescence lifetime provides an inherent molecular property that is largely independent of these factors, making it particularly valuable for quantitative cellular imaging [29] [31]. The lifetime (τ) of a fluorophore represents the average time a molecule remains in its excited state before returning to the ground state by emitting a photon, typically occurring on the nanosecond timescale.

The accurate interpretation of FLIM data hinges on selecting appropriate decay models and lifetime calculation methods. Fluorescence decay profiles generally fall into two primary categories: single-exponential decay, characterized by a uniform population of fluorophores in identical environments, and multi-exponential decay, which arises from multiple distinct fluorescent species or a single fluorophore population experiencing different microenvironments [32]. The choice between these models carries significant implications for quantitative biological applications, including the accurate determination of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) efficiency, quantification of metabolite concentrations, and assessment of dynamic quenching behaviors. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these fundamental approaches, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols relevant to research scientists and drug development professionals engaged in validating FLIM for quantitative measurement research.

Single vs. Multi-Exponential Decay Models

Mathematical Foundations and Theoretical Background

The mathematical description of fluorescence decay begins with the fundamental principle of exponential decay. A single-exponential decay model represents the simplest case, where the fluorescence intensity I(t) at time t after instantaneous excitation is described by the equation:

I(t) = I₀e^(-t/τ)

where I₀ is the initial intensity at t=0, and τ is the fluorescence lifetime. This model implies a single, homogeneous population of fluorophores where de-excitation occurs through first-order kinetics with a single characteristic lifetime [33] [32]. In practice, the single-exponential model is most applicable to purified fluorophores in homogeneous solutions where all molecules experience identical environmental conditions.

In contrast, biological systems frequently exhibit multi-exponential decay behavior due to molecular heterogeneity. The multi-exponential model is described by:

I(t) = I₀∑qᵢe^(-t/τᵢ)

where qᵢ and τᵢ represent the amplitude fraction and lifetime of the i-th component, respectively, with the constraint that ∑qᵢ = 1 [34]. This complex decay profile arises from several biological scenarios: multiple fluorophore species with distinct lifetimes, a single fluorophore species existing in different conformational states, environmental heterogeneity around fluorophores (e.g., varying pH, viscosity, or ion concentrations), or FRET processes where only a fraction of donor molecules interact with acceptors [35] [36]. For fluorescent proteins and biological samples specifically, multi-exponential decays are "the norm rather than the exception" [35].

Comparative Analysis of Model Characteristics

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Single vs. Multi-Exponential Decay Models

| Feature | Single-Exponential Decay | Multi-Exponential Decay |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | I(t) = I₀e^(-t/τ) | I(t) = I₀∑qᵢe^(-t/τᵢ) |

| Number of Parameters | 2 (I₀, τ) | 2p (I₀, q₁...qₚ, τ₁...τₚ) |

| Photophysical Interpretation | Single uniform fluorophore population | Multiple distinct populations or environments |

| Common Applications | Purified dyes in solution, simple systems | Biological samples, FRET, fluorescent proteins, complex environments |

| Data Requirements | Lower photon counts sufficient | High photon counts required for reliable fitting |

| Computational Complexity | Low | High, increases with number of components |

| Common in Biological Imaging? | Rare | Very common |

The choice between these models carries significant implications for quantitative biological applications. Multi-exponential analysis provides more detailed information about molecular heterogeneity but requires higher data quality and more complex computational approaches. As noted in research on FLIM limitations, "the availability of detailed decay functions is critical for multi-exponential FLIM analysis" [36], with advanced time-correlated single-photon counting systems and maximum-likelihood estimation techniques improving the feasibility of resolving multiple exponential components.

Impact on Biological Interpretation

The distinction between single and multi-exponential decay models profoundly affects biological interpretation of FLIM data. For instance, in FRET experiments, a double-exponential decay often indicates that only a fraction of donor molecules participates in energy transfer, while the remainder exists in a non-interacting state [36]. Treating such a system with a single-exponential model obscures this heterogeneity and can lead to inaccurate FRET efficiency calculations. Similarly, in metabolic imaging using autofluorescence from NAD(P)H and FAD, multi-exponential analysis can resolve protein-bound and free populations of these cofactors, providing insights into cellular metabolic states that would be lost with single-exponential fitting [9].

Recent advances in FLIM-compatible biosensors further highlight the importance of appropriate decay modeling. The development of qMaLioffG, a genetically encoded ATP indicator, demonstrates how fluorescence lifetime changes can enable quantitative metabolite imaging [29] [1]. Given the complex intracellular environment, such sensors often exhibit multi-exponential behavior that must be properly characterized for accurate concentration measurements.

Mean Lifetime Calculations in Quantitative FLIM

Amplitude-Weighted vs. Intensity-Weighted Average Lifetimes

For multi-exponential decays, researchers often calculate average lifetimes to simplify data interpretation and comparison. The two most prevalent averaging methods—amplitude-weighted and intensity-weighted—serve distinct purposes in quantitative FLIM and yield different values for the same decay profile.

The amplitude-weighted average lifetime (τₐ or ⟨τ⟩ₐₘₚ) is calculated as:

τₐ = ∑qᵢτᵢ

where qᵢ are the normalized amplitude components (∑qᵢ = 1) and τᵢ are the individual lifetime components [32] [34]. This parameter weights each lifetime component by its relative amplitude proportion, making it particularly valuable for FRET efficiency calculations and dynamic quenching studies according to the Stern-Volmer relationship [34].

The intensity-weighted average lifetime (τᵢ or ⟨τ⟩ᵢₙₜ) is defined as:

τᵢ = ∑(qᵢτᵢ²) / ∑(qᵢτᵢ)